Arto Luukkanen

The Party of UnbeliefThe Religious Policy ofThe Bolshevik Party, 1917-1929 PDF

The Finnish Historical Society has published this study with the permission,

granted on 18 April 1994, of Helsinki University, Faculty of Theology.

Abstract

Arto Luukkanen

The Party of Unbelief — The Religion Policy of The Bolshevik Party,

1917-1929.

The main objective of this dissertation is to study the religious policy of

the Soviet Bolshevik party during the years 1917-1929 by utilizing

historical methods. The Bolshevik religious ideology was influenced by

Left-Hegelian philosophy, Marxist materialism and the anti-clerical

attitudes of the Russian intelligentsia. The period under examination

can be divided into four separate sections. During the civil war (1917-

1920) the ruling regime limited its official religious policy to legislative

acts in church-state relations and its main political objective was to

isolate the Russian Orthodox church, the ROC. The mission of

executing Soviet religious policy was given to the NKYust's

"Liquidation Committee" and to the Soviet security organs. The

introduction of the early NEP policy (1921-1923) did not automatically

represent a relaxation of the religious policy but, on the contrary, the

Bolshevik government, especially Lenin and Trotsky, engaged in

general attack against the ROC during the so-called "confiscation

conflict". Trotsky and his "Liquidation Committee" conducted this

anti-religious campaign in order to obtain money and to undermine the

role of religions in the Soviet society by fomenting pro-government

schisms inside the religious organizations.

After Lenin lost his grip on power, the "triumvirate" and especially

Stalin outmanoeuvred Trotsky in the anti-religious work by organizing

their own antireligious cabinet (CAP). This change was rationalized by

certain slogans of the high NEP (1924-1927) which underlined the

importance of seeking reconciliation in the Russian countryside.

Moreover, foreign pressure also played into the hands of the

"triumvirate". This policy of appeasing the peasantry also implied a

relaxation in the antireligious campaign. The 12th and 13th party

congresses represented the beginning of the high NEP and of "detente"

in Soviet religious policy. The more moderate party leaders wanted to

stabilize the Russian countryside by making concessions to religion

while at the same time hard-liners attempted to brake the normalcy of

the NEP in this area.

The NEP could not survive the introduction of the Cultural

Revolution (1928-1929). The criticism from the left-opposition

gradually undermined the fundamentals of the NEP's civil peace. Stalin

was also anxious also to utilize this mood in order to get rid of his

"rightist" allies and to this end encouraged the Cultural Revolution by

supporting Komsomol's drive to politicize Soviet society. In the

religious policy former religious political organs were disbanded and

their responsibilities were transferred to the VTsIK. The battle between

moderates, so-called culturalists and hard-liners (interventionists) was

one of the most characteristic features of anti-religious activity at that

time. As a conclusion, it must be stated that the Soviet religious policy

was always dependent on the general political objectives of the party

leaders. The development of the Soviet religious ideology must

6 therefore be studied in association with other major political battles.

It’s possible that I shall make an ass of myself. But in that case one can always get out of it with a little dialectic. I have, of course, so worded my proposition as to be right either way (K.Marx, Letter to F.Engels on the Indian Mutiny)

Wednesday, January 22, 2020

Franklin Dmitryev* and Eugene Gogol**

*Independent researcher, franklin.dmitryev@gmail.com

**Independent researcher, egogol@hotmail.com

Abstract: How can Marx’s ideas help us with the problem of how to make new revolutionary beginnings in a time when the counterrevolution is ascendant, without losing sight of the need to prepare for the equally crucial question of what happens after the revolution? Capitalism has taken various forms as it developed, with the latest shaped by its endemic crisis since the mid-1970s generated by its falling rate of profit. Throughout these stages, the humanism and dialectic of Capital remain prime determinants of allowing Marxist responses not to stop at economic analyses but to release, rather than inhibiting, new revolutionary subjects and directions. Critical for the present moment is to take up Marx’s humanism and dialectic as crucial dimensions of his philosophy of revolution in permanence. This encompasses not alone the famous March 1850 Address to the Communist League, but also the full trajectory of Marx's revolutionary life and thought from the 1844 Economic-Philosophic Manuscripts through Capital to the new moments of Marx's last decade as expressed in his writings on Russia and his Ethnological Notebooks. We trace Marx's theoretical/philosophical concept of permanent revolution in a number of his writings, to confront how various post-Marx Marxists addressed or ignored this dimension of Marx's thought, and explore whether this concept can be seen as central to Marx's body of thought, and can assist in the dual task of needed revolutionary transformation – the destruction of the old (negation) and the construction of the new (the negation of the negation).

Keywords: Karl Marx, revolution, permanent revolution, Leon Trotsky, Mao Zedong, Raya Dunayevskaya, Marxist humanism, women’s liberation

Walter Rodney on the Russian Revolution

Introduction [Excerpt]:

Walter Rodney on the Russian Revolution

Robin D. G. Kelley

During the academic year 1970-71, Walter Rodney, the renowned Marxist historian of

Africa and the Caribbean, taught an advanced graduate course titled “Historians and

Revolutions” at the University of Dar es Salaam, Tanzania, focusing entirely on the

historiographies of the French and Russian Revolutions. This wasn’t your run-of-the-mill

European historiography course. Rodney’s objectives were to introduce students to dialectical

materialism as a methodology for interpreting the history of revolutionary movements, critique

bourgeois histories and their liberal conceits of objectivity, and to draw political lessons for the

Third World. Russia, having experienced the first successful socialist revolution in the world,

figured prominently in the course.1

To prepare, he underwent a thorough review of Russian history in the year or more prior

to the course, reading on the emancipation of the serfs, the rise of the Russian left intelligentsia, the 1905 Revolution, the February Revolution of 1917, the Bolshevik seizure of power inOctober, Lenin’s New Economic Policy, Trotsky’s interpretation of history, and the rise of Stalinism and “socialism in one country.” He read voraciously and systematically, critically

absorbing virtually everything available to him in the English language—from U.S. and British

Cold War scholarship to translations of Soviet historiography. The result was a series of

original lectures that revisited key economic and political developments, the challenges of

socialist transformation in a “backwards” empire, the consolidation of state power, debates

within Marxist circles over the character of Russia’s revolution, and the ideological bases of

historical interpretation. Rather than simply re-narrate well-known events, Rodney took up the

more challenging task of interrogating the meaning, representation, and significance of the

Russian Revolution as a world historical event whose reverberations profoundly shaped Marxist thought, Third World liberation movements, and theories of socialist transformation.

Walter Rodney on the Russian Revolution

Robin D. G. Kelley

During the academic year 1970-71, Walter Rodney, the renowned Marxist historian of

Africa and the Caribbean, taught an advanced graduate course titled “Historians and

Revolutions” at the University of Dar es Salaam, Tanzania, focusing entirely on the

historiographies of the French and Russian Revolutions. This wasn’t your run-of-the-mill

European historiography course. Rodney’s objectives were to introduce students to dialectical

materialism as a methodology for interpreting the history of revolutionary movements, critique

bourgeois histories and their liberal conceits of objectivity, and to draw political lessons for the

Third World. Russia, having experienced the first successful socialist revolution in the world,

figured prominently in the course.1

To prepare, he underwent a thorough review of Russian history in the year or more prior

to the course, reading on the emancipation of the serfs, the rise of the Russian left intelligentsia, the 1905 Revolution, the February Revolution of 1917, the Bolshevik seizure of power inOctober, Lenin’s New Economic Policy, Trotsky’s interpretation of history, and the rise of Stalinism and “socialism in one country.” He read voraciously and systematically, critically

absorbing virtually everything available to him in the English language—from U.S. and British

Cold War scholarship to translations of Soviet historiography. The result was a series of

original lectures that revisited key economic and political developments, the challenges of

socialist transformation in a “backwards” empire, the consolidation of state power, debates

within Marxist circles over the character of Russia’s revolution, and the ideological bases of

historical interpretation. Rather than simply re-narrate well-known events, Rodney took up the

more challenging task of interrogating the meaning, representation, and significance of the

Russian Revolution as a world historical event whose reverberations profoundly shaped Marxist thought, Third World liberation movements, and theories of socialist transformation.

The Right Wing Advances in Militarized Bolivia

Post on: January 22, 2020

Thousands of military and police are controlling the streets of Bolivia in preparation for mobilizations on January 22, the anniversary of the Bolivian constitution and the date on which Evo Morales would have finished his term as President.

Image: Página Siete

It has been two months since a right-wing coup ousted Bolivian President Evo Morales with the help of the US-controlled Organization of American States (OAS). The anti-indigenous and hyper-religious right took power, burning indigenous flags and removing indigenous symbols. The “interim President,” Jeanine Áñez Chávez, was not democratically elected but was sworn into a half empty Congress and left the chambers holding a comically oversized Bible and promising to bring God back into the government. Meanwhile, outside Congress, indigenous workers and peasants participated in massive mobilizations created self-defense committees to protect themselves from right-wing mobilizations and the armed forces. These were repressed heavily, resulting in the deaths of at least 38 people by government estimates.

In the midst of the mobilizations, Evo Morales left the country, first fleeing to Mexico and then beginning a process of getting political asylum in Argentina. Rather than encouraging the resistance, in the midst of the protests Evo Morales tweeted, “I ask my people with great care to respect the peace and not fall into the violence of groups that seek to destroy the rule of law. We cannot fight among Bolivian brothers. I make an urgent call to resolve all differences with dialogue and discussion.”

Since then, the mobilizations have died down and the coup has advanced. Morales has been accused of terrorism and sedition by the coup government, and an arrest warrant has been issued against him. The courts are deciding whether or not the MAS, Evo Morales’ party, will even be allowed to run in the upcoming elections. Now Bolivia has been militarized in preparation for potential demonstrations on January 22, the anniversary of the ratification of Bolivia’s constitution, as well as the day Morales was sworn in as President.

On January 22, the Congress accepted Evo Morales’ resignation: two months and 11 days after he was coerced to give the resignation in the right wing coup that ousted him. Evo Morales’ party, the MAS, holds ⅔ of the Parliament, but a sector of them broke ranks to vote in favor of accepting the resignation. Only a few days ago, the same Congress approved the extension of the coup-President’s term: Añez’s term was scheduled to end today, but now she will remain in power until elections are held in May.

Morales in Argentina

Last week, Evo Morales made a very controversial statement on the radio show “Kawsachun Coca,” owned by the coca planters union. “Before long,” he said, “if I return to Bolivia, we will have to organize popular armed militias, as Venezuela has done.”

And then came the backlash from the Bolivian right sectors, as well as sectors of his own party, the MAS. The statement was even controversial internationally, putting his stay in Argentina at risk. The Argentine Union Civica Radical Party (UCR) presented a bill to reject Morales’ refugee status in response to his statements about the militias.

Faced with such a risk, Morales went back on his words, claiming he didn’t want people to arm themselves with guns and that he wanted actions “within the framework of our uses and customs, and respecting the Constitution.” The UCR said that “if no new statements of this nature occur, they will not insist on the treatment of the bill presented.”

In a press conference Defense Minister Luis Fernando Lopez said, “Bolivia’s people are hurt, and our armed forces outraged.” He said Morales was using “an absolutely terrorist and seditious logic.”

The Coup d’État Advances

Predictably, the right wing took advantage of Morales’ statements, using it as an opportunity to militarize the country in preparation for mobilizations called by social movements and labor organizations led by the MAS. As early as January 16, the police were performing drills in the center of La Paz.

Huge mobilization of the Bolivian military in the center of La Paz, outside San Francisco cathedral.In six days, social movements will be protesting here against the coup. pic.twitter.com/CxUqdV44rv— Ollie Vargas (@OVargas52) January 16, 2020

Police drove through cities with machine guns sticking out of tanks and armored cars. 70,000 police have been mobilized to contain and intimidate potential unrest.

It is important to note that the police have played a key role in the coup—and they have been handsomely rewarded for it: Añez brought their salaries up to the same pay rate as the military. Even the UN had to take notice: “It seems like the police is following the instructions of the far-right in Bolivia,” said United Nations Special Rapporteur Alfred de Zayas.

Since taking office, Añez begun a privatization program. She also invited the Israeli Defense Forces to train the Bolivian security services and yesterday she ordered the closure of Bolivia’s “Anti-imperialist military school” and opened a military school called “Héroes de Ñancahuzú,” in honor of the people who assassinated Che Guevara.

The right wing’s hypocrisy is clear. When they were running against Morales, they talked about democracy and the right to an opposition. Today, their so-called democracy comes hand in hand with repression, militarization, persecution, vindictiveness and, in general, the threat to and violation of the most basic democratic rights, such as the right to free expression and the press.

The massacres of Sacaba, Senkata and Ovejuyo left, according to official figures, 38 families in mourning; hundreds of people were injured, and more than a thousand arrested and imprisoned in November. Today, about 150 young people are still in prison, accused of sedition and terrorism, among other things. In the midst of expulsions of Cuban doctors and foreign journalists, they recently announced that almost 600 former officials of the previous government are being investigated under the cover of “scandalous corruption” that is said to have been committed in the past 14 years.

Áñez’s Militias vs. Morales’ Words

Along with the militarization of the country, the state administered by President Jeanine Áñez has been covering up and protecting semifascist paramilitary groups, such as who appear in a video published by Bolivia Al Airte TV below. These groups call themselves “the resistance” (the “pititas”). These paramilitary groups are made up of the Unión Juvenil Cruceñista (UJC), the Resistencia Juvenil Cochala (RJC), among others, and they act in broad daylight. In fact, Áñez provided them with 15 motorcycles that they had lost during their attacks on indigenous women and anyone who might resemble a member of the MAS.

The OAS, the UN and mainstream media are silent about these right-wing paramilitary groups that continue to terrorize indigenous people and working-class people in Bolivia. Of course, these institutions have a lot to say about the rhetoric of Morales, about democracy under Morales—and nothing to say about the repressive farce of a democracy under Áñez.

There is a Bolivian expression that says that you shouldn’t show your fist to a rival after fleeing from a fight. There is no other way to interpret Morales’ statements.

After his departure from the country, resistance to the new regime was completely spontaneous, even against MAS leaders from different neighborhoods and municipalities. Most important was the mobilization of the people of El Alto who fought the coup, some dying in the repression. They fought despite the lack of support from Morales and the MAS. Now that the mobilizations have been repressed and the peak has passed, Morales talks about militias—now that the embryos of militias have been disbanded.

In this context, the Bolivian courts have not yet decided if the MAS will be allowed to run in the upcoming elections, yet another repressive and anti-democratic aspect of the current regime.

These signs of the regime’s hardening highlight the profoundly reactionary nature of the movement initiated on October 20 by churches, civic groups and the agro-industry. The political right knows that the general elections on May 3 could be lost to the MAS even with its main candidates outlawed. This fear of losing at the ballot box what they have won with the police and the army leads them to militarize “democracy.”

In a statement, the LOR-CI, a socialist group in Bolivia, said:

In the face of the mobilizations of Jan. 22, we rejected the government threats and defended the democratic right of the peasant communities, neighborhood councils, social organizations and working sectors to mobilize. We at the LOR-CI do not commemorate January 22 since the Plurinational State is the result of the MAS pact with the agro-industry and the “media luna” [half moon, referring to the departments of Santa Cruz, Beni, Pando and Tarija, which largely opposed the Morales government]. We are fighting for a workers’ and indigenous peoples’ state, one that advances in the construction of socialism. This Jan. 22, however, we also defend to the end the democratic right of those who want to claim and commemorate the Plurinational State, today threatened by a racist, clerical, police, military and fascist “republican” clique.

EUROPE

FRANCE: THE STRIKE IS HERE TO STAY!

Lawyers are throwing their robes at the feet of the Justice Minister. Workers in the Louvre shut down the world’s ...

Madeleine Freeman

January 22, 2020

EUROPE

HOW DOES THE REVOLUTIONARY LEFT IN FRANCE INTERVENE IN THE STRIKE?

With entire sectors of workers on strike in France, there is ample opportunity for the Left to intervene decisively in ...

Left Voice

January 22, 2020

EUROPE

ANASSE KAZIB: THE SOCIALIST WORKER CAPTIVATING THE FRENCH MEDIA

The strike in France against a planned pension reform has entered its 50th day. One aspect of the movement that ...

Left Voice

January 22, 2020

EUROPE

RANK-AND-FILE WORKERS IN FRANCE ORGANIZE TO CONTINUE THE STRIKE — INTERVIEW WITH DANIELA COBET

France is experiencing the longest strike since 1968. The union bureaucracies are trying to end the strike — but rank-and-file ...

Left Voice

January 22, 2020

EUROPE

THE YELLOW VESTS: RUMBLINGS OF A COMING STORM

The emergence of the Yellow Vests in France shook the regime of an imperialist country to its core. One year ...

Madeleine Freeman

Damien Bernard

January 22, 2020

It’s All A Game To Them

Post on: January 22, 2020

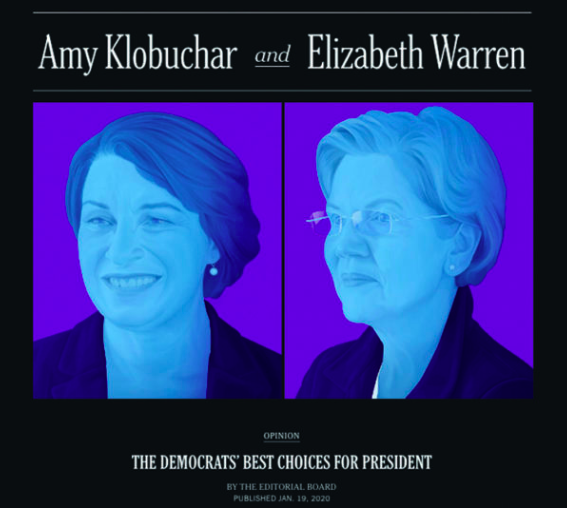

The recent NYT endorsement of Elizabeth Warren and Amy Klobuchar was rolled out like it was a reality show. The bourgeois media keeps revealing that they want to treat politics like it is a game.

The New York Times announced on Sunday that they are endorsing Elizabeth Warren and Amy Klobuchar in the Democratic primary. This decision is surprising both in content and in form. It is certainly unusual for a newspaper to endorse two candidates who are at least nominally opponents. On top of that, Klobuchar is an especially strange choice to endorse, since she is polling at around 3% nationally. Given that the Democratic field is narrowing to essentially four candidates — Biden, Sanders, Warren, and Buttigieg — ahead of the upcoming Iowa Caucus, endorsing a marginal candidate makes the New York Times seem especially out of touch with the current political reality. Additionally, the rationale they gave for endorsing candidates who disagree on several key issues was even more bizarre. They wrote that “both the radical and the realist models warrant serious consideration. If there were ever a time to be open to new ideas, it is now. If there were ever a time to seek stability, now is it.” This “either a or b” approach was widely mocked, even in the pages of the equally mainstream Washington Post. In the face of the political polarization of Trump and Sanders’ populism, the New York Times’ position seems confusing but in essence can be read as: anything but populism.

The endorsement was also strongly criticized for the way that it was released. Instead of following the usual method of announcing an endorsement — publishing an op-ed explaining why a certain candidate should be supported — the New York Times editorial board chose to bring what they called “transparency” to the process. This “transparency” took the form of daily televised episodes of the editorial board sitting down to interview the different candidates, all edited to look as dramatic as possible. This culminated in the endorsement article being published. This unusual rollout has correctly been criticized for revealing what a charade the whole process of endorsement was. The New York Times has revealed that they — and the rest of the bourgeois media — view politics as a game and are happy to treat it as such. They don’t seriously engage with any candidate’s proposals because any proposal that keeps the establishment safe is fine with them. Any serious challenge to the status quo is anathema to them, and they are not opposed to movements designed to win reforms but are actively trying to suppress them. The mission of the Times and all other elements of the capitalist media is simple: to provide legitimacy to the institutions of the state and seek to undermine any attempt to attack them. That is why the Times is so opposed to Trump; it isn’t that they have great political differences with him, but that he delegitimizes the institutions that respectable bourgeois democracy rely upon to justify their hegemony.

All The News That Fits The Narrative

The Times’ editorial board hoped that their series of filmed interviews with each candidate would reveal what rigorous vetting they did in order to make their endorsement. However, what the videos actually reveal is how myopic and out-of-touch the Times is. They are so focused on protecting the most immature understanding of liberal democracy that they are ignoring the political realities of America today. What polls show us that the average person cares about are bread and butter issues like high-cost of health care, the declining economy, and crippling student loan debt. The Times’ vision of how liberal democracy operates can most closely be compared to Schoolhouse Rock, with a very high value placed on compromise and bi-partisan cooperation. Question after question revealed this. They asked Joe Biden about his exercise routine and Andrew Yang about Saturday Night Live in-between asking every single candidate many different variations of “how are you going to do [blank].” There is nothing wrong with interrogating a candidate’s strategy, but when the strategy becomes the program, you no longer have an analysis of what is actually going on. The way that a candidate intends to accomplish what they want to do cannot be substituted for what it is that they want to do. That is respectability politics at its worst because it allows candidates to hide behind decorum and bipartisanship as they enact austerity and imperialism.

The New York Times’ bias was evident in their much maligned interview with Bernie Sanders in which they asked Sanders how his well-attended rallies were different than Donald Trump’s well-attended rallies. This is indicative of the level of intellectual rigour that the editorial board practiced throughout the endorsement process. Indeed, the editorial board made several comparisons between Trump and Sanders, arguing that they would have a similar strategy of conducting themselves as president. This critique erases all notion of program. Though Sanders and Trump have different political programs, the Times would have you believe that because they both challenge the establishment, have large rallies, and don’t want to compromise on their political ideologies, that they are one in the same. But what Sanders and Trump are proposing are very different. As just one example, Trump tried to undo Obamacare while Sanders proposes Medicare for All. Just because Sanders and Trump tap into the same rage at the establishment does not make them similar. This apolitical analysis should remove all respectability and seriousness from the so-called paper of record. While there are many valid reasons to not support Sanders, the fact that he is able to rally mass popular support is certainly not one of them. In fact, the proposals of the Sanders campaign that make him a popular figure — like Medicare For All and student loan forgiveness — are both important demands to support and some of the very reasons that the Times didn’t endorse Sanders.

The whole notion of a newspaper endorsement is based around the idea that the paper is throwing its ideological support behind one candidate over others. By endorsing two candidates with different ideologies, the Times has effectively delegitimized the entire endorsement industry. They have also revealed that they are actively trying to undermine the progressive social movements calling for reforms. The Times just wants a president who will work with Congress, and they’re worried that Sanders might have too much “ideological rigidity and overreach” if elected. That being too ideological when running for president is a criticism reveals all that you need to know about the New York Times and how they feel about politics. It doesn’t matter who wins to them as long as their Aaron Sorkin-esque idea of bourgeois democracy continues unchecked.

The decision to endorse Warren represents this. In the endorsement, the Times attempts to position her as the ‘good’ progressive in the race because she is willing to compromise. They even shouted out her compromise on Medicare For All as a reason why they are more willing to support her over Sanders. The editorial board recognizes that Warren will not present any meaningful changes to the establishment because she is willing to backtrack on even moderate reforms, calls herself a “proud capitalist,” and has a mainstream imperialist foreign policy.

Klobuchar is an interesting choice in that her platform is closer to the Times’ politics, but she is far less of a contender than Warren. It is possible that the editorial board hopes to play kingmaker and revitalize Klobuchar’s campaign in the last few weeks before voting begins. It is also possible that they wanted to be seen as taking a stand without actually wading into the battle between Biden and Sanders. Klobuchar is the type of candidate who in previous contests would have probably fared better than she is now, given that she is a centrist with a strong resume. However, as the Times themselves recognized, the current debate in the Democratic primaries is deeper and more existential than in most years. The question is not which candidate to support, but what sort of platform the party should adopt. Klobuchar represents the right plank of that. By exempting themselves from the actual debate, they allow — at least theoretically — both sides of the Democratic Party to continue reading the Times.

The Gamification of Politics

The way that the Times endorsement was rolled out is important. The endorsement, alone with CNN’s dramatic release of audio the day after the Democratic Debate, shows the gamification of national politics that the bourgeois media has been engaging in. The actual political situation has taken a backseat to the drama of it all. Actual political disagreements and differences have been replaced with feuds. The election has become a reality show, with commenters breathlessly covering who’s up and who’s down. This gamification is just another way that the mainstream media is attempting to sell to us. They have commercialized political unease and are using the increased political awareness in the country to sell ad time and advance their ideology.

There is no greater advocate for the moral authority of journalists than journalists themselves. The self-seriousness of the Times editorial board is palpable throughout the video interviews, as if they are the sole arbitrators of what is true and correct in modern politics. It can be easy to fall into believing, uncritically, the news of so-called objective journalists. But the bourgeois media has as much invested in maintaining the status quo as politicians and business leaders do. We must be critical and carefully analyze the narratives that the bourgeois media try to sell us at all turns. Politics is not a game, and treating it as such does a great disservice to those who are materially impacted by decisions made by the ruling class. Politics matter, and the program of every candidate should be thoroughly interrogated. The New York Times’ mask is off, and we see them for what they are: shallow defenders of the status quo who are deeply afraid of any movement of the working class.

The concept of 'National Bolshevism': An interpretative essay

Erik Van Ree

Journal of Political Ideologies

Volume 6, 2001 - Issue 3

Pages 289-307 | Published online: 04 Aug 2010

The concept of 'National Bolshevism' is mainly used in studies of twentieth-century German and Russian political radicalism. It has been subject to considerable inflation. The present article presents a case for a restrictive definition. National Bolshevism can most properly be defined as that radical tendency which combines a commitment to class struggle and total nationalization of the means of production with extreme state chauvinism. Definitional strictness is not only justified by the historical sources of the term in Germany and Russia. A further advantage of a narrow definition is that it helps us get important distinctions among nationalist and communist movements and states into focus. It is also helpful in bringing out a remarkable asymmetry between the propensity of nationalists and communists to adopt each other's programme.

Erik Van Ree

Journal of Political Ideologies

Volume 6, 2001 - Issue 3

Pages 289-307 | Published online: 04 Aug 2010

The concept of 'National Bolshevism' is mainly used in studies of twentieth-century German and Russian political radicalism. It has been subject to considerable inflation. The present article presents a case for a restrictive definition. National Bolshevism can most properly be defined as that radical tendency which combines a commitment to class struggle and total nationalization of the means of production with extreme state chauvinism. Definitional strictness is not only justified by the historical sources of the term in Germany and Russia. A further advantage of a narrow definition is that it helps us get important distinctions among nationalist and communist movements and states into focus. It is also helpful in bringing out a remarkable asymmetry between the propensity of nationalists and communists to adopt each other's programme.

Communist Upbringing under Stalin: The Political Socialization and Militarization of Soviet

Youth, 1934-1941

Seth Bernstein

Doctor of Philosophy

Department of History

University of Toronto

2013

Abstract:

In 1935 the Communist Youth League (Komsomol) embraced a policy called

“communist upbringing” that changed the purpose of Soviet official youth culture. Founded in 1918, the Komsomol had been an organization of cultural proletarianization and economic

mobilization. After the turmoil of Stalin’s revolution from above, Soviet leaders declared that thecountry had entered the period of socialism. Under the new conditions of socialism, including the threat of war with the capitalist world, “communist upbringing” transformed the youth league into an organization of mass socialization meant to mold youth in the shape of the regime.

The key goals of “communist upbringing” were to broaden the influence of Soviet

political culture and to enforce a code of “cultured” behavior among youth. Youth leaders

transformed the Komsomol from a league of young male workers into an organization that

included more than a quarter of Soviet youth by 1941, incorporating more adolescents, women, and non-workers. Employing recreation, reward and disciplinary practices that blurred into repression, mass socialization in the Komsomol attempted to create a cohort of “Soviet” youth—sober, orderly, physically strong and politically loyal to Stalin’s regime.

The transformation of youth culture under Stalin reflected a general shift in Stalinist

social policies in the mid-1930s. Historians have argued whether this turn was a conservative

iii retreat from Bolshevik ideals or the use of apolitical modern state practices in the service of

socialism. This dissertation shows that while youth leaders were intensely interested in modern state practices, they made these practices into central elements of Soviet socialism. Through the Komsomol, youth became a resource for the state to guide along the uncertain and dangerous road to the future of communism. Reacting to domestic and international crises, Stalinist leaders created a system of state socialization for youth that would last until the fall of the Soviet Union.

Youth, 1934-1941

Seth Bernstein

Doctor of Philosophy

Department of History

University of Toronto

2013

Abstract:

In 1935 the Communist Youth League (Komsomol) embraced a policy called

“communist upbringing” that changed the purpose of Soviet official youth culture. Founded in 1918, the Komsomol had been an organization of cultural proletarianization and economic

mobilization. After the turmoil of Stalin’s revolution from above, Soviet leaders declared that thecountry had entered the period of socialism. Under the new conditions of socialism, including the threat of war with the capitalist world, “communist upbringing” transformed the youth league into an organization of mass socialization meant to mold youth in the shape of the regime.

The key goals of “communist upbringing” were to broaden the influence of Soviet

political culture and to enforce a code of “cultured” behavior among youth. Youth leaders

transformed the Komsomol from a league of young male workers into an organization that

included more than a quarter of Soviet youth by 1941, incorporating more adolescents, women, and non-workers. Employing recreation, reward and disciplinary practices that blurred into repression, mass socialization in the Komsomol attempted to create a cohort of “Soviet” youth—sober, orderly, physically strong and politically loyal to Stalin’s regime.

The transformation of youth culture under Stalin reflected a general shift in Stalinist

social policies in the mid-1930s. Historians have argued whether this turn was a conservative

iii retreat from Bolshevik ideals or the use of apolitical modern state practices in the service of

socialism. This dissertation shows that while youth leaders were intensely interested in modern state practices, they made these practices into central elements of Soviet socialism. Through the Komsomol, youth became a resource for the state to guide along the uncertain and dangerous road to the future of communism. Reacting to domestic and international crises, Stalinist leaders created a system of state socialization for youth that would last until the fall of the Soviet Union.

Lenin’s Marxism*by Wolfgang Küttlertranslated by Loren Balhorn

Beginning in the early 1980s, Georges Labica worked towards a >renewal of Leninism<

against the dogma of Leninism that ruled in state socialism (1986, 123). He emphasized a

strand of thought in the Leninian tradition that avoids claims to a model character

seeking to raise >the empirical evidence of an exceptional historical situation to that of a

generality<, but instead seeks to serve as the foundation >of a political praxis<, which

works towards the realisation of a >communist revolution […] in conjunctures of a

necessarily extraordinary nature< (ibid.). He calls this type of renewing critique, which

works towards a constructive turn in the engagement with Lenin’s legacy, the >work of

the particular< (116). It requires historical concretization as well as critical evaluation of

Lenin’s >interventions< and their consequences for the further development of Marxism

(117).

The >warm stream, hopeful for change< (Mayer 1995, 300) that managed to survive,

against all odds, from Lenin to Gorbachev can nevertheless hardly conceal the fact that

Marxism >was in rapid retreat< (Hobsbawm 2011, 385) long before the emergence of

the >post-communist<, or rather >post-Soviet< situation (Haug 1993). This retreat could

also be observed in how >Soviet orthodoxy precluded any real Marxist analysis of what

had happened and was happening in Soviet society< (Hobsbawm 2011, 386). While

Marx’s analysis and critique of capitalism has retained its validity, reception of Lenin has

become even more overshadowed by Stalinism and its victims since 1989/91. Wolfgang

Ruge understands the tragedy of Lenin in that >he achieved a great amount, but what he

achieved did not correspond to that which he intended whatsoever<, and that his goal,

ultimately >overrun< by history, cost >millions of human lives< (2010, 398).

Nevertheless, the more Lenin is evaluated in light of the failure of Soviet state socialism

since 1989/91, including by Marxists and leftists, the more urgent a historical-critical

reconstruction of his views becomes.

This contribution first addresses the meaning of Lenin in terms of difference and

continuity with Marx on one hand, and in terms of the official Marxism-Leninism (ML)

canonised by Stalin on the other. Proceeding from the end of this epoch, the further

question of the general tendencies of development constituting the context in which

Lenin’s work and historical impact stand at the beginning of the 21st century, an epoch

characterised by conditions of global capitalism resting on the foundation of high-tech

forces of production, will also be addressed.

Canadian Trotskyism and the Legacy of James P. Cannon

photo James Patrick Cannon, SWP (Socialist Workers Party) local New York

Revolutionary socialists in Canada and the United States began organizing a revolutionary workers’ party around the same time. This occurred in the wake of World War I. The new organizations adopted the name Communist Party, in solidarity with the leading force in the Russian Revolution and in support of the leaders of the world’s first workers’ state, the Soviet Union. In Canada many members of the new party came from the Socialist Party of Canada and from the Social Democratic Party of Canada. In the United States, many of them came out of the Socialist Party of Eugene Debs and from the syndicalist Industrial Workers of the World, like James P. Cannon, who was a Wobbly before he became a Bolshevik. There were many internal tendencies and factions inside the new CPs, until Moscow stamped out internal democracy and required affiliates to the Comintern to expel all opponents of Joseph Stalin. In the USSR, many of Stalin’s political opponents were not just expelled or exiled; they were murdered. Historians say that Stalin killed more Communists than Adolf Hitler did.

Founding leaders of the Communist Party of Canada were Jack MacDonald and Maurice Spector. They worked closely with the leaders of the CP USA, like James P. Cannon and William Z. Foster. Spector and Cannon were delegates to the Sixth Congress of the Communist International in Moscow in 1928.

Spector accidentally got hold of a copy of Trotsky’s “Critique of the Draft Programme of the Communist International,” which criticized the position of Nikolai Bukharin and Joseph Stalin. It especially exposed the anti-Marxist theory of “socialism in one country.” This critique became a basis of the International Left Opposition. In a truly prophetic statement, Trotsky warned that if the Communist International adopted socialism in one country, it would inevitably lead to the nationalist and reformist degeneration of every Communist Party in the world. His prediction—which was ridiculed by the Stalinists at the time—was proved correct. Cannon reported what happened on that fateful occasion:

Through some slip-up in the apparatus in Moscow, which was supposed to be airtight, this document of Trotsky came into the translating room of the Comintern. It fell into the hopper, where they had a dozen or more translators and stenographers with nothing else to do. They picked up Trotsky’s document, translated it and distributed it to the heads of the delegations and the members of the program commission. So, lo and behold, it was laid in my lap, translated into English! Maurice Spector, a delegate from the Canadian party, and in somewhat the same frame of mind as myself, was also on the program commission and he got a copy. We let the caucus meetings and the Congress sessions go to the devil while we read and studied this document. Then I knew what I had to do, and so did he. Our doubts had been resolved. It was as clear as daylight that Marxist truth was on the side of Trotsky. We had a compact there and then—Spector and I—that we would come back home and begin a struggle under the banner of Trotskyism. (1)

Socialism in One Country: A Study of Pragmatism and Ideology in the Soviet 1920s

Michael Bensley

Table of Contents:

Introduction: p.3

I. War Communism: p.10

II. Lenin's Final Years: p.23

III. Interregnum: p.38

IV. Socialism in One Country as Theory: p.61

V. Socialism in One Country in Context: p.74

Conclusion: p.96

Bibliography: p.104

INTRODUCTION (EXCERPT)

Michael Bensley

Table of Contents:

Introduction: p.3

I. War Communism: p.10

II. Lenin's Final Years: p.23

III. Interregnum: p.38

IV. Socialism in One Country as Theory: p.61

V. Socialism in One Country in Context: p.74

Conclusion: p.96

Bibliography: p.104

INTRODUCTION (EXCERPT)

Bolshevik policy, upon seizure of power, had

associated itself with the concept of internationalism.

The principle was that the revolution should only

begin in Russia and that the western nations would,

in consequence, revolt as well. The economic aid

that western Europe was expected to donate to

their Russian partners was crucial. This was

especially true for Trotsky who, in his original capacity,

could not imagine any other course of action

other than his 'permanent revolution,' as first set out in

Results and Prospects (1906).5

In the

years which followed the First World War, the western nations

mainly stabilised. In consequence, the regime had

to abandon expectations of further insurrection

the question of whether a country could attempt to reach socialism alone.

The Russian situation,

primarily the backwardness of her industrial development, was another

pertinent issue to be

considered. Leon Trotsky, in an article in Pravda of May 1922 compared the

Soviet Union to a 'besieged fortress,' stating that during such a time of

political and economic isolation from the rest of the world, it was necessary

for the state to ensure unity at any cost.7

The political structures which

developed had ensured the dominance of the Bolsheviks as the only legitimate

party. A level of naivety existed intheir actions, as well as authoritarian

tendencies. Early policies such as 'War Communism' had been carried out in a

callous manner, with scant regard for the human cost. 'The descent into chaos'

which ensued, the excesses and trespasses into human life, had introduced a

framework which could be described as a 'Partocracy'.8

In 1921 the New Economic Policy was introduced. Whether this was a retreat

on the same lines as

the Brest-Livotsk treaty of 1918, (which withdrew the Bolsheviks from the

war against the Central

Powers), or more a pragmatic manoeuvre, is a question which shall be

explored. However, in Lenin's

last years of control, the party would go on to solidify its monopoly of

power. With such events as

the Social Revolutionary trials of 1922, the state had completed its path

towards authoritarianism. It

has been argued that the manner in which events which brought this on. The

idea being that Lenin had to operate in a difficult climate and had to enforce the

one-party state as a temporary measure to ensure the survival of the regime.

This would ultimately lead us to the conclusion that such concepts as 'Workers'

Democracy' reflected his original intentions, if the situation had not dictated

otherwise.9

Of course, historians who take ideology

as a primary factor in the way that the early Soviet Republic developed, have

commented on the economic 'retreat' of introducing NEP being countered with

political tightening.10

This would explain why Lenin had

dealt with his political opponents in this time in such a brutal fashion.

With Lenin's departure from leadership, due to a series of strokes, the

disunity of the leadership had

begun to unravel. As will be discussed in the course of this dissertation,

Stalin had been able to

secure a large number of positions in the state apparatus. His domination

of the bureaucracy

became a crucial factor. Through such organs as the Secretariat he had been

able to manipulate the

Party Congresses, so that the overwhelming majority of voting delegates came

in line with the

leadership, regardless of where the party cells placed their allegiance.

This had been of enormous

importance in the conflict with Trotsky's opposition.11

When Trotsky introduced the 'New Course' (1923), a criticism of the

inflated bureaucracy and the

excesses which had formed as a result of this, a debate began which would

see Stalin enter the field

of theory himself, with such works as The Foundations of Leninism (1924).

With Lenin's death, Stalin

was able to interpret freely many of the former master's ideas and twist

them in such a way that he

could use them to back up any attack. In the fight against 'Trotskyism',

the idea of 'socialism in one

country' came about. Initially, the idea of economic development within

isolated circumstances was

conceptualised by Nikolai Bukharin, but it would later be mentioned in a

pamphlet by Stalin, The

October Revolution and the Tactics of the Russian Communists (1924).12

To ascertain how it was that Stalin was able to take a few lines of Lenin's

previous works and

transform them in such a way as to develop his own body of ideas is crucial

in understanding the

discourse of events in the 1920s. The course of this work will therefore

examine both the context in

which 'socialism of one country' was conceived, and its relative value in

practice. It is easy to

espouse the view that his theory was 'a mere smoke-screen for a clash of

personal ambitions.'13 As

Isaac Deutscher, in his political biography Stalin reminds us, 'No doubt

the personal rivalries were a

strong element in it. But the historian who reduced the whole matter to

that would commit a

blatant mistake.'14 Indeed, as much as it could be argued that the whole

matter was simply to attack

Trotsky's 'permanent revolution' as a counter-thesis of sorts, it had other

properties.

Of course, Bukharin's view of building socialism in Russia alone was far

more geared towards slow

and considered development. By utilising NEP, the state could take a path

towards socialism which

would not have the disastrous outcomes which had become associated with

'War Communism'.15 It

will strike the reader that, for all the caution that Stalin would decree

in the mid-1920s, he ultimately

embarked on the 'revolution from above' and the 'great break.' The main

reasons why this had

occurred is the topic for the last chapter of this dissertation. Suffice it

is to say, the impact of varying

political and socio-economic crises, which occurred from 1926 onwards, had

a fundamental effect on

the regime and upon those who ruled it.