Moldova's ruling PAS party pulled comfortably ahead of its Russian-leaning rivals in a high-stakes parliamentary election as final results trickled in on Monday, leaving the EU candidate country that borders Ukraine on a path towards European integration. The tense vote was marked by a string of incidents and overshadowed by accusations of Russian interference.

Issued on: 29/09/2025 - 00:28

By: FRANCE 24

05:06

Moldova's ruling pro-EU party on Sunday topped parliamentary elections, according to almost complete results for a vote overshadowed by accusations of Russian interference in the ex-Soviet country.

The small European Union candidate nation, which borders Ukraine and has a pro-Russia breakaway region, has long been divided over whether to move closer with Brussels or maintain Soviet-era relations with Moscow.

Sunday's elections were seen as crucial for the country to maintain its push towards EU integration, launched after Moscow's 2022 invasion of Ukraine.

02:46

PAS – whose leaders did not address waiting reporters late Sunday – gained 52.8 percent in 2021.

"Statistically speaking PAS has guaranteed a fragile majority," analyst Andrei Curararu of the Chisinau-based think tank WatchDog.md told AFP.

But he warned that "the danger is not surpassed, as a functional government is difficult to form."

Curararu added: "The Kremlin has bankrolled too big of an operation to stand down and could resort to protests, bribing PAS MPs and other tactics to disrupt forming a stable pro-European government."

Call for protests

The ballot was overshadowed by fears of vote buying and unrest, as well as "an unprecedented campaign of disinformation" from Russia, according to the EU.

Moscow has denied the allegations.

16:58

Igor Dodon, a former president and one of the leaders of the Patriotic Bloc, called on people to "peacefully protest" on Monday, accusing PAS of stealing the vote.

"If during the night there are falsifications, tomorrow we won't recognise (the result of) the parliamentary elections... and we will ask for elections to be repeated," he said late Sunday outside the electoral commission, where he went with some supporters.

Earlier Sunday, voter Natalia Sandu said the election was critical becasue the nation was "at a crossroads".

"Our hope, and our expectation, is that we will stay on the European path," the 34-year-old homemaker told AFP.

"The alternative is unthinkable, I refuse to even imagine sliding back into the past," she added.

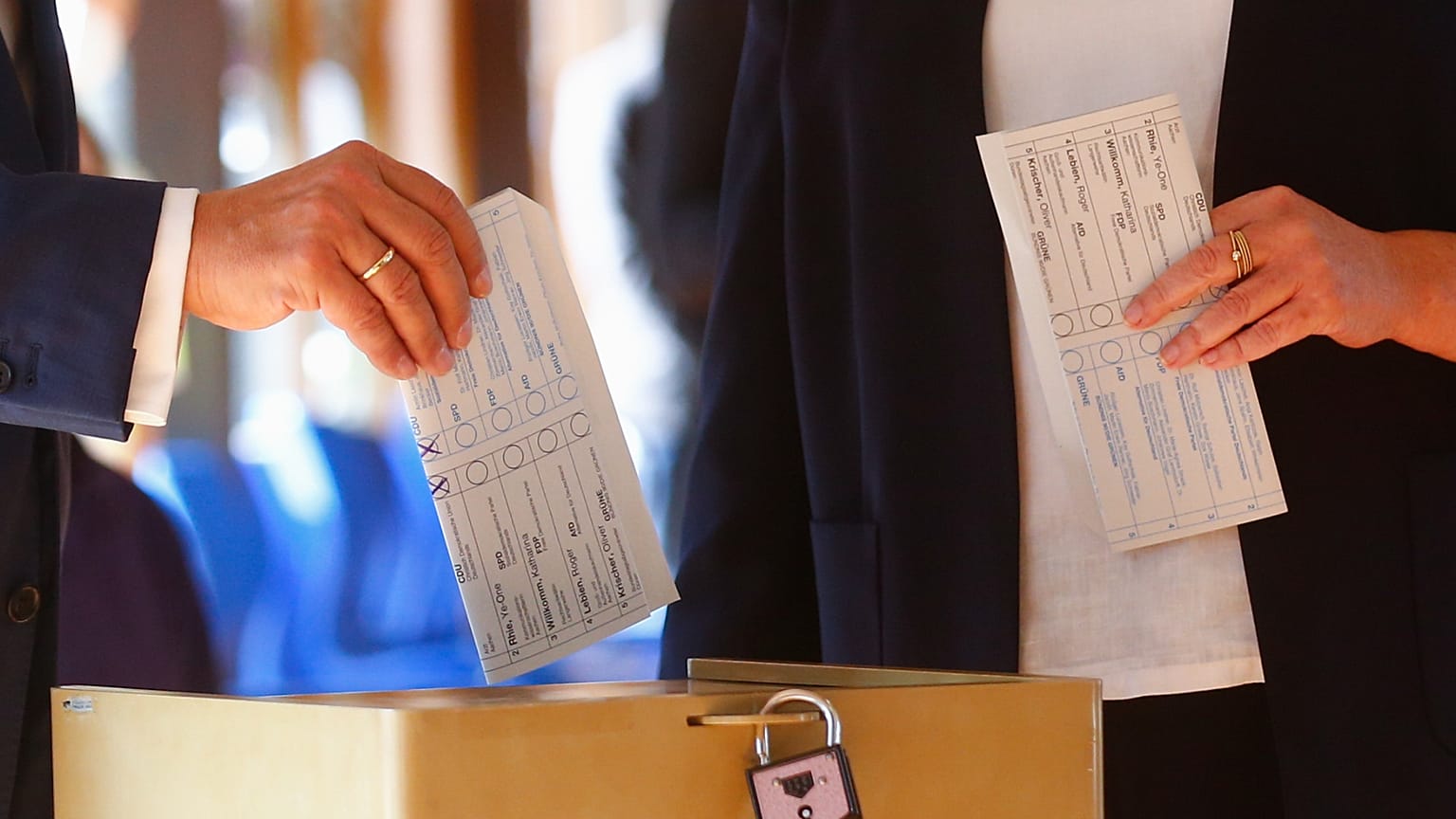

Turnout stood at around 52 percent, similar to that of the last parliamentary elections in 2021.

Voters in the country of 2.4 million – one of Europe's poorest – have expressed frustration over economic hardship, as well as scepticism over the drive to join the EU.

"I want higher wages and pensions.... I want things to continue as they were during the Russian times," Vasile, a 51-year-old locksmith and welder, who only gave his first name, told AFP at a polling station in Chisinau.

Some 20 political parties and independent candidates were running for the 101 parliamentary seats.

'Massive interference'

After casting her vote, pro-EU President Maia Sandu of PAS warned of a "massive interference of Russia".

Moldova's cybersecurity service said Sunday it had detected several attempted attacks on the electoral infrastructure, which were "neutralised in real time... without affecting the availability or integrity of electoral services".

Election day was marked by a string of incidents, ranging from bomb threats at multiple polling stations abroad to voters photographing their ballots and some being illegally transported to polling stations. Police also detained three people suspected of plotting to cause unrest after the vote

In the breakaway region of Transnistria, authorities, in turn, accused Chisinau of "numerous and blatant" attempts to limit the vote of Moldovans living in the separatist territory by reducing the number of polling stations and other tactics.

The government has accused the Kremlin of spending hundreds of millions in "dirty money" to interfere in the campaign.

In the lead-up to the vote, prosecutors carried out hundreds of searches related to what the government said was "electoral corruption" and "destabilisation attempts", with dozens arrested.

(FRANCE 24 with AP)

The separatist region of Transnistria has long been the thorn in the side of Moldova's pursuit of European Union membership – a fact thrown into sharp relief as parliamentary elections loom.

Issued on: 26/09/2025 - RFI

By: Jan van der Made

At the 28 September elections in Moldova, most people in the breakaway region of Transnistria won’t vote.

"There are no polling stations. They consider themselves independent,” says Nico Lamminparras, an expert in the politics of Transnistria based in Helsinki.

Transnistrians who want to vote can do so, if they cross the artificial border formed by the Dniester river into Moldova proper, where the government will open several polling stations.

The inhabitants of Transnistria are predominantly pro-Russian and "local authorities continue to promote an Eastern [pro-Russian] orientation," Lamminparras told RFI.

The region held its own referendum in 2006, opting to “go back home, to Russia,” he added – a move that underlined the enclave's metaphorical, if not geographical, distance from Moldova and the European Union.

Moldova will keep pro-EU course despite Russian threat, Popescu tells RFI

It is unclear how many Transnistrians will turn out to vote later this month.

According to Chisinau-based Regional Trend Analytics, a socio-economic watchdog, during last year's presidential elections and referendum some 30 polling stations were opened but only a few people turned up because of false reports of mines and blocking of bridges.

Soviet era

Transnistria has historically been multi-ethnic, its population shaped by waves of migration during the Soviet era, with substantial Russian and Ukrainian communities.

Joseph Stalin’s annexation of Bessarabia from Romania in 1940 merged it with Russian-speaking Transnistria to form the Moldovan Soviet Socialist Republic.

Following the Soviet collapse, as Moldova drifted towards nationalism and a potential union with Romania, people in Transnistria, wary of losing Russian cultural ties, declared independence in 1990.

Armed conflict, resulting in some 1,000 dead, broke out in 1992, with the 14th Guards Combined Arms Army branch of the Russian Army intervening to support the separatists.

The resulting ceasefire cemented Transnistria’s de facto independence, although this is not recognised internationally and a “frozen conflict” persists to this day.

Moldova President warns European Parliament about Russia threat

Different model

Transnistria is not the only Moldovan region that wants to chart its own course.

Still under Moldovan control, southern Gagauzia offers a different model. The enclave is home to the Gagauz, a Turkic Orthodox Christian people.

It also declared independence in the early 1990s. But rather than secede, Gagauzia accepted autonomy within Moldova in 1995, obtaining constitutional guarantees and substantial cultural self-determination.

Russian remains the dominant language, and Gagauzia continues to harbour pro-Russian sentiments, occasionally threatening to secede if Moldova were to change its status of autonomy.

Yet unlike Transnistria, Gagauzia participates in Moldovan elections and retains economic links to the central government, making its autonomy more functional and less destabilising.

Macron pledges France's 'determined support' for Moldova joining EU

EU accession

The Transnistrian question casts a long shadow over Moldova’s EU accession process.

“The pro-Europeans will have a clear majority,” predicts Laminparras – albeit a declining one, meaning that "Moldovan policy will keep on as it is".

For Transnistria, he says, a possible Moldovan accession could prove disastrous.

"The EU process implies tariffs for the Transnistrian products passing the boundary,” which he added would deepen the economic gulf between the two banks of the Dniester.

Others, however, are more optimistic.

"It's clear that it's much better to join the European Union without a separatist conflict,” Nicu Popescu, Moldova's former deputy prime minister and foreign minister, who is running in the parliamentary elections on the list of the pro-European Action and Solidarity Party, told RFI. “The EU itself was founded on a divided state – West Germany."

According to Popescu, in the case of Moldova "the hope is that by joining the EU, reintegration of the country will in fact be made easier and more sustainable".

Moldovans are heading to the polls on Sunday – in what is widely seen as the most important election since the country gained independence – facing a political crossroads with implications for its European future, regional security and domestic stability.

Issued on: 28/09/2025 -

By:Jan van der MadeFollow

Advertising

At stake are all 101 seats in the unicameral parliament, which are elected via proportional representation.

The significance of Sunday's vote transcends national boundaries. Moldova’s next government will determine whether the country maintains its accelerated path toward European Union membership, or pivots back toward deeper ties with Moscow.

The election is set against a backdrop of Russia’s ongoing war in neighbouring Ukraine, and intense international interest in Moldova’s democratic resilience.

Russian disinformation and Moldova's media landscape

Who are the main contenders?

The pro-European Party of Action and Solidarity (PAS), led by President Maia Sandu, seeks to consolidate Moldova’s European trajectory. PAS entered this race as the incumbent majority, campaigning on promises of anti-corruption and EU integration.

Facing off against the PAS are two pro-Russian alliances – the Patriotic Electoral Bloc (BEP) and the Alternativa Bloc.

BEP consists of former presidents Igor Dodon and Vladimir Voronin. But in the period leading up to the elections, their forces were weakened after the Central Electoral Commission banned some of the participants.

On Friday the commission excluded the pro-Russian party Greater Moldova from the election citing suspected illegal financing and foreign funding. Authorities suspect the party tried to influence voters with money and may be linked to the previously banned party led by exiled businessman Ilan Shor.

Greater Moldova’s leader, Victoria Furtuna, described the decision as biased and intends to appeal.

Last week the commission banned another pro-Russian party, Heart of Moldova, part of the pro-Russian Patriotic bloc, from participating in the bloc, amid similar concerns.

The opposition forces advocate for Moldova’s neutrality and a sovereign course, warning that closer EU alignment would erode the country’s independence and social fabric.

The Alternativa Bloc, led by Chisinau mayor Ion Ceban, former Prosecutor General Alexandru Stoianoglo, former prime minister Ion Chicu and strategist Mark Tkaciuc, positions itself as a “neither West nor Russia” coalition.

Its pragmatism has drawn voters tired of ideological confrontation, although its image took a hit when Ceban was denied entry to Romania in July over security concerns – a ban which extends to the entire Schengen visa-free travel area, Romania's foreign ministry said.

Russian influence

Moscow’s campaign to prevent a pro-EU majority has been well documented, and multi-faceted.

Intelligence leaks and investigative reports such as those by the Bulgaria-based Disinformation observatory, reveal strategies ranging from funding pro-Russian parties, deploying social media disinformation, orchestrating protests and targeting the Moldovan diaspora with false narratives and cash inducements.

Last week, Moldovan authorities detained 74 individuals accused of involvement in a Moscow-driven plot to destabilise the elections.

French support, Russian meddling and the fight for Europe’s frontier in Moldova

For the EU, Moldova’s election is a litmus test for the bloc's ability to withstand Moscow’s interference campaigns, and anchor reform and stability at its eastern border.

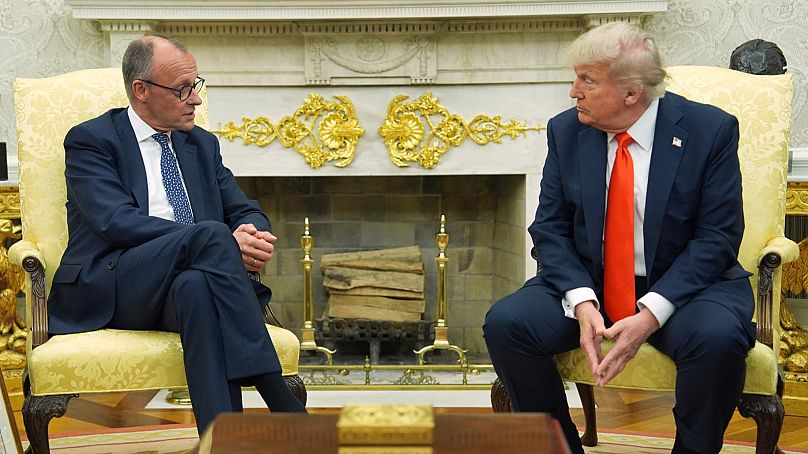

Brussels and several member state leaders have demonstrated support for Moldova’s sovereignty, with Emmanuel Macron, Friedrich Merz and Donald Tusk paying recent visits.

The EU has imposed targeted sanctions on individuals and groups suspected of fuelling Russian interference, while stepping up assistance for media pluralism, electoral transparency and civil society organisations.

After Moldova was nearly derailed from its EU accession path in last year’s presidential election, the authorities have taken controversial steps to prevent this happening again ahead of the September 28 general election.

In recent months, the Moldovan authorities have unveiled illegal financing schemes to support pro-Russian parties, and criminal organisations channelling money to buy votes and organise anti-government protests. They also exposed sophisticated online campaigns involving bot farms and influencers linked to Russia. The authorities in Chisinau responded actively, including with strategies that would, under normal circumstances, be considered on the verge of unconstitutional.

This began with the dissolution of the Șor Party led by fugitive oligarch Ilan Shor in June 2023 on grounds that were seen as flimsy at the time. Now, Shor’s role in the country’s elections is better documented. Sentenced in Moldova to 15 years of prison for financial fraud, he is openly organising and financing the pro-Russian opposition in Moldova, while also helping Russian authorities to bypass Western sanctions through cryptocurrency arrangements, as announced by the US Department of the Treasury’s Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) earlier this year.

On September 26, two opposition parties, including Inima Moldovei (Heart of Moldova) led by former governor of Gagauzia Irina Vlah, one of the three parties in the main opposition coalition, were banned from running in the election just two days before the vote.

Like former president Igor Dodon, Vlah has regularly met Russian President Vladimir Putin and argued for equal collaboration with both the EU and Russia. Her party had not yet been found guilty of illegal financing activities. However, the Central Electoral Commission (CEC) decided to suspend the party’s activity for 12 months on “reasonable suspicions” of illegal financing, at the request of the Ministry of Justice. The decision can be appealed, but its effects were enforced before the appeal, starting with the September 28 election.

The new party led by former prosecutor Victoria Furtună was also suspended for 12 months, allegedly for connections with Shor.

In another controversial previous move, the Moldovan authorities restricted the civil rights of opposition leaders, including Vlah, primarily by freezing their bank accounts. These measures were based not on court rulings but on sanctions imposed by Western countries for “active support of Russia”. The Constitutional Court allowed the intelligence services to impose such civil rights restrictions based solely on political sanctions set by foreign states.

Also on September 26, the CEC decided to relocate five voting stations initially designated for voters in Transnistria. Originally announced to be located within the separatist region, the stations were moved to territory controlled by the constitutional authorities only two days before the ballot.

Opposition parties claimed that construction works on bridges across the Dniester River, separating the two sides of the country, had been initiated by the authorities deliberately before the elections in order to prevent pro-Russian voters from reaching polling stations.

On election day, the authorities reported the organised transport of Transnistrians to polling stations across the Dniester as a breach of electoral procedures.

This year, the number of voting stations in Russia, home to a significant part of the Moldovan diaspora, has been severely restricted. Moldovans in areas far from Moscow were transported to Belarus to vote in Minsk, reportedly organised by Șor. Moldovan authorities also reported this operation as a violation of electoral regulations.

In another unusual move, President Maia Sandu became actively involved in supporting the Party of Action and Solidarity (PAS), which she founded, despite constitutional provisions.

With strong support from EU institutions, she campaigned for the country’s EU accession while criticising other pro-EU parties as covert Russian vehicles. A side effect of this strategy was the lack of political allies for the PAS, which will have to secure the majority of votes in order to remain in office. The authorities’ limited engagement with the Russian-speaking population during the EU accession process was evident and created space for pro-Russian propaganda.

Not only President Sandu, but also the public administration, has engaged in supporting the pro-EU parties.

In its first monitoring report on the September 28 parliamentary election, civil society organisation Promo-LEX stated that abuse of administrative resources is a “systemic phenomenon”, tolerated and still practised despite the existing legal framework.

“Without real sanctions, legislative clarifications, and a genuine delimitation between party and state, this type of abuse risks becoming normal,” warned Promo-LEX experts.

Conditions in Moldova have been far from normal since Russia invaded Ukraine, and especially in recent weeks.

This follows a turbulent period in Moldovan politics since Russia annexed Crimea in 2014. Shortly afterwards, it was revealed that pro-EU politicians were involved in the $1bn bank fraud scandal that bankrupted the country’s three largest banks, adding some 8% of GDP to public debt and complicating EU accession efforts.

The parliamentary election of November-December 2023 and the presidential election and EU accession referendum in September 2024 marked a gradual increase in activity by pro-Russian politicians operating in coordination with the Kremlin.

The pro-EU authorities in office since 2021, headed by Sandu, have been caught between economic pressures generated by the war in Ukraine and Russia’s energy leverage on one hand, and resistance to reform from the judiciary on the other. The latter has prevented firm prosecution of corruption, including what Sandu has described as electoral corruption.

Moldova’s proactive response must be viewed in the context of the hybrid war waged by Russia in cooperation with a significant part of the local population. Court rulings should be based on the evidence available at the time, but the complexity of digital tools poses serious challenges in addressing electoral criminality.

The elections in Moldova, carried out under hybrid attacks from the Russian Federation, illustrate the need for a revised set of best electoral practices in light of new financial, media and communication instruments. Ballot reruns, as seen in Romania, or reactive policies may provide short-term fixes, but they remain debatable and insufficient for ensuring genuine elections in which the rights of all candidates are respected.

Telegram owner Durov says French, Moldovan governments asked him to block anti-government accounts ahead of elections

.jpeg)

The owner of the Telegram messaging service Pavel Durov said that the French intelligence approached him earlier this year and asked him to block anti-government channels in the run up to this weekend's elections on two occasions in a post on Telegram on September 27.

“About a year ago, while I was stuck in Paris, the French intelligence services reached out to me through an intermediary, asking me to help the Moldovan government censor certain Telegram channels ahead of the presidential elections in Moldova,” Durov said.

Tech billionaire Elon Musk reposted the message with the brief comment: “Wow.”

The founder of Telegram encrypted messenger service now lives in self-imposed exile and was arrested in August last year as he got off his private jet in France.

Durov holds a dual French citizenship since 2021 was held for several days on child pornography and other cybersecurity charges by the French authorities. The officials said that Durov has failed to monitor his service which is widely used by criminals to conduct business including selling illicit pornography, although the charges were later dropped.

“After reviewing the channels flagged by French (and Moldovan) authorities, we identified a few that clearly violated our rules and removed them. The intermediary then informed me that, in exchange for this cooperation, French intelligence would “say good things” about me to the judge who had ordered my arrest in August last year,” Durov said in his post.

“This was unacceptable on several levels. If the agency did in fact approach the judge — it constituted an attempt to interfere in the judicial process. If it did not, and merely claimed to have done so, then it was exploiting my legal situation in France to influence political developments in Eastern Europe — a pattern we have also observed in Romania,” Durov added.

Telegram is one of the favourite messaging services and has played a key role in Belarus’ mass anti-government protests in 2020 and has been a thorn in the side of the Russian authorities, who tried to ban th service in 2008, but failed.

This weekend's elections are proving controversial and have led to accusations of an attempt to manipulate the outcome for the pro-Europe Sandu). The authorities banned two of the main opposition parties only 48 hours before the vote. Voting in the breakaway Moldovan region of Transnistria, which is under Russian occupation, has been cancelled. No polling stations have been provided for Moldovans living in Russia, according to reports, while extra stations for Moldovans living in the EU have been provided.

Durov said he was approached a second time by the French intelligence service with a more explicit politically motivated request to close down anti-government channels, which he refused to do.

“Shortly thereafter, the Telegram team received a second list of so-called “problematic” Moldovan channels. Unlike the first, nearly all of these channels were legitimate and fully compliant with our rules. Their only commonality was that they voiced political positions disliked by the French and Moldovan governments,” Durov wrote. “We refused to act on this request.”

Durov has taken a radical non-interference stance and says that it will not censor the content on its service and flatly refuses to cooperate with governments. However, after his arrest in France, investigations have found that he has on occasion cooperated with the Federal Security Service (FSB), the Russian security service.

“Telegram is committed to freedom of speech and will not remove content for political reasons. I will continue to expose every attempt to pressure Telegram into censoring our platform. Stay tuned,” Durov posted.