Aug 18, 2021

Motherboard

From the surface of Earth it seems the stars and galaxies are randomly placed throughout the universe. But step back to a galactic scale, and a mysterious network of roads and hubs emerges. This is the Cosmic Web, and we are just beginning to learn how it underlies the nature of the cosmos. Mordecai-Mark Mac Low and Carter Emmart from the American Museum of Natural History take us on a tour of the Cosmic Web.

Mapping the universe's earliest structures with COSMOS-webb

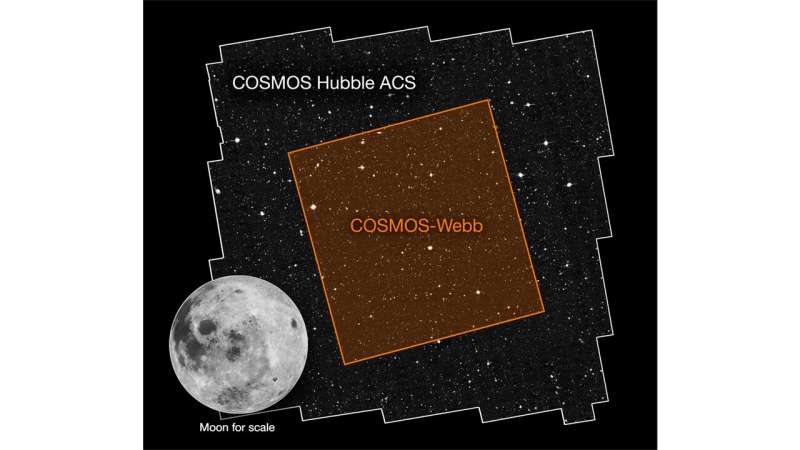

When NASA's James Webb Space Telescope begins science operations in 2022, one of its first tasks will be an ambitious program to map the earliest structures in the universe. Called COSMOS-Webb, this wide and deep survey of half a million galaxies is the largest project Webb will undertake during its first year.

With more than 200 hours of observing time, COSMOS-Webb will survey a large patch of the sky—0.6 square degrees—with the Near-Infrared Camera (NIRCam). That's the size of three full moons. It will simultaneously map a smaller area with the Mid-Infrared Instrument (MIRI).

"It's a large chunk of sky, which is pretty unique to the COSMOS-Webb program. Most Webb programs are drilling very deep, like pencil-beam surveys that are studying tiny patches of sky," explained Caitlin Casey, an assistant professor at the University of Texas at Austin and co-leader of the COSMOS-Webb program. "Because we're covering such a large area, we can look at large-scale structures at the dawn of galaxy formation. We will also look for some of the rarest galaxies that existed early on, as well as map the large-scale dark matter distribution of galaxies out to very early times."

(Dark matter does not absorb, reflect, or emit light, so it cannot be seen directly. We know that dark matter exists because of the effect it has on objects that we can observe.)

COSMOS-Webb will study half a million galaxies with multi-band, high-resolution, near-infrared imaging, and an unprecedented 32,000 galaxies in the mid infrared. With its rapid public release of the data, this survey will be a primary legacy dataset from Webb for scientists worldwide studying galaxies beyond the Milky Way.

Building on Hubble's achievements

The COSMOS survey began in 2002 as a Hubble program to image a much larger patch of sky, about the area of 10 full moons. From there, the collaboration snowballed to include most of the world's major telescopes on Earth and in space. Now COSMOS is a multi-wavelength survey that covers the entire spectrum from the X-ray through the radio.

Because of its location on the sky, the COSMOS field is accessible to observatories around the world. Located on the celestial equator, it can be studied from both the northern and southern hemispheres, resulting in a rich and diverse treasury of data.

"COSMOS has become the survey that a lot of extragalactic scientists go to in order to conduct their analyses because the data products are so widely available, and because it covers such a wide area of the sky," said Rochester Institute of Technology's Jeyhan Kartaltepe, assistant professor of physics and co-leader of the COSMOS-Webb program. "COSMOS-Webb is the next installment of that, where we're using Webb to extend our coverage in the near- and mid-infrared part of the spectrum, and therefore pushing out our horizon, how far away we're able to see."

The ambitious COSMOS-Webb will build upon previous discoveries to make advances in three particular areas of study, including: revolutionizing our understanding of the Reionization Era; looking for early, fully evolved galaxies; and learning how dark matter evolved with galaxies' stellar content.

Goal 1: Revolutionizing our understanding of the reionization era

Soon after the big bang, the universe was completely dark. Stars and galaxies, which bathe the cosmos in light, had not yet formed. Instead, the universe consisted of a primordial soup of neutral hydrogen and helium atoms and invisible dark matter. This is called the cosmic dark ages.

After several hundred million years, the first stars and galaxies emerged and provided energy to reionize the early universe. This energy ripped apart the hydrogen atoms that filled the universe, giving them an electric charge and ending the cosmic dark ages. This new era where the universe was flooded with light is called the Reionization Era.

The first goal of COSMOS-Webb focuses on this epoch of reionization, which took place from 400,000 to 1 billion years after the big bang. Reionization likely happened in little pockets, not all at once. COSMOS-Webb will look for bubbles showing where the first pockets of the early universe were reionized. The team aims to map the scale of these reionization bubbles.

"Hubble has done a great job of finding handfuls of these galaxies out to early times, but we need thousands more galaxies to understand the reionization process," explained Casey.

Scientists don't even know what kind of galaxies ushered in the Reionization Era, whether they're very massive or relatively low-mass systems. COSMOS-Webb will have a unique ability to find very massive, rare galaxies and see what their distribution is like in large-scale structures. So, are the galaxies responsible for reionization living in the equivalent of a cosmic metropolis, or are they mostly evenly distributed across space? Only a survey the size of COSMOS-Webb can help scientists to answer this.

Goal 2: Looking for early, fully evolved galaxies

COSMOS-Webb will search for very early, fully evolved galaxies that shut down star birth in the first 2 billion years after the big bang. Hubble has found a handful of these galaxies, which challenge existing models about how the universe formed. Scientists struggle to explain how these galaxies could have old stars and not be forming any new stars so early in the history of the universe.

With a large survey like COSMOS-Webb, the team will find many of these rare galaxies. They plan detailed studies of these galaxies to understand how they could have evolved so rapidly and turned off star formation so early.

Goal 3: Learning how dark matter evolved with galaxies' stellar content

COSMOS-Webb will give scientists insight into how dark matter in galaxies has evolved with the galaxies' stellar content over the universe's lifetime.

Galaxies are made of two types of matter: normal, luminous matter that we see in stars and other objects, and invisible dark matter, which is often more massive than the galaxy and can surround it in an extended halo. Those two kinds of matter are intertwined in galaxy formation and evolution. However, presently there's not much knowledge about how the dark matter mass in the halos of galaxies formed, and how that dark matter impacts the formation of the galaxies.

COSMOS-Webb will shed light on this process by allowing scientists to directly measure these dark matter halos through "weak lensing." The gravity from any type of mass—whether it's dark or luminous—can serve as a lens to "bend" the light we see from more distant galaxies. Weak lensing distorts the apparent shape of background galaxies, so when a halo is located in front of other galaxies, scientists can directly measure the mass of the halo's dark matter.

"For the first time, we'll be able to measure the relationship between the dark matter mass and the luminous mass of galaxies back to the first 2 billion years of cosmic time," said team member Anton Koekemoer, a research astronomer at the Space Telescope Science Institute in Baltimore, who helped design the program's observing strategy and is in charge of constructing all the images from the program. "That's a crucial epoch for us to try to understand how the galaxies' mass was first put in place, and how that's driven by the dark matter halos. And that can then feed indirectly into our understanding of galaxy formation."

Quickly sharing data with the community

COSMOS-Webb is a Treasury program, which by definition is designed to create datasets of lasting scientific value. Treasury Programs strive to solve multiple scientific problems with a single, coherent dataset. Data taken under a Treasury Program usually has no exclusive access period, enabling immediate analysis by other researchers.

"As a Treasury Program, you are committing to quickly releasing your data and your data products to the community," explained Kartaltepe. "We're going to produce this community resource and make it publicly available so that the rest of the community can use it in their scientific analyses."

Koekemoer added, "A Treasury Program commits to making publicly available all these science products so that anyone in the community, even at very small institutions, can have the same, equal access to the data products and then just do the science."

COSMOS-Webb is a Cycle 1 General Observers program. General Observers programs were competitively selected using a dual-anonymous review system, the same system that is used to allocate time on Hubble.

The James Webb Space Telescope will be the world's premier space science observatory when it launches in 2021. Webb will solve mysteries in our solar system, look beyond to distant worlds around other stars, and probe the mysterious structures and origins of our universe and our place in it. Webb is an international program led by NASA with its partners, ESA (European Space Agency) and the Canadian Space Agency.

Image: Hubble's treasure chest of galaxie

Provided by Space Telescope Science Institute

:focal(1199x902:1200x903)/https://public-media.si-cdn.com/filer/ef/ba/efbaa4a7-77ac-423d-9716-c6c8f8e11660/dust_bowl_-_dallas_south_dakota_1936.jpg)

/https://public-media.si-cdn.com/filer/6c/da/6cdae65e-dcd1-4719-9ab6-354ca1faa2b8/dust-bluebkg-scaled.jpg)

/https://public-media.si-cdn.com/filer/0b/02/0b02deec-86e8-4c3f-97d9-778b72fd1539/julaug2021_a29_prologue.jpg)

:focal(807x601:808x602)/https://public-media.si-cdn.com/filer/16/fa/16fa738e-3e65-4f3f-9c84-21fc6a449469/a-21-dscn0079_aerial-photo-loc-b-2005-rpotts_jc-edits_web.jpg)

/https://public-media.si-cdn.com/filer/09/33/093310e9-7728-4118-9837-88902f1d11ef/a-22-olorgesailie-achulean-handaxes-msa-points-pigments-white-background_web.jpg)

/https://public-media.si-cdn.com/filer/55/db/55db9e5e-5597-4430-ba9d-cb886ab825ed/b-7-olorg2012_img_13740188_jclark_web.jpg)

:focal(959x612:960x613)/https://public-media.si-cdn.com/filer/fd/5a/fd5a0948-8af9-4998-8d57-6de55340aae0/1_schaedel_killig.jpeg)

/https://public-media.si-cdn.com/filer/db/08/db08d525-e9a9-418d-a8ed-d41c1c175d8f/csm_2_schaedel_killig_7462d36ad0.jpeg)