REVENANTS AND REVOLUTIONARIES: BODY AND SOCIETY IN ...

Bogdanov dreamed of a universal science of organization that would maximize the efficiency of all life systems, from the circulation of goods to the circulation of blood. His theory of organization, which he called tectology, guides the regulation of the body and society. Put into practice, tectology would maintain social and bodily equilibrium as humans evolve. Its creator …

It’s possible that I shall make an ass of myself. But in that case one can always get out of it with a little dialectic. I have, of course, so worded my proposition as to be right either way (K.Marx, Letter to F.Engels on the Indian Mutiny)

Friday, May 21, 2021

COMMIES ON MARS

Red Star - The First Bolshevik Utopia

by Alexander Bogdanov

Publication date 1913

Publisher Indiana University Press

Contributor Loren R. Graham and Richard Stites

Language English

Red Star - Engineer Menni - A Martian Stranded on Earth

Edited by: Loren R. Graham and Richard Stites

Translated by: Charles Rougle

Published by: Indiana University Press 1984

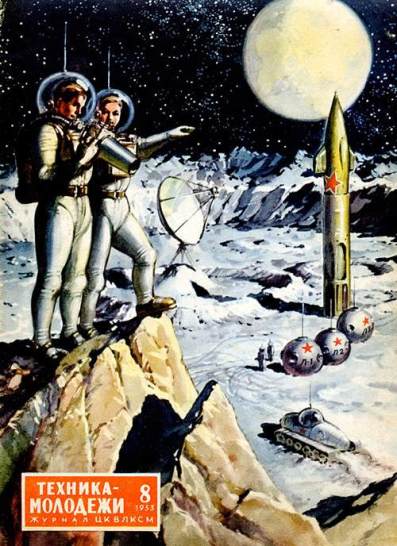

Still from Soviet sci-fi film, A Dream Come True (Mechte Navstrechu) (1963)

When brilliant Soviet cyberneticist Viktor Glushkov designed a blueprint for a computerised planning system, the Soviet Union looked on track to become web pioneers. In the end, however, there was to be no digital network. Justin Reynolds tells the story of how the Soviets nearly created the internet

7 February 2017

Visions of an advanced postcapitalist economy run by digital networks have long haunted the socialist imagination. Alexander Bogdanov’s 1909 Bolshevik sci-fi fantasy novel Red Star imagined the achievement of communist utopia on Mars, an abundance of wealth and leisure made possible by a sophisticated command economy planned and automated by prototype computers. Cerebral Martian engineers, their “delicate brains” connected to the machines through “subtle and invisible” threads, fine-tune economic inputs and outputs from a control room tracking production gluts and shortfalls.

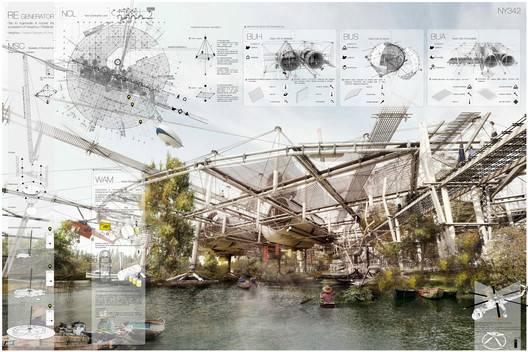

Bogdanov’s thought experiment anticipated contemporary speculations about the possibilities digital networks open for new forms of economic exchange. One current best-seller, Paul Mason’s Postcapitalism, suggests that the ease with which information can be shared online, together with the advent of 3D printing technologies, is seeding a new economy in which goods and services can be exchanged for free. Another, Nick Srnicek and Alex Williams’s Inventing the Future, envisages an automated economy set in motion by the seamless interactions of millions of connected devices.

Cybersyn control room, Chile. Image: Gui Bonsieppe under a CC license

Many of today’s digital utopians draw inspiration from a real world attempt to implement electronic socialism: Salvador Allende’s abortive 1970s programme that sought to rationalise and democratise the planning of the Chilean economy through a nationwide network of telex machines. “Project Cybersyn” was cut short by Pinochet’s coup, but, helped by the surviving images of its iconic retro-futurist central operations room, the episode continues to symbolise radical aspirations to harness technology to break through to an alternative economic system.

Cybersyn was conceived during the same era as a still more ambitious but less well documented project: a well-resourced programme to digitise the planning of the Soviet Union’s vast command economy. The labyrinthine story of the “Soviet internet” is told in detail in a new book by Tulsa University professor Benjamin Peters, who, venturing into Moscow archives “lit by a single flickering light bulb”, pieces together the tale of plans to supercharge the USSR’s stuttering economy through the installation and networking of a constellation of mainframe computers at major production points from Leningrad to Siberia. The project was one of the most spectacular manifestations of the restless Soviet ambition to lever technology to create the material conditions for “full communism”.

The 1970s was an era of harnessing technology to break through to an alternative economic system

From the beginning the USSR was intoxicated by an aesthetic of the machine. Lenin equated the achievement of socialism with the electrification of the nation. Planners sought to apply Fordist production techniques on an unprecedented scale. And avant-garde designers, architects and filmmakers insisted engineering was art, and art was engineering. But those visions far outran the technology available to the impoverished state. Stalin resorted to a forced march industrialisation programme that rammed Russia’s patchwork economy into a rigid pyramid structure, the output of factories and farms coordinated through targets set by regional authorities reporting to a central planning ministry.

This hulking machinery carried the USSR through successive five year plans achieved at the cost of monumental waste of human life and natural resources. Calculation errors caused chronic production shortfalls or overshoots that cascaded up and down the command chain and rolled on from year to year. By 1960, 3 million officials were attempting to track the economy’s unfathomable information flows, and it was forecast that if future growth targets were to be met, a bureaucracy equivalent to the entire working population would be required with 20 years.

Map of OGAS computer centres, 1964

To get things done, planners, managers and workers resorted to informal networks that criss-crossed official hierarchies. Far from being the rigid hierarchy of popular imagination, the Soviet economy relied on a vortex of informal ties and personal favours. But by the Khrushchev era, science seemed to be catching up with those early revolutionary dreams. Inspired by the new field of cybernetics — the study of information systems in nature, machines and human societies — Soviet economists began to reimagine the command economy as a reflexive system capable of recalibrating planning flows in response to new inputs. Emerging mainframe computing technologies would provide the number-crunching firepower to make it possible.

By the late 1950s a comprehensive blueprint for a computerised planning system had emerged: the All-State Automated System — known as the OGAS — designed by the brilliant cyberneticist Viktor Glushkov. Glushkov proposed overlaying a vast digital network on the economy’s pyramid structure: some 20,000 mainframes at major production points would be connected to hundreds of regional administrative centres pushing data to a central processing hub in Moscow.

By the late 1950s a comprehensive blueprint for a computerised planning system had emerged: the All-State Automated System — known as the OGAS

The OGAS anticipated cloud computing, allowing authorised workers, managers and administrators to input information to a central database accessible to all users, and looked ahead to today’s virtual currencies, proposing that physical money would be rendered redundant by the system’s capacity to process transactions using electronic receipts. The proposal was unashamedly utopian. Glushkov’s design aspired to the Marxist ideal of a rational economic system guided by worker inputs, and, like the engineers who led the Soviet space programme, he was captivated by the Russian cosmist desire for a kind of synthetic immortality. Rather like 21st century advocates of a “technological singularity”, Glushkov believed that, one day, ever more advanced networks would make it possible to upload personalities embedded in human neural circuits to a supercomputer.

The scale of the OGAS matched its philosophical grandeur: costing 20 billion rubles (today approximately $333.4 million) and requiring some 300,000 operators it would be rolled out over 30 years. And, in the beginning at least, it was an ambition the Soviet leadership shared. Glushkov was appointed head of a new Institute of Cybernetics, one of several well-funded research centres with a remit for digital innovation.

Viktor Glushkov speaking about management information systems. Image: ResearchGate

The project prospered during the Cold War high point of post-war Soviet technological optimism, the era of Sputnik and Gagarin. When rumours of Russian ambitions for rapid economic expansion reached an American government already concerned that Soviet space exploits signalled an emerging communist supremacy, the US redoubled efforts to build its own network, the ARPANET, the forerunner of today’s internet.

By 1970 Glushkov’s plan was ready to go before the Politburo for approval, which, with the promised backing of General Secretary Leonid Brezhnev and Premier Aleksei Kosygin, it seemed destined to secure. But it was not to be. Entering Stalin’s former office in the Kremlin to formally present his proposal, Glushkov noticed that Brezhnev and Kosygin’s chairs were empty. Their absence — ostensibly to attend state functions elsewhere — emboldened Finance Minister Vasily Garbuzov to force through a counterproposal that ripped the heart out of the plan. Permission was given to install computers at key production centres but not, crucially, for linking them together. The existing planning bureaucracy would be retained: there was to be no digital network. The OGAS, it seemed, whatever its promise, threatened too many vested interests.

In the end, there was to be no digital network as the OGAS, it seemed, threatened too many vested interests

After repeatedly failing over the following years to revive interest in his plan, the rational Glushkov began to succumb to conspiracy theories, suggesting interference by American spies, and that the emergency landing of a flight he had taken shortly after the Politburo meeting had been caused by sabotage. Glushkov died in 1982, by which time the Soviet leadership had pinned its hopes for economic renewal on limited market liberalisation, an approach that rendered the concept of a computerised command economy redundant.

In retrospect, the OGAS seems absurdly ambitious. The development of such a vast network would have necessitated a depth and duration of political commitment even an authoritarian regime could unlikely sustain, and it is doubtful that early mainframe technology would have been capable of processing so much data (quite apart from the vexed question of whether the very concept of a complex planned economy makes sense.) The OGAS could only have been conceived during an era when boundless faith in the possibilities of new technology, and Cold War imperatives, made utopian thinking possible.

And yet their remarkable space programme gave the Soviets some justification for believing that they were capable — quite literally — of aiming for the stars. Why did economic modernisation, a project of similar scope and importance, to which thousands of their best minds had been dedicated, fail so completely?

New Planet, Konstantin Yuon (1921)

Peters’s narrative suggests Glushkov’s plan failed precisely because it promised radical efficiencies, even had it only been partially fulfilled. Its implementation would have required the support of the bureaucracy that benefited from the wasteful processes computerisation sought to eradicate. State ministries enjoying the powers and privileges associated with managing the Soviet economy, and fearing the prospect of looming redundancy, had tried to scupper the OGAS for years prior to Garbuzov’s intervention at that fateful Politburo meeting. The Soviet bureaucracy was more akin to an unregulated market in which self-interested administrators competed for influence than a monolithic structure in which private interests were suppressed.

For Peters the paradox is that the first civilian digital networks were created by “cooperative capitalists, not competitive socialists”. The US succeeded in developing the ARPANET by nurturing a collaborative culture between government, military and civilian institutions that a chaotic Soviet administrative system was unable to cultivate. The moral of the sad story of the Soviet internet is that making new technologies work for the common good depends on mutual obligation and effective regulation: the rule of law, clear governmental structures, and coordination between the public and private sectors.

The moral of the sad story of the Soviet internet is a cautionary tale that haunts our 21st century internet

It’s a cautionary tale that haunts our 21st century internet. Whereas Glushkov’s OGAS was destroyed by competing bureaucrats, today’s “open web”, nurtured in its infancy by collaboration between state, civilian and commercial actors, is being broken apart by private interests, parcelled into closed platforms dominated by giant corporations and exploited by authoritarian governments taking advantage of unprecedented opportunities for monitoring citizens.

Today, Bogdanov’s Red Star is usually remembered for its unabashed utopianism and steampunk contraptions. But Bogdanov was less interested in the technology he dreamt up than the capacity of his Martian engineers to use it wisely. The disciplined Martians had succeeded where fractious humans had so far failed.

Similar thoughts preoccupied Glushkov in his final years. The last book he wrote was intended for young readers: a brief introduction to the possibilities digital networks might offer for — one day — producing Red Plenty. Disillusioned by what his peers had made of his great design, Glushkov invested his hopes in future generations who might yet cultivate the wisdom to make technology work for all.

From the Unity of Science to the Unity of Systems Paradigm: Foundational Importance and Contemporary Relevance of Alexander Bogdanov's Work

The Legacy of Alexander Bogdanov: From Rediscovery to Full Recovery

David G . Rowley

2021, Studies in East European Thought

Friedrich Engels,

Alexander Bogdanov

Show more ▾

Read online: https://rdcu.be/ce7nY Alexander Bogdanov’s first work of philosophy, Basic Elements of the Historical View of Nature, was fundamentally influenced by Friedrich Engels. As a Marxist philosopher seeking to elaborate a comprehensive, systematic, and scientific worldview appropriate for worker–students, Bogdanov found inspiration in Engels’s Anti-Dühring, which provided him with his monist conception of being and his ‘historical view of nature’ and pointed him toward three critical elements of his work: the monism of motion (energy), Spinoza’s naturalist and determinist system, and Charles Darwin’s conception of natural selection. Bogdanov’s overall goal was to demonstrate that in nature, life, the psyche, and society there is no such thing as self-generated motion; all change occurs because of external action. For the individual and for society this means that existence determines consciousness, and societies evolve as a result of their struggle for existence, which is manifested first and foremost in labor.

Bogdanov, "Philosophy of Living Experience" - New Learning Online

Reference: Cope, Bill and Mary Kalantzis, 2020, Making Sense: Reference, Agency and Structure in a Grammar of Multimodal Meaning, Cambridge UK: Cambridge University Press, pp. 34-39.

What Can We Learn from Dystopian Fiction About Climate Change?

If you haven’t heard of cli-fi yet, you are not alone; however, you have probably either read or watched some already.

Support Hyperallergic’s independent arts journalism.

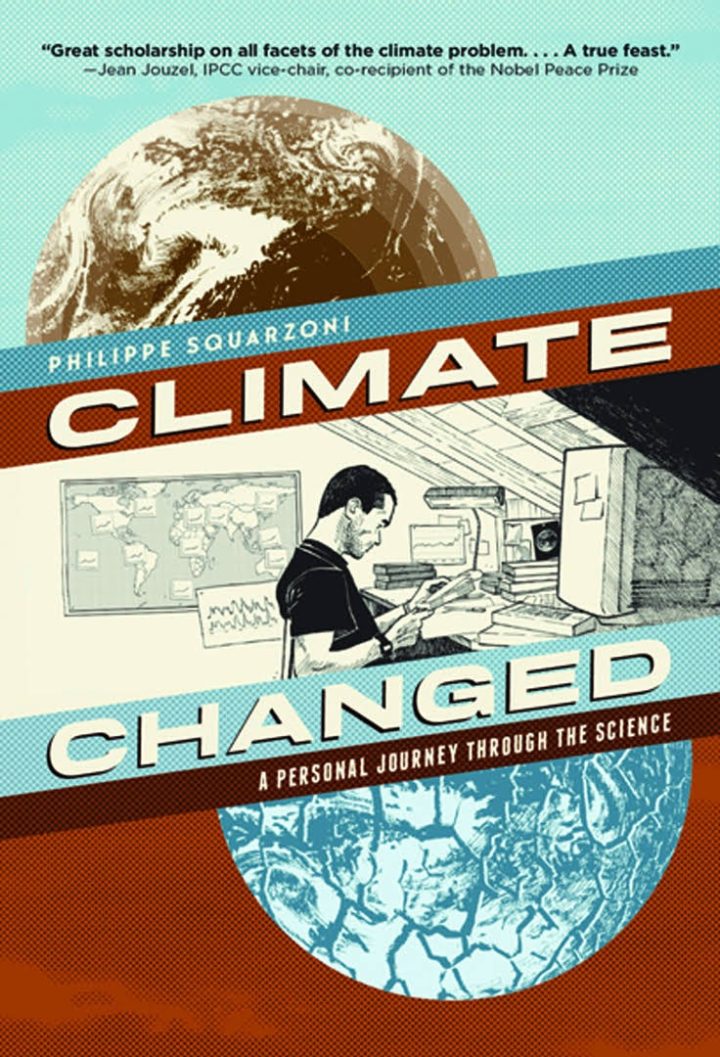

Philippe Squarzoni, Climate Changed: A Personal Journey through the Science, copyright Harry N. Abrams (cover image courtesy of Abrams ComicArts)

Recently, a friend asked on social media, “What do you people read to wind down?” He was referring to the distress we all suffer from the endless negative news coming from the Trump administration. I first suggested sci-fi, but upon remembering that he is a lobbyist for international corporations’ divestiture from the fossil fuel industry, I decided to do some research on sci-fi novels which focus on climate change. That’s when I discovered the so called cli-fi (climate change fiction) genre.

If you haven’t heard of it yet, you are not alone; most of the people I mentioned it to were unaware of it too. However, you have probably either read or watched some cli-fi already. IMBd’s cli-fi page has more than a dozen titles. The Goodreads list of cli-fi novels is over 130 titles long. During the recent months, Lidia Yuknavitch’s The Book of Joan, Zachary Mason’s Void Star, Jane Harper’s The Dry, Margaret Drabble’s The Dark Flood Rises, Kim Stanley Robinson’s New York 2140, Cory Doctorow’s Walkaway, and Sally Abbot’s Closing Down have all hit the shelves described as cli-fi. And, since February of this year, the Chicago Review of Books has published a monthly column on its web site exclusively dedicated to the genre.

Steven Amsterdam,The Things We Didn’t See Coming, copyright Anchor (image courtesy Steven Amsterdam)

Still, there is strong skepticism about the genre’s originality. When I mentioned it to my sci-fi and graphic novel enthusiast friends, they mostly rolled their eyes. Nothing was new about stories focusing on a man-made ecological disasters; they just showed up in other literary categories. For example, Alan Moore’s graphic novel The Swamp Thing, a story based on the consequences of mismanaged nuclear waste was published in 1971. This was also the year in which Dr. Seuss wrote his infamous Lorax, a children’s classic about deforestation and environmental irresponsibility. Even older is Alexander Bogdanov’s communist sci-fi novel, The Red Star – now almost 110 years old – which refers to an ecological crisis very much like ours. Older yet are the ancient religious and mythological Mesopotamian, Hindu, Chinese, and Abrahamic narratives, all of which refer to eco-disasters caused by human mischief.

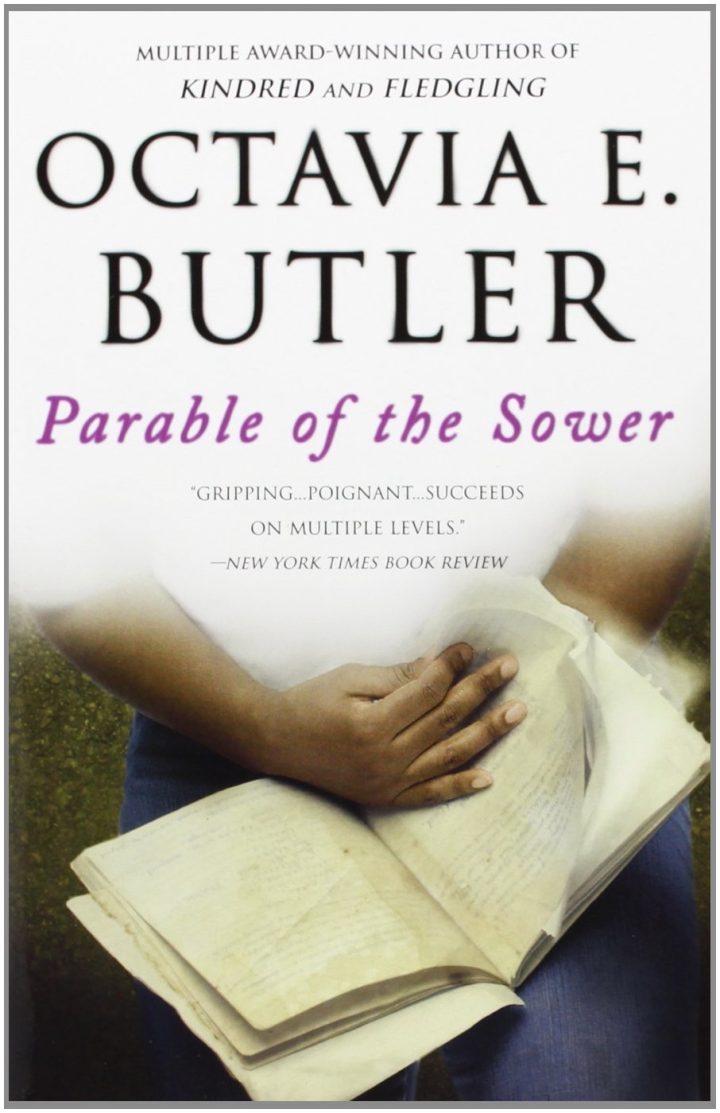

Octavia Butler,, copyright Grand Central Publishing (photo courtesy of Hachette Book Group)

Yet, it is also true that there has been a growing emphasis on ecology during the last two decades in almost every field. In history, there is the so called spatial turn, which refers to a growing interest in geography and ecology. In philosophy, Glenn Albrecht has coined the term solastalgia to describe “a form of psychological or existential distress caused by environmental change, such as mining or climate change.” In the field of geology, there is widespread acknowledgment of the anthropocene, re-popularized in reference to a new epoch defined by the “significant human impact on the Earth’s geology and ecosystem” according to Wikipedia. So, cli-fi can be understood as modern literature’s response to our anxieties about the current consequences of climate change.

In her book, Antonia Mehnert defines cli-fi as:

literature dealing explicitly with anthropogenic climate change,” which “gives insight into the ethical and social ramifications of this unparalleled environmental crisis, reflects on current political conditions that impede action on climate change, explores how risk materializes and effect society, and finally plays an active part in shaping our conception of climate change.

In Wikipedia, cli-fi means the “literature that deals with climate change and global warming. Not necessarily speculative in nature, works of cli-fi may take place in the world as we know it or in the near future.” Hence, cli-fi is not any eco-conscious or eco-apocalyptic literature. It focuses specifically on the current climate change, which we are experiencing. (One place to build your familiarity with cli-fi is to read a recent interview with Dan Bloom, the man who originally coined the term.)

Area X, The Southern Reach Trilogy by Jeff VanderMeer, copyright FSG (image courtesy of Jeff VanderMeer)

Most commonly cited examples of the genre are Cormac McCarthy’s The Road, Kim Stanley Robinson’s the Science in The Capital trilogy, Margaret Atwood’s The Maddaddam trilogy, Nathaniel Rich’s Odds Against Tomorrow, and Barbara Kingsolver’s Flight Behavior. However, Octavia E. Butler’s The Parable of the Sower tops my list, since it predates (in 1993) those novels mentioned above, and it seems to have inspired Atwood’s The Maddaddam trilogy and Cormac McCarthy’s The Road, which are considered pillars of the genre. It also reads like a masterpiece, along the lines of Jean Rhys’s Wide Saragossa Sea. The Parable of the Sower is the coming-of-age story of a an African-American minister’s daughter who lives in a racially mixed and charged community, which gated itself due to an ongoing ecological crisis. A less acknowledged, but excellent novel is Steven Amsterdam’s Things We Didn’t See Coming, which is experimental and enchanting till the very last page. There are large gaps in the story-line, that make it read like Andre Breton’s surreal novel Nadya, but these gaps also mimic how we deal with moments of disaster and stress by taking refuge in collective amnesia. By far the best cli-fi out there must be Jeff VanderMeer’s The Southern Reach trilogy. This is indeed a story about our changing climate: how a territory called Southern Reach becomes a self conscious ecology, starts to remember, thinking, and communicate with human beings. VanderMeer also shifts between genres; the first volume is a horror story that gave me serious nightmares three nights in a row. The second volume is a detective story, and the third one is a mystery.

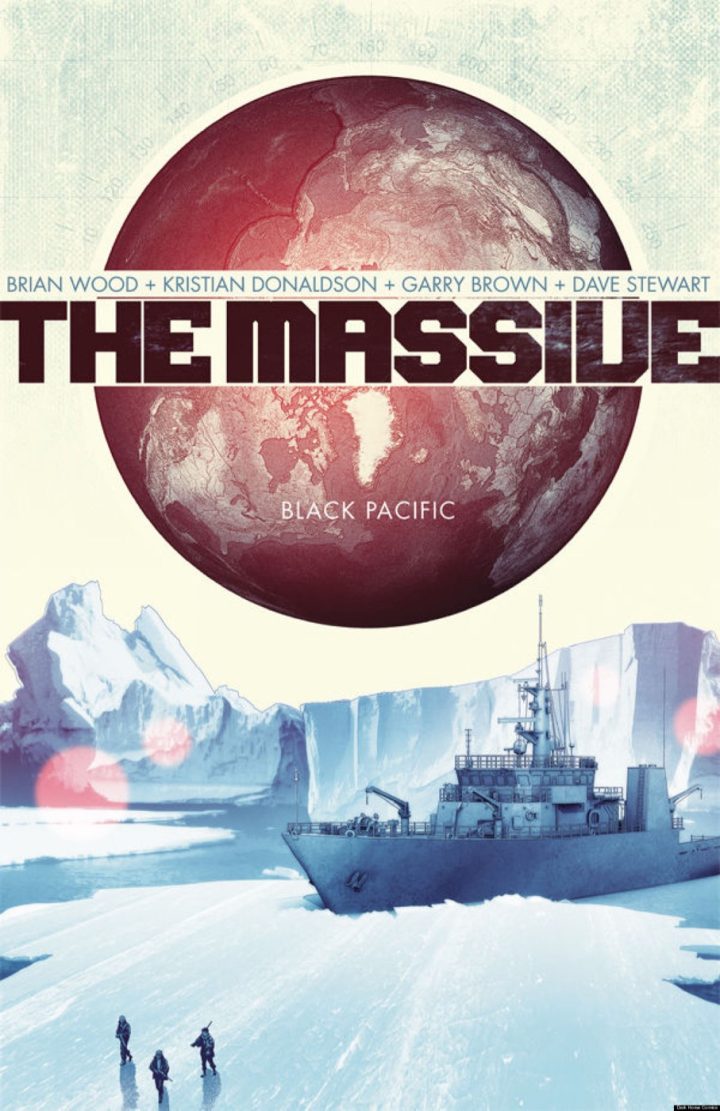

As for graphic novels, Philippe Squarzoni’s award winning Climate Changed, a graphic documentary about his personal struggle to understand climate change is a remarkable artistic feat. Brian Wood’s, The Massive, series relates the story of an eco-activist gang who roam the international seas in the near future, trying to save the planet from further harm. The fifth volume of Paul Chadwick’s Concrete: Think Like a Mountain is also a personal favorite of mine, and the last issue of World War 3 from AK Press is entirely dedicated to climate change chaos.

The Massive, written by Brian Wood and Illustrated by Kristian Donaldson and Garry Brown, copyright Dark Horse Comics (courtesy of Dark Horse Comics)

Last but not the least, I have to mention The Dark Mountain Project, which is active since 2009. It is best known for its Dark Mountain Manifesto, which opens with the statement: “Those who witness extreme social collapse at first hand seldom describe any deep revelation about the truths of human existence. What they do mention, if asked, is their surprise at how easy it is to die.” They have so far published 10 volumes of collected short fiction, poetry, critical essays, graphic fiction, and visual art, all of which explore climate change, and how we write or tell stories about it. Its past editorial boards have included authors like the famous feminist sci-fi writer Ursula La Guin and late cultural critic John Berger. Each volume delivers a serious punch and could generate more debate about cli-fi.

Uncivilised Poetics, Dark Mountain #10, October 2016, copyright The Dark Mountain Project (courtesy of The Dark Mountain Project)

We all know the news about the future of our planet is not good. At the current rate, we have only 60 more harvests left. Marine life is in dramatic decline, and Antarctica has joined the North Pole in melting, which has far more disastrous implications. Weather temperatures are regularly record breaking, sea and river levels are rising, the salinity of our oceans is quickly changing, and the behavior of our atmosphere is evermore unpredictable. Climate refugees are no longer a thing of fiction; parts of Africa and the Middle East will become uninhabitable in the near future, and the World Bank has already advised a number of countries to revise their immigration policies, because they will be hit by a tsunami of migrants. Meanwhile, in the US, we are governed by those who prefer to erase the climate-change data, withdraw from the Paris climate accords, sell our natural reserves to the developers, and eliminate the Environmental Protection Agency. Pathetic as it may sound, cli-fi offers a type of relief from this bigotry. It imagines that one day such idiocies will be washed off clean, and the earth will continue its adventure — probably without us. And even if anyone is left to survive, they would most likely strike a far better covenant with this planet than the one we have at present.

Related

Two Books Take on the Vast Ecological and Social Consequences of Climate Change

May 21, 2019

An Anime Fantasy Combines Myth With Climate Change

January 16, 2020

Many Stories Are Told Through the Typography in Science Fiction Films

December 26, 2018

Murat Cem Mengüç is a freelance writer, artist and a historian who holds a PhD in history of MENA. He is the founder of Studio Teleocene, and currently based outside of Washington, DC. More by Murat Cem Mengüç

By Edmund Berger

Socialism has had a sort of poor track record as of late when it comes to science and technology. From Stalin’s violent repression of Mendelian genetics (and privileging of the pseudo-science of Trofim Lysenko) to the modern contemporary contingencies of anarcho-primitivists, it’s often easy to see what is ostensibly an ideology of advancement oscillating itself between confirmations of the worst despotisms of the dominant, capitalist order, and regressive attitudes towards the raw materials of possible emancipation. The paranoia of computers, simulation, and modelling that blossomed in the 1960s and has persisted until recently recalls, uncomfortably, the anti-scientism of climate change deniers. Where it does embrace technoscience, it adopts them as adjacent to, but not directly bound up within, the emancipatory project. Radical experiments in leftist technoscience, be it Chile’s CyberSyn or the Soviet Union’s own attempts at some form of cybernetic socialism during the Khrushchev years, have fallen by the wayside and are obscured from view. Critical theory continually returns to Situationist discourse, but always seems to focus on those elements that foreshadow insurrectionary anarchism and communization theory. It ignores the constructive side of the ‘construction of situations’ equation – the side on which we can find Constant Niewunhuy’s New Babylon, or Asger Jorn’s celebration of automation.

This is what I think is the greatest strength of Nick Srnicek and Alex William’s Inventing the Future – the reinstallation of technoscience as something intrinsic to a radical, left wing program. Automation, synthetic biology, artificial intelligence, and the planning of complex economic systems all find their application of the largely imaginal[1] horizon of a post-work world. Far from their inevitable brutal application under capitalist control, they offer a vision of technoscience as emerging from long-term state investment (where it emerges from in our current world, anyways) under the direction of democratic control by the population. Alongside this, breaking beyond capitalism requires the repurposing of existing technologies and infrastructures, to unmoor the class structures and exploitative mechanisms designed within their application. Building on Spinoza, the two suggest that “we know not what a sociotechnical body can do. Who among us fully recognizes what untapped potentials await discovery in the technologies that have already been developed? What sorts of postcapitalist communities could be built upon the material we already have?”[2]

Such a program – of developing new technologies through democratic mechanisms, and the repurposing of existing technologies – implies the generation of a sociotechnical literacy (to borrow a term from Arran James). How can a population be brought up to the level of being able to have substantial input into this sort of dynamic reformation? In a time when anti-scientism has yet to wane, how can the working class – and the surplus populations – learn of complexity, modeling systems, and the way that these technics and techniques exist in reciprocal feedback with the ebbs and flows of the population? True, outlets for learning of these things exists, but they remain shunted off in the university (itself repurposed long ago as training grounds for the petite bourgeoisie) or behind exorbitant paywalls. These privatizations of knowledge and knowledge production find their match in cultural attitudes and mores that tell the working class that these forms of knowledge are irrelevant to their daily situations – unless, of course, there is a perceived threat to their pocketbooks. To build a sociotechnical literacy, essential to a future-oriented hegemonic project, thus requires the building of an educational infrastructure that will help people to navigate the cutting edges of technoscience, while also speaking to them on a cultural level.

Importantly, just such a thing was proposed by socialists long ago, in a tendency that was quickly obscured by the hegemony of Leninism in the Soviet Union, the rise of fascism in Europe, and the American postwar sociotechnical hegemony. I would like to offer a cursory sketch of its history.

From Marx to Mach

How is it that we know the external world, and how do we articulate our knowledge of it in the arrays of paradigms and systems that we bundle under that singular world, “science”? For Kant, knowledge could be determined through synthetic a priori, that is, statements can be known to be true before experience can verify them. This was the trail to transcendental idealism – what we call “consciousness” is the result of the intermingling of sensory stimulation and actions of the mind. The mind gives form, shape, and structure to “our conscious experience that sensory stimulation does not provide.”[3] The world is out there, but the mind plays a fundamental role in articulating that world in ways that we can comprehend it.

It was Ernst Mach who challenged several of these key assumptions. If the principle of a priori was the mean to make knowledge possible, he asked, how is the a priori itself possible? The answer, Mach reasoned was not to be found inside philosophical contemplation, or in the relations going on within the mind itself. This was the positive task of science, to discern the functioning of the world in a way that a foundation can be built in order to build up future forms of knowledge and knowledge production. That which the a priori was aligned – theory – was unmoored from its ontological foundation, and treated as little more than an instrument through which the functioning of the world could be discerned. What mattered more than theory was the understanding of knowledge, scientific or otherwise, as sensation itself. Experience of sensation provides the “pure data” through which we can know. As such, the task of the scientist was to provide “economical description(s) of observable phenomena”; in a challenge to Kantian philosophy, knowledge pivoted on the “adapting [of] thoughts to facts and to each other.”[4]

In order for such a task to be carried out, scientific knowledge could no longer be isolated away from one another in differing fields. “It is the object of science to replace, or save experiences, by the reproduction and anticipation of facts in thought. Memory is handier than experience, and often answers the same purpose,” Mach wrote in Memory and Science.[5] In order to provide an ‘economical’ platform for knowledge, a memory system had to be crafted that brought together disparate fields. In other words, a unification of science had to be fostered. This would become the overriding intention of the Vienna Circle that flourished in Austria in various forms from the early 1900s to the 1930s, bringing together numerous and notable natural scientists, mathematicians and philosophers. Vienna, however, was not the only place that Mach’s influence would reverberate.

Between 1904 and 1906, Alexander Bogdanov published a three-volume work bearing the title of Emperio-Monism, detailing an attempted synthesis of Marxist theory and Machist philosophy. His first spin on Mach is a reinterpretation of the sensation necessary for the production of knowledge. In a foreshadow of the contemporary field of science and technology studies, Bogdanov understands science as a collective experience, circulating through and transcending the networks of individuals, apparatuses, and social organizations that produce it. This function, in many regards, recalls the now well-known Marxist concept of the “general intellect” found in Grundrisse.[6] Like the general intellect, Bogdanov’s science is a social function; this, in turn, entails a rendering of sensation as a collective, as opposed to an individual, experience. Yet science has no monopoly on knowledge. Bogdanov had a strong interest in folk knowledge, the kind of knowledge produced by the entanglement of labor and nature. This mode of folk knowledge functions very much like what James C. Scott describes as “metis”, a “mode of reasoning most appropriate to complex material and social tasks where the uncertainties are so daunting that we must trust our (experienced) intuition and feel our way.”[7] What is important in this Marxist-Machism is not so much the superiority of folk knowledge or technical knowledge, but the feedback that exists between and the possibilities of new forms arising from a mutual co-production.

Like any good Marxist, Bogdanov is attentive to the ways in which dominant (particularly capitalist) social organizations ‘flavor’ the way in which science and technology develop, find their articulation, and are deployed within the social field. In Marxist theory, the organization of society takes places through the superstructure, the realm of family, religion, philosophy, science, the institutions of civil society, which is contingent on the dynamics of the base, where one is to find the modes, forces, and relations of production and the economic system that emerges from it. Through this interplay, capitalism gains the expansionist ability to reproduce its relations. Bogdanov, however, finds this dynamic a bit too simplistic, and ultimately too deterministic, to account for the complexity of historical development. His alternative charts a non-linear movement through science, culture, production, and the way that the labor driving this production is organized. To quote Arran Gare, “For Bogdanov economic life is an integral part of social being, and social being is identical to social consciousness; therefore it is knowledge which is the moving force of history and the main line of social progress.”[8]

Reformulating Marx, he argued that social being has two levels, the technical and the organizational. The organization of activity at the technical level generates technical knowledge or technology… As the technical level became more complex, humans came to need organizational forms. This is the realm of ideology, or what has been called in idealist philosophy, the realm of the spirit – concepts, thoughts, norms, all of those things that would be called ideas in the broadest sense of the word. Bogdanov saw no difference between technical and ideological labor… Techniques are the very essence of human social existence and the primary matrix of social relations, but ideology, the entire sphere of social life outside of the technical process, is also a vital force.[9]

As McKenzie Wark writes, Bogdanov’s perspective is a “labor point of view”, perhaps even more so than Marx’s own, in that while he situates the sensation of experience as the baseline for the production of knowledge, which in turn feeds into the organization of society, as a laboring act committed not by the individual, but by the collective of laborers. “…scientists, artists, and philosophers,” like Mach would argue, “are ‘organizers of experience’”,[10] and communicate this experience through the structures of culture. Culture, then, is intricately bound to the ways in which knowledge is produced and articulated, and thus it is through this complex interplay that culture predicates the organization of production – a starkly different portrait than the predication of culture on the organization of production, as the Marxist base-superstructure dynamic would have it. As long as bourgeois culture persisted, experience would be organized in a way that perpetuated capitalist domination. An attempt to strike out against capitalism without first paying heed to the fostering a new culture that would replace that of the bourgeoisie would ultimately be doomed to fail.

Bogdanov would become one of the Lenin’s major rivals in the early days of the Soviet Union, and his reformulation of Marx clearly challenged many of the essential assumptions of the vanguard party, which carried out its actions on the notion that simply reorganizing the superstructure would fundamentally transform the base. It is for this reason that Bogdanov remains relatively unknown, even on the left, having been quite literally written out of history by Lenin. There is no need to recount the rivalry between Bogdanov and Lenin here, and its relation to wider power struggles in the fledgling socialist republic (though I cover some of it in my earlier essay All That is Solid Melts). What is important here are Bogdanov’s two attempts to build platforms for a revolution in organization, through which a new world can be glimpsed through productive education. The first of these is Proletkult, which attempted to provide the workers with the means in which to create their own culture, and the second is tektology, a sort of ‘science of sciences’ (not dissimilar to the Machist gambit of unifying science) that would allow workers to transcend their status as cogs in the capitalist machine and become worker-engineers, and ultimately worker-scientists.

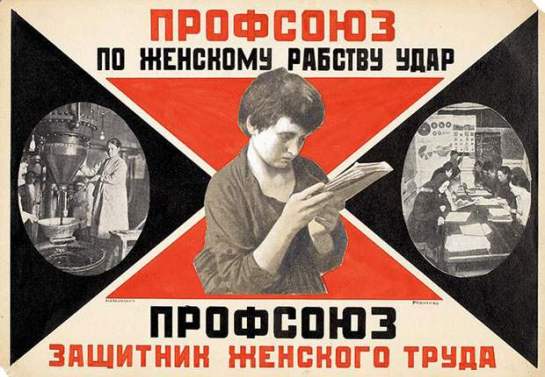

Srnicek and Williams argue that the left must construct a “counter-hegemonic project” capable of contesting neoliberalism, one that “enables marginal and oppressed groups to transform the balance of power in a society and bring about a new common sense.”[11] This was precisely the program that Bogdanov conceived of with Prolekult; in his own words, “the inherent condition of Bolshevism was to ‘create as from now on in the midst of existing society the great proletarian culture, stronger and more structured than the culture of the bourgeois classes in decline and more immeasurably freer and more creative.”[12] Socialism was not some far-off goal to be attained in the future, following the heroic negation of the bourgeoisie’s power over the proletariat. It was emergent, right in the social fields of capitalism itself, and simply needed the ability to extend this emergence into the world. Funded by the People’s Commissariat for Education (led by a key Bogdanov ally, Anatoly Lunacharsky), Proletkult flourished in a network of individuals and institutions across multiple cities, often aligned directly with the leading trade unions. Arts and crafts studios, painting and cinema workshops, theater and cinematography courses sprung up, located primarily in direct proximity to factory shop-floors. The influence of the most cutting-edge and technologically-oriented of the modernist avant-gardes flowed through these hotbeds of “proletarian art”, including futurism and constructivism. Writes McKenzie Wark:

Proletkult was a movement with a mission: to change labor, by merging art and work; to change everyday life, by developing the collaborative life within the city and changing gender roles and norms; and to change affect, to create new structures of feeling, to overcome the emotional friction of organizing the labor that in turn organizes nature around its appetites.[13]

Importantly, Proletkult was to break with the student-teacher dynamic that characterizes the majority of education, cultural or otherwise. Just as James Scott defined metis as a sort of labor-knowledge that developed through cooperation within and against nature, the proletarian culture was to be self-generating from the self-organization of the workers themselves. Platon Kerzhentsev, a Bolshevik party official and Proletkult leader, wrote that the network’s studio systems “break with the principle of authoritarianism and are built on the comradely basis of equality and collective creativity.”[14] Self-organization, the Proletkultists recognized, was contingent on the fostering of physical and mental infrastructures, and the subsequent politics of organizing the environment. A leftist, proletarian hegemony had to be built towards, and was never a given against either the bourgeois hegemony or even that of the Marxist-Leninist party – as the subsequent dismantling of Proletkult, and the later dismantling of the Soviet Union, would show.

If the proletariat was to become the ‘organizers of experience’, this ambition could not be limited to the production of culture alone. A proletarian culture necessarily entailed a proletarian science, one that like Proletkult could be self-organizing and capable of superseding the scientific knowledge/folk knowledge divide. Such was the goal of tektology, defined by Bogdanov as “a general study of the forms and laws of organization of all elements of nature, of ourselves, practice, and thought.”[15] The debt to Mach is clear: tektology would provide an ‘economical description’ of experience, while also moving towards a unity of science that allowed the translation of insights and practices from one field to the next. As an educational platform, it would ostensibly also serve as the platform for future forms of scientific thought, theory, and practice. It is interesting to note that Bogdanov borrowed the term “tektology” not from the Machist continuum, but from Ernest Haeckel; Haeckel, also one of the leading proponents of Darwinian theories of evolution, had been a major proponent of German Naturphilosophie – the school of thought generally associated with Fichte and Schelling that sought to establish the foundation for the natural sciences through the elucidation of general rules and forms of organization governing nature in its totality. A Machist-Marxist tektology would seek to no longer maintain this effort in the hallowed halls of philosophy, but to instead inscribe in the practice of labor.

“The methods of all sciences are for tektology only modes of organization supplied by experience,” wrote Bogdanov.[16] The organization established by natural processes proceeds all other forms of organization, which form themselves within and against nature itself. Thus, all questions tend towards the question of organization. The concept of the dialectical synthesis has no bearing here; organization was never in the primordial past some harmonious totality, nor will it be in the future – communist or otherwise. Nature naturally disrupts all bids for utopia. If one can experience nature, and thus know it, make it into science, this experience is based on pre-existing organizational platforms (such as the self-organizing proletarian culture emerging from the Proletkult infrastructure). Tektology, therefore, “was meant to be a design practice for organizing organization, conceived under very real conditions of scarcity and disorganization, but under no illusions that a rosy and harmonious future lay ahead.”[17] If proletarian science was to take root, it needed an infrastructure that allowed the navigation of this tumultuous hyperchaos. Bogdanov lays out a variety of key concepts, which for him served as the essential baseline for the general rule sets governing this chaos:[18]

Environment – that which is always there, always there and composed of systems

Conjunction – the coming-together and overlapping of two systems embedded in this wider nature

Boundary – the insulation for a given system that must be “breached” in order for conjunction to take place

Linkage – the intermingling and interconnection of elements from different system, taking place in the conjunction’s overlapping zone

Ingression – the emergence of a new system or systems from the linkage

Disingression – the mutual breakdown of systems in conjunction

Equilibrium – the act of boundary stabilization in the event of disingression

Crisis – the movement of systems towards a point of disequilibrium

Conservative selection – the preservation or destruction of an organizational system in an unchanging environment

Progressive selection – “a change in the number of elements in a system that maintains a dynamic equilibrium with a changing environment.”

Egression – a system composed of multiple subsystems, usually bound up together under the direction of a primary system

Degression – the remnants or leftovers of a system’s actions

As this handful of concepts and brief, truncated definitions, the swerving of systems from stability to instability and back again is central to Bogdanov’s tektology. As a science of systems, the concern of tektology is not only the ability of the workers to higher modes of intellect and organization, but to discern the patterns of self-organization latent in nature at all scales. Even more importantly is the recognition that systems operating on different scales interact with one another, generating new systems or collapsing the old ones in kind. The self-organization of knowledge, labor, and culture, then, is established in the context of a wider swath of self-organizing systems, and remains perpetually embedded within them. Bogdanov’s tektology, in other words, anticipates the whole of second-order cybernetics, systems theory, and complexity theory, albeit in a rather reduced and premature way. The reductionist nature of his approach, however, cannot be dismissed outright, for his is simply an attempt to present what Mach had suggested: the collecting and arrangement of generalized experiences, through which the ability to know can flourish.

Indeed, many have suggested that German translations of Bogdanov’s tektological reflections influenced both Ludwig von Bertalanffy, the father of general of general systems theory, and Norbert Wiener, the leading theorist and proponent of cybernetics in the years following World War 2. While this remains the subject of debate, there are remarkable congruencies between his work and those of these later thinkers. To quote Fritjof Capra and Pier Luigi Luisi,

Like Bertalanffy, Bogdanov recognized that living systems are open systems that operate far from equilibrium, and he carefully studied their regulation and self-regulation processes. A system for which there is no need of external regulation, because the system regulates itself, is called a “biregulator” in Bogdanov’s language. Using the example of the centrifugal governor of a steam engine to illustrate self-regulation, as the cyberneticists would do several decades later, Bogdanov essentially described the mechanism defined as feedback by Norbert Wiener, which became a central concept of cybernetics.[19]

For the descendants of Bertalanffy and Wiener, such as the complexity theorists working at the Santa Fe Institute, these complex systems become tinged with the attributes of the neoliberal ideology. The ability of systems to self-organize becomes the self-organization of free agents moving and exchanging in the marketplace, swirling about and coalescing into the beautiful swarm of commerce. Tektology stakes itself out against these interpretations far in advance, with Bogdanov having attacked the atomistic worldview as the basis for capitalism’s projection of hyper-individualism radiated from the belief in the self’s absolute agency. While indebted to Mach’s own critique of atomism, tektology, like Proletkult, always maintained itself in the context of collectivity, of generalized experience and intellect encompassing multiple bodies encountering nature together. Everything unfolds under the socialist horizon.

Empiriomonism | Historical Materialism

Buy softcover (Haymarket)

Jan 2020

ISBN

978-90-04-30031-6

Essays in Philosophy, Books 1–3

Alexander Aleksandrovich Bogdanov

Editor: David Rowley

Author: Alexander Aleksandrovich Bogdanov

Empiriomonism is Alexander Bogdanov’s scientific-philosophical substantiation of Marxism. In Books One and Two, he combines Ernst Mach’s and Richard Avenarius’s neutral monist philosophy with the theory of psychophysical parallelism and systematically demonstrates that human psyches are thoroughly natural and are subject to nature’s laws. In Book Three, Bogdanov argues that empiriomonism is superior to G. V. Plekhanov’s outdated materialism and shows how the principles of empiriomonism solve the basic problem of historical materialism: how a society’s material base causally determines its ways of thinking. Bogdanov concludes that empiriomonism is of the same order as materialist systems, and, since it is the ideology of the productive forces of society, it is a Marxist philosophy.

Biographical note

David G. Rowley, Ph.D (1982), University of Michigan, is Emeritus Professor , University of Wisconsin-Platteville. He has published research on Alexander Bogdanov and is the translator of Volume 8 of the Bogdanov Library, The Philosophy of Living Experience (Brill, 2016).

Readership

All interested in Russian intellectual history, Russian Marxism in the revolutionary era, the philosophy of historical materialism, and the philosophy of mind.

Table of contents

Preface

The Autobiography of Alexander Bogdanov

Bogdanov as a Thinker

V.A. Bazarov

Book One

1 The Ideal of Cognition (Empiriomonism of the Physical and the Psychical)

2 Life and the Psyche

1 The Realm of Experiences

2 Psychoenergetics

3 The Monist Conception of Life

3 Universum (Empiriomonism of the Separate and the Continuous)

Conclusion to Book One

Book Two

4 The ‘Thing-in-Itself’ from the Perspective of Empiriomonism

5 Psychical Selection (Empiriomonism in the Theory of the Psyche)

1 Foundations of the Method

2 Applications of the Method (Illustrations)

6 Two Theories of the Vital-Differential

Book Three

7 Preface to Book Three

1 Three Materialisms

2 Energetics and Empiriocriticism

3 The Path of Empiriomonism

4 Regarding Eclecticism and Monism

8 Social Selection (Foundations of the Method)

9 Historical Monism

1 Main Lines of Development

2 Classes and Groups

10 Self-Awareness of Philosophy (The Origin of Empiriomonism)

Bibliography

Index