It’s possible that I shall make an ass of myself. But in that case one can always get out of it with a little dialectic. I have, of course, so worded my proposition as to be right either way (K.Marx, Letter to F.Engels on the Indian Mutiny)

Monday, March 14, 2022

Fleeing Putin’s wartime crackdown, Russian journalists build media hubs in exile

By Steve Hendrix

Today

The Washington Post

VILNIUS, Lithuania — Sergey Smirnov sat on the floor of a dark and dirty Airbnb, leading an editorial meeting of the Russian news organization that continues to work even as he and his staff are on the run from the Kremlin’s crackdown on a free press.

Smirnov, the editor in chief of Mediazona, was in an apartment above a fried chicken restaurant in this Baltic capital, surrounded by two dogs and the half-dozen stuffed shopping bags he was able to fling into his car on March 4. That was the day Russian President Vladimir Putin approved draconian prison terms for journalists who stray from Kremlin propaganda. Smirnov’s wife and two sons, including a 4-week-old newborn, remain in Moscow.

The 22 Mediazona reporters on the Zoom call were in Tbilisi, Prague, Istanbul — whatever city they could reach after international sanctions dried up flights from Moscow and rendered their Russian credit cards useless at gas stations around Europe. Where to get visas, apartments, funding, sympathy — these are the challenges they face in an unprecedented exodus of journalists from their homeland.

“I wonder if we should do a story on the hostility Russians are feeling in other countries,” one of the tired faces on Smirnov’s screen said. Another reporter agreed, while a third was hesitant.

Smirnov, who has already been imprisoned for his reporting in Moscow, shook his head. “We are facing difficulties, but it is nothing compared to what they are going through in Ukraine.”

The media clampdown in Russia that followed the invasion of Ukraine has decimated a journalism community already ground to near extinction by years of oppression. The New York-based Committee to Protect Journalists said at least 150 of Russia’s few remaining independent reporters and editors have left since tanks rolled into Ukraine, plunging Russia into what the group called an “information dark age.”

Now — in Lithuania, Latvia, Georgia and other former Soviet states where Russian remains a common language — they are scrambling to set up newsrooms in exile, determined to continue the hazardous mission of speaking truth to authoritarianism.

“They are going to need to rebuild the infrastructure outside of Russia, and that won’t be easy,” said Vytis Jurkonis, Lithuania director at Freedom House, the pro-democracy watchdog based in Washington.

The immediate need, before any newsrooms or studios are built, is to get journalists and their families residency permits, housing, schools and ways to keep reporting.

“The logistics are hard,” Jurkonis said. “But they need to go do their work and not lose their audience. That’s what the Kremlin wants, to separate these critical journalists from their audience.”

Already, in shared hotel rooms or on friends’ couches, reporters are exploring ways to stay in touch with sources in Russia. Those who arrived earlier are schooling newcomers on the cloaking advantages of VPNs (virtual private networks), encrypted text apps and the chat functions of online video games.

On Sunday, Mediazona published multiple stories on police actions against antiwar protests in St. Petersburg, Russia’s second-largest city.

Putin’s prewar moves against U.S. tech giants laid groundwork for crackdown on free expression

Dmitry Semenov, who escaped to Lithuania after being indicted for his writing and activism four years ago, is hearing every day from journalists suddenly on the run, wanting to know where they should go and how to do their jobs when they get there.

“Right now, any escape from Russia is good; any city you get to is better than staying inside the country,” said Semenov, who now reports for Lithuanian television and speaks every day with fleeing journalists — including from Radio Free Europe and Rain, the main independent TV network in Russia — about relocating to Lithuania.

Many have already arrived in the small but hospitable outpost of Vilnius, a city of medieval streets and half a million residents with a history of protecting human rights activists. Vilnius has emerged as a hub of dissidents and persecuted politicians escaping Putin’s reach, including a team that supports imprisoned Russian opposition leader Alexei Navalny. Exiled Belarusian presidential candidate Svetlana Tikhanovskaya also decamped to Vilnius in 2020.

Russian journalists say they feel welcome here, but the city is not without intrigue. In 2021, security agents were able to snatch Belarusian blogger Roman Protasevich, who was living in Lithuania, by having his flight to Vilnius diverted to Minsk with a fake bomb threat.

Last week, Lithuania’s state security service warned the swelling ranks of exiles in the city that Russian and Belarusian agents were becoming more aggressive here. In a Facebook post, it cautioned journalists to be alert for attempts to hack their devices and infiltrate their social circles.

“I don’t think the journalists should concentrate in any one country,” Jurkonis said. “It will make them easy targets for Russian operatives.”

For now, reporters are still recovering from their pell-mell flight from Russia. Just days ago, Olesia Ostapchuk was writing about Russian mothers who had lost their sons in Ukraine for the independent outlet Holod. After a new law threatened journalists with 15 years in prison for describing Russia’s war on Ukraine as a “war,” she headed for the airport.

It took two days of canceled flights before she finally landed in the western Russian city of Kaliningrad, allowing her to pull her 80-pound pink suitcase across the bridge to Lithuania.

“I left most of my clothes, my books, everything,” said Ostapchuk, 24. “Also my boyfriend and my family.”

She only told her grandmother, a Putin supporter who wasn’t fully aware of Ostapchuk’s journalism, that she was going on a business trip. She doesn’t know if she will ever see her again. She has relatives in Ukraine to worry about as well.

For Smirnov, the need to flee was not unexpected. One of Russia’s most esteemed independent journalists, he has run Mediazona since it was founded in 2014 by one of the members of Pussy Riot, the dissident punk band. The organization focuses on Russia’s criminal justice system and is known for liveblogging from the show trials against activists and politicians.

“Even before now, they faced political danger that most of us can’t even imagine,” said Carroll Bogert, president of the New York-based Marshall Project, upon which Mediazona was modeled.

Last year, Russian officials forced Mediazona and Smirnov to register under the restrictive “Foreign Agents” law, deeming that money generated by Google ads on its website amounted to international funding. Smirnov was also imprisoned for 25 days for retweeting a joke that offended the Kremlin.

He experimented with reporting from Georgia for a few months in 2021, but returned to Moscow after finding Tbilisi “too relaxing.”

“It’s not normal, but you get used to waking up at night each time you hear the elevator door open,” he said. “You feel the tension to understand the tension.”

Still, he kept a bag packed, cash on hand, passports ready and prepared veterinarian documents for his dachshund with a heart condition. When the new prison terms were announced, he loaded his green Kia Soul for the 27-hour sleepless drive to Vilnius, including a 13-hour wait at the border.

A few days later, Mediazona and numerous other independent sites were blocked by the Russian government for violating the new restrictions.

“I’m ready to go to prison for two years, but 15? No,” he said.

Smirnov’s son, born in February, doesn’t have travel documents yet. He hopes his family will join him in Vilnius in a few months, hopefully in better accommodations than the dank studio flat with the oversized hot tub that was all he could find.

“The apartments are all gone and I’m not a desirable renter, a Russian with two dogs,” he said.

Mediazona was getting about $50,000 a month through online donations, most from inside Russia. Those funds are gone now, along with most of the company cash that was in Russian banks. Smirnov’s immediate goals are to get the rest of his people out of Russia — he’s paying for their transport and a month’s rent wherever they are — and to keep the journalism going.

“We can’t even plan our future yet,” Smirnov said as he carried his ailing pet to the elevator for a bathroom break outside. “It’s still too crazy.”

Arturas Morozovas contributed to this report.

By Steve Hendrix

Today

The Washington Post

VILNIUS, Lithuania — Sergey Smirnov sat on the floor of a dark and dirty Airbnb, leading an editorial meeting of the Russian news organization that continues to work even as he and his staff are on the run from the Kremlin’s crackdown on a free press.

Smirnov, the editor in chief of Mediazona, was in an apartment above a fried chicken restaurant in this Baltic capital, surrounded by two dogs and the half-dozen stuffed shopping bags he was able to fling into his car on March 4. That was the day Russian President Vladimir Putin approved draconian prison terms for journalists who stray from Kremlin propaganda. Smirnov’s wife and two sons, including a 4-week-old newborn, remain in Moscow.

The 22 Mediazona reporters on the Zoom call were in Tbilisi, Prague, Istanbul — whatever city they could reach after international sanctions dried up flights from Moscow and rendered their Russian credit cards useless at gas stations around Europe. Where to get visas, apartments, funding, sympathy — these are the challenges they face in an unprecedented exodus of journalists from their homeland.

“I wonder if we should do a story on the hostility Russians are feeling in other countries,” one of the tired faces on Smirnov’s screen said. Another reporter agreed, while a third was hesitant.

Smirnov, who has already been imprisoned for his reporting in Moscow, shook his head. “We are facing difficulties, but it is nothing compared to what they are going through in Ukraine.”

The media clampdown in Russia that followed the invasion of Ukraine has decimated a journalism community already ground to near extinction by years of oppression. The New York-based Committee to Protect Journalists said at least 150 of Russia’s few remaining independent reporters and editors have left since tanks rolled into Ukraine, plunging Russia into what the group called an “information dark age.”

Now — in Lithuania, Latvia, Georgia and other former Soviet states where Russian remains a common language — they are scrambling to set up newsrooms in exile, determined to continue the hazardous mission of speaking truth to authoritarianism.

“They are going to need to rebuild the infrastructure outside of Russia, and that won’t be easy,” said Vytis Jurkonis, Lithuania director at Freedom House, the pro-democracy watchdog based in Washington.

The immediate need, before any newsrooms or studios are built, is to get journalists and their families residency permits, housing, schools and ways to keep reporting.

“The logistics are hard,” Jurkonis said. “But they need to go do their work and not lose their audience. That’s what the Kremlin wants, to separate these critical journalists from their audience.”

Already, in shared hotel rooms or on friends’ couches, reporters are exploring ways to stay in touch with sources in Russia. Those who arrived earlier are schooling newcomers on the cloaking advantages of VPNs (virtual private networks), encrypted text apps and the chat functions of online video games.

On Sunday, Mediazona published multiple stories on police actions against antiwar protests in St. Petersburg, Russia’s second-largest city.

Putin’s prewar moves against U.S. tech giants laid groundwork for crackdown on free expression

Dmitry Semenov, who escaped to Lithuania after being indicted for his writing and activism four years ago, is hearing every day from journalists suddenly on the run, wanting to know where they should go and how to do their jobs when they get there.

“Right now, any escape from Russia is good; any city you get to is better than staying inside the country,” said Semenov, who now reports for Lithuanian television and speaks every day with fleeing journalists — including from Radio Free Europe and Rain, the main independent TV network in Russia — about relocating to Lithuania.

Many have already arrived in the small but hospitable outpost of Vilnius, a city of medieval streets and half a million residents with a history of protecting human rights activists. Vilnius has emerged as a hub of dissidents and persecuted politicians escaping Putin’s reach, including a team that supports imprisoned Russian opposition leader Alexei Navalny. Exiled Belarusian presidential candidate Svetlana Tikhanovskaya also decamped to Vilnius in 2020.

Russian journalists say they feel welcome here, but the city is not without intrigue. In 2021, security agents were able to snatch Belarusian blogger Roman Protasevich, who was living in Lithuania, by having his flight to Vilnius diverted to Minsk with a fake bomb threat.

Last week, Lithuania’s state security service warned the swelling ranks of exiles in the city that Russian and Belarusian agents were becoming more aggressive here. In a Facebook post, it cautioned journalists to be alert for attempts to hack their devices and infiltrate their social circles.

“I don’t think the journalists should concentrate in any one country,” Jurkonis said. “It will make them easy targets for Russian operatives.”

For now, reporters are still recovering from their pell-mell flight from Russia. Just days ago, Olesia Ostapchuk was writing about Russian mothers who had lost their sons in Ukraine for the independent outlet Holod. After a new law threatened journalists with 15 years in prison for describing Russia’s war on Ukraine as a “war,” she headed for the airport.

It took two days of canceled flights before she finally landed in the western Russian city of Kaliningrad, allowing her to pull her 80-pound pink suitcase across the bridge to Lithuania.

“I left most of my clothes, my books, everything,” said Ostapchuk, 24. “Also my boyfriend and my family.”

She only told her grandmother, a Putin supporter who wasn’t fully aware of Ostapchuk’s journalism, that she was going on a business trip. She doesn’t know if she will ever see her again. She has relatives in Ukraine to worry about as well.

For Smirnov, the need to flee was not unexpected. One of Russia’s most esteemed independent journalists, he has run Mediazona since it was founded in 2014 by one of the members of Pussy Riot, the dissident punk band. The organization focuses on Russia’s criminal justice system and is known for liveblogging from the show trials against activists and politicians.

“Even before now, they faced political danger that most of us can’t even imagine,” said Carroll Bogert, president of the New York-based Marshall Project, upon which Mediazona was modeled.

Last year, Russian officials forced Mediazona and Smirnov to register under the restrictive “Foreign Agents” law, deeming that money generated by Google ads on its website amounted to international funding. Smirnov was also imprisoned for 25 days for retweeting a joke that offended the Kremlin.

He experimented with reporting from Georgia for a few months in 2021, but returned to Moscow after finding Tbilisi “too relaxing.”

“It’s not normal, but you get used to waking up at night each time you hear the elevator door open,” he said. “You feel the tension to understand the tension.”

Still, he kept a bag packed, cash on hand, passports ready and prepared veterinarian documents for his dachshund with a heart condition. When the new prison terms were announced, he loaded his green Kia Soul for the 27-hour sleepless drive to Vilnius, including a 13-hour wait at the border.

A few days later, Mediazona and numerous other independent sites were blocked by the Russian government for violating the new restrictions.

“I’m ready to go to prison for two years, but 15? No,” he said.

Smirnov’s son, born in February, doesn’t have travel documents yet. He hopes his family will join him in Vilnius in a few months, hopefully in better accommodations than the dank studio flat with the oversized hot tub that was all he could find.

“The apartments are all gone and I’m not a desirable renter, a Russian with two dogs,” he said.

Mediazona was getting about $50,000 a month through online donations, most from inside Russia. Those funds are gone now, along with most of the company cash that was in Russian banks. Smirnov’s immediate goals are to get the rest of his people out of Russia — he’s paying for their transport and a month’s rent wherever they are — and to keep the journalism going.

“We can’t even plan our future yet,” Smirnov said as he carried his ailing pet to the elevator for a bathroom break outside. “It’s still too crazy.”

Arturas Morozovas contributed to this report.

13 March 2022artillery rocket, cluster bomb, cluster munition, cluster munitions, indirect fire, MBRL, rockets, Russia, submunition, submunitions, Ukraine

N.R. Jenzen-Jones & Patrick Senft

Editor’s Note: This article is based primarily on previous ARES article documenting the use of the N235 submunition in Syria and Ukraine in 2014.

Numerous photos posted on Twitter by the State Emergency Service of Ukraine (DSNS), Kharkiv Region, and others show munitions marked in Cyrillic “9H235” (‘9N235’) that have been employed by Russian forces in Ukraine. These markings identify the munitions as Russian 9N235 submunitions, indicate that the submunitions used in this attack were manufactured in 2019, and provide additional lot/batch information that may be helpful in future analysis.

The 9N235 submunition is a high explosive fragmentation (HE-FRAG) submunition designed to engage both personnel and unarmored vehicles in open terrain or behind light cover. The body of the 9N235 is cylindrical in form, measuring 263 mm in length and 65 mm in diameter. Each 9N235 features six spring-loaded fins, which open after separation from the carrier munition to orient the submunition such that its nose—fitted with the 9E272 impact fuze—strikes the ground first. The 9E272 impact fuze is paired with a self-destruct mechanism that is designed to function 110 seconds after ejection from the cargo rocket. 9N235 submunitions contain 312 g of what is believed to be A-IX-10 explosive composition, consisting of 95% RDX phlematigsed by the addition of 5% paraffin wax. The submunition contains pre-formed fragmentation consisting of pieces of chopped steel rods. These are of two sizes: the smaller fragments (nominally weighing 0.75 g) are mainly intended to injure and kill personnel, whereas the larger fragments (nominally 4.5 g) are intended to damage lightly armoured vehicles and materiel. Each 9N235 contains approximately 96 4.5 g fragments and 360 0.75 g fragments.

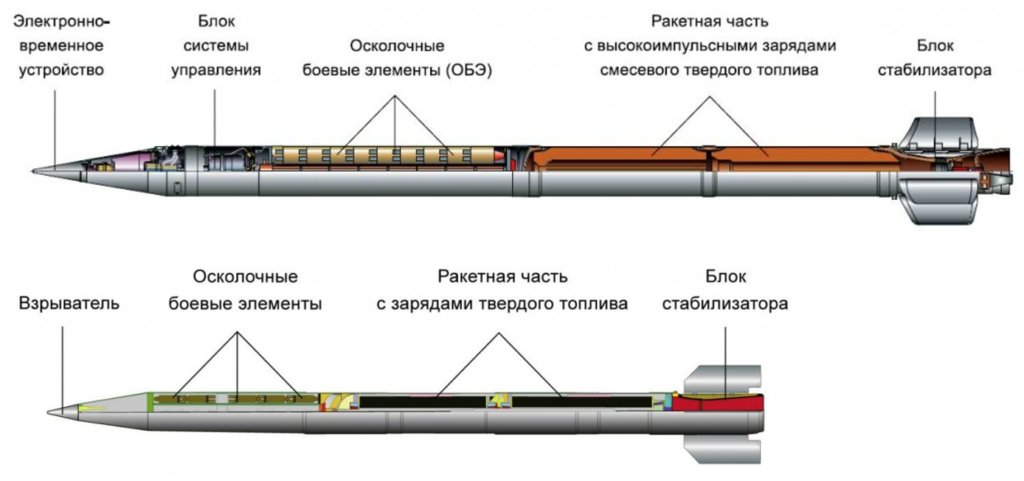

From the available imagery described, it is unclear how the 9N235 submunitions were delivered in this particular incident. However, in the ongoing war in Ukraine, ARES has identified 9N235 submunitions delivered by both the 300 mm 9M55K and the 220 mm 9M27K1 cargo rockets. The 300 mm 9M55K cargo rocket is fired by the 9K58 Smerch (Смерч; ‘Tornado’) multiple-barrel rocket launcher (MBRL). The 9K58 MBRL system was initially designed in the USSR and its unguided rockets can be readily identified by their distinctive nose cones and tail fins, and by an analysis of internal frame and separation components. When carrying 9N235 fragmentation submunitions, the 9M55K rocket has a range of 20 to 70 km and can deliver 72 submunitions. The rocket weighs 800 kg (the warhead accounting for 243 kg of this) and measures 7,600 mm in length (the warhead section being 2,049 mm long). The 220 mm 9M27K1 cargo rocket for the 9K57 Uragan (Ураган; ‘Hurricane’) MLRS is also capable of carrying the 9N235 submunition. When the cargo rocket carries 9N210 fragmentation submunitions (physically nearly identical to the 9N235), it has a range of between 10 to 35 km and can deliver 30 submunitions. The rocket weighs 270 kg (90 kg of which is the warhead) and measures 5,178 mm in length. The 9M55K and 9M27K cargo rockets are depicted in Figure 2.

The 9N235 submunition is, outwardly, nearly physically identical to the 9N210. The two can be positively differentiated by examining the markings on the submunition’s body (see Figure 1), however. Internally, the 9N210 differs from the 9N235 in that it contains only a single size of pre-formed fragments. The 9N210 submunition contains between 370 and 400 fragments formed from chopped steel rod, each weighing a nominal 2.0 g each. In addition, both the 9N235 and 9N210 feature a self-destruct mechanism, but the delay time is different—60 seconds for the 9N210 and 110 seconds for the 9N235. Note that several observers and commentators have erroneously claimed that the 9N210 is exclusively used with the 9M27K (Uragan) rocket, whereas the 9N235 can only be deployed from the 9M55K (Smerch) rocket. ARES has previously documented both submunitions deployed from both types of cargo rockets in Ukraine, Syria, and elsewhere.

Technical Characteristics

9M55K cargo rocket (with 9N235 submunitions)

Range: 20–70 km

Weight: 800 kg

Length: 7,600 mm

Warhead weight: 243 kg

Warhead length: 2,049 mm

Payload: 72 × 9N235 submunitions

9M27K cargo rocket (with 9N210 submunitions)

Range: 10–35 km

Weight: 270 kg

Length: 5,178 mm

Warhead weight: 90 kg

Payload: 30 × 9N210 submunitions

9N235 submunition

Length: 263 mm

Diameter: 65 mm

Weight: 1.75 kg

Explosive weight: 312 g

Explosive composition: A-IX-10

Number of preformed fragments per submunition: 96 × 4.5 g; 360 × 0.75 g

Fuze: 9E272 (impact)

Sources

ARES (Armament Research Services). n.d. Conflict Materiel (CONMAT) Database. Confidential. Perth: ARES.

Jenzen-Jones, N.R. 2014a. ‘9M55K cargo rockets and 9N235 submunitions in Ukraine’. The Hoplite. 3 July. <https://armamentresearch.com/9m55k-cargo-rockets-and-9n235-submunitions-in-ukraine/>.

Jenzen-Jones, N.R. 2014b. ‘9M27K series cargo rockets used in Ukraine’. The Hoplite. 11 July. <https://armamentresearch.com/9m27k-series-cargo-rockets-used-in-ukraine/>.

Jenzen-Jones, N.R. & Yuri Lyamin. 2014a. ‘9M55K Cargo Rockets and 9N235 Submunitions in Syria’. The Hoplite. 16 February. <https://armamentresearch.com/9m55k-cargo-rockets-and-9n235-submunitions-in-syria/>.

Smalwood, Michael & Yuri Lyamin. 2014. ‘9M27K Series Cargo Rockets in Syria.’ The Hoplite. 22 February. <https://armamentresearch.com/9m27k-series-cargo-rockets-in-syria/>

Human Rights Watch, 2022. ‘Ukraine: Cluster Munitions Launched Into Kharkiv Neighborhoods’. 4 March. Available via: <https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/Ukraine_%20Cluster%20Munitions%20Launched%20Into%20Kharkiv%20Neighborhoods.pdf>.

Remember, all arms and munitions are dangerous. Treat all firearms as if they are loaded, and all munitions as if they are live, until you have personally confirmed otherwise. If you do not have specialist knowledge, never assume that arms or munitions are safe to handle until they have been inspected by a subject matter specialist. You should not approach, handle, move, operate, or modify arms and munitions unless explicitly trained to do so. If you encounter any unexploded ordnance (UXO) or explosive remnants of war (ERW), always remember the ‘ARMS’ acronym:

AVOID the area

RECORD all relevant information

MARK the area from a safe distance to warn others

SEEK assistance from the relevant authorities

SEE LA REVUE GAUCHE - Left Comment: Search results for PERMANENT ARMS ECONOMY

WASHINGTON — General Atomics Electromagnetic Systems [GA-EMS] has announced that its contract with the Pentagon to design, prototype, and test projectiles in railgun and powder gun environments has ended after the company announced successful tests.

- GD to make 76 20mm six-barrel Gatling guns for the Navy’s F-18s

- THAAD successfully fired Patriot’s PAC-3 MSE missile using AN/TPY-2

- U.S. tested interaction sensors between a fighter jet and MUM-T

Simultaneously at two landfills in the United States – White Sands, New Mexico, and Dugway, Utah GA-EMS fired projectiles from the Navy’s 32-megajoule railgun and a 120mm powder gun. The development and testing of these weapon systems are part of the most modern US projects for the development and future commissioning of protective interceptor projectiles.

The shells fired by the two cannons reached hypersonic speeds, GA-EMS said in a press release. After being launched, projectiles’ guided flight capabilities were tested at both ranges. This test was important for GA-EMS because it was this company that supplied projectiles with integrated gun-hardened guidance electronics.

“Close communication among team members was critical to the outcome of this effort,” said Scott Forney, president of GA-EMS. “We tested significant advancements in our projectile design, demonstrating survivability and good aerodynamic performance at these velocities while testing guidance capabilities that promise greater precision and accuracy to effectively meet and defeat airborne threats.”

The company said it worked closely with the US Army Combat Capabilities Development Command Armaments Center [DEVCOM-AC] and the Naval Surface Warfare Center – Dahlgren Division [NSWC-DD] during the projectile development and testing process.

BulgariaMilitary.com reminds you that the idea of using railguns is becoming more and more applicable in the plans and military budgets of other countries as well. Japan, for example, has come up with the idea of using railguns to launch magnetic projectiles to intercept hypersonic missiles.

What railgun is?

Railgun is a pulsed electrode mass accelerator that converts electrical energy into kinetic energy using the Lorentz force. It emerged as a modification of the Gaussian cannon, capable of launching shells of any material and without the need for complex control and safety devices. Railgun is a promising weapon.

The railgun consists of two parallel electrodes, called rails, connected to a source of high-power direct current. An electrically conductive projectile or projectile carrier [armature] is located between the rails, closing the electrical circuit. “Armature” acquires acceleration under the action of the Lorentz force, which occurs when the circuit is closed in an excited increasing current magnetic field. A “reinforcement” can also be a clot of conductive plasma, which turns into a foil placed between the rails. When the “armature” is pushed by Lorentz force at the ends of the rails, the electrical circuit opens.

Railguns in orbit have the potential to be an effective weapon for destroying enemy missiles or protecting against asteroids. Also, railguns can launch cargo into orbit directly from the planet’s surface. In addition, they are suitable for initiating fusion or melting reactions of metals by colliding their samples at high speed.

9 MEPs want EU entry talks and funds halted if Serbia continues to refuse aligning with bloc’s position on Russia

Brussels/Belgrade, 13 March 2022, dtt-net.com – Nine members of the European Union (EU), of the Renew Europe group asked the European Commission (EC) to call Serbia once again to align fully with bloc’s position toward Russia over its military aggression on Ukraine, and sanction Belgrade if it refuses to do so.

EU expects from Serbia to “progressively” align with sanctions on Russia

Brussels/Belgrade, 14 March 2022, dtt-net.com – Candidate countries from the Western Balkans, and in this case Serbia, are “expected” to progressively align with EU positions on foreign and security policy related to the Russian military aggression against Ukraine, the European Commission (EC) officials reiterated today, as European lawmakers are stepping up calls to sanction Serbia over its refusal to join bloc sanctions on Russia.

Ukraine's largest steel firm says shells hit Avdiivka coke plant

·

LVIV, Ukraine (Reuters) - Ukraine's largest steel company Metinvest said shells hit the territory of its Avdiivka coke plant on Sunday, damaging some of its facilities.

Earlier, the general prosecutor's office said five rockets had hit the plant, which had already suspended operations in the wake of Russia's invasion of Ukraine.

Metinvest, majority-owned by Ukraine's richest man and business magnate Rinat Akhmetov, said nobody was hurt in the shelling, which hit two coking shops and other areas.

The site's thermal power plant, which supplies heat to the neighbouring town of Avdiivka, has stopped working, it said.

Avdiivka is one of the largest coke plants in Europe and the major manufacturer of coke for steel-making in Ukraine.

(Reporting by Max Hunder and Natalia Zinets; Writing by Alessandra Prentice; Editing by Hugh Lawson)

ICRC warns Ukraine’s Mariupol faces ‘worst-case scenario’

Mariupol city council says more than 2,000 people have been killed since the city was besieged by Russian forces.

Published On 13 Mar 202213 Mar 2022

More than 2,000 people have died in the city of Mariupol since Russia launched its war in Ukraine, the city council has said, as the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) warned that residents of the besieged port city face a “a worst-case scenario” unless the warring parties reach an agreement to ensure their immediate safety and access to humanitarian aid.

“To date, 2,187 Mariupol residents have died from attacks by Russia,” the Mariupol local council said on its official Telegram account on Sunday. Since the war in Ukraine began on February 24, it added, Russian forces have dropped about 100 bombs on the city, including 22 in the previous 24 hours.

Ukrainian authorities say the city has been subject to relentless bombardment since Russian troops surrounded it on March 2. Since then, the roughly 400,000 people who remain in Mariupol have been left with no access to water, food and medicine. Heat, phone services – and electricity in many areas – have been cut.

“The situation is catastrophic; it has been catastrophic for days,” the ICRC’s Jason Straziuso told Al Jazeera. “Even our team is collecting water from streams … but how does everyone do that … especially if you are elderly?” he asked. Straziuso said that his team members were eating one meal per day.

In a statement later on Sunday, the ICRC warned that time was “running out” for those trapped in the city.

“History will look back at what is now happening in Mariupol with horror if no agreement is reached by the sides as quickly as possible.”

ICRC president Peter Maurer called on all parties involved in the fighting to “place humanitarian imperatives first”.

The ICRC said “a concrete, precise, actionable agreement” was needed without delay so civilians wanting to leave can reach safety, and life-saving aid can reach those who stay.

Moscow has repeatedly justified its offensive in Ukraine, saying that it was conducting a “special military operation” attacking military targets. Last week though, Kyiv accused Russia of bombing a children’s hospital and a maternity ward and killing three people, while Mariupol’s local authorities on Thursday reported that city’s residential areas had been shelled “every 30 minutes”.

Mariupol city council says more than 2,000 people have been killed since the city was besieged by Russian forces.

A man walks with a bicycle in front of a building damaged by shelling in Mariupol, Ukraine

[Evgeniy Maloletka/AP]

Published On 13 Mar 202213 Mar 2022

More than 2,000 people have died in the city of Mariupol since Russia launched its war in Ukraine, the city council has said, as the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) warned that residents of the besieged port city face a “a worst-case scenario” unless the warring parties reach an agreement to ensure their immediate safety and access to humanitarian aid.

“To date, 2,187 Mariupol residents have died from attacks by Russia,” the Mariupol local council said on its official Telegram account on Sunday. Since the war in Ukraine began on February 24, it added, Russian forces have dropped about 100 bombs on the city, including 22 in the previous 24 hours.

Ukrainian authorities say the city has been subject to relentless bombardment since Russian troops surrounded it on March 2. Since then, the roughly 400,000 people who remain in Mariupol have been left with no access to water, food and medicine. Heat, phone services – and electricity in many areas – have been cut.

“The situation is catastrophic; it has been catastrophic for days,” the ICRC’s Jason Straziuso told Al Jazeera. “Even our team is collecting water from streams … but how does everyone do that … especially if you are elderly?” he asked. Straziuso said that his team members were eating one meal per day.

In a statement later on Sunday, the ICRC warned that time was “running out” for those trapped in the city.

“History will look back at what is now happening in Mariupol with horror if no agreement is reached by the sides as quickly as possible.”

ICRC president Peter Maurer called on all parties involved in the fighting to “place humanitarian imperatives first”.

The ICRC said “a concrete, precise, actionable agreement” was needed without delay so civilians wanting to leave can reach safety, and life-saving aid can reach those who stay.

Moscow has repeatedly justified its offensive in Ukraine, saying that it was conducting a “special military operation” attacking military targets. Last week though, Kyiv accused Russia of bombing a children’s hospital and a maternity ward and killing three people, while Mariupol’s local authorities on Thursday reported that city’s residential areas had been shelled “every 30 minutes”.

A view shows cars and a building of a hospital destroyed by an

aviation strike amid Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, in Mariupol, Ukraine

[Press service of the National Police of Ukraine/Handout Reuters]

The capture of the port city is strategically important to Moscow as it would link Russian-backed territories in the east with Russian-annexed Crimea in the south.

Several attempts to establish evacuation corridors to allow civilians to escape the city, and to allow humanitarian aid to enter, have fallen apart as previously agreed ceasefires collapsed.

Ukrainian authorities have accused Russia of deliberately opening fire on aid convoys heading towards Mariupol. Russia has blamed Kyiv for sabotaging ceasefire agreements.

On Sunday, another attempt was under way as Ukraine’s President Volodymyr Zelenskyy said that a convoy with humanitarian aid was two hours away from Mariupol.

“We’re doing everything to counter occupiers who are even blocking Orthodox priests accompanying this aid, food, water and medicine. There are 100 tonnes of the most necessary things that Ukraine sent to its citizens,” Zelenskyy said in a video address.

The president also said that nearly 125,000 civilians from other cities have been evacuated through safe-passage corridors in one day.

Amid collapsed ceasefires and trade accusations, Mikhail Podolyak, a member of the Ukrainian negotiating team, said on Sunday that there has been some progress in the talks with his team’s Russian counterparts.

Russia is not “putting ultimatums, but carefully listens to our proposals,” he said on Twitter.

SOURCE: AL JAZEERA

The capture of the port city is strategically important to Moscow as it would link Russian-backed territories in the east with Russian-annexed Crimea in the south.

Several attempts to establish evacuation corridors to allow civilians to escape the city, and to allow humanitarian aid to enter, have fallen apart as previously agreed ceasefires collapsed.

Ukrainian authorities have accused Russia of deliberately opening fire on aid convoys heading towards Mariupol. Russia has blamed Kyiv for sabotaging ceasefire agreements.

On Sunday, another attempt was under way as Ukraine’s President Volodymyr Zelenskyy said that a convoy with humanitarian aid was two hours away from Mariupol.

“We’re doing everything to counter occupiers who are even blocking Orthodox priests accompanying this aid, food, water and medicine. There are 100 tonnes of the most necessary things that Ukraine sent to its citizens,” Zelenskyy said in a video address.

The president also said that nearly 125,000 civilians from other cities have been evacuated through safe-passage corridors in one day.

Amid collapsed ceasefires and trade accusations, Mikhail Podolyak, a member of the Ukrainian negotiating team, said on Sunday that there has been some progress in the talks with his team’s Russian counterparts.

Russia is not “putting ultimatums, but carefully listens to our proposals,” he said on Twitter.

SOURCE: AL JAZEERA

Seabed mineral exploration licences approved in the Cook Islands

Caleb Fotheringham, Journalist Cook Islands News

Five kilometres deep on the Cook Islands seafloor, potato-shaped rocks pave the bottom loaded with expensive minerals like cobalt, copper, manganese and nickel.

Odyssey’s research vessel used for mineral exploration work in Papua New Guinea, Solomon Islands, Tonga, Fiji, Vanuatu and New Zealand Photo: Adam Stemm

They're called polymetallic nodules and three weeks ago the Cook Islands Prime Minister, Mark Brown referred to them as "golden apples".

Brown made the comment during an official signing ceremony where three companies were awarded a seabed minerals exploration licence.

The licence allows the companies to see if mining is a viable option which includes reviewing the environmental risks associated with the task.

Brown, who is also the Minister for the Seabed Minerals Authority, compares the Cook Islands situation to Norway - a country that enjoys some of the highest standards of living in the world, made possible through abundant natural resources.

Brown sees the expensive minerals bringing infrastructure improvements to airports, ports and schools.

The Pa Enua (outer islands) will have drinking water security - something that's always been a challenge but has been made worse through climate change.

High-speed internet will be available throughout the entire nation and Cook Islanders living overseas could even be beneficiaries of education scholarships in whatever fields or universities they choose.

A more short-term benefit would be retaining some of the Cook Islands population who are leaving for New Zealand's far more attractive wages.

(L-R) George George Williamson, Bishop Tutai Pere, Maru Mariri, Hon.Mark Brown, Makiroa Mitchell, Makiuti Tongia and Sam Napa. Photo: Cook Islands Seabed Minerals Authority

"Today our people are leaving to pick apples in New Zealand, tomorrow, we will have our own apples to pick, and they sit on the floor of our ocean," Brown said at the ceremony which was followed by a round of applause.

Three companies given the licence are Cook Islands Colbalt (CIC) Limited, Moana Minerals Limited and Cook Islands Investment Company (CIIC) Seabed Resources Limited which is co-owned by the Cook Islands Government.

These companies are based around the world and share joint ownership with other mining companies. All companies have budgeted between $55.4 million to $71.7 million to conduct the exploration process over the next five years.

Despite the riches the "golden apples" are promising, many nations and environmental groups like Te Ipukarea Society, a non-government organisation in the Cook Islands, has called for a 10-year-moratorium on seabed mining, something the Cook Islands Government with support from the opposition party have vocally opposed.

Even companies like BMW, Renault and Microsoft - companies who would be beneficiaries of the mining have supported a moratorium.

Tech giant, Microsoft said in a report that due to the early nature of deep-sea mining the company will wait "until the proper research and scientific studies have been completed" until using any of the minerals.

Goldman Environmental Prize winner and marine conservationist, Jacqueline Evans says seabed mining has a direct impact on the biodiversity that lives on and around the nodules. The disposal of sediment from the ship will also impact marine life, she says.

Polymetallic nodules Pacific ocean Photo: Velizar Gordeev. All rights reserved.

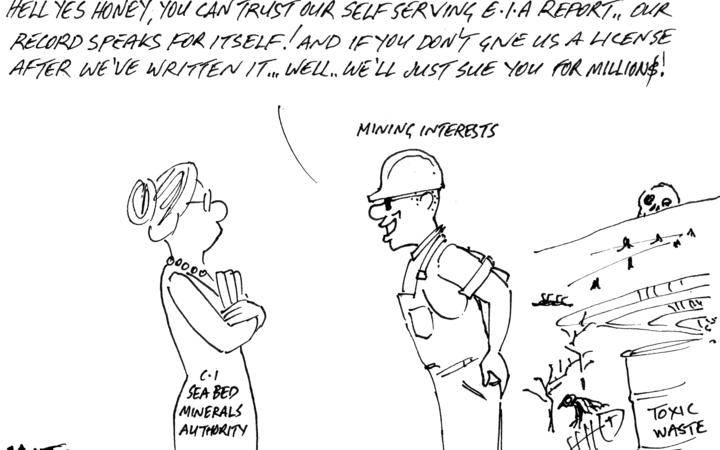

Another concern of Evans and the technical director at Te Ipukarea Society, Kelvin Passfield, is the companies could be reluctant to leave if they're granted a mining licence.

Passfield says, "our concern is they're not expecting to spend that money and say, 'oh it looks like the environmental impacts are not going to be good, so we're going to pack our bags and leave'."

"We need to be sure that does happen and if the impacts are going to be too great that they will pack their bags and leave, and the Cook Islands is not going to be put under any pressure to award them a licence.

"These companies, they're in the business of making money, they're in the business of pouring millions of dollars of investors' money into the seafloor.

"Their expectation is they're going to get an exploitation (mining) licence."

The Cook Islands have rules in place in the exploration legislation that protect the companies.

Photo: Cook Islands New

Evans says, "the legislation doesn't allow us to deny a mining licence for whatever reason - there are pre-stated reasons for denying a licence. This favours the mining companies more than it favours ourselves."

The concerns of being sued are exacerbated by ongoing litigation between Odyssey Marine Exploration, which is a joint owner of CIC - one of the Cook Islands companies with an exploration licence - and the Mexican Government.

Odyssey is seeking more than $US2.3 billion from Mexico after being denied a mining licence by the Mexican government.

Dr Catherine Coumans, the Asia-Pacific programme coordinator for Canadian non-profit organisation MiningWatch Canada, has experience supporting governments fighting costly, years-long legal battles against mining corporations.

Coumans says the Mexican government denied the licence on the grounds that the proposed mining would endanger turtles, whales and fishing grounds. It was also based on a lack of public consultation.

Mining for copper under the sea Photo: Nautilus Minerals

However, the president and chief operating officer of Odyssey, John Longley says his company was already granted a 50-year mining license for extracting phosphate sands in Mexico and the company found there would be "minimal environmental impact backed by extensive research".

"The government did not apply fair and equitable treatment to the evaluation of the project and environmental application, illegally denying the license," Longley says.

Odyssey claims Mexico is depriving citizens in the United States of certain rights, going against the North American Free Trade Agreement between the US, Mexico and Canada.

Before the exploration licences were awarded the licencing process was open to public feedback. Cook Islands Seabed Minerals is the Cook Islands regulator for seabed minerals, Alex Herman the commissioner, says a key issue brought up in the submissions was around environmental data collection.

The environmental impact assessment of the potential harms of mining the minerals rests with the applicant, she says. Which means companies will pay for their own assessment.

However, she says the independent review is normally part of the process and will also be commissioned by the companies.

The main environmental case for deep-sea mining is that rare metals are needed if the world is to ever transition away from fossil fuels.

Adam Stemm (left), chief operating officer of CIC, Greg Stemm, chairman and founder of CIC and Laurie Stemm, founder of Cook Islands Traditional Arts Trust. Photo: Adam Stemm

Greg Stemm, chief executive officer of CIC says "currently there is insufficient metal in the system to meet the exponentially increasing demand for metals to enable the energy transition, until we reach a critical mass, which may not be for 25-50 years from now, then new raw materials must be sourced."

Stemm says if the rare earth metals could be extracted in the Cook Islands it could "save rainforests and other environmentally sensitive areas on land".

"If there is any possibility that it can be done with significantly less environmental impact than on land, it seems ridiculous to suggest that we should not at least be conducting research to determine the viability of ocean minerals."

US Blockade Against Cuba to Be Rejected by Media Marathon

Image of young people in Havana, Cuba.

“This action is intended to remind us that Cuba is not alone in its fight against the infamous blockade,” Al Mayadeen outlet said, adding that it will join the marathon to “raise its voice against a unilateral policy repudiated almost unanimously by the international community and rejected by the United Nations General Assembly through 29 resolutions.”

Wafica Ibrahim, the Al Mayadeen Latin America Director, said that her outlet would present videos, cartoons, and interviews during the 24-hour marathon.

"In our editorial policy, Cuba and its example of struggle and resistance against the empire have a prominent role," she said.

“We want more and more people to join the call... We want the peoples to raise their voices so that their governments listen to them and condemn this policy and other atrocities that are committed there and in other parts of our planet, such as what is happening in Palestine, a nation blockaded and humiliated by Israel. And the world does nothing."

Over 100 Cuban radio stations and international media such as Prensa Latina, Resumen Latinoamericano, HispanTV, and Sputnik will take part in the marathon. They will be joined through social networks by organizations in solidarity with Cuba from around the world.

Political organizations such as the Rebellious France Party (LFI), the Communist Party of Spain (PCE) and the Communist Party of the Peoples of Spain (PCPE) will also support this communication initiative.

Image of young people in Havana, Cuba.

| Photo: Twitter/ @EmbacubaNZ

Published 14 March 2022

"We want the peoples to raise their voices so that their governments listen to them and condemn this policy," the Al Mayadeen Latin America Director said.

On April 2, the "Europe for Cuba" channel will lead a "World Media Marathon" to reject the U.S. blockade against the Cuban Revolution.

Published 14 March 2022

"We want the peoples to raise their voices so that their governments listen to them and condemn this policy," the Al Mayadeen Latin America Director said.

On April 2, the "Europe for Cuba" channel will lead a "World Media Marathon" to reject the U.S. blockade against the Cuban Revolution.

RELATED:

“This action is intended to remind us that Cuba is not alone in its fight against the infamous blockade,” Al Mayadeen outlet said, adding that it will join the marathon to “raise its voice against a unilateral policy repudiated almost unanimously by the international community and rejected by the United Nations General Assembly through 29 resolutions.”

Wafica Ibrahim, the Al Mayadeen Latin America Director, said that her outlet would present videos, cartoons, and interviews during the 24-hour marathon.

"In our editorial policy, Cuba and its example of struggle and resistance against the empire have a prominent role," she said.

“We want more and more people to join the call... We want the peoples to raise their voices so that their governments listen to them and condemn this policy and other atrocities that are committed there and in other parts of our planet, such as what is happening in Palestine, a nation blockaded and humiliated by Israel. And the world does nothing."

Over 100 Cuban radio stations and international media such as Prensa Latina, Resumen Latinoamericano, HispanTV, and Sputnik will take part in the marathon. They will be joined through social networks by organizations in solidarity with Cuba from around the world.

Political organizations such as the Rebellious France Party (LFI), the Communist Party of Spain (PCE) and the Communist Party of the Peoples of Spain (PCPE) will also support this communication initiative.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)