The Latin American left amid China, the United States, late progressivism and the far right

First published at CADTM.

Claudio Katz has just published a book in Spanish entitled America Latina en la encrucijada global (Latin America at the Global Crossroads).1Claudio Katz is a Marxist economist and professor at the University of Buenos Aires, author of some fifteen books concerning the Dependency theory fifty years after its emergence, imperialism today, and issues faced by the Latin American Left. His new book concentrates on Latin America and deals with the continent’s relations with China and with US imperialism.

The book is in five parts: in Part 1 Katz analyses the strategy of American imperialism from the beginning of the 19th century to the present day. He demonstrates that American imperialism underwent a rising phase during which it replaced former colonial powers such as Spain and Portugal during the 19th century and Great Britain from the end of the First World War onwards. Now, after totally dominating Latin America, US imperialism has gone into decline, in particular with the rise of China as a great power. In this first part, Katz also analyses China’s policy in Latin America and the attitude of the dominant classes in Latin America toward the new great power.

The second part of the book focuses on the characteristics of the far Right in Latin America, its specific nature and the way it operates. That section concludes with an analysis of the phenomenon of Javier Milei, who became president of Argentina in late 2023.

The third part of the book looks at the experiences of the new progressivism that emerged from the major popular mobilizations that shook several parts of Latin America in 2019.

The fourth part looks at the debates within the Left about these new progressive governments and also looks specifically at what Claudio Katz sees as the four countries that make up an “alternative axis” to US imperialism — Venezuela, Bolivia, Nicaragua and Cuba.

The fifth part looks at new forms of popular resistance in recent years and addresses the question of alternatives.

The United States and China vis-à-vis Latin America

As Claudio Katz shows, the United States still has a dominant position in Latin America. According to Katz:

Between 1948 and 1990, the US State Department participated in the overthrow of 24 governments. In four cases, American troops were deployed; in three cases CIA assassinations were the means used; and in 17 cases coups d’état were directed from Washington. (Katz, p. 49)2

The US has military bases in several countries, including Colombia, where nine US bases are located. But there are also US bases in the south of the continent (two in Paraguay). The US fleet is prepared to intervene all around Latin America, on both the South Atlantic and Pacific coasts.

The United States has twelve military bases in Panama, twelve in Puerto Rico, nine in Colombia, eight in Peru, three in Honduras and two in Paraguay. They also have similar facilities in Aruba, Costa Rica, El Salvador and Cuba (Guantánamo). In the Falkland Islands, the US’s partner Britain provides a NATO network link to sites in the North Atlantic. Katz, p. 50.3

At the same time, Claudio Katz shows that since the 2010s, China has succeeded in competing with US interests in Latin America and the Caribbean with an investment policy that allows for company takeovers and a very dynamic and massive credit policy. Just what are we talking about here? In fact, the United States succeeded in convincing Latin American governments, particularly from the second half of the 19th century and throughout the 20th century, to sign free-trade agreements. Since the United States had an economy that was far more technologically advanced than the countries of Latin America, thanks to these treaties it systematically won out over local producers — capitalists in industry and agribusiness, but also small agricultural producers. American products were superior in terms of productivity and technology, and therefore more competitive.

But the United States is an economic power in decline, whereas China is booming. Compared with the economies of Latin America, but also with the United States, China now has an advantage in terms of productivity, and therefore in terms of competitiveness, in a number of technological areas. And China is now using the same economic tools that the United States used systematically — i.e. signing bilateral free-trade treaties with as many Latin American and Caribbean countries as possible. Meanwhile the United States’ proposed free-trade treaty for all the Americas (the FTAA), whose provisions ensured US domination, was rejected by a whole series of South American governments in 2005. Since then, the US’s economic decline in relation to China has accentuated, and it no longer has the means to try to convince countries in the South to sign free-trade agreements. Above all, the US is no longer in a position to really benefit from such agreements, because of competition from China. As a result, it is China that favours the dogma of free trade and the mutual benefits to be derived by the various economies if they adopt this type of agreement. China benefits from this because, as Claudio Katz rightly points out, its products are much more competitive in Latin America than the products made by Latin American economies or by the United States, and the products exported by Latin American economies to China are essentially raw materials, minerals and transgenic soybean. As a result, they are not really competitive with Chinese products. China is reaping the full benefits of the type of relationship it is developing with Latin American countries, gaining market share in their domestic markets at the expense of local production. We are witnessing a re-primarization of economies, and this can be seen very clearly in the type of products exported from Latin America to the world market, particularly to China — which is becoming the biggest trading partner of several Latin American countries, Argentina and Peru being two examples.

Claudio Katz demonstrates that China derives maximum benefit from Latin America because Latin American governments are incapable of devising a common policy and an integration policy that favours the development of the domestic market and local production for that domestic market.

He points out that China does not behave entirely like a traditional imperialist country; it does not use armed force. Unlike the United States, China does not accompany its investments with military bases.

As mentioned above, Claudio Katz lists the military aggressions carried out by the United States in Latin America — a list that is obviously impressive and in stark contrast to China’s behaviour towards Latin America and the Caribbean. As he correctly points out, China has not become an imperialist power in the full sense of the word (unlike Russia, in my own view). He argues that capitalism is not fully consolidated in China. Does he mean that the Chinese leadership could make a U-turn and move away from capitalism? Frankly, that is doubtful. He also repeats the claim that economic development in China has lifted 800 million people out of poverty, without explaining on what basis he makes this claim: what studies? what figures? In order to talk about 800 million people being lifted out of poverty, we would need to specify in relation to which year, to which year’s population, and say on what basis the poverty line is determined.

This is a very important question, and Katz’s argument is woefully lacking in foundation. The figures he gives are those given by the World Bank and the Chinese authorities, and I have shown in several articles that the World Bank’s assessments are highly questionable. In fact, the World Bank itself admitted in 2008 that it had overestimated the number of people lifted out of poverty by 400 million.

In the absence of any references from Claudio Katz, we can only wonder whether he is basing his claim on World Bank figures without saying so and, if not, what statistical data he is using. He would do well to provide the necessary details, as this would strengthen his argument.

On the other hand, Katz has no difficulty in acknowledging that a major capitalist class has been re-established in China, and he criticizes those who say that China is at the centre of the socialist project of our time. He says that this capitalist class has ambitions to regain power. Katz believes that socialist renewal is possible; that invites the question of whether it can come from the CCP leadership. I think we have to make it clear that the answer is no: socialist renewal will not come from the CCP leadership.

Claudio Katz is also right in saying that China is not part of the global South. He writes:

All the treaties promoted by China reinforce economic subordination and dependence. The Asian giant has consolidated its status as a creditor economy, taking advantage of unequal trade, capturing surpluses and appropriating revenues.

China does not act as a dominating imperial power; but neither does it favour Latin America. The current agreements exacerbate primarization and the flight of surplus value. The external expansion of the new power is guided by the principles of profit maximization, not by norms of cooperation. Beijing is not a simple partner and is not part of the South. (p.73)4

The myth of the success of neoliberal policies

In the second part of his book, Claudio Katz begins by attacking the policies of Latin American neoliberals and shows how their being in power — as they are in several countries today — has not led to any real progress for the continent.

Katz shows that the so-called success of neoliberal policies in Latin America is nothing more than a myth, since the ruling classes and the governments that serve them continue to be subservient to US imperialism, but are also opening up to China’s policies, which the US frowns upon while failing to offer Latin America a genuine alternative in terms of economic and human development. What interests China is the possibility of exploiting the continent’s raw materials to feed the “world’s factory” China has become, and then re-exporting its manufactured products to various markets, including the Latin American market.

Katz shows that poverty remains very high in Latin America, and is even increasing, affecting 33% of the population. Extreme poverty affects 13.1% of the population, while inequality is increasing in favour of the richest 10%.

Economic growth is very slow if we consider the rate of growth over the period 2010—2024, which was 1.6% per annum. This is lower than the period 1980—2009, when growth reached 3%, and the period 1951—1979, when it reached 5% annually.

Katz then looks back at the Latin American independence movements, most of which arose in the 1820s. He shows that independence only led to a new type of subordination to new powers: firstly Great Britain, which was struggling to conquer its own space at the expense of Spain and Portugal, and then, from the end of the 19th century, the United States. I should point out that I addressed this question in my book The Debt System,5in which I devote several chapters to the 19th and early 20th centuries, and in which I demonstrate that it is both the free-trade agreements and the type of indebtedness in which the governments of Latin American countries have become entangled that have led to a new cycle of dependence/subordination, with the fundamentally harmful role played by the ruling classes, who are accomplices of the various new imperialisms.

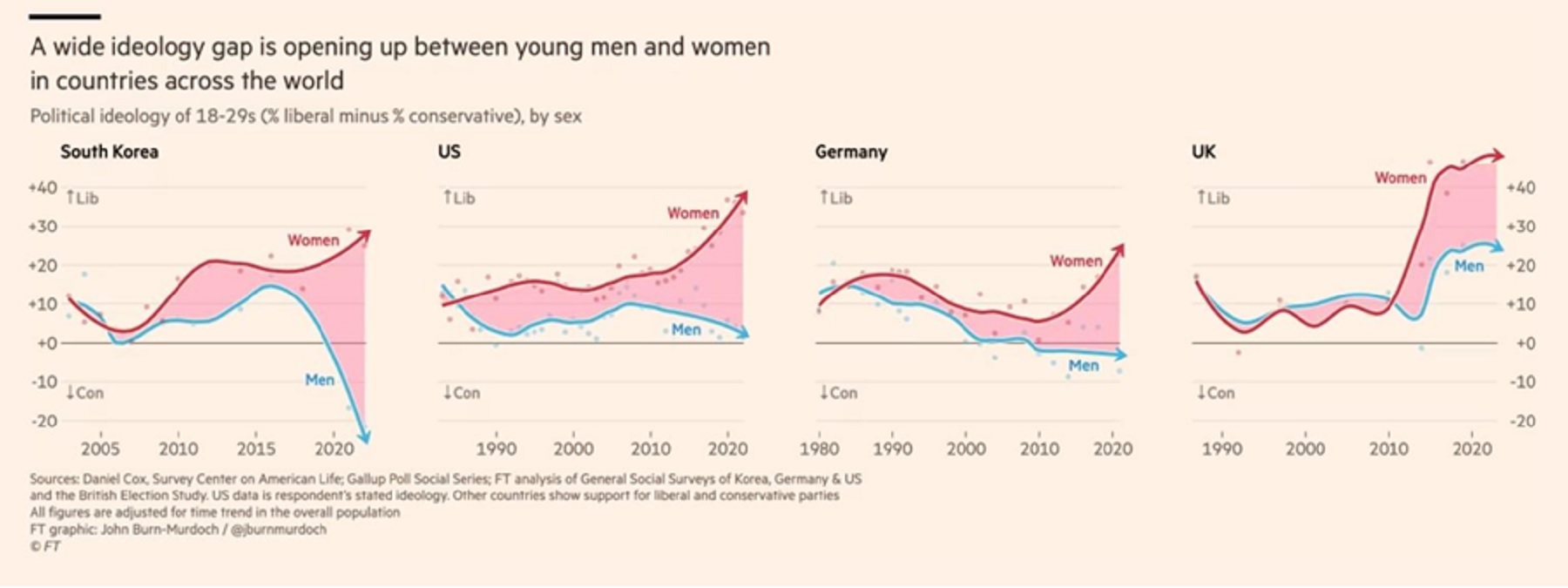

The rise of the far right in Europe and Latin America: Specificities and similarities

Then, still in Part 2, Claudio Katz takes a very interesting look at the rise of the far Right in Latin America. To show the specific nature of this rise, he begins by analysing the characteristics of the far Right in Europe and of its growth. He then analyses the specific characteristics of the far Right in Latin America: unlike the far Right in Europe or the United States, it does not put the issue of immigration at the centre of its rhetoric — although in some countries, such as Chile, it does raise the spectre of the “danger” that migrants represent. But this is not a general trend, as it is in Donald Trump’s speeches and in the rhetoric of the different variants of the far Right in Europe, including those in government — for example Giorgia Meloni in Italy, Viktor Orbán in Hungary, the RN in France, AfD in Germany, VB and NVA in Belgium, FPÖ in Austria, etc.

In Latin America, the far Right, for example in Bolivia and Peru, uses a racist discourse that is directed against the indigenous majority, the native peoples, rather than against migrants. The spectre of the “communist threat,” in the form of Castro, Chavism and other Latin American experiments in which the radical Left has made gains, is another theme found more often in the rhetoric of the Latin American far Right than it is in Europe. This is because in Europe, over the last fifty years, the direct threat to the Right of socialist-oriented experiments has not been as tangible as in Latin America. Katz also shows the importance of evangelical movements, which are extremely reactionary, and of the claim by the Latin American far Right of the supremacy of white populations of European, and especially Iberian, origin. The Latin American far Right magnifies colonization since Christopher Columbus as a civilizing achievement, which explains the close connections between the far Right in several Latin American countries and the Vox party in Spain, which does the same.

Katz also shows that in some cases, the far Right has demonstrated a capacity for mass mobilization. A notable example is Bolsonarism, which succeeded in taking over Brazil’s government in 2019 until Lula da Silva’s re-election to the presidency at the end of 2022. And Bolsonarism retains that capacity for mass mobilization despite its electoral defeat, as it demonstrated in February 2024, when almost 200,000 people gathered in São Paulo.

Extremely harsh repression of the “dangerous” classes and of delinquents is an important aspect of the rhetoric of the Latin American far Right. Such is the case with the government of Nayib Bukele in El Salvador,6which has carried out numerous extrajudicial executions and created the largest prison in Latin America in the name of the fight against drug trafficking. Another example is Jair Bolsonaro’s use of militias in the poor districts, in particular in Rio de Janeiro.

The second part of Claudio Katz’s book also contains a reflection on fascism and the far Right today. I’m not going to go into detail about the concepts Katz uses; I’ll leave it to the reader to discover what is a highly interesting contribution in this area.

Then, still in Part 2, Katz examines the politics of the far Right using a number of examples from different countries. He takes the example of Bolsonaro’s Brazil and of Bolivia, followed by Venezuela, Javier Milei’s Argentina, Colombia and Peru, followed by a few paragraphs referring to Nayib Bukele in El Salvador and the situation in Ecuador and Paraguay.

Among the explanations for the rise of the far Right is of course the disappointment of a sector of the working classes with their experiences with progressive governments; but there is also the impact of American imperialism, the activity of the evangelical churches and the lack of a firm reaction to the threat of the far Right by progressive governments. Katz shows that when there has been a very strong reaction, as in Bolivia, it has produced results.

The new wave of Latin American progressivism: moderate late progressivism, often brought to power by large-scale mobilizations

In Part 3, Claudio Katz looks at the experiences of progressive governments. He begins by noting that there was a progressive wave that began in 1999 and ended in 2014. It was followed by a conservative backlash that provoked popular mobilization in several countries and led, especially from 2021—2022, to a new progressive wave. He stresses that this new progressive wave is a step back from the 1999—2014 period in that progressive governments are pursuing much less radical policies than those of Hugo Chávez in Venezuela (1999—2012), for example, or Evo Morales in the first period of his presidency in Bolivia (2005—2011) or Rafael Correa in Ecuador (2007—2011). This less radical progressive wave is affecting countries that were not affected by the previous wave — namely Mexico, Colombia since 2022 with the government of Gustavo Petro, and Chile with the government of Gabriel Boric.

Katz successively analyses the very recent — since early 2023 — the return of Lula to the presidency of Brazil and the election of Gustavo Petro as president of Colombia. He reviews Alberto Fernández’s term as president of Argentina from 2019 until Javier Milei’s victory at the end of 2023. He analyses the policies of Andrés Manuel López Obrador (AMLO) in Mexico since 2018, those of Gabriel Boric in Chile and, finally, those of Peru’s Pedro Castillo, who was overthrown in 2022.

I fully agree with Katz’s assessment of the governments I have just mentioned, and I recommend that you read this section.

To sum up, what stands out about the progressive governments of the 2018—2019 period, in the case of Mexico and Argentina, and then of the 2021—2022 period for Brazil, Colombia, Chile and Peru, is their lack of radicalism; they are fully maintaining the agro-export extractivist model, and no free-trade treaty has been abrogated. Katz is particularly harsh in his criticism of Gabriel Boric’s government in Chile and Pedro Castillo’s in Peru. I leave it to readers to read his arguments, which I very much share.

Lula’s international policy

In Part 3, Claudio Katz then looks at the international and regional policies of several progressive governments, and in particular the most economically important one: Brazil’s. He discusses Lula da Silva’s support for the treaty between Mercosur and the EU. One of the reasons why Lula is pushing to reduce deforestation in the Amazon is to meet the demands of the EU, which is under pressure from European industrial lobbies but also from protests in European countries by social movements and farmers, who cite unfair competition from Brazilian exporters. Environmental demands are being put forward, and of course Lula wants to reduce deforestation due to pressure from the indigenous peoples of Amazonia and environmental movements, but he is all the more convinced of the need to do so because it is an EU demand and he wants to implement the Mercosur-EU treaty.

I would add that the Left in Europe is opposed to this treaty. It should also be pointed out that left-leaning social movements and environmentalists, as well as the native peoples’ movements of Latin America and the Mercosur countries, have been opposing the signing of the treaty, which is still being negotiated, for years.

Claudio Katz also explains that the Lula government wants to adopt a non-dollar currency of account between Mercosur countries in order to reduce the use of the dollar. Lula’s idea is to import liquid gas via a pipeline that would run to the southern border of Brazil and then on to Porto Alegre, replacing Brazil’s supply of gas from Bolivia, since Bolivian reserves are drying up at an accelerated rate. This is important for strengthening economic relations between Argentina and Brazil, because Argentina lacks foreign-exchange reserves, and Brazil, which exports heavily to Argentina, needs for Argentina to be able to buy its goods — particularly under pressure from Brazil’s major industrial capitalists, heavily invested in auto manufacturing and for whom the Argentine market is important. Therefore the adoption of a unit of account within Mercosur, and in particular between Argentina and Brazil, would enable Argentina to do without dollars, which it does not have in sufficient quantity, in purchasing products imported from Brazil. Lula’s Brazil is also interested in exploiting the Vaca Muerta gas field in Argentina, which is opposed by social, left-wing and environmental movements in that country.

Katz also explains that Lula would like to bring Bolivia and Venezuela into Mercosur.

Note that in this book Claudio Katz makes no use of the theoretical contribution of the Brazilian Marxist economist Rui Mauro Marini on the subject of Brazilian sub-imperialism or peripheral imperialism and its role in relation to its neighbours. Katz has done this in other works, but it might have been a useful tool for the readers of this book. A second omission from Katz’s book (admittedly he can’t write about everything) is BRICS, Brazil’s role therein and Lula’s expectations regarding BRICS. The role of BRICS, the question of whether or not to adopt a common currency, and the role of the new development bank based in Shanghai — which is chaired by the former president of Brazil, Dilma Rousseff, who succeeded Lula — are not marginal aspects of the overall problem addressed by Claudio Katz in his book. I feel that they would have deserved fuller development.

The limits of the policies of progressive governments

Then, still in Part 3, after discussing Mercosur policy, free-trade treaties and the economic relationship with the United States, Claudio Katz returns to China’s policy in Latin America in a highly interesting section that I don’t have time to summarize here, but which contains important information. I also agree with him that the progressive governments have not at all taken a position commensurate with the challenge posed by the issue of debt and the need to audit the debts claimed on Latin America. And I agree that Lula’s Brazil, during Lula’s first terms of office in the early 2000s, sabotaged the launch of the Bank of the South. In a recent article of mine on this subject, I went into detail about Lula’s sabotage of the launch of the Bank in the years following 2007—2008, and so I fully share Katz’s analysis of the issue.

As to the question of alternatives, Katz argues that if progressive governments really wanted to try to implement an alternative to the neoliberal extractivist export model on the continent, they should work together to create a Latin American public company to exploit lithium.

Katz also argues that progressive governments should adopt a policy of financial sovereignty, extricating themselves from the current type of indebtedness and the control exercised by the IMF over the economic policy of many countries in the region. He argues that there should be a general audit of debts and that a number of the most fragile countries should suspend their debt repayments. He says that if this is not done, there will be no way of putting an alternative in place, and he argues that the Bank of the South should again take up the path it was on, toward creating a new continental architecture. Here again, I can only share his point of view.

Debate in the Latin American left

In Part 4 of his book, Claudio Katz addresses ongoing debates within the Latin American Left, in particular over the attitude that should be adopted towards the Right and far Right and towards progressive governments and their limitations.

He asserts that it is a duty to express clear criticism of progressive governments... without, of course, misidentifying enemies. There is no doubt that the first thing to do is to challenge the policies of the Right and its political forces, and imperialist interventions — particularly those of the United States —, and also China’s policy in the region. But we must not limit ourselves to that. We also need to analyse and criticize, where necessary, the limits of the policies of the so-called progressive governments. Claudio Katz shows how the Alberto Fernández administration in Argentina, from 2019, bears heavy responsibility for the victory of the far-Right anarcho-capitalist Javier Milei.

With regard to these policies, I would like to quote Katz, who says:

We must remember that the left-wing option is forged by stressing that the Right is the main enemy and that progressivism fails because of weakness, complicity or lack of courage with regard to its adversary. But we must not confuse right-wing governments with these progressive governments and say that they are of the same nature. There is a fundamental distinction between the two, and if we forget that we are incapable of conceiving of an alternative and a correct policy. (p. 220) 7

This huge popular mobilization, in which CONAIE played a key role, along with other sectors of the population, did not lead to the victory of a left-wing government in the elections that followed, again as a result of the split between CONAIE and the movement linked to Rafael Correa, but instead to the victory of a multi-millionaire from the banana and extractivist sectors, Daniel Noboa.

Then there is the case of Haiti, with extremely strong, repeated mobilizations, but with a perpetual political crisis, with no solution and no arrival to power of a left-wing government.

Finally, there is Panama, with huge mobilizations in the education sector and, in 2023, huge successful movements among different sectors of the population (including teachers, but involving all working-class sectors) against a huge open-pit mining project, but which did not result in the victory of a left-wing government. In the last elections, a right-wing president, José Raúl Mulino, was elected.

Alternatives

The last part of Claudio Katz’s book deals with alternatives, and it should be noted that he rightly argues that we must resist both the domination exerted by US imperialism and the economic dependence generated by the agreements China has entered into with Latin America. Katz asserts that we need to act on these two challenges if we want to find a Latin American path to development, improve the incomes of working-class sectors and reduce inequality in the region. According to Katz these are two different battles; the two enemies are not identical, but both battles need to be fought. With regard to Washington, the task is to recover sovereignty, whereas with regard to China, the challenge is to react to what he calls a “productive regression” brought about by the treaties signed with Beijing. This “productive regression” is the re-primarization of economies: As explained above, Latin America specializes in exporting unprocessed raw materials to China, and imports manufactured goods from China. Katz believes that the free-trade agreements entered into with China should be called into question. He believes that Latin America should negotiate as a bloc with China, which is absolutely not being done at present. Currently, the governments of the individual Latin American countries, in line with the wishes of the local ruling classes, enter into bilateral agreements with the Chinese. As these ruling classes specialize to a large extent in import-export, they benefit from this, but it does absolutely nothing to diversify the Latin American economies and resume their industrialization. So, according to Katz, the agreements with the Chinese must be renegotiated so that China invests in manufacturing production and not just in the primary extractive industries. Latin America needs to reindustrialize and secure technology transfers so that a diversified industrial development cycle can be re-started.

Since current governments and the local ruling classes are not adopting an alternative policy to those determined by relations with the United States or China, we have to rely heavily on the mobilization of social movements. Claudio Katz gives the example of the positions and the actions taken by the organizations of the global network La Via Campesina, which has a strong presence in Latin America. This worldwide organization has included the rejection of free-trade treaties in its platform for action.

Social movements and international networks

Claudio Katz notes that the great mobilizations of the late 1990s and early 2000s — with the World Social Forum (WSF), the struggles against the WTO in Seattle and the struggles in Europe against the Multilateral Agreement on Investment that was being negotiated within the OECD — have unfortunately come to an end, and a whole series of free-trade treaties have been signed. It should be remembered that the protests, particularly in Latin America in 2005, resulted in a victory against the Free Trade Agreement of the Americas (FTAA) proposed by George W. Bush’s administration. Since then there have been no major mobilizations, and as part of the New Silk Road project, China has succeeded in imposing free-trade agreements with Latin American countries or is in the process of finalizing new agreements with countries that have not yet signed with China. Free-trade agreements have also been entered into with other powers.

With regard to the free-trade agreements entered into with China, Katz mentions the one signed in 2004 between Chile and China, the agreement between Peru and China signed in 2009, between Costa Rica and China in 2010 and, more recently, the agreement with Ecuador signed in 2023, with a particularly right-wing government.

In the face of this trend, Katz quite rightly says that there is a need to re-create bottom-up spaces for regional unity in order to re-launch a major dynamic of mobilization.

In terms of objectives, he correctly states that the aim is to recover financial sovereignty, which has been undermined by external debt and IMF control over economic policy. According to Katz, we need to impose a general audit of debts and the suspension of debt repayment for countries with a very high level of indebtedness in order to lay the foundations for a new financial architecture. We also need to move towards energy sovereignty by creating large inter-state entities to generate synergies and pool a broad variety of natural resources, exploiting them jointly. In particular, a Latin American public company must be created to exploit and process lithium.

Katz argues that the alternative must be a strategy of moving towards socialism. In his view, Hugo Chávez had the merit of reaffirming the relevance of the socialist perspective and, since his death, no one else has replaced him in this respect. Katz argues that a transitional strategy is needed to break with the capitalist system. He says that we must fight against US imperialism, which has embarked on a new cold war against Russia and China. He also affirms the need to fight against the far Right and against the adaptation of social democracy to neoliberal policies. According to Katz, this adaptation of social democracy has encouraged the strengthening of the far Right.

The need for a radical, revolutionary anti-capitalist transition programme

Claudio Katz calls for a “radical, revolutionary, anti-capitalist transition programme.” He adds:

This platform involves the de-commodification of natural resources, the reduction of the working day, and the nationalization of banks and digital platforms in order to create the foundations for a more egalitarian economy.

Katz starts from the observation that there is no current pattern of simultaneous or successive revolutionary victories, unlike what happened in the twentieth century with the succession of victorious revolutions in Tsarist Russia, China, then Vietnam and Cuba. Nevertheless, he believes it is important to reaffirm that only a socialist solution to the crisis of capitalism can offer a real solution for humanity. He maintains that Latin America will always be a region of the world where a renewal of the search for socialist alternatives can spring up, even if processes such as ALBA — the association including Venezuela, Bolivia and Ecuador launched by Hugo Chávez in the early 2000s — have suffered a setback.

Conclusion: An indispensable book

All in all, Claudio Katz’s book is essential reading for activists and researchers who want to understand the current political, economic and social situation in Latin America. What is interesting about Katz’s approach is that not only does he analyse the policies pursued by the governments of the major powers — the United States, China, etc. —, but also the policies of the dominant classes in the Latin American region. He studies the dynamics of social struggles and, finally, concludes that it is from below that a socialist project can be re-created.

We can only regret that the dimension of the ecological crisis and the urgency of finding solutions to it, within a socialist framework, is not sufficiently central to the book, including in the conclusions, even though it is clear that Claudio Katz supports a socialist ecologist approach. But his book would gain in strength if Katz were to develop this aspect explicitly at various points in his reasoning.

The author would like to thank Claude Quémar for his collaboration, Maxime Perriot for the final proofing and Snake Arbusto for the translation into English.

- 1

Claudio Katz, America Latina en la encrucijada global, Buenos Aires: Batalla de Ideas, La Habana: Ciencias Sociales, 2024, 366 pp, ISBN: 978-987-48230-9-0 https://batalladeideas.ar/producto/america-latina-en-la-encrucijada-global/

- 2

Entre 1948 y 1990, el Departamento de Estado estuvo involucrado en el derrocamiento de 24 gobiernos. En cuatro casos, actuaron efectivos estadounidenses, en tres ocasiones prevalecieron los asesinatos de la CIA, y en 17 hubo golpes teledirigidos desde Washington. Katz, p. 49.

- 3

Estados Unidos cuenta con doce bases militares en Panamá, doce en Puerto Rico, nueve en Colombia, ocho en Perú, tres en Honduras, y dos en Paraguay. Mantiene, además, instalaciones del mismo tipo en Aruba, Costa Rica, El Salvador y Cuba (Guantánamo). En las Islas Malvinas, el socio británico asegura una red de la OTAN conectada con los emplazamientos del Atlántico norte Katz, p. 50

- 4

Todos los tratados que ha promocionado China acrecientan la subordinación económica y la dependencia. El gigante asiático afianzó su estatus de economía acreedora, lucra con el intercambio desigual, captura los excedentes y se apropia de la renta.

China no actúa como un dominador imperial, pero tampoco favorece a América Latina. Los convenios actuales agravan la primarización y el drenaje de la plusvalía. La expansión externa de la nueva potencia está guiada por principios de maximización del lucro y no por normas de cooperación. Beijing no es un simple socio y tampoco forma parte del Sur Global. Katz, p. 73-74.

- 5

Toussaint, Eric, The Debt System: A History of Sovereign Debts and their Repudiation, Chicago: Haymarket Books (25 Jun. 2019) ISBN 1642591181

- 6

UN Geneva, In Dialogue with El Salvador, Experts of the Committee against Torture Praise Domestic Violence Legislation, Ask about the State of Emergency and Torture Complaints, 18 November 2022, https://www.ungeneva.org/en/news-media/meeting-summary/2022/11/dialogue-el-salvador-experts-committee-against-torture-praise; Human Rights Watch, ’We Can Arrest Anyone We Want’— Widespread Human Rights Violations Under El Salvador’s ‘State of Emergency’,https://www.hrw.org/report/2022/12/07/we-can-arrest-anyone-we-want/widespread-human-rights-violations-under-el; La Jornada, Bukele: la ilusión de la seguridad, 27/05/2024, https://www.jornada.com.mx/2024/05/27/opinion/002a1edi (in Spanish)

- 7

Es necesario recordar que la opción de izquierda se forja señalando que la derecha es el enemigo principal y que el progresismo fracasa por impotencia, complicidad, o falta de coraje ante su adversario. No hay que confundir la derecha en el gobierno con los gobiernos progresistas y decir que son lo mismo. Hay una distinción fundamental entre las dos opciones y si lo olvidamos, seremos incapaces de concebir una alternativa y una política correcta.(p. 220)]]

Progressivism fails because of weakness, complicity or lack of courage with regard to its adversary

To take one example, Katz explains that the inability of a part of the Left in Ecuador to see the danger represented by the election of the banker Guillermo Lasso led to the latter’s victory in 2021, whereas an alliance between the components of the Left could have led to a different result.

As a positive example, however, he shows that the Socialism and Liberty Party’s (PSOL) understanding of the importance of giving priority to combating the danger of Jair Bolsonaro’s re-election in 2020—2022, when the PSOL called for a vote in favour of Lula in the first election round, was beneficial and brought about Bolsonaro’s defeat. Because, in fact, Lula’s victory over Bolsonaro came down to very few votes, and if the PSOL had not called for a vote for Lula, it is quite possible that Bolsonaro would have been re-elected. The overwhelming majority of Lula’s votes came from his electoral base, but the PSOL made a significant contribution at the margins to give him the advantage.

At this point Katz discusses the recent (late 2023) debate within the radical Left in Argentina, part of which did not want to vote for Sergio Massa, the neoliberal Peronist candidate, against the far-Right candidate Milei in the second round. Katz is absolutely right to raise this issue and to stress the importance of standing up to the Right. Yet it is certain that even if the entire Argentine far Left, grouped together in the FIT-U, had called for a vote for the neoliberal candidate Massa, it would still not have led to a defeat of Milei, who won by a huge margin.

Regarding Chile, Katz highlights the fact that initially there was a major mobilization of the Left in 2021 to prevent the victory of the extreme right-wing Pinochetist candidate José Antonio Kast, which enabled the Left candidate Gabriel Boric to win, but that Boric’s moderation and hesitation led to his defeat in the referendum over the new draft constitution in September 2022. Boric’s interpretation of the rejection of the new constitution — which was in reality quite moderate, whereas he presented it as too radical — ultimately reinforced the Right’s rhetoric, as Boric made concession after concession to them.

Claudio Katz and the “radical axis”: Venezuela, Bolivia and Nicaragua

After analysing the policies of moderate progressive governments, Katz turns to what he calls the “radical axis.” I find this part of the book unconvincing. I don’t understand why Katz puts Nicaragua in the same category as Venezuela and Bolivia, when he himself explains that the only thing these three countries have in common is that they are under fire from US imperialism. I don’t feel that a country can be defined as part of a “radical axis” simply because Washington is working to undermine its government.

It would have been better to develop a specific category in which to include Nicaragua. Nicaragua is a country where there was a genuine revolution that led to victory in 1979. Then came an electoral defeat in February 1990, marking the start of a process of degeneration of the Sandinista National Liberation Front (FSLN) under the leadership of Daniel Ortega. This process was followed by a real betrayal of the previous revolutionary process through an alliance between Ortega and the Right — including its most reactionary components — on various issues, particularly abortion. We should also mention the pro-Washington and pro-IMF turn taken by Ortega’s government. It was in fact this submission to the IMF that led to a popular rebellion in April 2018. Until April 2018, Daniel Ortega’s regime got on very well with the United States and the IMF. It was the IMF that wanted a pension reform that led to a revolt by working-class sectors, particularly young people, which Ortega put down in an absolutely brutal manner, as Katz correctly denounces in this book and in an article dating from 2018. It was after this criminal repression of the social movement that Washington decided to take a clear stand against Ortega’s regime.

Fortunately, Claudio Katz is critical of Ortega’s repression and makes no secret of the fact that his government subsequently cracked down on any candidates who wanted to run against him in the subsequent elections. It has also put former revolutionary leaders in prison, as Katz points out and denounces. Unfortunately, he does not offer an overall analysis of what has happened in Nicaragua.