March 13, 2022

LINDA HOLMESTwitter

NPR

Billy Joel plays in Moscow in 1987.ABC Photo Archives/Disney General Entertainment Content/Getty Images

As a Gen-X kid, I have to admit there was particular poignancy to the news that, following the Russian invasion of Ukraine, Russia isn't getting The Batman.

It's part of a much, much bigger and more important story, of course — several much, much bigger, much more important stories. NPR's Anastasia Tsioulcas has reported on many severed relationships in arts in recent weeks.

All three major music labels have now suspended operations in Russia

Most of these have been attributed not simply to being Russian in and of itself, but to ties to Putin, or to a refusal to repudiate him — and to funding that comes from the Russian government. Some artists have actively spoken against him and against the invasion, but many have not. It's in opera, it's in classical concerts, but it's affecting other things, too: Russia is not being permitted to participate in Eurovision, where it debuted in 1994. Western musicians have been canceling Russian dates ever since the war started. As Elizabeth Blair has reported, Russian cultural organizations inside the U.S. are anxious about possible effects on their own work.

Bon Jovi, Motley Crue, and Ozzy Osbourne played at the Moscow Music Peace Festival in August, 1989.Robert Toning/AP

Billy Joel plays in Moscow in 1987.ABC Photo Archives/Disney General Entertainment Content/Getty Images

As a Gen-X kid, I have to admit there was particular poignancy to the news that, following the Russian invasion of Ukraine, Russia isn't getting The Batman.

It's part of a much, much bigger and more important story, of course — several much, much bigger, much more important stories. NPR's Anastasia Tsioulcas has reported on many severed relationships in arts in recent weeks.

All three major music labels have now suspended operations in Russia

Most of these have been attributed not simply to being Russian in and of itself, but to ties to Putin, or to a refusal to repudiate him — and to funding that comes from the Russian government. Some artists have actively spoken against him and against the invasion, but many have not. It's in opera, it's in classical concerts, but it's affecting other things, too: Russia is not being permitted to participate in Eurovision, where it debuted in 1994. Western musicians have been canceling Russian dates ever since the war started. As Elizabeth Blair has reported, Russian cultural organizations inside the U.S. are anxious about possible effects on their own work.

Bon Jovi, Motley Crue, and Ozzy Osbourne played at the Moscow Music Peace Festival in August, 1989.Robert Toning/AP

Connections to Russia were once optimistic

These boycotts are perhaps even more jarring if you remember past periods in which pop culture tried to paint a picture of deliberate, optimistic, post-Cold-War thaw. In the 1980s, particularly in the wake of the policies of glasnost and perestroika in the former Soviet Union — which encouraged openness and reform — artists went to places they wouldn't have gone ten or even five years before. It was in 1987, 35 years ago this July, that Billy Joel brought a big pop-rock show to Leningrad and Moscow; 1989 when Billy Crystal traveled to find his Russian relatives in an HBO special called Midnight Train to Moscow. That year also brought the Moscow Music Peace Festival, with Ozzy Osbourne, Motley Crue, and Bon Jovi among the performers.

At the time, all these things were presented through a lens of, for lack of a better word, a goal of international — and intentional — friendship. Joel's bond with an enthusiastic fan and circus clown named Viktor became one of the centerpieces of the documentary about his trip and the basis for a later song called "Leningrad." ("We never knew what friends we had until we came to Leningrad.")

Ukraine's libraries are offering bomb shelters, camouflage classes and, yes, books

After Putin became president in 2000, some of these events continued. Paul McCartney played in Red Square in 2003 and met with Putin personally. Putin came to the show. Even the popularity of the FX drama series The Americans, which portrayed the Cold War through the eyes of KGB spies who felt just as righteous in their cause as Americans did in theirs, arguably continued this tradition of pop culture as pushing back against simplistic and antagonistic narratives of decades past.

And now all this.

Russian President Vladimir Putin meets with Paul McCartney during their meeting at the Kremlin on May 24, 2003 in Moscow. Getty Images

Even Levi's has halted sales in Russia

This severance of sometimes longstanding relationships isn't only happening in the arts. It's happening just as rapidly in sports, both in the real world and virtually. Russian athletes were barred from the Paralympic Games by the International Olympic Committee. FIFA has banned Russian teams from participating in its soccer matches. Russian teams have even been removed from the popular FIFA 22 video game, and may be removed from other games, too. President Vladimir Putin is seeing symbolic ties to sports withdrawn: The International Judo Federation stripped Putin of honorary titles in that sport, and World Taekwondo withdrew an honorary black belt.

Businesses that one might paint into a mural representing American consumerism have been suspending business in Russia: McDonald's, Coke, Pepsi, Starbucks, Disney. Wall Street saw its first big withdrawal when Goldman Sachs stopped operating there, and while that's an economic move, it feels culturally significant, too. Hollywood studios, major music companies, all ceasing business in Russia — there are even ramifications for sales of one of the items that has often been referenced as a go-to symbol of American cultural presence in other countries: blue jeans.

The impact of cultural boycotts

Does all this matter? It probably depends on what you mean by "matter." As Yasmeen Serhan wrote in The Atlantic earlier this month:

"It's easy to see cultural boycotts as more of a symbolic act than a serious threat to Moscow's geopolitical standing. But by suspending Russia from the world's largest sporting and cultural arenas, these institutions are sending a clear—and, for Putin, potentially damaging—message: If Russia acts beyond the bounds of the rules-based international order in Ukraine, it will be treated as an outsider by the rest of the world."

The idea of culture and sports as stand-ins for the current political climate is obviously not new. I was an enthusiastic Olympics-watching kid during the boycott by the United States of the Moscow Summer Olympics in 1980 and the Soviet Union's boycott of the Los Angeles Summer Olympics in 1984, both of which cost athletes dearly, and both of which carried a heaviness, a sense of a hostile closed door that was consistent with the political rhetoric of the time. And in the last couple of years, the controversies around Russian athletes in the Olympics and the workaround under which sanctions for doping meant they couldn't compete for Russia but only for the "Russian Olympic Committee" brought out some of the grumbling that has soured international competition in the past.

Pianist Van Cliburn performing in the final round of Tchaikovsky International Competition in Moscow in 1958. Cliburn's triumph helped thaw the Cold War.

AP

Why Brittney Griner was in Russia and what it has to do with U.S. women's basketball

And it goes back much farther than that: In the documentary about his trip to Russia, Billy Joel says he was inspired to go partly because he remembered how important it felt to him when he was young and American pianist Van Cliburn won the International Tchaikovsky Competition in Moscow in 1958. Joel says in the film that the event, and Russia's embrace of Cliburn, changed his own sense of the country and its people, whom he felt he'd been taught to fear.

The world has always done this — used culture and sports to communicate over and past and through and around politics and aggression — and the question of how important that is, and how productive it is, recurs.

These crossovers of diplomacy and art can be fortuitous or commercial, but they can also be fully orchestrated by governments, and they can be complicated for the artists involved: the U.S. State Department sent jazz musicians, including Dizzy Gillespie and Louis Armstrong, around the world in the 1950s to present a positive image of the United States, even as the country utterly failed to treat them equally.

The world has always done this — used culture and sports to communicate over and past and through and around politics and aggression — and the question of how important that is, and how productive it is, recurs.

The efficacy of cultural sanctions certainly remains an open question; Serhan argues that because of the particular shape of his chosen image, Putin will be far more personally bothered and functionally threatened by sports sanctions than by ones in the arts. But she says this, too: "If ordinary Russians can no longer enjoy many of the activities they love, including things as quotidian as watching their soccer teams play in international matches, seeing the latest films, and enjoying live concerts, their tolerance for their government's isolationist policies will diminish."

By now, Russians have gotten used to global connections

If that's so, it may turn out that openness — not just concerts in the 1980s, but the growing presence of Hollywood films and the vibrancy of international competition in sports — is not just a cyclical opposite of this period of retraction we've so rapidly entered, but a logical predecessor to it. The idea of depriving ordinary Russians, as Serhan says, of sports and Hollywood films and live concerts by international performers would not be a potent threat had they not come to expect access to those things in the first place.

If that's so, it may turn out that openness — not just concerts in the 1980s, but the growing presence of Hollywood films and the vibrancy of international competition in sports — is not just a cyclical opposite of this period of retraction we've so rapidly entered, but a logical predecessor to it. The idea of depriving ordinary Russians, as Serhan says, of sports and Hollywood films and live concerts by international performers would not be a potent threat had they not come to expect access to those things in the first place.

Ukrainian heritage is in peril. The Smithsonian hopes to rescue what it can

In other words, if bands weren't going to Russia, if world sports leagues weren't thriving, if Hollywood movies weren't earning big money from big audiences in Russia, these arts and sports sanctions would be empty. If you're not part of Eurovision, you can't be excluded from Eurovision. If people don't have expectations of a relatively open cultural and sports world, they can't be disappointed.

As a wildly naive teenager, I did find the idea that anyone could rock out at a concert transformative, capable of papering over what remained deep and troubling problems in world affairs that existed in both my own country and others.

But this is not the way this openness was pitched in the pop culture of the 1980s and 1990s, as something that might be withdrawn later as a result of an invasion; it was pitched as hope, as comity, and as perhaps a permanent realignment. And as a wildly naive teenager, I did find the idea that anyone could rock out at a concert transformative, capable of papering over what remained deep and troubling problems in world affairs that existed in both my own country and others. Even in 1987, Joel was asked whether he was afraid that his visit would be used as cover for human rights issues. His response, so familiar to people who have watched artists navigate these issues, was that he was not a politician.

There will likely be — there will hopefully be — at some time in the future, brought about by different conditions and an end to the war, another newsworthy return to Moscow for an American pop artist. There will be another reopening, another thaw in this cycle. The Gen-X kid in me, the one who remembers being sold hope in that way, anticipates this and will lean toward music and sports for signs of peace, even knowing it's foolish. It isn't that arts or sports are the important ties; it is that they are buoys that bob on the surface of world affairs, and when they move, in response to much greater forces underneath them, we notice.

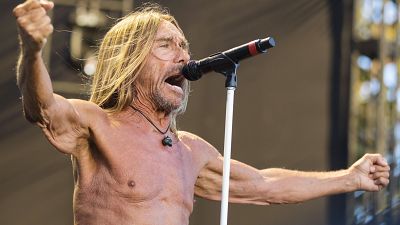

'Our thoughts are with the Ukrainians' says Iggy Pop as acts pull out of Moscow rock festival

Iggy Pop, Placebo, and Biffy Clyro are among those pulling out of Russian festival Park Live - Copyright Colin Young-Wolff/AP

By Paul Stafford • Updated: 11/03/2022 -

One after another, internationally renowned musicians are cancelling all upcoming concerts and festival appearances on Russian soil.

Iggy Pop was among the first to withdraw from the Park Live festival in Moscow last week, which is scheduled to take place over three weekends in June and July 2022.

“In light of current events, this is necessary. Our thoughts are with the Ukrainians and all the brave people who oppose this violence and seek peace,” the enigmatic punk rocker noted in a statement posted on Twitter.

Other bands followed suit. Biffy Clyro, The Killers and Placebo all dropped the Park Live festival from their tours, while Green Day, Bjork and Iron Maiden cancelled appearances at various events across Russia in the coming months.

The Revolution Will Be Televised

During the Cold War, Western music was one of the more potent links between the isolated citizens of the Soviet Union and the outside world, seeping through the Iron Curtain in the form of bootlegged, black-market cassette tapes and records.

By 1989, the Glasnost “openness” policy under then General Secretary of the Soviet Union, Mikhail Gorbachev, led to musicians performing live in Moscow to hundreds of thousands of people. But just as these performances reflected an influx of new freedoms for Russian people, so the current cancellations in Russia reflect their erosion.

Most of the bands signed up to Park Live in Moscow this year were also scheduled to play a sister festival in Kyiv called UPARK Festival. Thanks to Russia’s invasion of its neighbour it is now highly unlikely that either event will take place.

Fashion and Protest: How Blue and Yellow might become the new black

Ink and Blood: How has Ukrainian Literature changed since 2014?

“As it stands the Ukrainian one is in an active war zone and the Russian one all countries are advising against travel to, making it impossible to do for international acts,” said Geoff Meall, an agent at Paradigm Talent Agency who represents the bands Sum 41 and My Chemical Romance. Both bands were due to play at Park Live and UPARK this summer.

“Not that there is anything tangible to actually pull from, as the event, of course, won't happen,” he said. Park Live, which was first held in 2013, has not run since 2019, with the 2020 and 2021 iterations both cancelled due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Under Pressure

With Park Live still not officially cancelled, ticket holders, many of whom held onto their tickets initially bought for 2020’s cancelled event, are taking to the festival’s Instagram page to voice their frustrations.

“Longest term investment of my life,” said one user, @juliet.estrina. Many other users complained of not being able to get refunds on their tickets, or criticised the indefinite postponement.

“As you can imagine the organisers of the events there are heartbroken at the turn of events. The Ukrainian team have had to escape Kyiv,” said Meall, about the current situation.

No official comment has been made about the proposed plans for Park Live and there have been no updates about the cancellations since March 3. Meanwhile, comment posting on Park Live’s VK page – a Russian social media platform still largely accessible in Russia – was closed.

Melnitsa International, the organisers of Park Live in Moscow, did not respond to requests for comment, although daily updates on their social media pages only add to the number of cancelled tours and gigs, spelling the end of Western musicians playing live concerts in Russia for the foreseeable future.

Festivals for Peace, not War

The international music community’s growing embargo on playing live in Russia stands in stark contrast to the Moscow Peace Festival, which took place in Luzhniki Stadium (then named the Central Lenin Stadium) on August 12th and 13th of 1989.

'Every coffee break you take costs a life': Ukrainian author criticises world leaders

Former Miss Ukraine describes terrifying escape from Kyiv and asks US to relax visas for refugees

Metal bands from Europe and the US, including The Scorpions, Ozzy Osbourne and Mötley Crüe, played two shows at the festival in the Russian capital to promote peace and the abstention of drug use.

Ironically, many of the musicians who have spoken about the festival in the years since, such as Scorpions frontman Klaus Meine, are quick to mention that many of the party travelling to Moscow were drinking and using drugs the moment the plane took off.

A little over two years later, the Soviet Union was dissolved and much of Eastern Europe was gradually reintegrated into the international community. And in Russia, music remains a vehicle for political opinion. Punk rockers Pussy Riot are among Russian President Vladimir Putin’s most vocal and visible opponents.

'We will have another cultural revolution': Ukrainian artists respond to Russian invasion

Nadezhda Tolokonnikova was among three of the band members convicted of “hooliganism motivated by religious hatred” and sentenced to prison time following a performance at Moscow's Cathedral of Christ the Saviour in 2012.

On cancelling their appearance at Park Live, Placebo’s official statement read: “We stand firmly against the atrocious war currently waged against Ukraine”.

At the time of writing, Park Live is still scheduled to take place with a number of top-end rock acts remaining on the bill.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/70615483/how_putin_falls_secondary_1bv2.0.jpg)

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/23306704/how_putin_falls_secondary_2b.jpg)

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/23307375/GettyImages_1238728652.jpg)

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/23306690/how_putin_falls_board_2c.jpg)

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/23307160/GettyImages_470588579.jpg)

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/23307061/GettyImages_955002576.jpg)