A possible explanation for the mysterious ice circles in Lake Baikal

A team of researchers affiliated with several institutions in Russia and one in France has found a possible explanation for the creation of ice circles in Lake Baikal—the deepest lake in the world. In their paper published in the journal Limnology and Oceanography, the group describes their two-year study of the ice circles and what they learned about them.

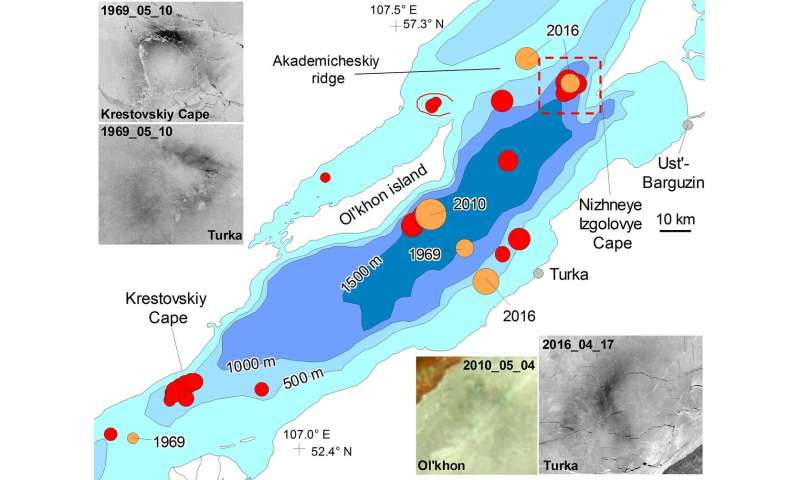

Approximately twenty years ago, scientists became aware of ice circles forming in different locations in Lake Baikal in the spring and summer months. The mysterious circles were so large that they could only be seen from airplanes or satellites. The initial suspicion was that they formed due to methane bubbling up from below. But testing showed no methane deposits below the lake.

The lake is located in Siberia, where it gets so cold that its surface freezes over completely during the winter months. The ice circles that have been observed have appeared in different sizes and different locations—but they are all characterized by a bright center surrounded by a dark circle. Prior research had shown them to be on average 5 to 7 kilometers in diameter. They also last from just a few days to a few months. Additional research showed that the ice rings were not exclusive to Lake Baikal—some were seen in Mongolia, in Lake Hovsgol and another in Russia's Lake Teletskoye. Such sightings suggested they likely appear in most deep lakes that freeze over during the winter. But there was still no explanation for how they formed.

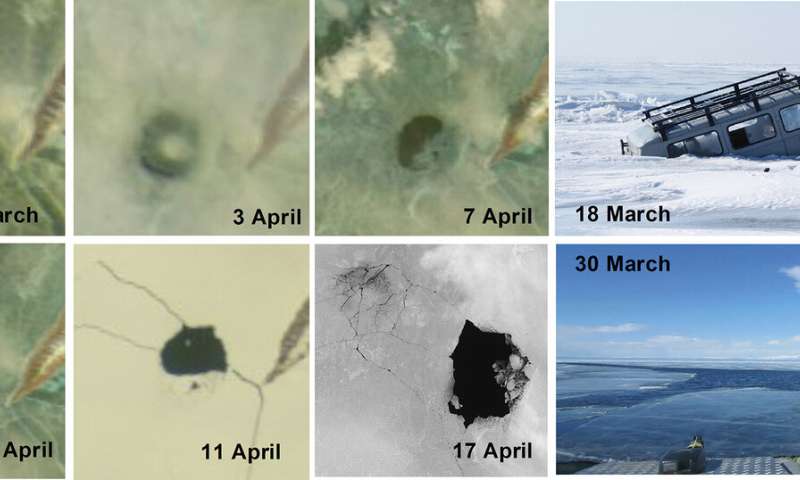

Determined to find the answer, the researchers with this new effort traveled to the lake several times over the winters of 2016 and 2017. On each expedition, the drilled holes in the ice and dropped sensors into the lake where the circles were forming. They also studied infrared satellite images that revealed temperature variations in the lake. In February of 2016, the team found a possible clue—an eddy had formed in the water beneath the ice circle. And the water in the eddy was a couple of degrees warmer than the water around it. The researchers suggest the ice circles are formed due to water movement and temperature differences from surrounding water due to eddy formation. The following year the team found another eddy, this one without a circle above it. They suggested that they had spotted the eddy before a circle formed above it. They were not able to explain why the eddies were forming, however.

More information: Alexei V. Kouraev et al. Giant ice rings on lakes and field observations of lens‐like eddies in the Middle Baikal (2016–2017), Limnology and Oceanography (2019). DOI: 10.1002/lno.11338

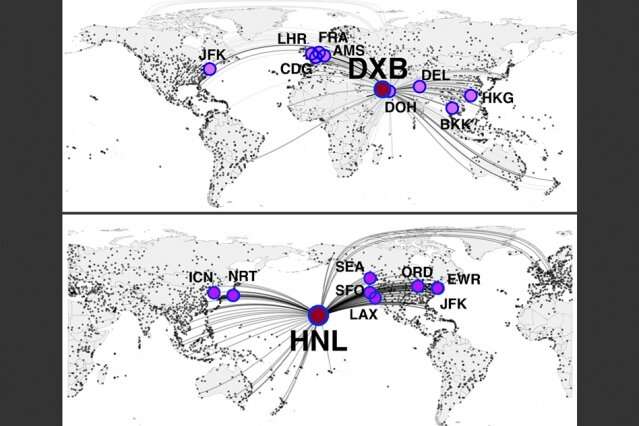

Based on their study, the authors found that focusing efforts to increase handwashing rates at just 10 airports chosen based on the location of the outbreak could significantly reduce disease spread. In these maps, they show the airports that would be targeted for outbreaks originating near Honolulu, Hawaii, or Dubai, United Arab Emirates. Credit: Massachusetts Institute of Technology

Based on their study, the authors found that focusing efforts to increase handwashing rates at just 10 airports chosen based on the location of the outbreak could significantly reduce disease spread. In these maps, they show the airports that would be targeted for outbreaks originating near Honolulu, Hawaii, or Dubai, United Arab Emirates. Credit: Massachusetts Institute of Technology