LONG READ

AMERICAN libertarian ‘startup city’ in Honduras faces its biggest hurdle: the locals

Próspera was supposed to be a privatized, Silicon Valley-funded paradise — but it's a hard sell for the neighbors.

Villagers on the Honduran island of Roatán thought Próspera was just another resort.

In actuality, it was a whole new city — a libertarian experiment backed by leading Silicon Valley figures.

Próspera’s founders promised to enrich the local community, even supplying water to a nearby village.

But relations with neighboring communities deteriorated. Then, Próspera turned off the taps.

5 OCTOBER 2021

A libertarian ‘startup city’ in Honduras faces its biggest hurdle: the locals

Roatán

The island of Roatán is approximately 65 kilometres off the northern coast of Honduras.

One Friday evening last September, a squad of police officers arrived in Crawfish Rock, a secluded fishing village on the Caribbean island of Roatán, where homes of weather-worn clapboard painted pastel hues perch atop cement pilings.

Sent to break up a public gathering deemed a violation of pandemic restrictions, they found a modest crowd assembled in front of a turquoise house just off the village square. Erick Brimen, a 37-year-old Venezuelan, stood on the raised porch, illuminated by klieg lights, a laptop open on the railing in front of him. He wore work boots, a beige baseball cap, a surgical mask, and a short-sleeved button-down tucked into faded khakis, attire that recalled a suburban construction contractor, which, in a sense, he was.

In 2017, Brimen, who lives in Maryland, secured a plot of land next door to Crawfish Rock. Until recently, many villagers had been under the impression that he and his team were developing some kind of resort. American cruise ships had begun to call at Roatán in the 1990s, and soon, hotels had sprouted along the coastline. The residents of Crawfish Rock welcomed the steady work. Brimen’s development, christened Próspera, broke ground in the spring of 2020, and not long afterward, community leaders were disturbed to learn that the project was far more radical than they had understood. Brimen had called the meeting — against the objections of local leaders — to try to assuage the community’s fears. “You all know that we have not been hiding anything,” he said to the crowd.

Próspera’s founders believe the future of government lies with privatized startup cities. They belong to a movement with deep roots in U.S. libertarian circles: one that wants to redefine citizenship and governance in tech-consumerist terms. It has gained momentum in recent years, as high-profile Silicon Valley figures, like PayPal co-founder Peter Thiel and venture capitalist Marc Andreessen, put their money behind startup city initiatives.

Some governments have been drawn to the idea, too, hoping it will attract foreign investment and spur economic growth. In 2013, Honduras passed a law allowing people like Brimen to set up semi-autonomous, privately run cities, “zonas de empleo y desarrollo económico” (zones for employment and economic development), or “ZEDEs” — pronounced “zeh-dehs.” These cities are to be governed by private investors, who can write their own laws and regulations, design their own court systems, and operate their own police forces. The Honduran government granted Próspera ZEDE status in late 2017. Subject to limited government oversight and few legal restrictions, a set of for-profit firms incorporated abroad by Brimen and his business partners will govern the city — with ambitions to expand across Roatán and onto the Honduran mainland.

Whether these kinds of projects will, as their promoters promise, bring prosperity to local citizens, is far from certain.

Since the 20th century, foreign investors have come to Honduras promising jobs and a higher standard of living. In practice, these arrangements have tended to enrich the foreigners while doing little to deliver on the promised benefits, said José Luis Palma Herrera, a Honduran researcher who has written about ZEDEs.

This year, skeptical Hondurans organized weeks of anti-ZEDE protests across the country. They fear cities like Próspera will leave ordinary people no better off than they were before, while ceding to profit-driven investors the power to decide what’s in the public interest.

In Crawfish Rock, as police climbed the porch stairs towards Brimen, he asked them to step back. Local leaders had asked him not to hold the meeting, citing public health concerns, but he’d pushed ahead regardless. “I am socially distanced,” he said as the officers approached. “I’m not hurting anybody. You might have Covid. Please protect my human rights.”

As police conferred with Brimen’s bodyguards, an officer reached calmly for his microphone. “Excuse me, sir — don’t touch me,” Brimen said, recoiling. One of his bodyguards stepped in and pushed the officer. A scuffle ensued, sending the laptop tumbling to the dirt below. As Brimen called for calm, his bodyguards hustled him down the stairs and out of view.

Brimen’s defiance of local authorities troubled Próspera skeptics. “It was unnecessary and dangerous for him to come and have a meeting,” said Venessa Cárdenas, one of the village leaders who had asked Brimen to postpone his visit. “But he needed something.” What he needed, Cárdenas came to believe, was a chance to create the appearance of engagement with the community, an illusion of transparency. If this was how Próspera’s developers behaved on other people’s turf, what would they be like once they ran the show next door?

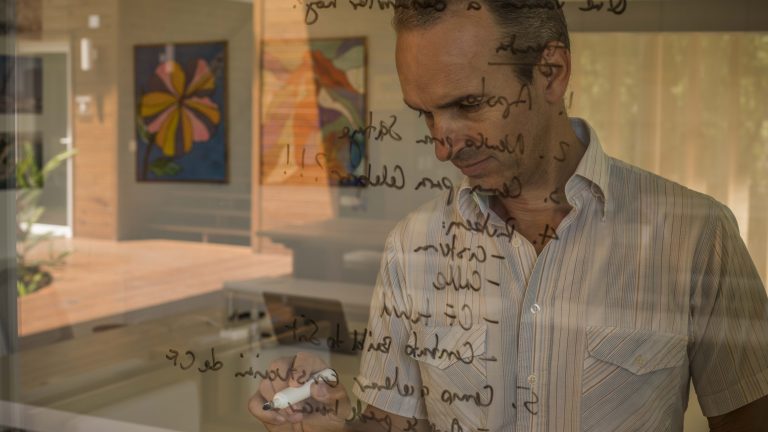

Erick Brimen, co-founder of Próspera, speaks on the phone at a newly acquired section of property on the island in September, 2021.

Erick Brimen grew up in a well-to-do family in Venezuela. In 1998, aged 14, he moved to the U.S. to attend Hargrave Military Academy, in Virginia. Soon after, Hugo Chávez was elected president of Brimen’s home country. At first, he was “captivated by socialism’s promise of a more equal, fair and just society,” as he later wrote in an op-ed for USA Today. He soon grew disillusioned. The “system of free enterprise” he encountered as a high schooler in the United States, he wrote, “stood in stark contrast to the growing poverty, stagnation and despair in my homeland.”

After graduating from the business-focused Babson College in Massachusetts in 2006, he pursued a fairly conventional career in finance and consulting, before striking out on his own and founding two small tech companies. In 2014, he joined an initiative at Babson College, aimed at using startup cities to foster entrepreneurship in emerging economies. Brimen’s role was to help secure financing for these projects via NeWay Capital, an investment fund that he had incorporated with the tagline: “investing to alleviate poverty profitably.” The Babson initiative eventually fizzled out — a result of internal politics at the school, Brimen says — but by then, his work had introduced him to the Honduran ZEDE law.

Soon, he was a convert. In an address to a 2016 tech-libertarian conference in Austin, Texas, he explained he’d come to see poverty as essentially an antitrust problem. What government offered was simply “a basket of services,” he told his audience, “provided in a bundle for a fixed price by a single provider.” If competition and profit motive improve the quality of commercial services, couldn’t they do the same for government services?

In Guatemala, tech entrepreneur Gabriel Delgado had come to similar conclusions. Delgado was born into a family of committed economic libertarians. His grandfather founded Universidad Francisco Marroquín in Guatemala City, whose façade boasts a massive brass relief commemorating Ayn Rand’s Atlas Shrugged.

Like Brimen, Delgado attended college in the United States, at Trinity University, in Texas. Back in Guatemala, Delgado helped found startups operating in a range of tech segments—IT security, vehicle fleet logistics, mobile app development, cryptocurrency — but he grew frustrated by the corruption. Rebuff the inevitable request for a bribe, and your paperwork would hit mysterious snags, resulting in long delays.

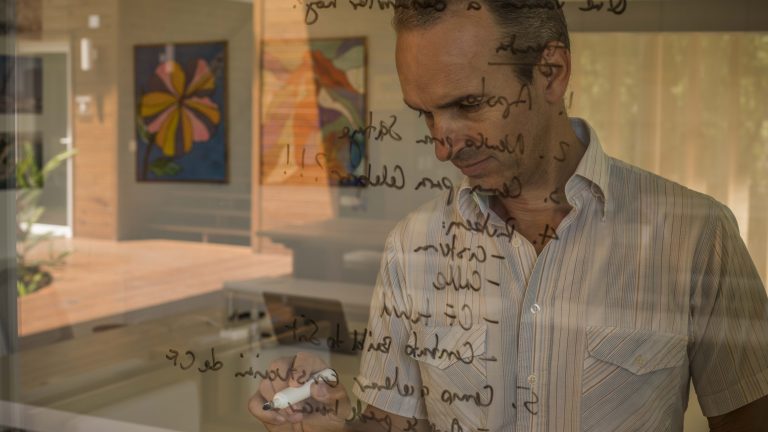

Gabriel Delgado, co-founder of Próspera, explains plans for the project in a building on the site in September, 2021.

Delgado joined a group seeking national-level government reform in Guatemala, ProReforma, but he found the endeavor Sisyphean. “For a long time, I said, ‘Okay, if we choose the right politician, then things are going to change,’ but that doesn’t work,” he told Rest of World over lunch earlier this year. “Any reforms that are made that are good are rolled back by the cronies. … A group of us decided that what we needed to change was not the driver, but we needed to change the vehicle we were driving in.”

Startup cities struck him as a more manageable space for smaller-scale experimentation with new modes of governance, and they appealed to his tech background and preference for laissez-faire policy.

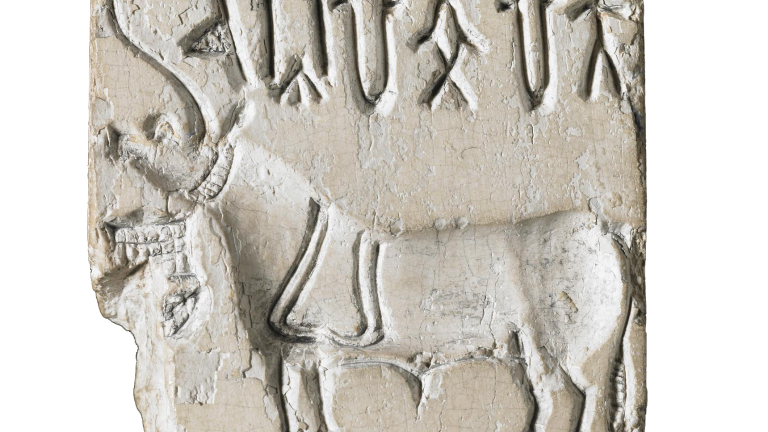

Delgado had been drawn to Honduras during an earlier flirtation with startup cities in the country — the 2011 “charter cities” initiative, the brainchild of the American economist and Nobel laureate Paul Romer. Romer’s idea was that governments of advanced economies should build and govern new cities in emerging economies, modelling good governance practices for the hosts, while attracting foreign investors.

The Honduran charter city initiative fell apart in the fall of 2012. A few weeks before the Honduran Supreme Court ruled it unconstitutional, Romer resigned from the program, citing a lack of transparency. He had been dismayed, he wrote at the time, to learn that the government had signed a secret agreement with a consortium of investors — Delgado among them — who intended to start a charter city administered not by a foreign government but as a private for-profit enterprise.

“We’ve both experienced—though he’s experienced it more poignantly than me—how you can lose your country.”

The ZEDE law emerged from the wreckage. Enacted in 2013, it replaced the government-centered vision advanced by Romer, who has criticized the ZEDE model, with a private sector–driven approach favored by Delgado and his fellow investors. The ZEDE oversight committee was packed with libertarian figures, including the U.S. anti-tax fundamentalist Grover Norquist and one of Ronald Reagan’s sons, Michael.

In 2014, Delgado assembled a new group of investors. The universe of prospective ZEDE founders was small, and Delgado soon heard that Brimen, still at the Babson Initiative, was looking into investing in a Honduran ZEDE. Delgado reached out. The two men bonded over their common histories. “We’ve both experienced—though he’s experienced it more poignantly than me—how you can lose your country,” Delgado said.

By the middle of 2017, with the Babson initiative out of the picture, the nature of the conversation shifted. Brimen was interested in a more hands-on role than that of a mere financier, and the two joined forces. They complemented one another in useful ways. Delgado, who is in his 50s but retains the wiry frame of a long-distance runner, is a big-picture guy and possesses a pitchman’s free-wheeling enthusiasm. Brimen, meanwhile, is detail-oriented and, in conversation, tends toward the dour precision of an engineer.

The pair were drawn to Roatán by Tristan Monterroso, an evangelical pastor from the island who had attended military school with Brimen and had long agitated for his old friend to invest there.

With Monterroso’s help, they scouted locations across the island before deciding to buy the 23.5 hectares next to Crawfish Rock, which would give them a chance to prove their concept. Earlier this year, over espresso at a Roatán resort, Brimen recalled the thought process. “This is a poor community with some substantial shortfalls in service,” he told Rest of World. “It’s big enough where it’s a challenge, but it’s small enough where, given the size of our planned investments, we can really make a difference.”

Workers in Próspera’s “Beta Building” on the island of Roatán.

One morning earlier this year, Brimen met a pair of reporters from Rest of World in the parking lot of the Megaplaza shopping mall on Roatán, to take them on a tour of Próspera. Brimen had traded his construction-contractor outfit for a dad-on-safari look: olive green Columbia fishing shirt—a status brand among Honduran elites — khakis that unzipped into cargo shorts, and photochromic glasses.

Brimen’s SUV audibly struggled as it navigated the deep ruts and roller-coaster contours of the Crawfish Rock Road, dust billowing in its wake. At the turnoff for Próspera, a security guard, sidearm on his hip, emerged from a wooden shack and — whether for show or not — checked Brimen’s ID. A large sign beside the guard shack read, “Providing running water since September 2019.”

Further along, the dense roadside foliage gave way, opening onto a clearing. Próspera hopes to host medical and education complexes, a financial center, a shopping district, resorts, and hotels. Only a handful of buildings were close to completion, but if all goes according to plan, Próspera will grow from a 23.5-hectare village to a full-fledged city over the next decade.

Próspera raised $10 million in its latest funding round — twice its goal — from 30 investors, according to Brimen. Among its backers is Pronomos Capital, a venture-capital fund that, per its website, draws on “the lessons of Silicon Valley to create a new model for urban development where the city is the product.” It’s run by Patri Friedman, grandson of the economist Milton, and bankrolled by, among others, Peter Thiel.

In Próspera’s next investment round, Brimen says, his team plans to raise an additional $30 million. That still falls far short of the capital investment needed to build a city that aims to host thousands of residents by 2025, but Próspera expects real estate firms will stump up the rest of the cash. To date, the ZEDE has found one such investor, a small Honduran company called Apolo Group, which, in July, agreed to build a single mixed-use residential high rise.

Workers of foreign companies hosted at Próspera take a lunch break.

Applications for residency require a background check, a Honduran residency permit, and an annual fee — $260 per year for Hondurans and $1,300 for foreigners. Prospective residents will also have to sign something called an “agreement of coexistence,” which lays out all the rights and responsibilities of Próspera residents and Próspera’s obligations to them. Brimen characterized it as, “if you could make the social contract a real contract.” The agreement incorporates Próspera’s resident bill of rights, which is modeled on the U.S. Bill of Rights but with some decidedly libertarian twists.

Government services will be centralized and automated through ePróspera, an online portal modeled on the much-praised e-Estonia system developed by the Baltic nation. From the comfort of their homes, Prósperans will be able to pay taxes, incorporate a company, transact business, and even buy real estate. They’ll be able to vote, too, but their franchise is limited. Residents elect only five of the council’s nine members. Landowners vote for two of the five, with voting power pegged to acreage. Buy more land, buy more votes. Próspera’s founders choose the four remaining council members, and a six-member supermajority is needed to alter policy.

A SimCity-esque “Configurator” — a nod to Tesla’s car-design interface — lets residents select an exterior design and lay out the interior of apartments before making a purchase. There are plans to log real estate transactions on a blockchain ledger. The architecture firm Zaha Hadid Architects is working with Próspera to design its look, and digital renderings hew to the neofuturist style for which the firm is known.

Próspera’s ambitions extend far beyond its present stretch of Roatán coastline. Brimen and Delgado envision an archipelago of “Prosperity Hubs” across Roatán and the mainland, startup-city protectorates of Próspera’s metropole, with interhub transport via aerial drone taxi. (In 2020, Próspera authorized the creation of the first Prosperity Hub outside Roatán, in the Honduran fruit export hub of La Ceiba.)

The Beach Club of Pristine Bay in September, 2021.

The resort, and nearby land was recently acquired as part of Próspera.

Embedded in the fine print and legalese of investor documents and governing statutes resides the makings of a radical experiment in laissez-faire governance. Government services will be provided entirely by a contractor, an idea borrowed from the Atlanta suburb of Sandy Springs. In 2005, the town sought to cut costs by privatizing everything from policing to street sweeping, and, for libertarians, it’s proof of concept for outsourcing bureaucracy. Oliver Porter, who created the Sandy Springs model, sits on Próspera’s board of directors and governing council.

Effective tax rates will sit in the low single digits, and, in place of Honduran courts, there’s a private arbitration center. But where the business inducements enter unprecedented terrain is health and safety regulation. Próspera won’t impose rules so much as curate prix fixe and à la carte menus of rules. Companies will be able to opt into an existing regulatory regime — choosing from dozens of countries and U.S. states — or they can Frankenstein together an entirely novel code, mixing and matching rules from different jurisdictions and even inventing new ones. The building code for one new construction at Próspera, Delgado told Rest of World by way of example, is a pastiche of Honduran and U.S. law. The lone requirements: sign-off by Próspera’s governing council and a liability insurance policy, most likely underwritten, Delgado says, by offshore insurers.

Próspera’s hands-off regulatory philosophy has caught the attention of the medical tourism industry. Delgado has held talks with a controversial gene-therapy startup, Minicircle, to open a clinic in Próspera. It will be funded by a “network of crypto investors,” according to its CEO, Machiavelli Davis. Davis runs in biohacking circles, a set best known for self-administering untested gene therapies. Próspera appeals to him in part because it purports to authorize clinical testing at a far earlier stage than American regulators allow, as long as test subjects give informed consent.

Brimen believes that Próspera’s genius stems from the link between investor returns and social aims. “We have effectively created a business model that provides a profit to investors as a result of creating generalized prosperity,” he said. Policies that boost resident incomes will enlarge tax revenue for Próspera, which will yield larger dividends for investors — incentives elegantly aligned. That’s the theory anyway.

Children from Crawfish Rock walk along the beach near their village.

Venessa Cárdenas lives near the dusty terminus of the Crawfish Rock Road. From her raised porch, she can keep an eye on the moods of the Caribbean, most often impassive, stilled by the Great Mayan Reef, just offshore.

Cárdenas said she first met Brimen in late 2017, when he and some business partners were out greeting their new neighbors. Like many villagers, she believed Próspera was just another resort, though, as time passed, she found it odd that the real estate developers kept a near-continuous presence in Crawfish Rock.

A foundation, then called the Institute for Excellence, run by Monterroso, rented a turquoise house by the village square — the site of Brimen’s later encounter with police — and began to undertake philanthropic projects in the village: small-business loans, carpentry workshops, and after-school programs. Soon, Próspera’s social media feeds and promotional materials swelled with photographs of the foundation’s good works.

In the summer of 2019, after issues with its cistern led Crawfish Rock to lose access to running water, Próspera connected the village to its own water tank. The villagers were grateful. But some villagers were surprised when water bills arrived. Stranger still, monthly payments went to the Institute for Excellence. Why, they wondered, was a charitable foundation acting like a water utility? Brimen would later explain that, in general, Próspera doesn’t “believe in charity as a primary source of support, because I think it creates dependencies.” But dependency, Cárdenas would come to suspect, was exactly what this was all about.

This wasn’t the first time Próspera had insinuated itself into life in Crawfish Rock. In Honduras, patronatos are hyperlocal councils empowered to speak on behalf of their communities. In June 2019, Próspera arranged for villagers to elect a new patronato. Monterroso handpicked a slate of candidates, who ran uncontested.

In May 2020, just after Próspera broke ground, its relationship with Crawfish Rock started to unravel. There were protests over the fact that few construction jobs went to villagers and an outcry after Próspera’s armed security guards, responding to a spate of robberies, began asking people coming and going from Crawfish Rock to identify themselves and state their business. On Próspera’s website, Cárdenas found sketches of its future footprint. Although hard to tell, it looked worryingly like the ZEDE planned to absorb Crawfish Rock, and some villagers worried that Próspera officials would ask the Honduran government to expropriate their land on the ZEDE’s behalf. At best, as Próspera grew, it would cut off Crawfish Rock from the rest of the island, pinning it against the sea.

In June 2020, Brimen, who was stuck in the U.S. due to Covid travel restrictions, sent villagers an almost hour-long voice message over WhatsApp. Próspera would never seek or accept expropriated land, he said. Brimen cataloged all that Próspera’s foundation had done for Crawfish Rock, finally turning to the water supply, for which Próspera had agreed to stop billing during the pandemic. His tone veered from disappointment to veiled threats. “Wow,” he said, in a breathy whisper of faux-astonishment, “how terrible, eh? To live in this modern age and lack running water.” He went on: “Running water to your home, such a basic yet transformative and essential service.” A pause for effect. “Who did that?”

Venessa Cárdenas, one of the village leaders, at her home in Crawfish Rock.

The following month, Brimen flew to Roatán. Several civil society groups had issued a statement criticizing Próspera’s treatment of Crawfish Rock, and he wanted the patronato to disavow it on the village’s behalf. But before that could happen, villagers opposed to the ZEDE called for a new vote, one not orchestrated by Próspera. Though only in her 30s, Cárdenas, now a leader of Crawfish Rock’s opposition to Próspera, was elected vice-president, and her friend Luisa Connor became president.

Throughout early September, Covid-19 cases surged on Roatán. After learning that Brimen planned to hold a public meeting to address community concerns, the new patronato sent him a letter, civil in tone, asking him to postpone the event. “We are open to dialog,” the letter read, “in hopes of a favorable solution, for all parties.” Brimen reacted furiously in a voice message sent to Cárdenas’ mother. He demanded the patronato retract its letter, which he characterized as an assault on free speech and the right to assemble. “They can end up in jail if they keep up this type of behavior,” he said.

Brimen held the meeting that evening in front of the turquoise house in Crawfish Rock — at least until the police shut it down. Cárdenas saw the performance at the public meeting as a PR stunt—the klieg lights, the porch-turned-pulpit. She believes Brimen wanted an incontrovertible record of him engaging with transparency and candor to undermine villagers’ claims that Próspera hadn’t been forthcoming. If so, it backfired. Brimen’s encounter with the police made the rounds on social media and even the local news, only adding to Próspera’s image problem.

In late October, Cárdenas and Connor received an unsigned letter from the Próspera Foundation, a new name for the charitable organization Monterroso oversees. The foundation had heard that the pair were looking at ways of restoring Crawfish Rock’s old water supply. The letter said that the foundation assumed that meant they no longer wanted to access water from the ZEDE’s well, and was going to cut them off in 30 days’ time.

There was only one way to keep the water flowing, the letter concluded — the patronato had to ask for it “in writing on behalf of the community.” A second letter went out at the same time, this one a notice, from Próspera to villagers across Crawfish Rock, alerting them that they would lose water service in 30 days. Próspera placed the blame squarely on the patronato. “The current leaders do not want the community to have access to Próspera-ZEDE sourced water,” the letter claimed, repeating — in a bolded and underlined passage — the ultimatum Cárdenas and Connor had received. If the patronato made a request in writing, the pipes would remain open.

Cárdenas saw it as a divide-and-conquer tactic. The patronato had never asked Próspera to shut off the water, and its members didn’t want the community to go without while they worked to get the old water system online again. But given all that had happened, they refused to sign anything Próspera could spin as proof that the ZEDE had the village’s blessing. A month later, the taps in Crawfish Rock ran dry.

Water distribution in Crawfish Rock in September, 2021. Since the local well ran dry, families have had to buy water by the barrel from a delivery service.

On a Saturday in mid-January 2021, Ron McNab, an outgoing congressman and a candidate for mayor of Roatán, held a campaign rally in Crawfish Rock. The air was damp and heavy. Languorous clouds idled over gray seas, contemplating rain. A sizable crowd had turned out in the village square nevertheless. Eventually, a calypso-tinged campaign anthem began to pulse from the speakers near the pulperia. The song had the earworm quality of an ad jingle and an impressively succinct refrain, “Vamos con Ron, Ron McNab. / Vote for Ron, Ron McNab.”

Before Brimen’s encounter with the police, local political leaders had generally supported Próspera or remained silent on the issue. Afterward, sensing, perhaps, that the winds were beginning to change, they took to denouncing the ZEDE. “I think we’ve made it very clear,” McNab told the crowd, “but I’m going to say it again: we do not support the ZEDE or Próspera.”

After Próspera had cut off Crawfish Rock, the patronato had enlisted McNab’s help to restart their old cistern. Cárdenas, who was in the audience, was grateful not to be beholden, for such a basic need, to people she didn’t trust. “We got the water, and it’s ours,” she said. “Crawfish Rock water.”

A little way up the Crawfish Rock Road, the sign at the turnoff to Próspera still read, “Providing running water since September 2019.”

Getting the water supply fixed was a rare example of the government doing what it’s supposed to. Corruption suffuses Honduras’ politics and institutions. Given their own experiences in their home countries, it’s understandable that Brimen and Delgado are skeptical of big government. What Próspera promises — “empirical-evidence driven” strategies to replicate “tested solutions,” “best practices,” and policies “proven” to maximize prosperity, according to its two founders — is seductive. But the evidence they point to to support their case doesn’t stand up to scrutiny.

In 2019, the city council in Sandy Springs, the Atlanta suburb that privatized almost all of its government services in 2005, voted to bring nearly all of that contract work in-house again. Outsourcing proved to be more, not less, expensive. Nor is there any antecedent for a system of bespoke regulation that assigns offshore insurance companies the role of de facto regulator. Even some of Próspera’s boosters, like Mark Lutter, who founded and runs the nonprofit Charter Cities Institute, doubt whether it makes sense to ask a retired state judge from Arizona — three of the Próspera Arbitration Center’s seven arbiters match this description — to decide a case that turns on a hodgepodge of, say, Honduran, French, and Japanese regulations.

A central tenet of the startup city movement is the promise of letting people vote with their feet. For Brimen and his cohort — well-off, educated, peripatetic — this idea holds purchase. Don’t like one startup city? Find one that better suits your preferences. But this global mobility is a luxury of the well-to-do and the cosmopolitan, and not everybody affected by Próspera will live within the ZEDE. There are lots of people in Crawfish Rock, for example, who never opted into a future where their ancestral home is all but immured by a gated community engaged in controversial forms of social and political experimentation.

Toward the end of his stump speech, McNab, whose family has lived on Roatán for generations, paused to ruminate on the nature of place and identity. “This island is our home, and it’s the oldest place we’ve got,” he said. “It’s not as if I can pick up and go back to Olancho or Olanchito [on the mainland] if things go south on Roatán. Ain’t nowhere for me to go.” In the audience, Cárdenas nodded and repeated the word “nowhere.”