Shock waves, landslides may have caused 'rare' volcano tsunami: experts

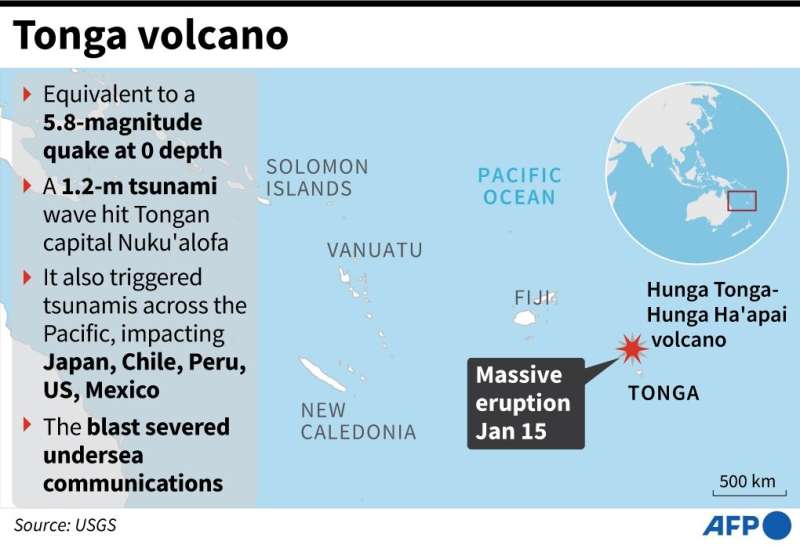

A rare volcano-triggered tsunami sparked by the eruption of Hunga Tonga-Hunga Ha'apai in Tonga could have been caused by shock waves or shifting underwater land, experts said Monday.

"A volcanic-source tsunami event is rare but not unprecedented," a post on the website for New Zealand's geological hazard monitoring system GNS said Monday.

GNS Tsunami Duty Officer Jonathan Hanson said it probably occurred in part thanks to a previous eruption of the same volcano one day earlier.

"It is likely that the earlier 14 January eruption blew away part of the volcano above water, so water flowed into the extremely hot vent," wrote Hanson.

"This meant that the Saturday evening eruption initially occurred underwater and exploded through the ocean, causing a widespread tsunami," he said.

Two days after Hunga Tonga-Hunga Ha'apai's massive explosion, the nation's 100,000 population remained virtually cut off from the rest of the world with crippled communications and stalled emergency relief efforts.

The volcano cloaked Tonga in a film of ash, sent a column of ash and gas 20 kilometres into the air and shock waves that could be seen from space rippling across the planet.

It also triggered a Pacific-wide tsunami whose waves were strong enough to drown two women in Peru more than 10,000 kilometres (6,000 miles) away.

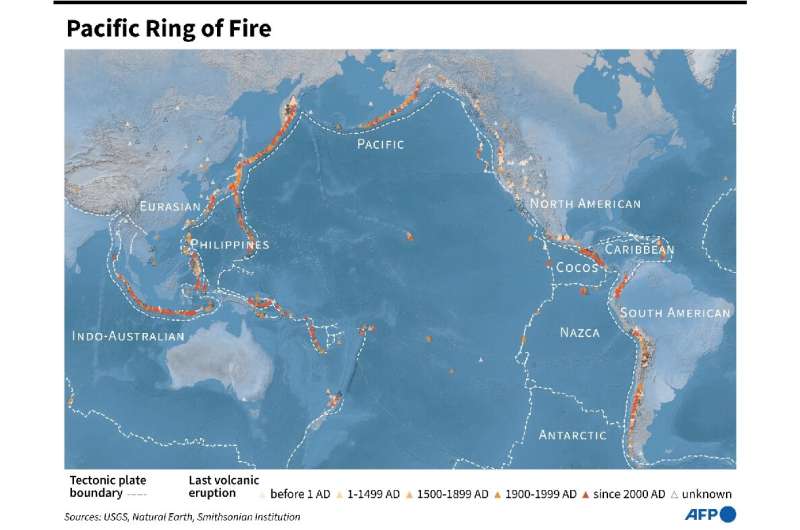

Ring of Fire

Hunga Tonga-Hunga Ha'apai is located in the so-called Ring of Fire, where a rift between shifting tectonic plates results in increased seismic activity.

In a volcanic eruption, magma rising to the surface of the Earth's crust causes volcanic gases to be released that then push their way out from underground, creating pressure.

When the gases reach water it expands into water vapour, creating even more pressure.

Volcano expert Ray Cas of Monash University in Australia said he suspected the intensity of the explosion suggested a large amount of gas had risen into the vent.

"The tsunamis could have been triggered by shock waves propagating through water," he commented on the Australian Science Media Centre.

"But more likely largely by a landslide on the submarine part of the volcanic edifice triggered by the explosive eruption."

Yet another possibility is that the volcano's special location just beneath the surface of the ocean could have made its effects worse.

The volcano's 1,800 metres of height is almost entirely submerged beneath the surface of the ocean, the edge of its crater forming an uninhabited island.

"When eruptions happen deep in the ocean, the water tends to muffle the activity. When it happens in the air, the risks are concentrated to the immediate area," Paris-based geologist Raphael Grandin told AFP.

"But when it's just under the surface, that's when the tsunami risk is greatest," he said.

Exceptionally loud eruption

People are reported to have heard Hunga Tonga-Hunga Ha'apai's eruption as far away as Alaska, 9,000 kilometres from the source, which Grandin said is "exceptional".

"As far as I know the last explosion that was audible at that distance was caused by the Krakatoa volcano in Indonesia in 1883—it killed 36,000 people," he said.

Experts also said that while the volcano could experience further activity, past research shows an eruption of Saturday's scale probably only occurs every 1,000 years.

Scientists who commented on the phenomenon said they would know more about how it took place once communication with the Pacific nation of some 170 islands could be restored.Tongans warned of acid rain after volcanic eruption

© 2022 AFP