Nuclear Weapons: What Are They Good For?

China and Russia are reviving one of the most heated debates of the Cold War. That’s not a bad thing.

By Tobin Harshaw

April 8, 2019, 6:00 AM MDT

April 8, 2019, 6:00 AM MDT

Who’s building hypersonic missiles?

Photographer: Tyrone Siu/AFP/Getty Images

With both China and Russia now threatening U.S. global primacy, the world has entered a new era of great-power competition. The struggle is playing out in diplomacy, trade, and politics, of course. But some of its gravest implications are military.

Ukraine and the South China Sea are only the most obvious hot spots. The three countries are vying for influence from East Africa to Latin America to the ever-melting Arctic. And as President Donald Trump made clear with his recent decision to withdraw from America’s 1987 Intermediate-Range Nuclear Weapons Treaty with Russia, the threat of nuclear conflict may be rising again to Cold War levels.

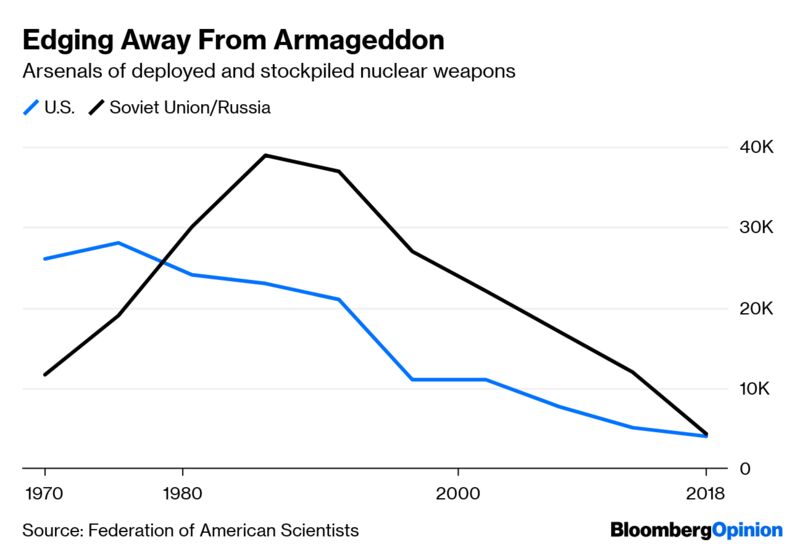

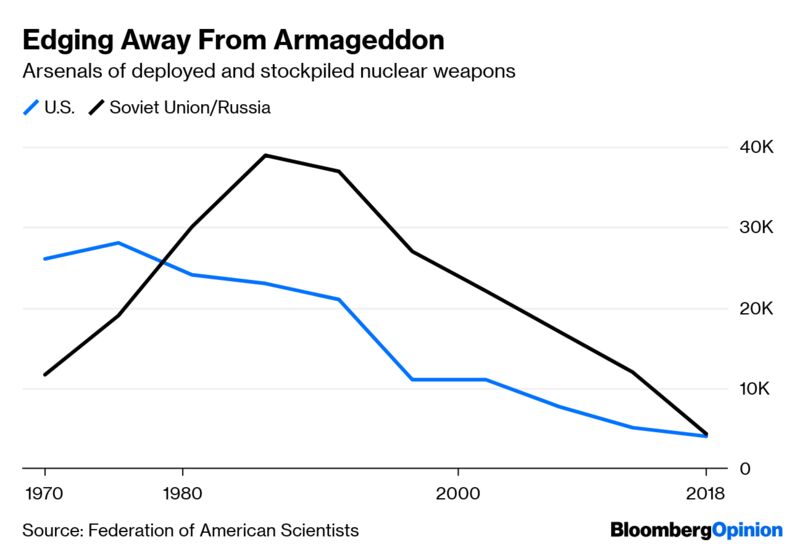

The challenge for today’s military planners is to prevent nuclear war as thoroughly as their Cold War predecessors did. For it’s true that, since 1945, no atomic weapons have been dropped in anger. With the potential exception of the Cuban missile crisis, the possibility never came very close. And over the past three decades, the major powers’ nuclear arsenals have steadily been reduced.

The removal of the ex-Soviet arsenal from the newly independent states in the 1990s was a military and diplomatic success story. And although a handful of countries have joined the nuclear club with small arsenals, only one of them — North Korea — is a rogue state, and no terrorist group has obtained even a dirty bomb.

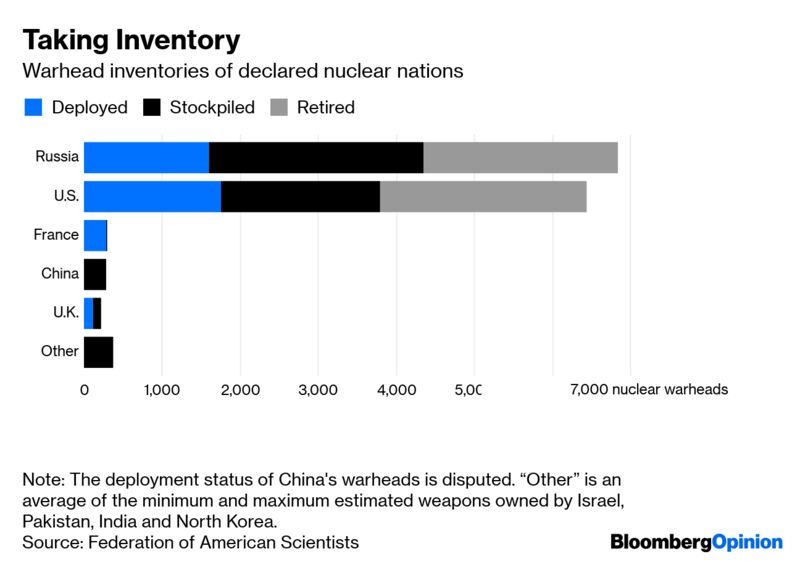

In 1986, nearly 65,000 warheads existed around the globe; today, there are roughly 10,000. And except, again, for North Korea, nuclear-weapons testing has ceased.

Now, all that progress is in danger of being rolled back. With the demise of the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty, new efforts toward nuclear deterrence are needed, with all three major powers involved.

Related: Updating America’s Nuclear Arsenal for a New Age

As it did during the Cold War, the U.S. will want to simultaneously blunt the nuclear threats posed by Russia and China and bolster its own nuclear arsenal for the purpose of deterrence. But today its choices of weaponry will need to be different.

Back when the U.S. stood off against the Soviet Union, deterrence was based largely on the concept of mutually assured destruction. The likelihood of annihilation presumably kept either side from doing something thoughtless. Now, the nuclear powers are increasingly considering a different strategy that involves the use of nuclear weapons with yields low enough to limit their destruction to a discrete battlefield.

Unlike a Russian intercontinental ballistic missile capable of devastating all of New York City, for example, a tactical nuke could be small and precise enough to take out lower Manhattan but leave much of the suburbs unscathed. Such a weapon could be deployed to buy time in fighting a conventional war — say, if Chinese troops were to overrun Taiwan or Russians were to move into the Baltics.

This strategy is one Russia appears to already envision. According to the Trump administration’s recent Nuclear Posture Review, Moscow’s “escalate to de-escalate” scenario for conventional battles involves using tactical nuclear strikes weak enough to make a full-blown atomic response seem disproportionate. The review recommended expanding the U.S. arsenal of battlefield weapons as a “flexible” nuclear option.

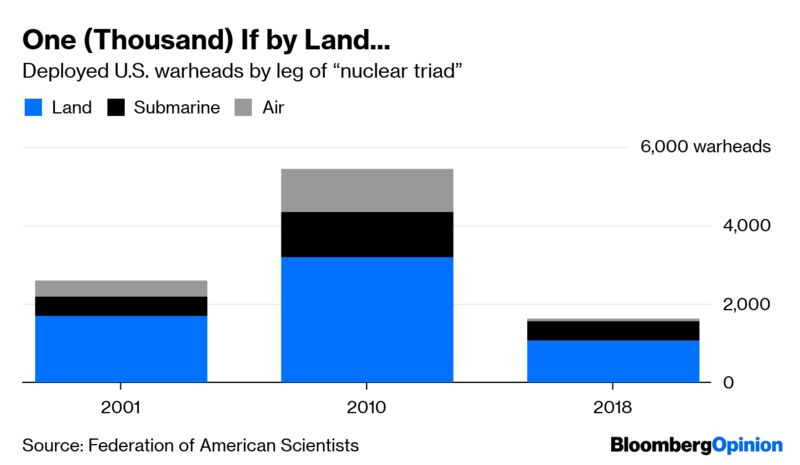

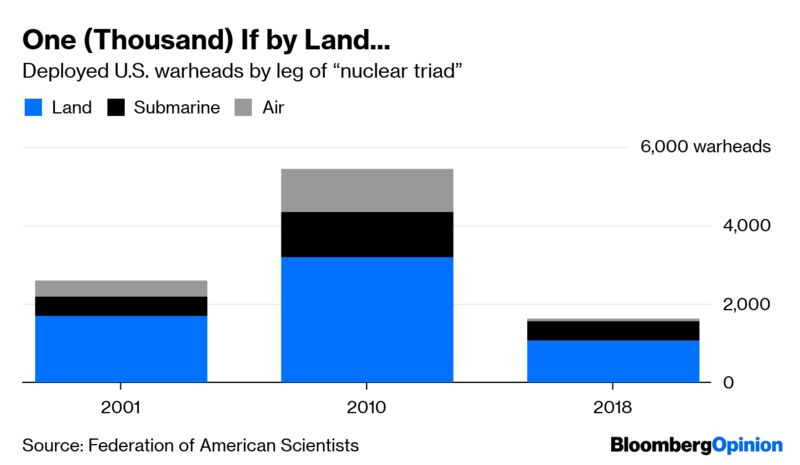

This potential change in posture is leading some U.S. military planners to reconsider its age-old nuclear triad, which relies on weapons positioned on land, at sea and in the air. The land-based weapons, in particular, may no longer be worth the expense. These are the massive intercontinental ballistic missiles held in underground silos in the Great Plains.

The Minuteman III carries up to three thermonuclear warheads, with a total destructive power nearly 100 times that of the bomb dropped on Hiroshima. It is devastatingly accurate, able to strike within 200 yards of its target after an 8,000-mile journey in and out of the atmosphere. But once it is launched, it cannot be turned back. What role is there for such a doomsday machine in a limited nuclear war?

The Air Force has asked Northrop Grumman and Boeing for a new ICBM to replace the Minuteman III, one that could be in place by 2030 and remain viable until at least 2075. Initial cost estimates range from $63 to $85 billion. That’s real money even by Pentagon standards. It would be smarter to spend far less by simply modernizing the current missiles, and to use the savings for increased spending on more flexible weapons.

As far back as 2011, Admiral Michael Mullen, then chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, said, “Certainly I think a decision will have to be made in terms of whether we keep the triad or drop it down to a dyad.”

The air- and especially sea-based legs have become the backbone of the nuclear deterrent: Submarines are virtually invisible to even the most modern detection technology, and the Navy’s newest Trident ballistic missiles are as nearly as accurate as ICBMs. The Air Force is getting a new long-range stealth bomber, the B-21 Raider, which may be able to operate with no human aboard, to replace its decades-old B-1s and B-2s and perhaps its ancient B-52s.

What’s worrisome is that both services are also considering new nuclear-armed cruise missiles that would make it difficult for a target state to tell whether an attack was conventional or nuclear. That would, as former Secretary of Defense William Perry has warned, carry serious risks of miscalculation and escalation. As threats rise and air defenses improve, it may become necessary to build such risky weapons, but we’re not there yet.

Another fraught issue is weaponizing space, which is banned under a 1967 United Nations treaty. Last fall, Vice President Mike Pence said the U.S. is prepared to consider nuclear weapons in orbit on “the principle that peace comes through strength.” Such thinking is premature, but research is needed now on satellite-based lasers and conventional missiles for offensive and defensive purposes.

Alongside efforts to bolster its aggressive nuclear capabilities, the U.S. military continues to work on missile defense — spending more than $40 billion since Ronald Reagan’s so-called Star Wars dream failed to become a reality. The results have been less than impressive. The U.S. has roughly 50 “kill vehicles” intended to defend against a small-scale intercontinental attack of the sort North Korea might attempt, but the success rate in testing is only about 50 percent. A second system based in Eastern Europe since 2016 uses an on-shore version of the Navy’s excellent Aegis combat system and is intended to protect Europe from an Iranian nuclear attack. But it can’t stop longer-range ballistic missiles.

The Pentagon hopes to develop defensive weapons capable of destroying enemy missiles at the launch pad. Theoretically, that should be easier than knocking them out of the sky, but the technical difficulties have yet to be overcome.

The debate over how best to compile a strong nuclear arsenal will continue with every advance in weaponry, as will arguments over how best to achieve deterrence. It’s obvious that nuclear weapons cannot make all war unthinkable. They have failed to prevent any number of 20th-century fights, including the Arab states’ 1973 invasion of Israel, which even then had a clandestine nuclear program. The U.S. arsenal failed to dissuade North Korea from invading South Korea in 1950, or Saddam Hussein from trying to annex Kuwait. Neither Osama bin Laden nor his Islamic State successors seem to have given nuclear weapons a moment’s worry.

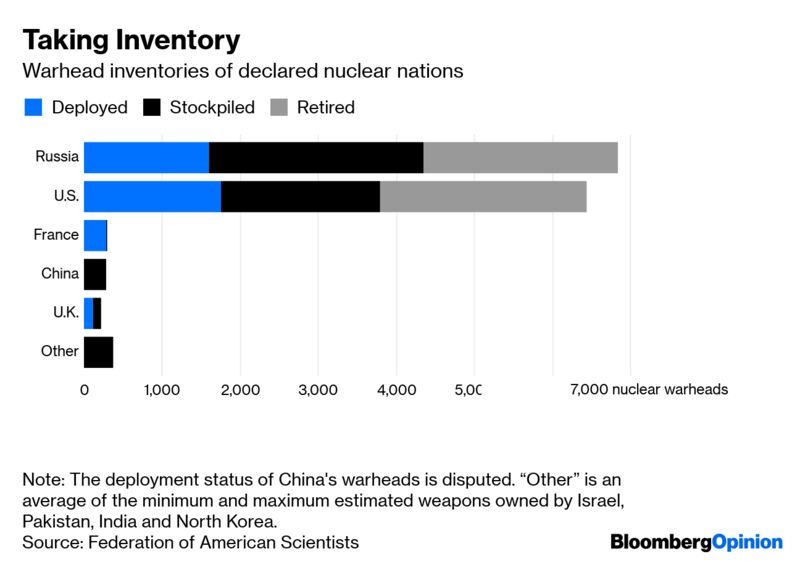

Yet one brutal fact remains as true today as it was in caveman days: If your enemy picks up a rock, you’d better try to find a bigger one of your own. Russia has 4,000-odd nuclear rocks. China has only a few hundred, but it’s racing to build a true nuclear triad and missile-defense systems. Beijing and Moscow are thought to be ahead of the West in developing certain new technologies, including hypersonic missiles that could travel at some two miles per second and can steer themselves after re-entering the earth’s atmosphere.

The Pentagon wants to stay ahead of this escalation, and has the budget to do so — as much as $1 trillion over 30 years to modernize the nuclear arsenal. Nobody wants tensions among the world’s great powers to ever go nuclear. But being prepared for the worst is among the best ways to ensure it will never happen.

With both China and Russia now threatening U.S. global primacy, the world has entered a new era of great-power competition. The struggle is playing out in diplomacy, trade, and politics, of course. But some of its gravest implications are military.

Ukraine and the South China Sea are only the most obvious hot spots. The three countries are vying for influence from East Africa to Latin America to the ever-melting Arctic. And as President Donald Trump made clear with his recent decision to withdraw from America’s 1987 Intermediate-Range Nuclear Weapons Treaty with Russia, the threat of nuclear conflict may be rising again to Cold War levels.

The challenge for today’s military planners is to prevent nuclear war as thoroughly as their Cold War predecessors did. For it’s true that, since 1945, no atomic weapons have been dropped in anger. With the potential exception of the Cuban missile crisis, the possibility never came very close. And over the past three decades, the major powers’ nuclear arsenals have steadily been reduced.

The removal of the ex-Soviet arsenal from the newly independent states in the 1990s was a military and diplomatic success story. And although a handful of countries have joined the nuclear club with small arsenals, only one of them — North Korea — is a rogue state, and no terrorist group has obtained even a dirty bomb.

In 1986, nearly 65,000 warheads existed around the globe; today, there are roughly 10,000. And except, again, for North Korea, nuclear-weapons testing has ceased.

Now, all that progress is in danger of being rolled back. With the demise of the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty, new efforts toward nuclear deterrence are needed, with all three major powers involved.

Related: Updating America’s Nuclear Arsenal for a New Age

As it did during the Cold War, the U.S. will want to simultaneously blunt the nuclear threats posed by Russia and China and bolster its own nuclear arsenal for the purpose of deterrence. But today its choices of weaponry will need to be different.

Back when the U.S. stood off against the Soviet Union, deterrence was based largely on the concept of mutually assured destruction. The likelihood of annihilation presumably kept either side from doing something thoughtless. Now, the nuclear powers are increasingly considering a different strategy that involves the use of nuclear weapons with yields low enough to limit their destruction to a discrete battlefield.

Unlike a Russian intercontinental ballistic missile capable of devastating all of New York City, for example, a tactical nuke could be small and precise enough to take out lower Manhattan but leave much of the suburbs unscathed. Such a weapon could be deployed to buy time in fighting a conventional war — say, if Chinese troops were to overrun Taiwan or Russians were to move into the Baltics.

This strategy is one Russia appears to already envision. According to the Trump administration’s recent Nuclear Posture Review, Moscow’s “escalate to de-escalate” scenario for conventional battles involves using tactical nuclear strikes weak enough to make a full-blown atomic response seem disproportionate. The review recommended expanding the U.S. arsenal of battlefield weapons as a “flexible” nuclear option.

This potential change in posture is leading some U.S. military planners to reconsider its age-old nuclear triad, which relies on weapons positioned on land, at sea and in the air. The land-based weapons, in particular, may no longer be worth the expense. These are the massive intercontinental ballistic missiles held in underground silos in the Great Plains.

The Minuteman III carries up to three thermonuclear warheads, with a total destructive power nearly 100 times that of the bomb dropped on Hiroshima. It is devastatingly accurate, able to strike within 200 yards of its target after an 8,000-mile journey in and out of the atmosphere. But once it is launched, it cannot be turned back. What role is there for such a doomsday machine in a limited nuclear war?

The Air Force has asked Northrop Grumman and Boeing for a new ICBM to replace the Minuteman III, one that could be in place by 2030 and remain viable until at least 2075. Initial cost estimates range from $63 to $85 billion. That’s real money even by Pentagon standards. It would be smarter to spend far less by simply modernizing the current missiles, and to use the savings for increased spending on more flexible weapons.

As far back as 2011, Admiral Michael Mullen, then chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, said, “Certainly I think a decision will have to be made in terms of whether we keep the triad or drop it down to a dyad.”

The air- and especially sea-based legs have become the backbone of the nuclear deterrent: Submarines are virtually invisible to even the most modern detection technology, and the Navy’s newest Trident ballistic missiles are as nearly as accurate as ICBMs. The Air Force is getting a new long-range stealth bomber, the B-21 Raider, which may be able to operate with no human aboard, to replace its decades-old B-1s and B-2s and perhaps its ancient B-52s.

What’s worrisome is that both services are also considering new nuclear-armed cruise missiles that would make it difficult for a target state to tell whether an attack was conventional or nuclear. That would, as former Secretary of Defense William Perry has warned, carry serious risks of miscalculation and escalation. As threats rise and air defenses improve, it may become necessary to build such risky weapons, but we’re not there yet.

Another fraught issue is weaponizing space, which is banned under a 1967 United Nations treaty. Last fall, Vice President Mike Pence said the U.S. is prepared to consider nuclear weapons in orbit on “the principle that peace comes through strength.” Such thinking is premature, but research is needed now on satellite-based lasers and conventional missiles for offensive and defensive purposes.

Alongside efforts to bolster its aggressive nuclear capabilities, the U.S. military continues to work on missile defense — spending more than $40 billion since Ronald Reagan’s so-called Star Wars dream failed to become a reality. The results have been less than impressive. The U.S. has roughly 50 “kill vehicles” intended to defend against a small-scale intercontinental attack of the sort North Korea might attempt, but the success rate in testing is only about 50 percent. A second system based in Eastern Europe since 2016 uses an on-shore version of the Navy’s excellent Aegis combat system and is intended to protect Europe from an Iranian nuclear attack. But it can’t stop longer-range ballistic missiles.

The Pentagon hopes to develop defensive weapons capable of destroying enemy missiles at the launch pad. Theoretically, that should be easier than knocking them out of the sky, but the technical difficulties have yet to be overcome.

The debate over how best to compile a strong nuclear arsenal will continue with every advance in weaponry, as will arguments over how best to achieve deterrence. It’s obvious that nuclear weapons cannot make all war unthinkable. They have failed to prevent any number of 20th-century fights, including the Arab states’ 1973 invasion of Israel, which even then had a clandestine nuclear program. The U.S. arsenal failed to dissuade North Korea from invading South Korea in 1950, or Saddam Hussein from trying to annex Kuwait. Neither Osama bin Laden nor his Islamic State successors seem to have given nuclear weapons a moment’s worry.

Yet one brutal fact remains as true today as it was in caveman days: If your enemy picks up a rock, you’d better try to find a bigger one of your own. Russia has 4,000-odd nuclear rocks. China has only a few hundred, but it’s racing to build a true nuclear triad and missile-defense systems. Beijing and Moscow are thought to be ahead of the West in developing certain new technologies, including hypersonic missiles that could travel at some two miles per second and can steer themselves after re-entering the earth’s atmosphere.

The Pentagon wants to stay ahead of this escalation, and has the budget to do so — as much as $1 trillion over 30 years to modernize the nuclear arsenal. Nobody wants tensions among the world’s great powers to ever go nuclear. But being prepared for the worst is among the best ways to ensure it will never happen.

ALSO SEE

AND THE PERMANENT ARMS ECONOMY TODAY

The Pentagon has decided not to disclose how many nuclear warheads it keeps in its stockpile, such as this W76 thermonuclear ballistic missile warhead.

The Pentagon has decided not to disclose how many nuclear warheads it keeps in its stockpile, such as this W76 thermonuclear ballistic missile warhead.

Last-minute intervention saves JASON government advisory panel from closure

New offer