First published at Polity.

The National People’s Power (NPP) has made history. With its unprecedented, record-breaking electoral victory at the general election of 2024, the NPP has succeeded in engineering popular dissent towards comprehensive regime change. Its parliamentary super majority has been secured on the back of a near complete rout of the political establishment, while seemingly transcending the ethnic majoritarianism manifested by governments in the past to obtain electoral victories. Most significantly, the NPP’s winning coalition is the largest and most diverse ever assembled, consisting of workers, farmers, fishers, women, minoritised communities, and the urban poor all across the country. How, then, can the NPP’s victory and mandate be understood; and what will the next five years look like?

An unprecedented victory

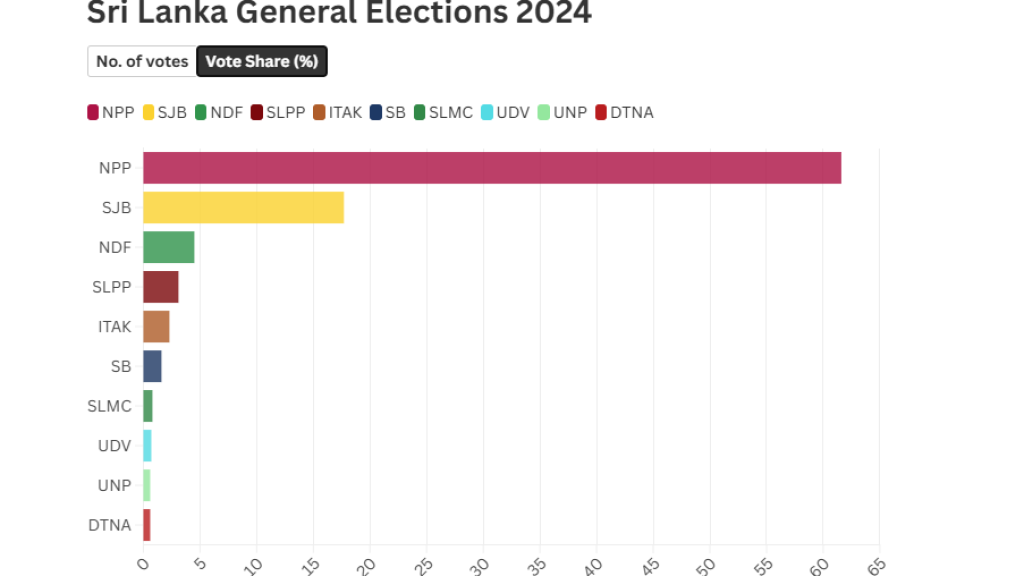

The scale of the NPP’s victory is massive. It is the first party to win a two-thirds parliamentary majority in the proportional representation era, without an electoral alliance. Its vote share increased from 42.3% in the presidential election to 61.56% in the general election, translating to 159 seats, well past the much vaunted two-thirds required for constitutional amendments to be passed. This was facilitated somewhat by the drop in voter turnout (from 79.46% to 68.93%), but that it has managed to achieve this under an electoral system which moderates electoral blowouts, is genuinely remarkable.

Despite the decrease in turnout, the NPP retained all 5.7 million voters from the presidential election and won over 1.2 million voters more. It doubled down on its winning coalition in the presidential election of the suburban middle class and rural poor, while making new inroads with the urban poor. Electoral districts where these constituencies are decisive, such as Ratnapura, Monaragala, and Kandy, respectively, were more divided previously but have now levelled with the party’s high national average. The NPP now has elected MPs from every single electoral district.

Significantly, many of its new voters come from Tamil-speaking communities across the country. In the seven electoral districts across the North, East, and Malaiyaham, the NPP vote share increased by an average of 103% compared to 44% across all 15 ‘Southern’ electoral districts, indicating the NPP’s rapid conversion of considerable numbers of Tamil-speaking voters in the short 54-day span between elections. Election night was full of highly symbolic and emotive NPP victories, such as in the polling divisions of Jaffna, Maskeliya, and Colombo Central, representing previously unthought-of wins for a Sinhala-based party across the country’s minoritised ethnic communities. In terms of its totalising cross-ethnic and cross-class composition, the NPP’s victory is only comparable to Chandrika Bandaranaike Kumaratunga’s presidential election victory in 1994. Unlike then, however, the NPP now wields both the presidency and a two-thirds parliamentary majority.

The upended political landscape

The NPP’s primary appeal to the electorate was to clear out the old establishment. The electorate responded resoundingly, voting out extraordinary numbers of decade-long mainstays in the parliament, adding to the many who chose to bow out pre-election. Voters have especially responded to the manner of the NPP’s appeal, refusing to make electoral deals with other political parties or personalities and thus forgoing the bedrock of electoral campaigning in Sri Lanka. In contrast, voters would have seen other mainstream parties making deals with local power brokers in the same way as they have done for decades. The culture of patronage and clientelism that developed around elections on the island, particularly codified by J. R. Jayewardene’s constitutional albatross, had seemed inexorable until now. Wickremesinghe’s government was an almost farcical distillation of this culture — composed of perpetually side-switching MPs, many with credible allegations of corruption and criminality, led by an unelected president — and has now been voted out almost entirely.

With the result, the NPP has precipitated a complete implosion of the centre-right to the right-wing of Sri Lankan politics. This includes a clear and comprehensive rejection of Ranil Wickremesinghe whose electoral vehicle, the New Democratic Front, garnered only 4.49% and 500,000-odd votes, a sharp drop from his 17.27% and 2.3 million votes at the presidential election. Wickremesinghe’s powerful backers across the political, business, media, and civil society establishment, sold the idea of him supernaturally providing economic ‘stability’ to the country following the economic collapse of early 2022. This was evidently worth the price of his many infractions, such as actively scuttling the local government elections scheduled for early 2023, passing a dizzying raft of repressive laws, and actively infringing on citizens’ fundamental rights, particularly on assembly and expression. In his latest incarnation, Wickremesinghe threw his mask off completely, eschewing the liberal, cosmopolitan persona he had cultivated for decades to settle into the autocratic, right-wing politician he was moulded into in the hands of his uncle nearly 50 years ago — which now, the electorate has decisively rejected.

It also includes a decisive rejection of the Samagi Jana Balawegaya (SJB), a party formed as a personality vehicle against Wickremesinghe, whose primary appeal to the electorate was a promise to be the United National Party (UNP) but cleaner — Ranil without Ranil. The SJB went from 32.76% at the presidential election to 17.66%, shedding more than half or nearly 2.4 million of its 4.4 million voters. Any designs its leader Sajith Premadasa had to mould a politics closer to the superficially welfarist politics of his father were ostensibly undermined by the ardent neoliberals in the SJB camp, such as Eran Wickramaratne and Harsha de Silva. This left the SJB’s proposition to the electorate largely indistinguishable from Wickremesinghe’s, save for the faces. While these results could perhaps provide space for a combined re-organisation of the right wing, such a project must also contend with the electorally reviled personalities of Premadasa and Wickremesinghe.

The NPP may also have sealed an endpoint to Rajapaksaism. The Podujana Peramuna (SLPP), running on a glutinous platform of Sinhala ethnonationalism, effectively maintained the same 350,000 voters across the presidential and parliamentary elections. The three MPs elected to parliament is a comically neat reversal of fate between it and the NPP from five years ago. It was unable to make any headway despite the misfortunes of the right and the NPP’s ostensible move in a progressive direction. It is telling that in all the narratives from the election, the collapse of the SLPP does not figure as a main story. But its complete rout in its Southern Province heartlands, middle-class strongholds in suburban Colombo, Gampaha, and Kurunegala, and estuaries across the North Central and Sabaragamuwa provinces, after its heady highs just five years ago, is devastating.

The last reckoning the NPP’s victory has presented is for the political parties claiming to represent Tamil-speaking communities which Tamil-speaking voters — Ilankai Tamil, Muslim, and Malaiyaha Tamil — have abandoned in significant numbers. In the North and East, perceived infighting between and within Tamil parties, headlined by the acrimonious disintegration of the Tamil National Alliance (TNA), along with a raft of new independent groups, saw pronounced splintering of Tamil votes. Contesting separately, the TNA’s former constituents, the Ilankai Tamil Arasu Kachchi and Democratic Tamil National Alliance, dropped one seat to nine and the Tamil National People’s Front dropped a seat to just one, indicating perhaps that the electoral salience of Tamil nationalism has softened this time around. Long time government fixtures such as the Eelam People’s Democratic Party and Tamil Makkal Viduthalai Pulikal were also defenestrated outright. Fortunes of Muslim and Malaiyaha Tamil political parties — such as the SJB-aligned All Ceylon Makkal Congress, Sri Lanka Muslim Congress, Tamil Progressive Alliance, and the Wickremesinghe-aligned Ceylon Workers’ Congress — also largely stagnated.

All this represents a significant reconfiguration of ethnic politics in the country. Many Tamil-speaking, especially young, voters have seemingly thought of the parties claiming to represent them in similar ways to what Sinhala voters thought of the establishment parties they were ousting. There is now a cadre of at least 18 Tamil-speaking MPs across the country elected under the NPP banner. The party in government does not have to rely on other, particularised parties for the illusion of minority representation and accommodation. Whether this makes a material difference or not is now entirely up to the NPP.

In sum, the NPP’s victory provides an electoral closure of sorts to the Aragalaya, which the NPP managed to capitalise on fully while making only careful, implied reference to it. Conversely, the newly formed People’s Struggle Alliance led by the Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna (JVP)-breakaway Frontline Socialist Party, which campaigned explicitly on the Aragalaya, failed to win a seat. The Aragalaya’s propulsive call for system change was a demand for an entirely new social contract. The NPP has already achieved this thus far by decimating the political establishment, almost completely achieving its call to cleanse the Diyawanna. The harder task is what lies beyond.

A mandate for left policies

In policy terms, the NPP’s mandate has explicit and implied meanings which require careful deciphering. Pre-poll surveys indicated numerous overriding concerns stemming from the economic crisis, including the spiralling cost of living, unemployment, and precipitous investment in education, healthcare and agriculture. The NPP’s winning majority includes farmers, fishers, workers, urban poor, and the indebted, who bore the brunt of both the economic crisis and the austerity policies supposedly mitigating it that Wickremesinghe’s government forced through.

While the NPP did not openly campaign on a left platform, often shying away from associating with the JVP’s socialism of the past, the people as a whole have subscribed to its explicit promises of dignified livelihoods with better wages and security, improved public provision of health care, education, transport, social security and freedom from indebtedness. Embedded in this was also a promise to remake the national economy in ways empowering farmers, fishers, and local manufacturers.

The NPP’s victory can also be interpreted as a definite mandate against the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and World Bank-dictated austerity, labour reforms, and other structural reforms that clearly favour corporate and business interests over working people. The political leadership and élites alike who have been accomplices in the élite-corporate capture of the state over the last two years have been decisively, if temporarily, defeated. Their mouthpieces will nonetheless attempt to argue otherwise, that the NPP’s win is not a rejection of austerity or the neoliberal reforms Wickremesinghe rammed through over the past two years. But the grounds to make this claim are feeble, when the two parties who campaigned on continuing the current economic settings to the letter could barely muster 20% of the vote combined.

The coming policy prospects

Will the NPP government actually carry out such a mandate? And what would the future be like? Will it be a repetition of the Yahapalanaya regime’s politics which paved the way for a deluge of Sinhala ethnonationalism in 2019? A prognosis of the NPP government’s future on policy terms is necessary to discern this.

The IMF programme’s future

The 17th IMF programme is the noose that hangs around the NPP government’s neck. What the new government does with this noose will determine the future, not only of the NPP, but of Sri Lankans themselves. In its election manifesto and various political enunciations, the NPP maintained that they would renegotiate the IMF programme and propose a new Debt Sustainability Analysis (DSA). Having sleepwalked into a debt restructuring deal with bondholders that Wickremesinghe agreed to in principle just two days ahead of the presidential election, the NPP government is already in a tight position without much space to manoeuvre the dispensation of debt payments in the coming years. The fiscal and monetary authority of the new government is also fettered due to the new Central Bank and Public Debt Management Acts that Wickremesinghe steamrollered under IMF supervision. Having not articulated prospects outside the IMF agreement, the NPP government is also likely to generate hostility from those who believe that ‘There Is No Alternative’ but the IMF, particularly among its new middle-class electorate.

How likely is the IMF programme to be renegotiated, and to do what? The IMF programme — with its conditionalities on government expenditure, subsidies, tax revenue, public services, state-owned-enterprises, and social security provisions — is a straitjacket which restricts the government’s ability to innovate, industrialise, and invest in productive sectors of the economy while providing public services and social security. Renegotiating an IMF programme does not mean a simple bargain of tax rates and salary hikes. It means removing the straitjacket to liberate the state’s capacity to undertake structural reforms vital to empower working people, rectify the terms of trade, innovate and industrialise the economy, to exit the vicious cycle of dependency and economic crises that have been permanent features in the Sri Lankan economy.

Renegotiating the IMF programme involves coming to terms with the fact that the IMF facilitated debt restructuring process with both bilateral creditors and bondholders failed to reduce Sri Lanka’s external debt stock to a sustainable level. The restructuring process based on a faulty DSA was concluded on terms highly favourable to the creditors, with the threat of a second default looming large in the intermediate period. In contrast, the exclusive subjection of the EPF to domestic debt restructuring under the IMF’s watch has radically diminished working people’s social security. The IMF programme so far has only meant that Sri Lanka can borrow from private capital markets at high interest rates to correct any shortfall in foreign exchange needed for debt servicing. Instead of liberating the productive capacities of the Sri Lankan economy, the IMF programme has imposed its financial hegemony on Sri Lanka.

Another feature of the IMF programme is what Sri Lanka owes to the IMF. Debt is the key to IMF’s meddling. The Extended Fund Facility (EFF) of USD 3 billion for 48 months, approved in March 2023 and disbursed in eight tranches, must be repaid in 4.5 to 10 years. As a result of surcharges, Sri Lanka has to repay IMF debt at 8.36% interest rate after 2026. Likewise, the IMF’s EFF is worse than dollar denominated bonds that Sri Lanka floated and defaulted on in 2022.

Renegotiating the IMF programme is like wrestling with a giant octopus and its multiple arms. The most immediate challenge comes with the Budget due in February 2025. The IMF’s ‘wait and see’ stance regarding the third tranche of the EFF is a blatant act of meddlesome policing to ensure that the new government’s economic policy bends to its conditions. Without substantial debt reduction or consideration of debt to foreign exchange revenue ratio when assessing Sri Lanka’s debt-carrying capacity, debt servicing will exert pressure on foreign exchange revenue after 2027. If the Sri Lankan economy grows, debt servicing on bonds could exceed USD 1 billion by 2028. The dividends of the economic growth that the NPP government will engineer would be reaped by private creditors like Blackrock, HSBC, and Ashmore Group, not the people. A fight between the NPP government and the IMF to steer economic policy can only mean a collision and an exit.

The NPP government thus needs a much better-articulated stance vis-à-vis the IMF. The first would be to build up leverage. Even if the debt restructuring deal was concluded by Wickremesinghe, the NPP government should conduct an odious debt audit to determine the legitimacy of the debt incurred by the Rajapaksa-Wickremesinghe governments. It should also formulate a new DSA to expose the erroneous DSA framed by the IMF. The NPP government should create a supportive ecosystem of debt experts, local and international, who can work with the government to tackle the IMF and creditors. Finally, the NPP government also needs to build a domestic consensus. The NPP government is yet to explain to the public why it inked an injurious bond deal with private creditors in early October. Secrecy and announcements by deadlines, like Wickremesinghe did, will only benefit hostile parties. If the government decides to forgo all such independent action and capitulate to the IMF’s wishes, it will be unable to actualise its mandate and the anti-austerity development aspirations of the people, sealing its own fate.

Foreign relations

The IMF programme’s fate is intimately tied to Sri Lanka’s precarious international position. Enacting the people’s mandate demands conducive diplomatic relations to secure productive investments and development aid, and to act as an external buffer to fend off the pressure of creditors, the interference of International Financial Institutions (IFIs), and the hostility of powerful countries in the Global North. The adverse travel advisory issued by the United States recently over supposed terrorist activity in Arugam Bay is a case in point illustrating Sri Lanka’s external fragility. Revamping Sri Lanka’s foreign relations to accord with the people’s mandate also requires a rejection of the neoliberal geopolitics that the previous regimes upheld. The promotion of Sri Lanka as a destination of cheap labour, cheap resources, and a satellite of the Global North, has proliferated precarious jobs, footloose and extractive investments, capital flight and geopolitical vulnerability.

Building back Sri Lanka’s foreign relations needs a comprehensive rethinking of the what and how of external engagements. How Sri Lanka re-aligns with India and China in this regard will be crucial. Over the past years, Sri Lanka has become a destination for exporting surplus Indian and Chinese capital, surplus production and, at times, surplus labour, amounting to the dispossession and displacement of people, ecological destruction, harm to local farmers and producers, and rising xenophobic politics. India’s engagement in Sri Lanka in the aftermath of the default has been to push Sri Lanka towards the US and IMF to balance China. Moving forward with a people-centric foreign policy requires transcending the traditional balance to actually address the development aspirations of Sri Lankans while ensuring national autonomy.

In this regard, cultivating closer diplomatic relations with many other nations is vital — including with Southeast Asian nations to resurrect the manufacturing sector in Sri Lanka; and with African and Latin American countries to join collective action on the new debt crisis affecting the Global South and to resist the financial hegemony of IFIs and private creditors. The reconfiguration of Southern relations around BRICS+ is also an attempt to take down the structural power of the Global North, which perpetuates debt and dependency in the Global South. The Third World is increasingly advocating for a third way and Sri Lanka should proactively engage in these processes by taking a leadership role as it did during the heydays of the Non-Aligned Movement. Such Southern alliances will bear fruit if Sri Lanka descends again to vulnerable financial terrain in 2027-28 over external debt servicing.

Constitutional reforms and the national question

The NPP’s surprise two-thirds parliamentary majority means that expectations will now be increased on delivering a raft of constitutional changes it could have paid lip service to otherwise. Foremost amongst these will be the abolition of the executive presidency, which it has long advocated for. Whether that comes in the form of a constitutional amendment (and public referendum) or a new constitution altogether is entirely up to the NPP. While the NPP has promised a new constitution, it would be wary of a Yahapalanaya-type constitutional reform exercise which, despite great promise (particularly through its public consultations, which included incumbent prime minister Harini Amarasuriya in another life, and an expanded suite of social and economic rights), amounted to little more than a cynical sop thrown by Wickremesinghe to the TNA and civil society. Whatever path it chooses, however, the NPP will face little parliamentary resistance, and it thus has the unprecedented opportunity to remake the entire Sri Lankan state structure if it wishes, in its image or otherwise.

The NPP government will also be expected to deal with Sri Lanka’s raft of repressive statutes, amongst them the Prevention of Terrorism Act (PTA) and the Online Safety Act. The government has already cornered itself into repealing the PTA, following the backlash to its deployment over the Arugam Bay episode. Such pressure coming from citizen groups and communities affected by such state repression has proven to be far more effective than from Colombo-based civil society organisations, which have thoroughly discredited themselves with their virtual silence over the Wickremesinghe government’s multitudinous repression, and whose advocacy often amounts to unsightly moral equivocation (such as for instance, replacing the PTA). Expectations will also be high for a series of other social reforms, including education curriculum reforms, policies for people with disabilities, a rejuvenation of arts and culture industries, anti-discrimination measures and the decriminalisation of same-sex relations. Such expectations are especially high because many leading advocates of these reforms are now NPP MPs.

On the national question, the NPP faces thornier ground. The NPP has achieved its victory while running two non-racist election campaigns, and this is significant, even if the bar is subterranean for Sinhala political parties. Its preferred position on ethnic relations has been to present a front of ethnic harmony, promising not to antagonise minoritised communities but not promising much substantively beyond this to address their specific grievances. This positioning, however, is entirely complicated by the JVP’s past, particularly its vociferous opposition to Tamil self-determination in the 1980s, and its chauvinist cheerleading for the “military solution” to the war from the early 2000s. The NPP government has already reiterated the Wickremesinghe government’s opposition to the current UN Human Rights Council resolution on Sri Lanka, which calls for the continued collection of evidence to be used in war crimes proceedings. It has also maintained an insistence on domestic mechanisms to address the UNHRC Resolution, though it is unclear yet if it intends to continue Wickremesinghe’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission, reheat the Yahapalanaya era’s impotent transitional justice mechanisms — both resoundingly rejected by survivor communities — or create something new.

There is compelling moral space for the NPP in particular to act on issues of accountability, given the atrocities the JVP itself has suffered in the past over its two insurrections. But it has presented no such programme to the electorate and will find it far easier to argue that voters in the North and East voted on economic relief and anti-corruption. This argument is credible to some extent, given that the Tamil political parties advocating stronger accountability measures failed to make any headway. In contrast to the question of accountability, the NPP has found it easier to make overt, if indeterminate, promises on returning state-occupied lands to Tamil civilians, ceasing colonisation programmes in the North and East, and releasing political prisoners.

It is up to the NPP to craft a substantive response to the national question, beyond both the outright violent antagonism and the facetious liberal responses of governments in the past. If the NPP is to take succour from its endorsement by Tamil-speaking communities, as it has indeed publicly been doing, then those voters may themselves be right to expect more than an inept, liberal ලොවේ සැමා (‘together as one’) response. It remains the case that in Sri Lanka’s majoritarian state, the terms of democratic engagement for Tamil-speaking communities are markedly different to the Sinhala community. For many Tamil-speaking voters, voting is often invariably about survival rather than political aspiration. The NPP can decide whether this pattern persists.

Into the unknown

The scale of the NPP’s victory also means that the consequences of its potential failure are profound. While the NPP makes no aspiration to socialism, and has seized power in perhaps exceptional circumstances, its downfall would be a setback to progressive politics by generations. Such a downfall will come entirely if it fails to deliver on its mandate of providing substantive socioeconomic relief, protection, and sovereignty, whether that is deemed a left mandate or not.

Waiting in the wings to snatch power back are all shades of the political establishment the NPP may have temporarily defeated, including the neoliberal right wing (through amalgamations of the Ranilist and SJB camps), the Sinhala nationalist wing (including a regenerated SLPP), or unsavoury reconfigurations of the two, such as Champika Ranawaka and Dilith Jayaweera. All these are largely reactionary, socially regressive political elements who will be smarting from their comprehensive political defeats, and therefore raring for vengeance. Such impulse, and their ability to return, should not be underestimated, especially in an era of permanent crisis both locally and elsewhere where comprehensive electoral victories have proven to be deeply fragile. Just as the voters have rewarded the NPP for implicitly taking up the Aragalaya’s mantle, the NPP would do well to remember that Sri Lankans are now self-possessed of the knowledge that they can oust governments from the streets as well as the ballot.

Against the faltering and decaying West, which is giving way both reluctantly and happily to various neo-fascist manifestations, the NPP’s assumption of power in Sri Lanka presents a possible resistant counterforce and a bulwark against the financialised, imperialist governance that spells mass violence and ecological dispossession for so many. From the small vantage of Sri Lanka itself, it could be a rallying force for a considered, people-centric politics that reasserts Third World sovereignty and autonomy. With its extraordinary electoral victory, the NPP has unprecedented power to address these questions. We now await the answers.

Pasan Jayasinghe is a PhD candidate in political science at University College London. Amali Wedagedara (PhD, Hawai‘i) is a feminist political economist and a senior researcher at the Bandaranaike Centre for International Studies (BCIS).

The Sri Lankan left’s long road to power

Devaka Gunawardena & Ahilan Kadirgamar

First published at Rosa-Luxemburg-Stiftung.

The victory of the National People’s Power (NPP) candidate, Anura Kumara Dissanayake, in the Sri Lankan presidential election represented a major shift in the South Asian state’s political trajectory. Dissanayake’s upset was soon followed by parliamentary elections in which his coalition won two thirds of the seats, an unprecedented feat since the system of proportional representation was established in the late 1980s. For the first time since the 1970s, a left-wing party is not only participating in a government coalition, but leading it. This uncharted political territory represents a great opportunity to put Sri Lanka on a more sustainable, egalitarian developmental path, but also poses great risks. The NPP could buckle under institutional inertia and international pressure, and fail to deliver the kind of change for which it was elected. Consequently, the stakes are high for the broader Left movement in this historic moment.

The recent political earthquake comes after two years under President Ranil Wickremesinghe, whom the establishment, ranging from mainstream media and think tanks to foreign lenders, credited with bringing “stability” to the island nation. Following years of gross mismanagement and incompetence on the part of previous President Gotabaya Rajapaksa, Sri Lanka defaulted on its foreign loans for the first time in April 2022. The ensuing economic crisis led to long queues for fuel and basic items, and soon provoked tremendous popular protests culminating in the aragalaya revolt that ousted Rajapaksa in July 2022. Yet, after the uprising died down, a subsequent government led by Wickremesinghe suppressed dissent and carried on with an International Monetary Fund-led programme of brutal austerity measures. Meanwhile, the people bided their time until the next election.

It was in this tense atmosphere that the left-leaning NPP was able to win such a decisive majority, assuming office amidst great hopes and expectations. The NPP is primarily the vehicle of its chief constituent party, the Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna (JVP). As the leader of both the JVP and the NPP, Dissanayake has portrayed the latter as a third force. He counterposes it to the corruption of the political class and its favoured home in Sri Lanka’s two historic parties, the Sri Lanka Freedom Party (SLFP) and the United National Party (UNP), along with their contemporary offshoots, the Sri Lanka Podujana Peramuna (SLPP) and the Samagi Jana Balavegaya (SJB).

That said, we should not forget that the JVP’s move to form the NPP in 2019 was in part intended to deflect attention from its own bloody history, including its first armed insurrection in 1971 and an even more brutal attempt in the late 1980s. At the same time, the NPP’s victory aligns with global trends, as ever-larger groups of voters swing between left- and right- populist alternatives to the political establishment from one election to the next.

The NPP shares many of the ambivalent characteristics of left-wing formations in other countries in which neoliberalism has become politically dominant. Yet unlike the main left-wing parties in India, for example, which have governed in states such as Kerala and West Bengal for decades, the NPP is assuming power at a time when the political and economic order is already fraying. Nevertheless, despite the severity of the economic hardship and the ferocity of the 2022 revolt, it remains uncertain whether Sri Lanka’s new government will be willing to take steps towards an independent development path. That would require a break with neoliberalism.

Since coming to power, the NPP has pledged to follow the terms of the previous government’s IMF Agreement. It even accepted an Agreement in Principle with external bondholders, which contains unprecedented legal revisions to allow a restructuring of Sri Lanka’s bonds largely to the benefit of commercial creditors. In this regard, it does not appear that the NPP is yet willing or able to resist the blackmail of global capital.

Nevertheless, the NPP cannot be dismissed outright, particularly given the widespread anger with austerity that facilitated the coalition’s victory. The JVP in particular has played a key, albeit contradictory role in the multifaceted history of the Sri Lankan Left. The party, and by extension its electoral coalition, has tended to reflect broader contradictions in the polity. It straddles various class fractions and social groups. The NPP now stands at a critical juncture. Will it address the grievances of an increasingly immiserated middle class and the working people, who have borne the brunt of the current crisis, by pursuing self-sufficiency with a strong redistributive dimension? Or will it fall back on aspirational rhetoric that appeals to its newer backers in the professional and business communities, while sticking to the current economic trajectory?

Critical engagement with the party’s history is necessary to explore if and how the NPP can be pushed to the left — a question that left-wing forces around the world must also ask themselves as they strive to build viable progressive coalitions amidst the unravelling of the world order.

Maoism, militancy, and cross-class coalitions

To analyse how the JVP came to be what it is today, we must situate it within the historical context of Sri Lanka’s Left. The country’s first official political party was the socialist Lanka Sama Samaja Party (LSSP), formed in 1935 before independence from Britain in 1948. The LSSP’s founding leaders were influenced by figures such as British economist and later Labour Party leader Harold Laski during their studies abroad. Yet the LSSP was not only Sri Lanka’s first party, but also the first Marxist party with an explicitly Trotskyist orientation. As political scientist Calvin Woodward put it, in Sri Lanka, Trotskyists (ironically) represented the orthodoxy, while the Stalinists were the renegades. The Communist Party (CP), which emerged as an offshoot of the LSSP, eventually gravitated towards an alliance with its former party, despite their ideological differences. Meanwhile, the Sri Lankan bourgeoisie found its political home in two mainstream parties, the UNP and its breakaway, the SLFP.

The “Old Left”, represented by the LSSP and the CP, grappled with the strategic dilemma of retaining political independence versus participating in coalitions with the left-leaning but nevertheless bourgeois SLFP. The latter won the elections of 1956, ushering Sri Lanka onto a path of state-led development and import substitution policies in conjunction with a nationalist mobilization focused on the Sinhala Buddhist majority. By the 1960s, however, a split formed in the CP. It led to the formation of the Communist Party – Peking Wing led by Nagalingam Shanmugathasan. Soon thereafter, Rohana Wijeweera emerged as the leader of a youth faction that went on to found the JVP.

Unlike the Old Left, the JVP and the broader “New Left” took a very different approach to the question of armed struggle. The JVP drew from a contradictory mix of ideologies, but was chiefly influenced by Maoism. While the Old Left “preached war and practiced peace”, to paraphrase its eminent theorist Hector Abhayavardhana, the JVP took the question of revolution seriously, even attempting an insurrection against the state in 1971.

The JVP’s break with the Old Left was not only based on a strategic disagreement, however. Rather, it crystallized around tensions specific to Sri Lankan society, especially in the rural South. The JVP embodied different social, linguistic, and generational cleavages within the Sri Lankan polity. Namely, it drew support from youth who primarily spoke Sinhala and tended to come from rural areas, as opposed to the leadership of the Old Left, which had an Anglophone character and cosmopolitan outlook. Meanwhile, the Old Left joined the United Front government (1970–1977) led by the SLFP, in which the LSSP remained a junior partner until 1975. The Old Left rationalized the government’s brutal response to the JVP insurrection, during which roughly 10,000 people were killed.

Dissidents within the Old Left such as Edmund Samarakkody, however, understood the JVP’s popular appeal. Although its ideology was contradictory, it had emerged as a response to the unresolved problems of underemployed youth in both rural and urban areas. Many in the younger generation had been unable to realize their aspirations even under the social-democratic regime of the post-1956 period. In this sense, the party’s base was among underemployed youth who sought employment in the state, but it also appealed to constituencies such as smallholder farmers, who felt that their needs were not being met by left-leaning governments focused more on their urban trade unionist supporters. This cross-class nature would prove to be both a strength and source of the JVP’s fundamental contradictions.

The left in decline

Meanwhile, the social-democratic coalition that governed Sri Lanka in the immediate post-colonial decades failed to pursue vigorous land redistribution. That oversight resulted in further impediments to rural mobilization and the broader transformation and development of Sri Lanka’s economy in a direction more capable of sustaining incipient efforts in self-sufficiency. The final nail in the coffin was the global economic crisis of the 1970s, which exposed the weaknesses of Sri Lanka’s model. The West precipitated this crisis through a capital strike, withdrawing its investments in the country and throttling its already-dependent economy.

Indeed, as Sri Lanka’s terms of trade began to deteriorate, the West began squeezing the country by denying foreign investment. It was a punishing response to the change of regime in 1956 and the country’s turn towards the Bandung project and the Non-Aligned Movement. After the election of the United Front government, the West curtailed even multilateral forms of engagement through institutions such as the IMF and World Bank.

On the domestic front, the government’s bloody crackdown fomented divisions within the Left and encouraged key figures and organizations to focus on the question of civil and democratic rights. Meanwhile, within the JVP, members disgruntled with the party’s lack of attention to the national question began to criticize its position on ethnic minorities. This was especially necessary given the JVP’s xenophobic attitude towards the Tamil minority in the Hill Country. In contrast to the Tamil community in the North and East, the Hill Country Tamils were brought over from India starting in the mid-nineteenth century to work as indentured labour on the plantations. The JVP accused them of being a “Fifth Column” for alleged Indian imperialism in the postcolonial era.

Yet such debates and revisions of the JVP’s judgments would only last through a brief period of rehabilitation during the late 1970s and early 1980s. Afterwards, the party went back underground and silenced the critical voices.

Between neoliberals and nationalists

The catalyst for this underground turn was the consolidation of an authoritarian right-wing government led by JR Jayewardene. Following the resounding victory of the United National Party in 1977, Jayewardene announced “open economy” reforms. The shift represented a break with the social-democratic regime and committed Sri Lanka to a path of economic liberalization. Shortly afterwards, the North and East plunged into civil war after devastating anti-Tamil riots in 1983 facilitated by Jayewardene’s government.

Proscribed by the government after the riots, the JVP engaged in a second and more brutal insurrection in the South in the late 1980s. Its ostensible reason was opposition to Indian intervention and the imposition of a quasi-federal solution to Sri Lanka’s national question. After its leadership was decapitated during a brutal counterinsurgency campaign by the state in 1989, it resurfaced and entered the political mainstream as a parliamentary party in 1994. Yet it continued to support the Sinhala Buddhist nationalist project. Believing that “the nation” constituted the last bastion of defence against imperialism, the party adopted harsh nationalist rhetoric and built alliances with far-right forces. Essentially, the JVP’s logic was that it had to prioritize protecting Sri Lanka from Western intervention on issues such as wartime human rights abuses before class issues could be engaged.

Eventually, the party became a supporter of Mahinda Rajapaksa, patriarch of the contemporary Rajapaksa dynasty, who won the Presidency in 2005. Rajapaksa engaged in unrestrained warfare to defeat the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE), which by then had ruthlessly eliminated their fraternal rivals. His ultimate victory in 2009 came at the cost of tens of thousands of Tamil lives.

Immediately after the war, however, the JVP rediscovered its role as a critic of the government, and became a relatively consistent proponent of democratic rights in parliament throughout the years leading up 2022. Yet it also faced a series of splits. A left-wing split, the Frontline Socialist Party (FSP), promoted struggles in the streets, while the JVP continued to prioritize parliamentary politics. At the same time, the JVP’s own bases of support shifted. The party attracted growing sections of the middle class, including urban professionals, who appreciated a “clean” alternative to the supposedly endemic corruption of Sri Lanka’s political class.

These shifts laid the foundations for the NPP’s historic victory in the 2024 presidential and parliamentary elections. It benefited from growing frustration among the middle class that had become immiserated because of the economic crisis, no less than wide swathes of working people who had borne the brunt of austerity.

Tensions in the cross-class bloc

Perhaps because of its appeal to a cross-class bloc, the NPP coalition remains a mirror on which a diverse electorate can project its hopes and aspirations. Contradictions between different segments of its supporters will surely grow as the NPP takes over government, much as was the case for the Old Left during its encounter with state power. In this context, we must examine the ways in which the NPP has not, in fact, transcended the JVP’s origins, nor the many problems that have long bedevilled the Sri Lankan Left. Indeed, the NPP represents their continuation, albeit in new form.

This is especially true given that, despite its Maoist lineage, the JVP has repeatedly struggled to articulate a clear, wide-ranging programme of redistribution to transform relations between classes and ethnic communities. From its early distrust of the Hill Country Tamils, the party has not addressed the ethno-majoritarian character of the Sri Lankan state. In addition, along with the wider Left, the JVP has not put forward a programme to address the contradictions in the agrarian sector. The agrarian question is crucial given that some two-thirds of the population still claim residence in rural areas. A more robust response would have required an alternative vision grounded in building up semi-autonomous organizations such as cooperatives. Through such rural mobilization, Sri Lanka could have developed alternative methods of accumulation by strengthening linkages between agriculture, fisheries, and industry.

In contrast, economic liberalization since the late 1970s, although supposedly opening up new horizons for middle-class aspirations, has made Sri Lanka increasingly vulnerable to external shocks. This became especially apparent when, at the height of the foreign exchange crisis in 2022, the country was unable to import even essential items such as powdered milk. Consequently, while agrarian issues such as land redistribution remain pressing, they are no longer the only questions on the agenda.

The NPP’s growing base in urban and professional constituencies compels the party to take on political challenges emanating from the sphere of consumption as much as production. This is especially true given that Sri Lanka’s actually existing neoliberal economy, based on tourism and remittances from migrant workers, has revealed so many vulnerabilities since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. Nevertheless, how the middle class would respond to such a much-needed shift would depend on the government’s ability to articulate a new vision of the economy that speaks to underlying demands for meaningful work and upward mobility.

Against elite-led compromise

In other words, the NPP has not found an answer to the age-old question of how to consolidate alliances between radicalized layers of the “petty bourgeoisie” and the working class. In this context, an analysis of the political economy of tourism and mega-infrastructure is essential to understand Sri Lanka’s recent development trajectory. They have become conduits for powerful global forces to exercise even greater leverage over Sri Lanka’s economy.

Building a new bloc of social and class forces committed to an alternative form of development requires a clear understanding of the economic challenges should Sri Lanka try and carve out a new path. Structural parameters include not only the fickleness of foreign revenue sources such as tourism and remittances, but also the need to save foreign exchange on imports while producing more exports. Any attempt to re-balance the economy towards a new strategy of accumulation with the goal of building up domestic wealth would have to strengthen linkages between sectors of the economy, such as food production and its corresponding inputs like boats for the fishing community and fertilizer for cultivators. That, in turn, would require active state investment and planning in areas where market actors are unlikely to obtain immediate profits. But it would also demand a political economic approach to balancing the often-contradictory interests of working people in all their diversity on one hand, and middle-class constituencies on the other.

What can we draw from the NPP’s history to evaluate its potential to respond to these challenges? Much of the debate on the Sri Lankan Left has been pitched at the level of tactics and strategy. The debate about whether struggle is required in the streets or in parliament has become part of an ongoing attempt to distinguish the NPP from its marginal, radical left rivals. But we need a much sharper understanding of the contrast in the world of ideas to clarify the two paths currently available to the Dissanayake government.

One involves compromise with the comprador elite, accepting the current balance of forces and being resigned to the crumbling, Western-led global order. In the medium term at the very least, this would mean a return to the same trajectory as previous governments, rendering the NPP’s victory hollow. In contrast, the 2024 elections could also go down in history as the precursor to a much bigger push to transform Sri Lanka’s economy. But that would require shifting it onto a new trajectory that reflects a clear alternative to neoliberalism.

If the NPP enjoys an initial advantage, it is the extent to which, because of its origins in the Left, it is not predisposed to the vulgar luxury consumption that motivated the ruling-class elites who helped entrench Sri Lanka in relations of dependency. That said, the NPP’s humble origins and reputation for honest governance are no guarantee that it will avoid disastrous economic compromises due to a combination of short-sightedness, weakness, and apathy.

Should it continue on a path of timid compromise, the JVP and NPP will simply become the latest Sri Lankan face of the obsolete centre-left establishment that has enforced austerity in country after country. To avoid this outcome, the Left must develop a vision that prioritizes social mobilization and transforming the relations of production, as much as it does legal reforms and changes to the structures of governance.

Devaka Gunawardena is a political economist and Research Fellow with the Social Scientists’ Association in Sri Lanka. Ahilan Kadirgamar is a political economist and Senior Lecturer at the University of Jaffna.