PETITE BOURGEOIS MORALITY

FROM THE ROKEBY VENUS TO FASCISM

PT 1: WHY DID SUFFRAGETTES ATTACK ARTWORKS?

THE ATTACK ON THE ROKEBY VENUS

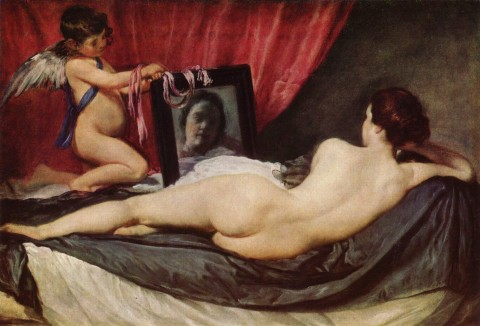

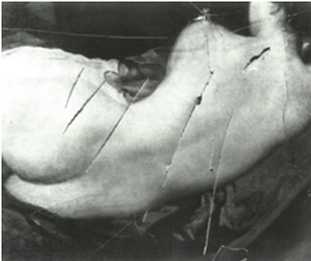

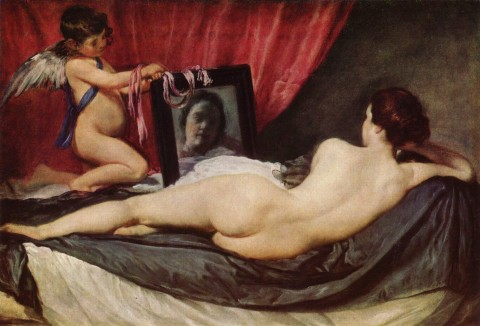

Just on 100 years ago, a small soberly-dressed woman carrying a sketch book entered the National Gallery in London and physically attacked one of the most famous nude paintings in the world (Fig 1).

Fig 1: Diego Velásquez, Venus at her Mirror (1647-51)

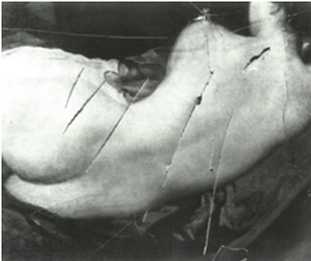

It was just after 10 o’clock on the morning of 10 March 1914 [1]. The painting, Velásquez’s so-called “Rokeby Venus” [2], was standing on an easel in Room 17, temptingly accessible. The woman stepped forward, took a narrow meat chopper which had been concealed up her sleeve and began swinging, getting in what she later described as several “lovely shots”, smashing the protective glass and making numerous large slashes in the painted canvas (Fig 3). The room attendant’s initial belief that the breaking glass was coming from a skylight gave the woman precious time to carry out the attack, and the delay in stopping her was compounded by the attendant slipping on the recently-polished floor when running to intervene. However, the attacker was eventually restrained, and arrested. On the next day, now identified as the well-known militant suffragette Mary Richardson (Fig 2), she was convicted on charges of malicious damage, and sentenced to the maximum penalty of six months imprisonment.

Fig 2: Mary Richardson

|

Fig 3: The slashed canvas

|

After Richardson’s arrest, she explained her actions on the basis that, “I have tried to destroy the picture of the most beautiful woman in mythological history as a protest against the Government destroying Mrs Pankhurst, who is the most beautiful character in modern history. Justice is an element of beauty as much as colour and outline on canvas” [3]. “Mrs Pankhurst” was Emmeline Pankhurst, the campaigner for women’s voting rights and leader of the militant Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU), who had been arrested in extraordinarily violent circumstances the day before. Richardson’s view was that if people were outraged about her own attack on the painting, which was a mere representation of physical beauty, they should be equally or more outraged over the government’s treatment of Pankhurst, a real embodiment of moral beauty.

Richardson insisted that as a student of art herself it had been difficult for her to damage such a beautiful work, but that her hand had been forced by the government’s indifference to the suffragist cause [4]. She also added “You can get another picture, but you cannot get a life, as they are killing Mrs Pankhurst" [5]. In her autobiography [6], Richardson also said that the high financial value of the painting made it a suitable surrogate for the high value of Mrs Pankhurst. A less elevated consideration emerged in an interview Richardson gave some decades later: “I didn’t like the way men visitors to the gallery gaped at it all day” [7].

“A BODY FOR DON JUANESQUE FANTASIES”

In many ways the Rokeby Venus was an ideal target for suffragette attack. As the commentators Rose-Marie and Rainer Hagen say, it was originally painted to display “a body for Don Juanesque fantasies” in a country (Spain) in which extreme machismo was the hallmark and women were regarded as “inferior, voiceless and … easy prey”. They add that “few other paintings celebrate, so aesthetically and alluringly, the reduction of Woman to a physical body, to the object of male desire. Venus's face, which might reveal something of her individuality and mind, is blurred in the mirror, while her curving pelvis is placed in the centre of the composition. The dark sheet sets off Venus's skin to particular advantage and is almost like a dish on which the beautiful goddess is presented” [8].

Although being regarded as the first known painting of a nude by a Spanish artist [8A] – the next one would not be until Goya's Naked Maja more than a century later – the Venus escaped censure from the Inquisition only by the fact that it was nominally of a mythological subject, and had been painted under the personal protection of the licentious Spanish King Philip IV. All in all, then, the idea of attacking it could well seem attractive to a fighter for women's rights. As an added bonus, attacking the painting would enable Richardson to come as near as possible to blood-shedding without actually infringing the suffragettes’ policy of not endangering human life [9].

READ ON

BRITISH ARYANISM BECOMES POLICING

FROM THE ROKEBY VENUS TO FASCISM

PART 2: THE STRANGE ALLURE OF FASCISM

By Philip McCouat

THE PATH TO A "GREATER BRITAIN"?

After the war, Mary Richardson, the hero/villain of the Rokeby Venus attack, adopted a son and settled in Cambridgeshire to raise ducks with a friend, and to pursue her literary career. It is difficult to imagine a more striking contrast with her earlier life of high excitement. Evidently, however, she still hankered for a public platform. She stood for Parliament a number of times, though with little success [49], and it must have seemed that her action days might be behind her. She was, however moving rapidly to the Right. In 1933, after previously flirting with the New Party in 1932, she joined the charismatic Oswald Mosley's recently- formed British Union of Fascists (BUF).

---------------------------------------

For Part 1 of this article, see here. and for other articles on art and war, see:

The Isenheim Altarpiece Pt 2: Nationalism, Nazism and DegeneracyThe Isenheim Altarpiece Pt 2: nationalism, nazism and degeneracy

Bellotto and the reconstruction of Warsaw

The shocking birth and amazing career of Guernica

------------------------------------------------

She quickly rose up through the BUF’s ranks. By 1934, she was Chief Organiser of the Women’s Section of the party, a highly prestigious and responsible position that had originally been held by Mosley's wife Cynthia. She opened a national Club for Fascist Women in London, spoke at BUF branch meetings, was a fiery chief speaker at outdoor and street corner meetings, wrote regularly for the Fascist press, and even organised the quaintly-named Blackshirt Cabaret Ball.

She said that she saw Fascism as the “only path to a 'Greater Britain'” and that she felt “certain that women will play a large part in establishing Fascism in this country” [50]. However, despite these high initial hopes, she ultimately left the BUF in 1935/6 for reasons that are disputed, but seem to have involved her having organised a meeting protesting against the unequal remuneration of women employed by the movement [51].

You may wonder why a person such as Richardson, who had dedicated and sacrificed herself to the cause of gaining the vote, would have joined an organisation which favoured an undemocratic, totalitarian government with ultimate power vested in a supreme leader. However, Richardson herself claimed that there was a logical continuity with her militant suffragette activities: “I was first attracted to the Blackshirts because I saw in them the courage, the action, the loyalty, the gift of service and the ability to serve which I had known in the suffragette movement. When I later discovered that Blackshirts were attacked for no visible cause or reason I admired them the more when they hit back and hit back hard” [52].

For Richardson, it was similar to the overwhelming almost-religious conversion she had experienced years earlier when she heard Mrs Pankhurst speak. She later recalled that at her first meeting with the BUF leader Mosley, “I cannot remember a single word of what was said on that momentous occasion. But the words did not matter. In some strange way I was inspired by the atmosphere of that great gathering. ‘We will fight’, I kept on repeating to myself”[53].

THE OTHER SUFFRAGETTE FASCISTS

Of course, the vast majority of ex-suffragettes did not embrace Fascism as Richardson did. Many, such as Sylvia Pankhurst, actively opposed it. But in addition to Richardson there were two other notable ex-suffragettes that later went on to prominent positions in the Fascist movement. They were Norah Elam [54] and Mary Sophia Allen [55]. The careers of both of these women are instructive in considering the motives, or claimed motives, of the various types of person that Fascism attracted.

For Allen, Mrs Pankhurst's closure of the militant campaign on the outbreak of war came as a “bewildering blow”. “I won’t pretend that we like it!” she wrote later. At the time, she said, she was “actively – and shall I admit it, delightedly – planning some further burnings of empty houses, in which we had been so successful of late” [67]. The change of focus left her bereft of adventurous ways of serving her country. Hardly surprisingly, she scorned the offer of a job as organiser for Queen Mary’s Needlework Guild (!), and along with a number of other suffragette women she joined the first Women Police Service (WPS) – a somewhat ironic choice, given her criminal record and history of resisting police. She became second-in-command to Margaret Dawson – who became her partner – and some years later took over as Commandant after Margaret died [68].

READ ON http://www.artinsociety.com/from-the-rokeby-venus-to-fascism-pt-2-the-strange-allure-of-fascism.html