Buddhist nuns walk past a poster showing Chinese President Xin Jinping and former Chinese leaders Jiang Zemin, Mao Zedong, Deng Xiaoping and Hu Jintao in Potala Palace square in Lhasa, during a government-organised tour of the Tibet Autonomous Region, China, October 15, 2020. Picture taken October 15, 2020. REUTERS/Thomas Peter (REUTERS)8 min read . Updated: 31 Oct 2020, 08:15 AM ISTBloomberg

Buddhist nuns walk past a poster showing Chinese President Xin Jinping and former Chinese leaders Jiang Zemin, Mao Zedong, Deng Xiaoping and Hu Jintao in Potala Palace square in Lhasa, during a government-organised tour of the Tibet Autonomous Region, China, October 15, 2020. Picture taken October 15, 2020. REUTERS/Thomas Peter (REUTERS)8 min read . Updated: 31 Oct 2020, 08:15 AM ISTBloombergFor China, showcasing Tibetans singing the Communist Party’s praises helps affirm its legitimacy to rule the region

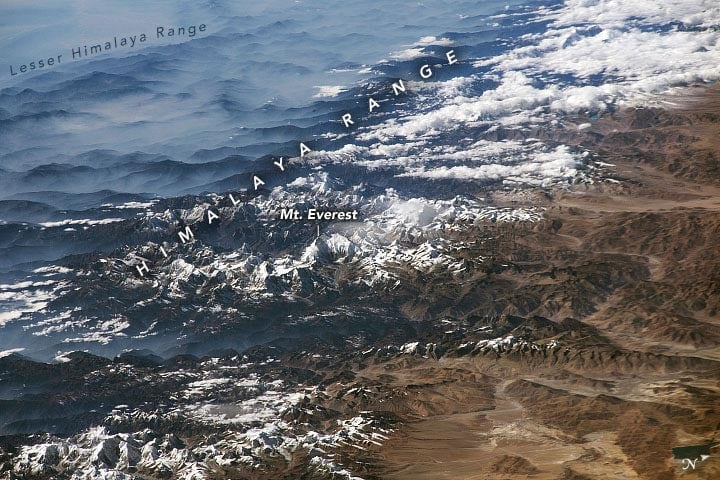

In Tibet, often called the 'Roof of the World' because of its high elevation along the Himalayas, ethnic Tibetans comprise about 90% of the 3.5 million people spread across an area the size of South Africa

Sitting in a home built by Chinese authorities near Tibet’s capital of Lhasa, one of the highest cities in the world, Sunnamdanba tells foreign journalists on a government-sponsored tour how much the Communist Party has improved life -- and how irrelevant religion has become for him.

“I could have never dreamed my life would be so good," the 41-year-old father of two, who by tradition uses only one name, said in comments translated by a local official. Foreign journalists can only report from the region on trips organized by the government.

Asked about the Dalai Lama, Tibet’s 85-year-old spiritual leader now living in exile and condemned by China as a separatist, Sunnamdanba said: “I never met him and I don’t understand him."

And Buddhism, the religion that has for more than a millennium been the foundation of Tibetan culture? “I spend most of my time and energy now on work and making a living," he said. “There’s less time to spend on religion."

Why hang a portrait of President Xi Jinping in your living room? “None of this could have happened without the party."

Legitimacy to Rule

For China, showcasing Tibetans singing the Communist Party’s praises helps affirm its legitimacy to rule the region, something that’s weighed on Beijing’s ties with the West since a failed uprising in 1959 forced the Dalai Lama to flee and set up a government-in-exile in northern Indian. It’s become more important recently as politicians in the U.S., Europe and India accuse China of using forced labor, detentions and re-education campaigns to assimilate ethnic minorities in its borderlands.

The Trump administration’s newly appointed special envoy for Tibetan issues met with the head of the exiled Tibetan administration this month, generating outrage from China. India, which only recognized Beijing’s sovereignty over the area in 2003, also recently venerated a Tibetan soldier who died fighting against China this year in the worst fighting along the border since a 1962 war.

Tensions have risen in other areas as well. Earlier this year, a Chinese government effort to make Mandarin Chinese the language of instruction at schools in a region inhabited by ethnic Mongolians sparked street protests. And in Xinjiang, a province directly north of Tibet, outrage over China’s move to detain more than a million minority Uighur Muslims in re-education camps has led some U.S. lawmakers to push for the actions to be declared “genocide."

Xi has personally defended the moves in Xinjiang, saying they are necessary to stem terrorism and improve the lives of people. In comments last month, he called the party’s policies “completely correct," urged more economic development and pushed for more nationalism in education to “allow the sense of Chinese identity to take root in people."

Sinofication of Buddhism

At a meeting on Tibet issues in August, Xi told officials to “actively guide Tibetan Buddhism to adapt to socialist society, and promote the Sinofication of Tibetan Buddhism."

In Tibet, often called the “Roof of the World" because of its high elevation along the Himalayas, ethnic Tibetans comprise about 90% of the 3.5 million people spread across an area the size of South Africa. Their language bears no relation to Chinese, most are Buddhists, and many consider the Dalai Lama their spiritual head -- if not their political leader.

In 2008, deadly riots erupted in Lhasa, leaving at least a dozen dead. A spate of self-immolations by ethnic Tibetans followed a few years later, with the Dalai Lama’s followers and human-rights activists attributing the actions to government oppression. Beijing has blamed the Dalai Lama for fomenting the unrest, and that sentiment continues to be expressed by officials today who see religion as the root cause of some of Tibet’s biggest challenges.

“Due to some outdated conventions and bad habits -- particularly the negative influence of religion, people put more attention on the afterlife, and their desire to pursue better living this life is relatively weaker," Tibet Governor Qi Zhala told reporters at a briefing that was part of the trip. “Therefore, in Tibet, we’ll need to not only feed the stomach, but also fix the mind."

Tibetans are allowed to continue with religious practices only under strict controls: Those who openly show reverence and support for the Dalai Lama can face harsh punishment.

‘This Is How You Control Tibet’

“Now they want Buddhism to be taught in Chinese language," Lobsang Sangay, president of Tibet’s exiled government, told a seminar in Washington on Sept. 28. “This is how you control Tibet and this is how you control the Himalaya belt. This is how you control Asia."

But Beijing is also investing heavily in Tibet, betting that new roads, jobs, better housing and improved access to education and healthcare will bring stability to the region. It’s also counting on modern life to erode the sway that religion has had over Tibet since the seventh century.

“A gift makes you indebted to the giver," said Emily Yeh, a professor at the University of Colorado, Boulder, who is the author of the book “Taming Tibet: Landscape Transformation and the Gift of Chinese Development." “The bottom line is loyalty to the state and the party."

Tibet is crucial to Beijing for strategic purposes. Its mountainous terrain abuts a 4,000-kilometer (2,500-mile) border with countries including India, Nepal and Myanmar, forming a natural security barrier. Beijing has recently reinforced troops stationed in Tibet as it prepares for a long winter in its high-altitude standoff with India.

“To govern a country, it’s necessary to govern the border," Xi told the Tibet symposium in August, where the party set policy directions for developing the region. “To govern the border, it’s required to stabilize Tibet first."

Family Relocations

For Xi, the key to snuffing out calls for independence in Tibet and strengthening Communist Party rule is delivering economic growth in one of China’s poorest regions.

Since 2016, China has spent more than $11 billion on poverty alleviation efforts in Tibet. Authorities say they’ve pulled 628,000 people above the country’s absolute poverty threshold, which Beijing currently defines as those with annual earnings of less than approximately $600 -- or $1.64 a day.

Those efforts have included building roads to far-flung villages, securing safe drinking water and providing access to health care. But they’ve also fueled concern about the loss of Tibetan culture, in particularly due to widespread relocations of families.

Sunnamdanba is among roughly 266,000 Tibetans who have been relocated to new villages over the past five years as part of Xi’s poverty alleviation campaign. He said his family now makes about $13,000 annually, four times what it used to make in a good year, from his job as a security guard, his wife’s work as a cleaner and renting out three rooms in their new home to Chinese tourists.

The government’s stance that it hasn’t forced anyone to move as part of the poverty alleviation drive was backed up by an ethnic Tibetan researcher who studies relocations in the region. Asking not to be named for fear of retribution, the researcher said he is aware of villages where only two out of 120 households took up the offer to be relocated.

However, a new drive by the government to move 130,000 people from fragile ecosystems at high elevations has been less flexible. According to the researcher, villagers in these locations aren’t given a choice.

‘I Believe in the Party’

Those presented to reporters on the trip appeared happy to change locations. Among them were 35-year-old Luoce, who used to graze animals on his grassland some 5,000 meters (16,000 feet) above sea level, where he says the thin air gave him nosebleeds.

In 2017, he moved to a so-called relocation village and now works as a security guard and firefighter. His earnings have tripled thanks to his wages and various government subsidies, including one he receives to not graze animals on his land for environmental reasons. Luoce’s goal is to give his seven children the education he never received.

“I believe in the party and in science more than I believe in religion," he said through a government translator.

Still, a poorly executed relocation program could also leave people worse off and foment the very kind of instability improved economic conditions were meant to prevent.

A notable example of this occurred in Inner Mongolia about a decade ago, when provincial authorities relocated herdsmen from the steppe to so-called milk villages. China’s dairy industry imploded shortly afterward following a tainted milk scandal, forcing many of the herdsman to eke out a living doing odd jobs.

Disadvantaged Underclass

Large-scale resettlement involves major changes to social structures, family links, culture, lifestyle, communities and class structure, according to Robbie Barnett, who headed Columbia University’s Modern Tibetan Studies Program until 2018 and has written about the region since the 1980s.

“It’s impossible to overstate the enormity of these new forms of development and economic policy in Tibet and Tibetan areas, particularly resettlement," he said. “To put it at its crudest, the risk is that, while some will prosper, many farming and herding communities will be transformed into a dislocated, disadvantaged underclass."

Officials interviewed during the reporting trip spoke extensively about that risk, and highlighted two solutions: Teaching Tibetans new skills to make money, and expanding education.

Outside Shigatse, Tibet’s second-largest city, low-income families are growing mushrooms -- something Tibetans haven’t traditionally done -- and then selling them to a government-financed company. More than 600 kilometers away in Nyingchi, authorities are planning to spend more than $100 million on a vocational training center designed for students who failed a test to continue onto high school after compulsory education in Tibet ends after grade nine.

One of those students is Suolanyixi, the 19-year-old son of pepper farmers. He’s already mastered the cappuccino in his quest to become a professional barista, and hopes to one day land a job at one of the roughly half-dozen five-star hotels in Lhasa.

And while none of the other students who’ve studied coffee making at the school has ever gotten a job outside of Tibet, Suolanyixi is not ready to rule out the thought -- something that would further the Communist Party’s goal of integrating the region with the rest of China. “Maybe if I am lucky," he said in fluent Mandarin Chinese.