US Labor Today and the Way Forward

The labor movement in the United States used to be respected and looked to for leadership; people cared about what positions labor took, watched when they mobilized, and noticed the causes they supported. This was especially true among the left. Today, for most of the country, crickets. Including much of the left. And yet, labor is a source of potential power unrivaled by any other bottom-up social grouping in the country.

As one who has written extensively about labor around the world and in the United States—see my list of publications with many linked to the original articles—I have been thinking over several years about the future direction of the US labor movement. But this thinking is not just based on writing or just academic research; I’ve done that and also have years of experience as a labor activist and as one who has worked in blue, white, and pink collar jobs over the past 40+ years and in multiple locations across the country.

I argue that we haven’t had a labor movement in the US since 1949, when the CIO (Congress of Industrial Organizations) expelled 11 so-called “left-led” unions with somewhere between 750,000 and a million members; we’ve had only a trade union movement. What’s the difference? A labor movement looks out for the well-being of all working people in the country, while a trade union movement only looks out for members of its member unions.

And, especially since 1981, when the trade union movement failed to defend the striking air traffic controllers in the PATCO (Professional Air Traffic Controllers Organization) strike when attacked by President Ronald Reagan, the trade union movement leaders have done little but watch its ranks shrink, its prestige fall, and its power decline. Millions of jobs have been shipped overseas while the manufacturing economy has been decimated, and most of the service sector jobs since created have remained ununionized, underpaid, and with many fewer protections for workers. Yes, acting together, the trade union movement has worked to elect Democrats such as Bill Clinton and Barack Obama to office, but between signing NAFTA (North American Free Trade Act) in 1994, and the failure to pass a bill to enhance labor organizing, I’d say neither could be considered blazing successes. Individual unions have succeeded here and there, but only episodically and not consistently, and usually only because of some tactical feature that gave it a winning advantage in a particular struggle. Inspiring not.

The only consistent trade union success since the early 1980s has been in sucking up US government money—often between $30-75 million annually—which has allowed AFL-CIO foreign policy leaders to act behind the backs of most of the organization’s leaders and all of its affiliated union members, in our name, in efforts generally intended to undercut foreign workers’ struggles against multinational corporations and US government foreign policy projects.

Worse, even while nonetheless being helpful to foreign workers in a few cases, the AFL-CIO has acted to legitimize the imperialist National Endowment for Democracy (NED) by serving as one of its four “core institutes,” along with the international wing of the Democratic Party, the international wing of the Republican Party, and the international wing of its domestic archenemy, the US Chamber of Commerce, in NED’s on-going project of supporting and advancing the US Empire.

Thus, the trade unions’ leadership has generally done little to advance the interests and well-being of US workers, while acting in differential manners—usually bad—with foreign workers. I don’t think this was what Karl Marx and Frederick Engles were expecting when they echoed the French feminist, Flora Tristan, urging “Workers of the World, Unite!”

Yet, despite the general failure of the trade union movement leadership, especially since 1981, the reality is that unions are one set of institutions that, at their best, are of the workers, by the workers, and for the workers. You see workers fighting to make their unions “real”—trying to make them part of a labor movement that serves the interests of all workers if not the entire society—over the years. We see workers creating reform movements over the years trying to transform their unions for the benefit of the entire membership if not all workers.

Perhaps the most famous of late has been the reform organization UAWD (Unite All Workers for Democracy) inside the United Auto Workers. UAWD came together to fight for direct elections of UAW leadership instead of the convention elections, which had led to a one-party state since 1946 and the election of Walter Reuther. Over time, a number of top-level UAW leaders were charged with corruption, and in a consent agreement with the Federal government, the UAW had to shift to direct elections for top officers. UAWD put forth a partial slate headed by Shawn Fain, and then proceeded to win every leadership position they sought, ultimately gaining control of the international union’s executive board. In turn, Fain and his administration led the 2023 fight against the Big Three auto companies—General Motors, Ford, and Stilantis, the parent of Chrysler—which then won their strike in the Fall. While the UAW did not win all of its demands in the strike, it clearly demonstrated the power of organized workers who have a leadership that will fight for and with them. And following that successful strike, Volkswagen workers at Chattanooga, Tennessee voted to join the UAW, with help from the German union, IG Metal, although in the face of governors from six southern states telling them to not do so.

It is important to understand that unions are important to many workers, that they make e a difference in the workplace, and they usually mean higher wages, better benefits, seniority systems, and a recognizable “rule of law” in the workplace, the latter which places some limits on management authority and discipline; a big difference from the situation of most workplaces where workers give up most if not all of their rights when they enter company grounds.

So, where does this lead us?

I want to build off a study that I did originally for my PhD dissertation in 2003. It was a comparative-historical sociological study of unionization in the steel and meatpacking industries in the greater Chicago area (including Northwest Indiana) between 1933 and 1955, examining how the unions addressed racial oppression in the workplace, union, and communities in which these workers operated. Long story short: despite drawing from the exact same labor pool—white ethnics from eastern and southern Europe, African Americans from the rural South, and some Mexicans—the steelworkers’ organizations ignored the issues of white supremacy and racism, while the packinghouse workers directly confronted it: in 1939, in racist, segregated Chicago, eight out of 14 packinghouse local unions were headed by African Americans!

From this study, and differing from much research on the CIO (Congress of Industrial Organizations), the labor organization both of these unions ultimately joined, I recognized there were two different conceptualizations of trade unions within the CIO; ultimately, I referred to that of the steelworkers as “business” unions and that of the packinghouse workers as “social justice” unions. This was important because I found that how the members thought about their union determined subsequent organizational behavior.

And that brings things to where we are now: there are still two forms of unionism available to unions and their members. Business unions focus the power they can mobilize to fight for workers in the workplace, such as wages, working conditions, seniority, “rule of law,” etc. However, they generally ignore anything beyond the workplace, despite workers having lives outside of the workplace. Social justice unions focus that power in the workplace to not only address workplace issues, but they use the power in the workplace to also address things in workers’ lives beyond the workplace, including things such as racism, misogyny, and homophobia, as well as things like health care, education, the climate crisis, etc. Ideally, unions becoming or transforming themselves into social justice unions would consider the range of interests from the local to the global, ultimately seeking to join with unions and other people’s organizations around the world to make things better for all.

Recognizing these two different possibilities and what union members want to do in light of this understanding is important. It is important that these issues get discussed by the members of each union themselves; this is not limited to union leadership or even activists.

The reality is that the trade union movement today is so weak that unions rarely have a chance to win their battles without gaining public support. Unions have often recognized this and have appealed to community support to help them win their battles. Yet, what do the communities get back from the unions? Often nothing. This one-way form of “solidarity” is simply not sustainable; you can only withdraw from the well so many times without giving back before it runs dry.

Transforming business unions into social justice unions offers a solution: they build on their foundation in the workplace but join with community members—however defined—to work together in ways to improve life for all concerned.

There are issues that simply cannot be solved on a local, regional, or even national basis; the climate crisis jumps immediately to mind, although there are other issues such as global sexual slavery and related issues, pandemics, war and empire that can only be approached from a global perspective. We have to understand issues such as these from a global perspective and begin educating and organizing our union sisters and brothers on this level. But our ideas about our unions must at least allow for this, if not actively encourage work on this level by all members. Key to this is implementing an educational program that confronts these issues and encourages workers to think about how their union could work to address issues key to workers in this larger sense. The old slogan, “Think globally, act locally,” encapsulates these ideas.

This, however, is not going to change by itself: activists in each union need to stimulate discussion within their organization about whether they should confine their unionism just to the workplace, or to use that power for the good of all.

I would suggest trying to find a group of union members that think having this debate within one’s union to be crucial, and work to unify this core. Then they could create a campaign to spread this issue throughout the union, initially through one’s workplace and/or local and then through the national or international union they are affiliated with. It should be run the same way as any organizing campaign, and that is to win.

When confronted by this question—how do we want our union to go forward, alone or with our neighbors (from the local area to the globe)?—this is a question that encourages workers to think about these issues and get involved in participating in strengthening the union. Once a union is seen as something everyone participates in, or at least as many as possible, instead of just something that “others” do, we strengthen our individual unions. When we come to common responses, then we can extend our conceptualization of the union to other unions, locally, regionally, and nationally.

This can be extended globally when we find out what is happening elsewhere: there are workers around the world seeking to join globally to fight for a better world for all. Yes, this is happening among workers in other imperial countries but, as we see in the case of SIGTUR (Southern Initiative on Globalization and Trade Union Rights), workers in Africa, Asia and Latin America are finding ways to unite across their geographical regions and the globe to organize for a better world for all. I think they would be delighted to have North Americans join in their project, and that can only happen when unions take that broader, social justice union approach.

In short: innovate or stagnate. The business unionism of the past 40 years (in particular) has been a failure. Either we think about unionism in new ways and establish new ways of thinking about and joining other movements, or most of our unions die a long, slow, painful death.

It’s time we start rebuilding the labor movement: for the good of all!

United Auto Workers members at the University of California marched in Oakland. Attacks on campus occupations have led to unfair labor practice charges and even a strike vote. Photo: UAW Local 2865.

A growing number of unions have taken a stand against Israel’s genocide in Gaza. Yet US labor law throws up major obstacles to unions using their leverage to press political demands, including the demand for a cease-fire.

As university encampments have become the center of American popular resistance to Israel’s genocide in Gaza, the most powerful voices in the country calling for a cease-fire continue to be labor unions. For many, the logical next step after endorsing a cease-fire would be for unions to take more concrete actions to press this demand. The problem for unions is figuring out how to maximize pressure on the corporate and political classes who enthusiastically (and profitably) support Israel’s apartheid regime and genocide in Gaza, given that US labor law intentionally restricts the ability of unions to use workplace actions for political ends — like striking to stop a war.

The difficulty is that US labor law generally only protects workplace actions when there is a nexus between what is being protested and the working conditions of the employees taking action. Generally, rights to free speech and political expression stop at the workplace door. In this respect, bosses have greater control over workers than the elected government does over citizens, because the Constitution restricts governments but not private actors. (Even government agencies have more power to restrict expression when they are acting as employers.) This means that, with few exceptions, bosses can easily squash their workers’ political expression and speech.

A History of Making Effective Methods Illegal or Unprotected

The difference between an illegal activity and an unprotected activity is important, but often it makes little difference for workers. If an activity is illegal, then there are legal repercussions for doing it, like criminal charges or liability for damages. These exist on top of any employment repercussions. If an activity is not protected by the National Labor Relations Act (NLRA), then it means that workers can be fired for doing it and have no legal recourse for getting their jobs back. This vulnerability stems from the absence of constitutional rights in the workplace.

US labor law has a long history of taking tactics that unions use successfully and making them illegal or unprotected. After the passage of the NLRA in 1935 gave workers and unions legal rights to organize, strike, and bargain collectively, unions stepped up political donations to worker-friendly candidates. In 1943, Congress lumped unions in with banks and corporations as entities forbidden to donate to federal candidates. The sit-down strikes that were so effective in the late 1930s were soon declared illegal by the Supreme Court. A similar fate befell intermittent strikes, which are not illegal, but were determined to be unprotected.

The Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938 (FLSA), which established a minimum wage and overtime pay for hours over forty, put so much money into workers’ pockets that it had to be reined in. In 1946, the Supreme Court held that “time during which an employee is necessarily required to be on the employer’s premises, on duty or at a prescribed workplace” counted as work for FLSA purposes. Within six months, unions and employees had filed 1,500 lawsuits seeking $6 billion ($93.67 billion in 2023 dollars) in unpaid wages.

Congress scurried in to defend capital by enacting the Portal-to-Portal Act in 1947, which excluded most “work-adjacent” time by only counting “principal activities” as work that requires compensation under the FLSA. It also prohibited unions from bringing FLSA lawsuits on behalf of their members. The pendulum has swung so far the other way on this issue that, in 2014, the Supreme Court unanimously held that an Amazon contractor could legally force its employees to stand in line for twenty-five minutes for a security screening at the end of their shift without paying them for that time. (If anyone besides your employer did this, we would call it false imprisonment.)

As we’ve seen over the past few years, a strike is the most powerful workplace action a union can take, and a credible strike threat one of its most powerful bargaining chips. That is why most collective bargaining agreements have “no-strike clauses,” in which the union agrees not to call a strike during the term of the contract in exchange for other benefits (often binding arbitration). It is illegal for a unit with a “no-strike clause” to go on strike unless the employer commits “serious” unfair labor practices.

Other steps can also be powerful, especially if they put pressure on supervisors who are stuck between the workers and management. But these actions are only protected under certain conditions.

Restrictions on Workplace Actions as Political Speech

In the context of action on something like the genocide in Gaza, the most important restriction on unions is the ban on “secondary boycotts.” A secondary boycott is when a union uses concerted action (strikes, picketing, boycotts, etc.) to either pressure someone besides the primary employer into action, or to pressure the primary employer to take action against another party. The only exception is that employees are allowed to honor a lawful strike or refuse to cross a lawful picket line.

What makes this ban so important is that not only are secondary boycotts illegal — but they are the only unfair labor practice I’m aware of that allows someone to bring a case directly to court instead of going through the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB). This is a huge thumb on the scale in management’s favor.

So under Supreme Court precedent, a labor union refusing to handle goods or striking until an employer divests from Israeli companies or war manufacturing would be illegal and put the union on the hook for damages. In Longshoremen v. Allied International, for instance, the International Longshoremen’s Association refused to handle cargo coming to or from the Soviet Union in protest of the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan. Allied was a company that imported goods from the Soviet Union; Allied had hired a shipping company called Waterman to ship its goods, and Waterman hired John T. Clark and Son, which was under a contract with the longshoremen, to unload its ships. The Supreme Court held that the longshoremen’s actions were an illegal secondary boycott, and that the union had to pay damages to Allied.

Less than three months later, however, the court held that a boycott of white businesses by a local National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) branch seeking equal rights in the community was a valid exercise of First Amendment activities. Under US law, the First Amendment simply does not exist within the employer-employee relationship.

If a union today refused to handle goods (including war materials) heading to or from Israel in protest of its genocide of Palestinians, there is no doubt the court would reach the same conclusion it did in Longshoremen. This means that, while the refusal or strike may send a powerful message in the short term, the companies profiting from the genocide would ultimately suffer no loss — their bloodstained profits would be covered by the legal damages and paid for by union-member dues.

There are, of course, less dramatic — and typically less powerful — actions that unions can take. But while the NLRB is generally more protective of workers than the Supreme Court, the board still requires a nexus between working conditions and what workers are protesting. In Eastex, Inc. v. NLRB, the Supreme Court upheld an NLRB ruling that a union distributing a flyer that included political messaging (opposing right-to-work laws and condemning President Richard Nixon’s veto of a minimum-wage increase) was protected by the NLRA. The court held that these issues were related enough to employees’ working conditions to be protected.

Earlier this year, the NLRB issued a decision in Home Depot that held that employees putting “BLM” (for “Black Lives Matter”) on their company-issued uniform aprons was protected activity because there was a nexus between the BLM movement at large and the racial discrimination by management and supervisors that employees were protesting. This is the most expansive ruling yet on what messages employers must allow employees to express at work — and even then, the expression was allowed only because it was related to specific working conditions at that store.

The Path Forward

There is little hope that unions will be legally able to directly engage in broader politics via workplace actions anytime soon. Passage of the PRO Act would make secondary boycotts legal, but that does not mean they would be protected — employers could still legally fire employees who participate in them And while in Eastex the court gave an opening for unions by saying that workers are protected when they seek to change conditions for workers generally or when they act on behalf of other workers to build solidarity for future disputes, it is hard to see many courts applying that logic to Palestinian workers.

But there are other ways unions can support the people of Palestine, which some unions have made use of. When universities use force against protests that include workers, they may be turning a geopolitical issue into a workplace one. UAW Local 4811, which represents forty-eight thousand grad students and academic workers in the University of California system, has gone on strike in response to the working conditions created by the university’s crackdown on the peaceful protesters. The local’s strike vote announcement cited unsafe work conditions caused by the university failing to stop mob violence against the protesters and calling in the police to violently disperse their encampments.

Other unions have filed unfair labor practice charges based on unilateral changes in work rules and policies (like changes to free speech and expressive conduct policies aimed at the antigenocide protesters) and the creation of unsafe work conditions. These charges, if upheld by the NLRB, would be massive wins for unions. Strikes against unfair labor practices have a special status in labor law: while a worker engaged in an economic strike can be permanently replaced, a worker striking over unfair labor practices must be reinstated even if the employer hired a permanent replacement for them during the strike.

US labor law outlaws and discourages unions from acting on issues bigger than the workplace. Still, if the last few years have taught us anything, it is that labor can find a way. When an effective tactic is outlawed, unionists can develop new tactics. But one thing that has never changed is that capitalists need workers a lot more than workers need them — and when workers find ways to wield that collective power, they can win big changes.

Stephen R. Keeney is a former union staff representative who currently works as a union-side labor lawyer at Doll, Jansen & Ford in Dayton, Ohio, where he is a member of the Union Lawyers Alliance.

But it’s also necessary to take a step back and acknowledge that any ambitious strategy for unionizing millions will entail lots of losses along the way. There’s an obvious way this is true: labor movements that don’t try to organize the unorganized — or that don’t go on risky strikes — never experience any big losses, they just steadily decline into irrelevance. If you unionize and strike more, your total number of losses will also rise, all other things being equal.

The point I want to make in this article, however, is more specific and less intuitive: ambitious labor movements that try to win widely actually lose a higher percentage of battles than do most unions today. Winning big and winning at scale require taking many more risks and relying less on staff. And this generally entails a higher loss rate.

As I’ll show below, one of the reasons why labor’s win rate in union elections has been so exceptionally high over the past two decades is that exceptionally few unions are seriously pursuing new organizing. And those that do are often only taking on and sticking with drives that they’re very confident will win. Any chance labor has at making a big breakthrough — any chance at decisively reversing decades of decline — requires being okay with more losses along the way.

Look at the Data

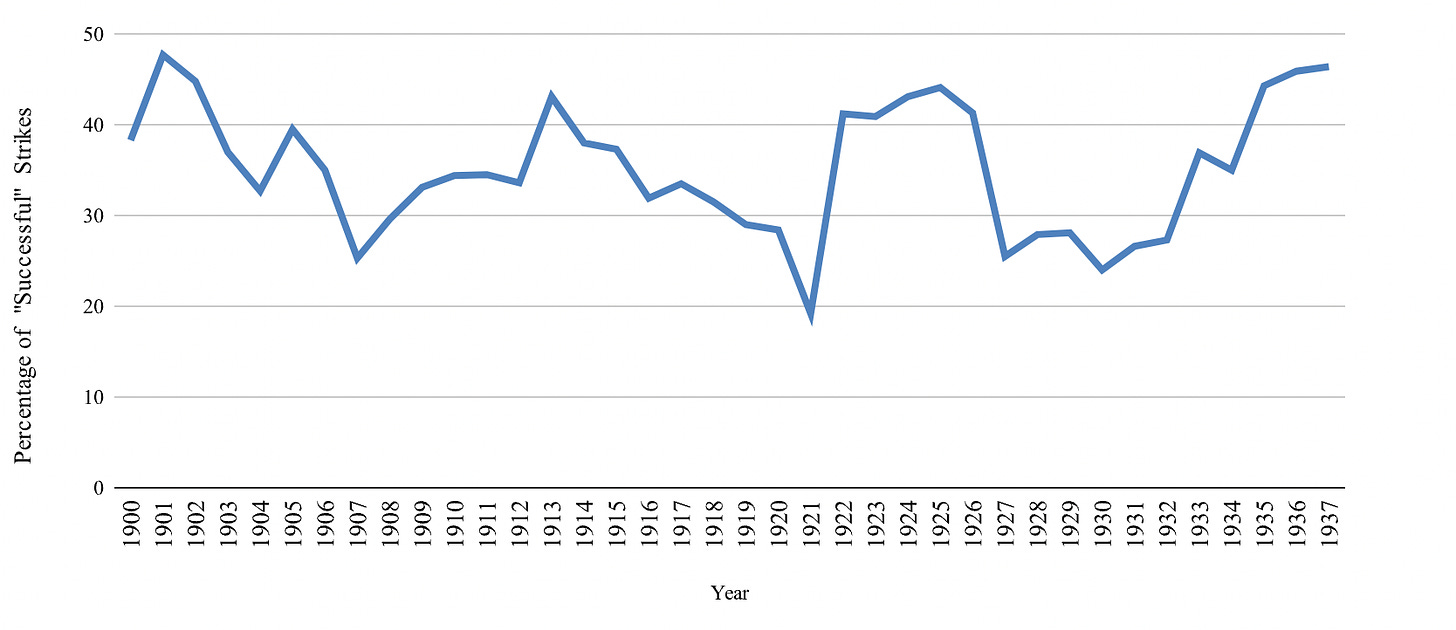

It’s helpful to compare labor’s current win rates with those of a century ago. Organized labor in the early 20th century not only waged far more battles than today, it lost these more frequently. Though there are no records of unionization win rates back then, we can compare the success rates of strikes, as compiled by government statisticians based on whether most major demands were won. As you can see in Figure 1, there wasn’t a single year from 1900 to 1937 (the last year we have data on) where a majority of strikes were “successes.”

Figure 1: US Strike Success, Yearly

Figure 1: Source: John I. Griffin, Strikes: A Study in Quantitative Economics (New York: Columbia University Press, 1939), 91, based on government reports.

National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) data from the 1960s onwards show that unions tend to win a higher percentage of elections when they organize significantly less. This makes sense, because if you only undertake unionization efforts with a high likelihood of success, your universe of potential drives shrinks considerably.

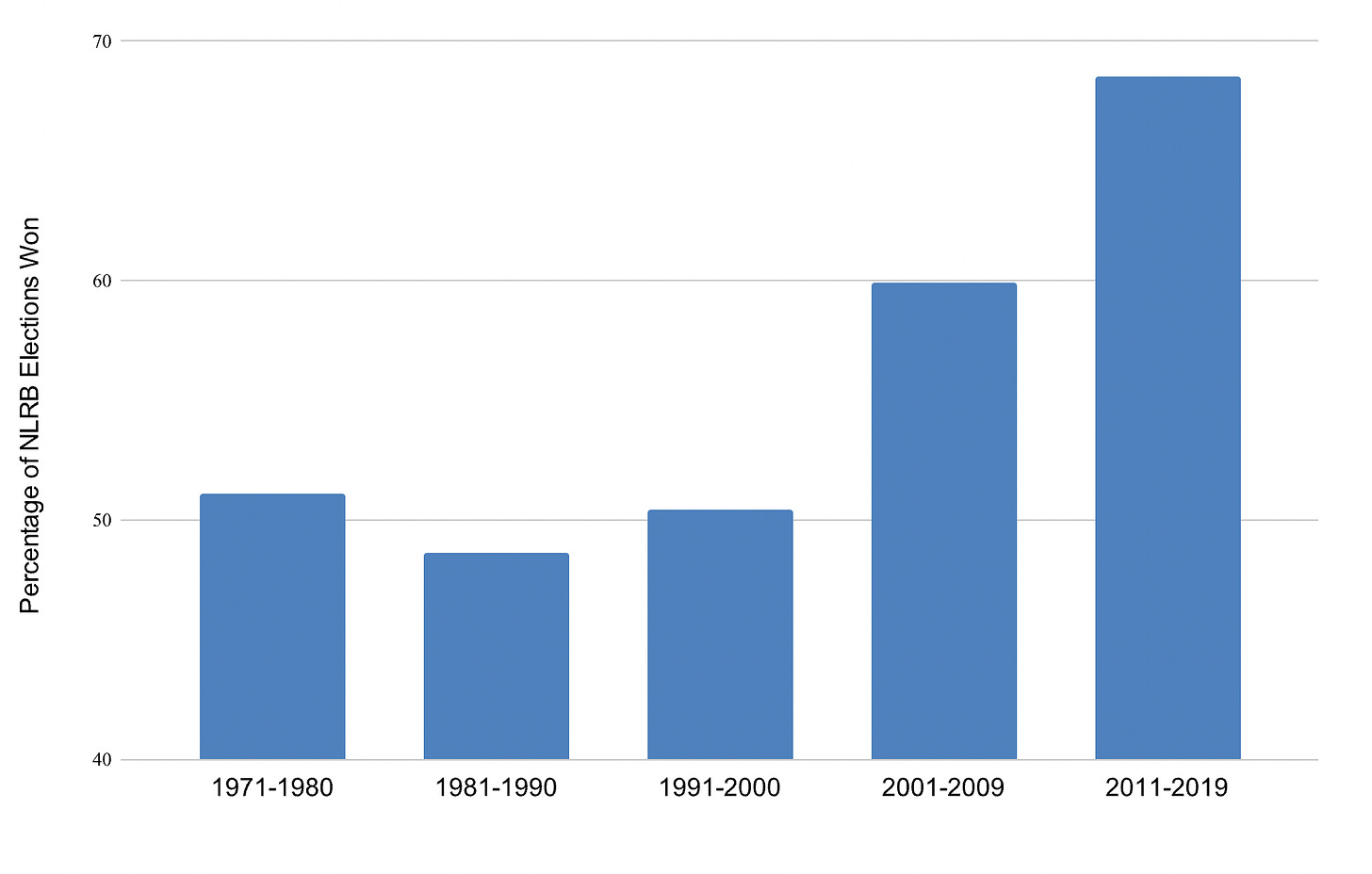

As recently as 1976-1980, unions ran about five times as many NLRB drives yearly as they do today, but their win rate was only about 48 percent. In contrast, as the total number of drives have plummeted in recent decades, labor’s win rate has steadily crept upwards, hovering at around 70 percent in recent years.

Were labor today to double or quadruple its amount of drives, the total number of union wins would shoot up even if success rates dropped back down to 1970s or 1920s levels. Winning at scale will very likely require losing more.

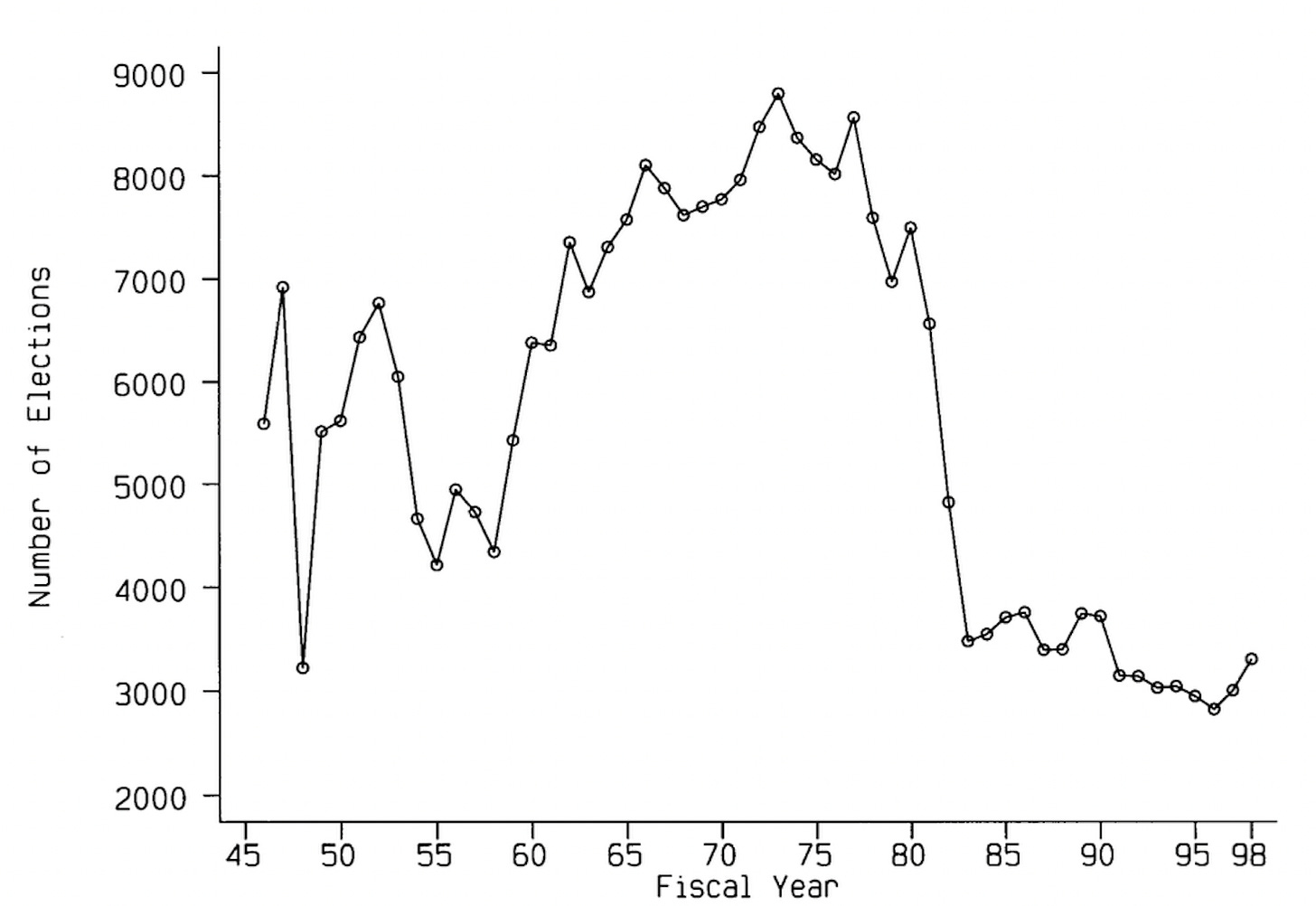

A visual depiction of these dynamics may help drive the point home. After US employers went on the offensive from 1981 onwards, the total amount of union drives plummeted and it has not yet to come close to recovering (see Figure 2).

Figure 2: Number of NLRB Certification Elections Yearly

Source: Henry Farber, “Union Success in Representation Elections: Why Does Unit Size Matter?” ILR Review 54, No. 2 (2001), 26, based on NLRB data.

One might expect that union win rates would have similarly plummeted after 1981, since bosses were fighting harder to prevent workers from winning. But, to the contrary, union win rates have steadily risen from the early 1980s onwards, as demonstrated in Figure 3. Unions started avoiding many of the hardest battles and there were fewer overall attempts to organize. But those drives that were attempted tended to win more frequently.

Figure 3: Union Win Rate, NLRB Elections

Source: Compiled by author on the basis of NLRB data as well as Lawrence Mishel, Lynn Rhinehart , and Lane Windham, “Explaining the Erosion of Private-Sector Unions” (Economic Policy Institute, 2020).

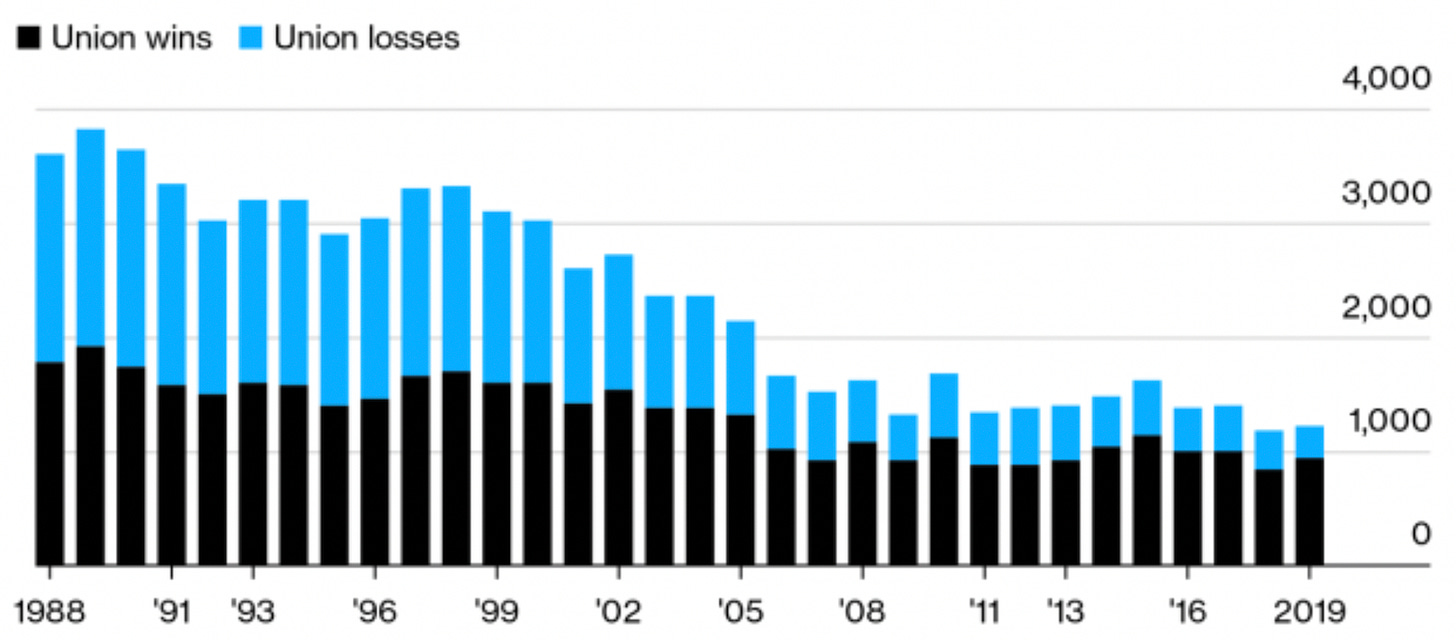

We can also see this same general trend — fewer attempted union elections usually equals a higher win rate — in the yearly data going back to the 1980s.

Figure 4. NLRB Election Results

Source: Robert Combs “Deceleration Defines 2019 State of the Unions” (Bloomberg Law, 2020)

How We Got Here

It’s obviously better for workers to win than to lose. And it goes without saying that organizers should do everything possible to win every battle, which requires (among other things) taking organizing methods very seriously and leaning as much as possible on the best practices of deep organizing. That said, post-Reagan unionism generally reflects a fear of losing that bleeds into excessive risk aversion.

This trepidation is based on real accumulated experience since the 1980s. Lost campaigns have subjected workers to employer repression, prevented further drives at demoralized workplaces (or companies) for years to come, discouraged parent unions from maintaining funding for new organizing, and hurt the reputations (and job prospects) of staffers as well as elected leaders. Lost strikes, similarly, can have devastating effects. And because new organizing since the 1980s has been so resource intensive — contemporary best practice has been to hire one staffer for every 100 workers to be organized — unions are incentivized to only take on a select number drives that they’re pretty sure will win. That’s why unions routinely say no to workers who reach out for organizing support. “Our message to the working class is ‘don’t call us, we’ll call you,’” a researcher from one such union only half-jokingly told me.

This is one of the many reasons why a worker-to-worker organizing model, as attempted at Mercedes in Alabama, is pivotal for winning widely. Part of the explanation for why the labor movement a century ago was less scared of losing was that it was far less staff-intensive — averaging 1 staffer for every 2000 workers, a ratio replicated at Mercedes. Full-time leaders and staffers will always face stronger pressures not to jeopardize, via risky actions, the health of the union that employs them. And the more expensive it is to unionize, then (all other things being equal) the less likely it is for unions to engage in new organizing. A more bottom-up model is necessary to get labor to start embarking down the risky road of waging exponentially more battles.

At its rank-and-file oriented best, staff-intensive unionism can win significant battles. But it can’t win the war. The reason for this is simple: heavily staffed organizing is too costly to scale up — i.e. to win at the widest scope necessary. Staff-intensive unionism can’t hire enough organizers, or train enough of them quickly enough in high-momentum moments, to unionize tens of millions of workers.

In other words, scaling up requires betting more on worker leaders, even if this means a relatively higher percentage of drives may end up losing. It’s less risky to depend on staff-heavy campaigns than it is to wager on bottom-up, lightly-staffed drives like Mercedes.

Faced with high stakes and powerful opponents, caution can be useful — but only up to a certain point. An excessive fear of losing is a key reason why unions have been so hesitant to seize the post-pandemic organizing opening, because unions remain deeply risk averse and because a sizable number of today’s union leaders were burned by defeats in the 2000s and don’t want to repeat the experience. It’s a much safer bet to take on only the relative handful of drives that are very likely to win, rather than shooting for the moon — as the crisis of our labor movement, our society, and our planet demands.

Different Ways to Assess Victory

Too much fear of losing can also reflect narrow strategic viewpoints. Things look differently when you’re assessing the health of the workers’ movement as a whole, not just your particular union local, and when you assess outcomes not just by what you win from employers, but also by how much solidarity, capacity, and consciousness you forge in struggle.

Defeated efforts can sometimes strengthen the overall national movement if the fight inspires others. For instance, even though the spring 2021 hot shop drive at an Amazon warehouse in Bessemer, Alabama lost its election, it played an important role in boosting the labor zeitgeist and in inspiring other Amazon workers to start organizing.

And while first contracts are an essential goal, they’re not the only ways to judge short-term success. UAW president Shawn Fain was right to highlight the major advances Mercedes workers have already wrested through their unionization effort:

Workers won serious gains in this campaign. They raised their wages, with the “UAW bump.” They killed wage tiers. They got rid of a CEO who had no interest in improving conditions in the workplace. Mercedes is a better place to work thanks to this campaign, and thanks to these courageous workers. … There are more than 2,000 workers at Mercedes in Alabama who want to join our union. They aren’t going away. The sun will rise, and the sun will set, and our fight for justice for the working class will continue.

Conclusion

Becoming less fearful of defeat — and adopting a more expansive view of what constitutes a win — is an important step towards taking more risks, adopting new worker-to-worker techniques, and massively funding new organizing projects like the UAW’s $40 million campaign to unionize the South.

Put simply: the available evidence strongly confirms the case made by UAW’s communication director Jonah Furman after last week’s loss:

What I know: only 6 percent of private sector workers are in a union in this country. We’re not gonna change that by playing it safe. We’re gonna lose a lot of battles along the way. What’s gonna sustain us isn’t a glide path to victory. It’s something deeper than any one vote. And all your best laid plans and theories and handbooks are nothing compared to real life experience. Trying stuff. Taking risks. Trying again.