Political Cynicism and the Polish Presidential Elections

THE POLES WENT TO THE POLLS THIS WEEKEND

HERE IS A BACKGROUNDER

Following surprising increases in voter turnout in 2019, sociologists Przemysław Sadura and Sławomir Sierakowski conducted research on the attitudes of the rural and semi-rural voters in Poland. Their findings reveal that voters remain rational actors with a good grasp of politics but that cynicism permeates their choices and perspectives. Ahead of the now postponed presidential elections, that were controversially set to go ahead this May despite the COVID-19 pandemic, Przemysław Sadura asks where next for the opposition.

Politics has always been a dirty business. Even the most idealistic and well-briefed ministers and MPs lied, cheated, took bribes, or stole. When caught, they committed suicide, retired, went into temporary hiding, or solemnly repented for their sins. They may have been seen as hypocrites, but their stances never put the meta-rules of the democratic system into question. The voters would simply put their faith in different politicians at the next elections. But what happens when the situation repeats itself again and again? What happens when even the elites give up on meeting the expectations of citizens?

According to critical philosophers such as Peter Sloterdijk and Slavoj Žižek, democratic ideology turns into political cynicism in such a scenario. The cynical subject is aware of the distance between the ideological mask and social reality, but, nonetheless, insists upon the mask. It is well expressed by Sloterdijk’s formula: “They know very well what they are doing, but still, they are doing it”. Cynical reason is no longer naïve or hypocritical but is a paradox of an enlightened false consciousness: one knows the falsehood very well, one is well aware of a particular interest hidden behind an ideological universality, but still one does not renounce it.

It can be neatly summed up by an anecdote on political honesty that I heard years ago from a former minister from the post-Solidarity camp:

“First, you have people that are personally honest and do not take anything for themselves or their party. The second level of honesty is when a person is completely honest but says that a “big haul” is necessary to pay for political work, and that everything will be done honestly afterwards. The third level consists of people who take part of the money for themselves. The fourth level… well, these are crooks that go into politics just to make money.”

My interlocutor declared himself as a proponent of the second option and argued that the worst people for any party are the total crooks and the radical idealists (sic!). Of course, he was so candid under the condition of anonymity. Today, cynicism among mainstream politicians is common. It is not at all shocking for large parts of the electorate. Trump, Johnson, Salvini, Kaczyński, Orbán, and Bolsanaro – each of them could credibly rebut the accusation of lying with the claim: “I never promised to be honest, just effective.” Their brazenness resembles that of the janitor in the often referenced 1980 cult film Miś (Teddy Bear). When challenged by a client whose coat has gone missing, the janitor stares right into his eyes and replies: “I don’t have your coat – whatcha gonna do about it?”

Cynical voters?

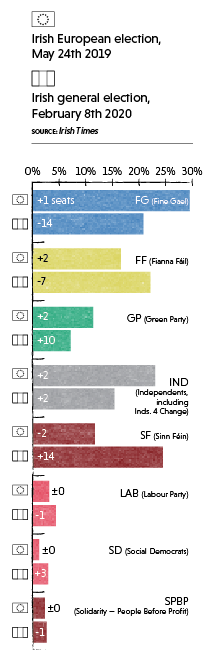

What is the source of such a stance and how does the electorate respond? Years of research on Polish voters have revealed a certain paradox. The less favourable opinion Poles have about politics, the more politically engaged they become. It is most easily observed in the rise of the turnout during elections. Turnout in Poland has climbed from one of the lowest in Europe to a more average level compared to elsewhere in the EU. Turnouts between 20-24 per cent in European elections in the first decade of the 2000s rose to 45 per cent in 2019. Turnouts in national parliamentary elections rose from between 40-50 per cent in earlier years to almost 62 per cent in 2019.

Politics is a reality show. Updates on new swindles do not influence their views but are part of the spectacle like boxers insulting each other before a fight.

Focus group participants tend to explode when asked about their associations with politics. But, at the same time, year after year their language regarding politics became less engaged. They see politics akin mud wrestling, something to be actively observed but not to get drawn into. They have their favourite candidates and, as if watching football, they identify with their team. However, when asked if they ever would join a political party, they treat it as a personal insult. Politics is a reality show. Updates on new swindles do not influence their views but are part of the spectacle like boxers insulting each other before a fight. Someone offered a bribe? Great, the show will be even better!

A long, long time ago, when the Earth was still inhabited by neoliberal dinosaurs, there was a theory called “trickle-down economics”. It argued that economic and fiscal policies that help the richest in society make poorer people better off too. The welfare of the rich would trickle down to the poor. The metaphor did not turn out well in economics, but it may still have some potential in describing political processes. Cynicism that was first limited to politicians has spilled over to voters. Some voters became disenchanted and began to treat politics in a similar way to the politicians, thinking, unapologetically, about ways to “play” and win.

Sławomir Sierakowski and I encountered such voters in focus groups organised in the run-up to the 2019 Polish parliamentary elections. Our report, Political Cynicism: The Case of Poland, was widely discussed by Polish media ahead of the election that saw the Law and Justice Party (PiS) retain its majority in the Sejm lower house but lose its majority in the Senate. Ahead of the presidential election now postponed from May to some point in the summer, it is time to reconsider those election results from the point of view of our findings.

The case of Poland

Our conversations with voters showed that growing part of the electorate has a cynical view of politicians. Their vices and pathological behaviour are plain to see but are deemed acceptable as long as the supported party is working for their interests. The PiS voters are willing to turn a blind eye towards corruption and political scandals. Before the 2019 election, the head of the audit office nominated by PiS was found to have links to organised crime. But PiS voters overlook such matters in exchange for social transfers and official disdain towards an urban elite seen as hostile to “the people”. Sympathisers of the opposition, led by the Civic Platform (PO), are also able to ignore cases of individual corruption and unethical behaviour in exchange for dynamic economic growth and private freedoms. Casting a vote is less a proof of trust towards politicians from the preferred side and more a reflection of hostility towards the other side’s party machinery and voters. Such polarisation drives the paradox mentioned above: the worse the opinion of Poles regarding politics, the higher the turnout come election day.

What is interesting is that PiS voters did not want a constitutional majority for the party. They see a strong opposition as a positive force that guarantees that PiS will not shed its social policy credentials. They are not passive victims of state media propaganda – almost half of them consider Polish public radio and television to be biased. They are, in fact, more likely to state that they watch news from different broadcasters than PO voters, who tend to be more faithful to the private station TVN.

Casting a vote is less a proof of trust towards politicians from the preferred side and more a reflection of hostility towards the other side’s party machinery and voters.

Our research also shows that the voting blocs of different parties are by no means monolithic. PiS, along with its dominant group of loyal, conservative voters, now has a smaller (but still significant) group of new voters drawn to the party thanks to social transfers. In July 2019, more than a third of all voters declared that they would definitely vote for Jarosław Kaczyński’s PiS. A further 20 per cent stated that they would consider doing so. The numbers of potential voters observed were even larger in the case of the opposition blocs: Civic Coalition and the Left bloc. The main problem for the opposition was that the large overlap between their electorates meant fighting for the same votes. Such a phenomenon was noticed by the opposition voters themselves. They portrayed PO (the dominant force in the Civic Coalition [KO]) as an unlikeable yet strong “anti-PiS” party. When asked to draw a person that could represent the Left, focus group participants drew liberal PO’s younger brother.

Who won the 2019 elections?

Confronting our findings with election results prompts different conclusions than those of other analysts. 43.6 per cent for PiS was not a surprising or low result. The party gained both in terms of vote share (in 2015, it was 37 per cent) and the total number of votes (up by 2 million). Our July surveys showed the ceiling for PiS support was 55 per cent, of which 35 per cent was solid and a further 20 per cent that could be swayed.[1] PiS therefore mobilised almost half of its potential voters – much more than its competitors. The Left (with 8 per cent solid support and a ceiling of 20 per cent) managed 12.5 per cent, so just 4.5 percentage points out of a possible 12. KO only managed to convince a tenth of its potential voters.

The reactions of party leaders betray quite a different view of the elections. KO that, together with the rest of the opposition, barely won the elections in the Senate and yet was cheering as if it won the entire election. Similar euphoria could be spotted in the Left camp. The centre-right Polish Coalition (PSL) and far-right Confederacy, which had even smaller shares of the votes, were even more ecstatic. The only politicians that looked displeased were on the side of the ruling party. Why was not PiS satisfied with the election result? Was it because they had fallen for their own propaganda and were expecting a constitutional majority? Or maybe they were thinking that luck would come to their side once more? In 2015, a few parties did not pass the electoral threshold and Kaczyński obtained an outright majority in the Sejm with a 37.6 per cent score. This time, PiS needed 43.6 per cent to win basically the same number of seats.

Who lives by the sword…

Is the depression of the winners and the enthusiasm of the losers justified? Both seem premature. PiS gained a lower score than expected and lost control of the upper house in part due to the calculations of its electorate. Its voters, asked about a two-thirds constitutional majority for Jarosław Kaczyński, impulsively replied that they do not want such a scenario to occur. They said that they would feel better in a country in which the opposition can keep the government on its toes. In our research conducted just after the election, PiS voters confirmed that a check on PiS power was no bad thing.

PiS voters that turned to the party the past four years – less ideological and more oriented towards social transfers – had a key role in determining the final result. They may have their doubts over whether or not PiS will keep its long list of promises – especially if it dominates parliament. Poles want PiS rule, but do not want Orbán’s Budapest in Warsaw and did not want to give the party full control over events in Poland.

The future of the opposition and the opposition of the future

The opposition has two problems. The first one is finding an answer to the question of how to beat the incumbent in the upcoming presidential election. The second one is about using the four years until the next parliamentary election to regain PiS voters.

In terms of the first issue, there are few reasons for optimism. In our post-election interviews on possible presidential candidates, the verdict was clear. PiS voters are convinced that the re-election of Andrzej Duda will be swift – and most of the opposition seems to concur. Duda is seen by the media and engaged participants of anti-government demonstrations as subordinate to the will of Jarosław Kaczyński. But he is more commonly perceived as an independent statesman. The presidency confers a “halo effect”, in which the features of the presidency as an institution are transferred onto the person holding the office.

The Left needs to propose a social programme that can attract voters beyond urban elites. The liberal PO needs generational change at its helm to regain an energetic and efficient face.

For the opposition to reclaim parts of the PiS electorate, it should start by trying. Up until now PO and the Left have struggled over liberal voters. Only two parties pose a threat to PiS: PSL, very active in rural areas, and the far-right Confederacy. The Left is good at winning liberal voters in large cities but has no sway over the working classes in the countryside and smaller towns. Almost half of its electorate consists of people with a university degree, while the share of people with vocational education is three times larger in PiS than in the Left (25 compared to 8 per cent). This is a worse result even than the liberal PO. The Left is currently the most elitist formation in the Polish parliament. On a brighter note, it is also the freshest. If the Civic Platform continues to be largely inactive, the Left will be able to rise in the opinion polls, and – further down the road – also in parliamentary representation. But, without changes, the democratic bloc will not grow as a whole.

When, and provided, the presidential elections take place, it is likely that the opposition will lose and Poland will have three years without elections. If the opposition does not want to squander this time, three requirements need to be fulfilled. The Left needs to propose a social programme that can attract voters beyond urban elites. The liberal PO needs generational change at its helm to regain an energetic and efficient face. Both of these forces should play the cards PiS finds difficult to respond to. Decarbonisation may be one such topic. Poland under PiS rule seems to be at loggerheads with EU policy, stronger pressure from the European Union on this matter may also help the opposition.

FOOTNOTES

[1] Based on our survey, we estimated the current and potential size of the electorates of the three largest political camps in Poland. The core electorate of a given party consists of those who declare their intention to vote for that party in the upcoming elections. The potential electorate consists of those people who have not declared an intention to vote for the given party but have supported it in the past, or designate it as their second choice, while also expressing full or partial confidence in that party.