Fishers are one of the poorest professions in Indonesia, yet they are one of the happiest

Indonesia's status as a maritime country seemingly does not guarantee that its fishers live prosperously. My recent study, analysing data from the 2017 National Socioeconomic Survey (SUSENAS), shows fishers are one of the poorest professions in Indonesia.

As many as 11.34% of people in Indonesia's fisheries sector are classified as poor. That's a higher rate than in other sectors such as restaurant services (5.56%), building construction (9.86%) and waste sorting (9.62%).

As a result, the number of young people who want to work as fishers has declined. Data from the Indonesian Statistics Bureau (BPS) show a sharp decrease in households involved in capture fisheries, from 2 million in 2000 to 966,000 in 2016.

This has occurred not only in Indonesia but also in other parts of the world. In 2016, the Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO) reported a continuous decline of workers in the capture fisheries sector. In Europe, the number of fishers fell from 779,000 to 413,00 between 2000 and 2013. A similar trend can be seen in North America and Oceania.

Policies that limit overfishing, along with the advancement of technologies that replace the role of fishers, seem to be the cause of this decline.

A number of scholars argue that low income, extreme weather at sea and being far away from family for a long time have turned the profession into one that is dangerous and unattractive.

However, research I conducted in 2018 found this does not apply to Indonesian fishers. Amid poverty and uncertainty about catches, Indonesian fishers seem to be happier than other professions in the agriculture sector.

Measuring the happiness of fishers

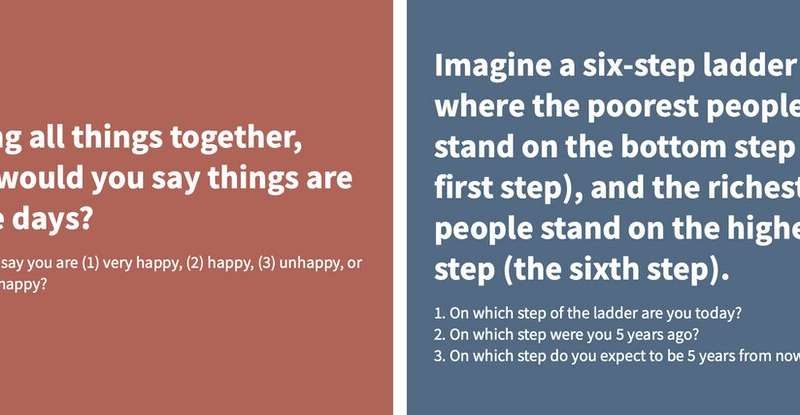

Our team conducted a statistical analysis of the welfare status of fishers, represented by socioeconomic data from the 2012 and 2015 Indonesian Family Life Survey (IFLS).

The IFLS questionnaire also contained an open survey for fishers, asking them how happy they felt or would feel at present, five years ago and five years ahead.

Even though they are one of the most likely to slide under the poverty line, our analysis concludes there is no strong evidence that fishers are less happy than those in other professions.

Instead, many other aspects displayed a stronger correlation to happiness rather than just their status as fishers—such as education level, marriage status and health condition.

One reason that might explain this result is the nature of their profession, which allows them to enjoy more time outdoors, on the open sea.

Past studies suggest aspects such as "adventure", "freedom" and "activities in nature" act as a form of therapy for fishers.

For instance, research from the University of Rhode Island found roaming in calm seas helped fishers in the Caribbean—such as those in Cuba and Haiti—develop very good social relations and a healthy mental state.

Another study, by researchers at East Carolina University in the United States, describes how many former fishers in Puerto Rico chose to return to work in the open sea as a form of therapy after feeling exhausted by years spent in administrative jobs.

Particularly for Indonesian fishers who employ workers, this "therapy" seems to have a stronger effect as they have to work less and can spend more time enjoying nature.

In our survey, fishers also showed higher optimism than other professions in the agriculture sector about their projected economic situation in five years' time.

The above factors might explain why, even in poverty, Indonesian fishers still perceive their living conditions as being on par with other professions, perhaps even one that is worth pursuing for years to come.

The future of the fishery sector

However happy Indonesian fishers are, statistics still show fewer and fewer people are choosing fisheries as a profession.

This means the government has the important task of increasing the welfare of fishers for the sake of this profession's future.

One thing the government can do is issue better regulations for open-access capture fisheries and policies to protect small-scale fishers.

If the government fails to pay attention to this, large fishing vessels will continue to exploit Indonesian waters, which ultimately reduces the catch of traditional fishers.

Government support to increase fishers' welfare—for instance, by providing insurance for small-scale fishers – is also a must for this highly uncertain profession.

Being a fisher might be a happy job, but it would be meaningless if no one is left to continue this profession in the future.

Provided by The Conversation

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.