How To Tame a Fox—and Build a Dog

The amazing true story of how a pair of scientists condensed the domestication process by thousands of years and made foxes every bit as loyal and tame as dogs

By Lee Dugatkin & Lyudmila Trut

Photos by Irena Pivovarova & Irena Muchamedshina

Suppose you wanted to build the perfect dog from scratch. What would be the key ingredients in the recipe? Loyalty and smarts would be musts. Cute would be as well, perhaps with gentle eyes, and a curly, bushy tail that wags in joy just in anticipation of your appearance. And you might toss in a mutt-like mottled fur that seems to scream out "I may not be beautiful, but you know that I love you and I need you."

The thing is, you needn't bother building this. Lyudmila Trut and Dmitri Belyaev have already built it for you. The perfect dog. Except it's not a dog, it's a fox. A domesticated one. They built it quickly—mind-bogglingly fast for constructing a brand new biological creature. It took them less than sixty years, a blink of evolutionary time compared to the time it took our ancestors to domesticate wolves to dogs. They built it in the often unbearable minus 40F cold of Siberia, where Lyudmila and, before her, Dmitri have been running one of the longest, most incredible experiments on behaviour and evolution ever devised. The results are adorable tame foxes that would lick your face and melt your heart.

Many articles have been written about the fox domestication experiment, but a new book, How To Tame a Fox {and Build a Dog} (2017, University of Chicago Press), from which this article is adapted, is the first full telling of the story. The story of the lovable foxes, the scientists, the caretakers (often poor locals who devoted themselves to work they never fully understood, but would sacrifice everything for), the experiments, the political intrigue, the near tragedies and the tragedies, the love stories, and the behind-the-scenes doings. They're all in there.

It started back in the 1950s, and it continues to this day, but for just a moment travel back with us to 1974.

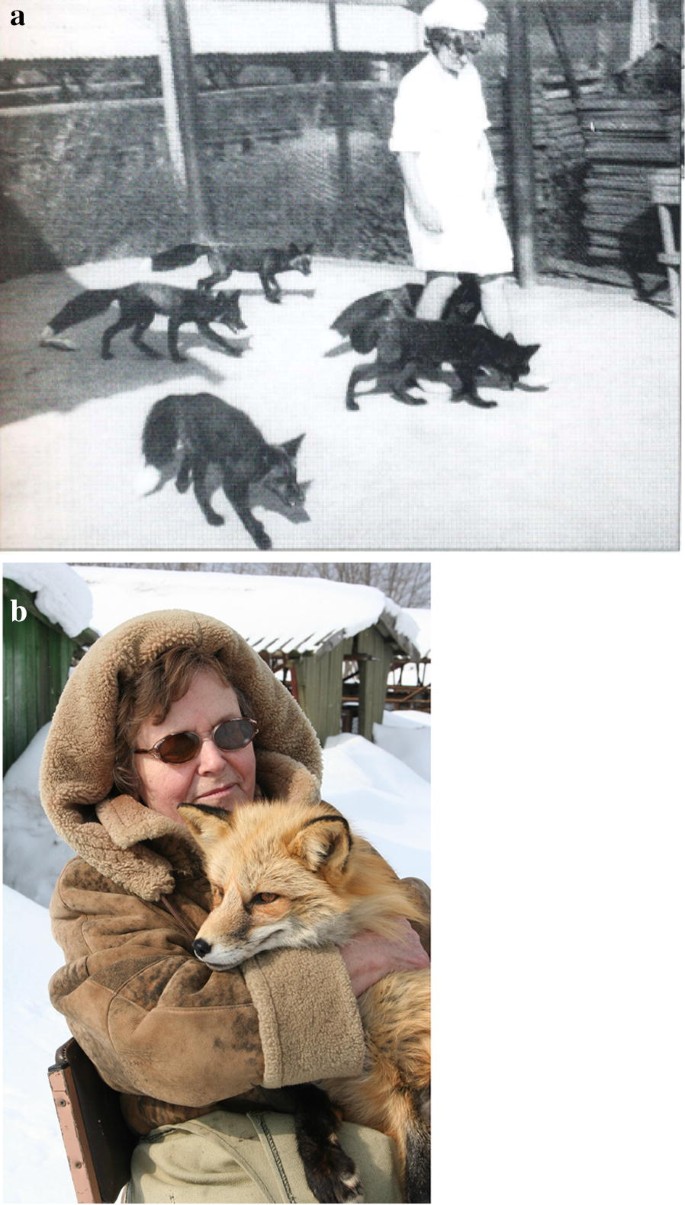

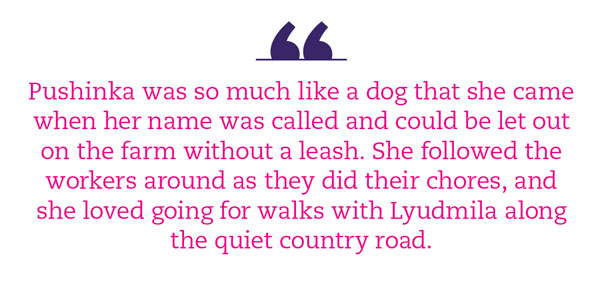

One clear, crisp spring morning in that year, with the sun shining on the not yet melted winter snow, Lyudmila moved into a tiny house on the edge of an experimental fox farm in Siberia with an extraordinary little fox named Pushinka, Russian for "tiny ball of fuzz." Pushinka was a beautiful female with piercing black eyes, silver-tipped black fur, and a swatch of white running along her left cheek. She had recently celebrated her first birthday, and her tame behaviour and dog-like ways of showing affection made her beloved by all at the fox farm. Lyudmila and her fellow scientist and mentor Dmitri Belyaev had decided that it was time to see whether Pushinka was so domesticated that she would be comfortable making the great leap to becoming truly domestic. Could this little fox actually live with people in a home?

Dmitri Belyaev was a visionary scientist, a geneticist working in Russia's vitally important commercial fur industry. Research in genetics was strictly prohibited at the time Belyaev began his career, and he had accepted his post in fur breeding because he could carry out studies under the cover of that work. 22 years before Pushinka was born, he had launched an experiment that was unprecedented in the study of animal behaviour. He began to breed tame foxes. He wanted to mimic the domestication of the wolf into the dog, using the silver fox, which is a close genetic cousin of the wolf, as a stand-in. If he could basically turn a fox into a dog-like animal, he might solve the long-standing riddle of how domestication comes about. Perhaps he would even discover important insights about human evolution; after all, we are, essentially, domesticated apes.

Belyaev's plan for the experiment was audacious. The domestication of a species was thought to happen gradually, over thousands of years. How could he expect any significant results, even if the experiment ran for decades? And yet, here was a fox like Pushinka, who was so much like a dog that she came when her name was called and could be let out on the farm without a leash. She followed the workers around as they did their chores, and she loved going for walks with Lyudmila along the quiet country road that ran by the farm on the outskirts of Novosibirsk, Siberia. And Pushinka was just one of the hundreds of foxes they had bred for tameness.

By moving into the house on the edge of the farm with Pushinka, Lyudmila was taking the fox experiment into unprecedented terrain. Their 15 years of genetic selection for tameness in the foxes had clearly paid off. Now, she and Belyaev wanted to discover whether by living with Lyudmila, Pushinka would develop the special bond with her that dogs have with their human companions. Except for house pets, most domesticated animals do not form close relationships with humans, and by far the most intense affection and loyalty forms between people and their dogs. What made the difference? Had that deep human-animal bond developed over a long time? Or might this affinity for people be a change that could emerge quickly, as with so many other changes Lyudmila and Belyaev had seen in the foxes already? Would living with a human come naturally to a fox that was so domesticated?

Lyudmila had chosen Pushinka to be her companion within moments of first setting eyes on her, when she was an adorable little three-week-old pup frolicking with her brothers and sisters. When Lyudmila looked into Pushinka's eyes, she felt an intense sense of connection, more than with any fox before. Pushinka also showed a remarkable enthusiasm for human contact. She would wag her tail furiously with excitement whenever Lyudmila or one of the farm workers came near her, whimpering with glee and looking up eagerly at them with an unmistakable request that they stop and pet her. No one could walk by her without doing so. Lyudmila had decided to move Pushinka into the house after she had turned one year old, mated, and was carrying a litter of pups. That way, Lyudmila would be able to observe not only how Pushinka adjusted to living with her, but whether pups born in the company of humans might socialize differently than other pups born on the farm. On March 28, 1975, ten days before she was due to deliver, Pushinka was taken to her new home.

Lyudmila had chosen Pushinka to be her companion within moments of first setting eyes on her, when she was an adorable little three-week-old pup frolicking with her brothers and sisters. When Lyudmila looked into Pushinka's eyes, she felt an intense sense of connection, more than with any fox before. Pushinka also showed a remarkable enthusiasm for human contact. She would wag her tail furiously with excitement whenever Lyudmila or one of the farm workers came near her, whimpering with glee and looking up eagerly at them with an unmistakable request that they stop and pet her. No one could walk by her without doing so. Lyudmila had decided to move Pushinka into the house after she had turned one year old, mated, and was carrying a litter of pups. That way, Lyudmila would be able to observe not only how Pushinka adjusted to living with her, but whether pups born in the company of humans might socialize differently than other pups born on the farm. On March 28, 1975, ten days before she was due to deliver, Pushinka was taken to her new home.

The 700-square-foot house had three rooms in addition to a kitchen and bathroom. Lyudmila had moved a bed, a small couch, and a desk into one room to serve as her bedroom and office combined, and she had built a den in another room for Pushinka. The third room was used as a common area, furnished with a few chairs and a table, where Lyudmila ate her meals and where, on occasion, research assistants or other visitors could gather. Pushinka would be free to roam throughout.

When Pushinka arrived early in the morning of the first day, she began racing around the house, in and out of rooms, highly agitated. Normally, pregnant foxes so close to giving birth spend most of their time lying down in their dens, but Pushinka paced and paced from one room to the other. She'd scratch at the wood chips that lined her den floor and lie down briefly, but then she'd jump right back up again and make another circuit of the house. Though she was comfortable with Lyudmila and came over to her often for some petting, Pushinka was clearly unsettled. These strange new surroundings seemed to be causing her extreme anxiety. She wouldn't eat anything all day except for a small piece of cheese and an apple that Lyudmila had brought with her for her own snack. That afternoon, Lyudmila was joined by her daughter, Marina, and Marina's friend, Olga. The girls wanted to be there for Pushinka's big move-in day. At about 11:00 p.m., with Pushinka still pacing around the house, the three of them turned in for the night, the two girls lying down on the floor under blankets next to Lyudmila's bed. To their great surprise and Lyudmila's relief, as they began to drift off to sleep, Pushinka silently sneaked into their room and lay down right alongside the girls. Then, she, too, finally relaxed and went to sleep.

When Pushinka arrived early in the morning of the first day, she began racing around the house, in and out of rooms, highly agitated. Normally, pregnant foxes so close to giving birth spend most of their time lying down in their dens, but Pushinka paced and paced from one room to the other. She'd scratch at the wood chips that lined her den floor and lie down briefly, but then she'd jump right back up again and make another circuit of the house. Though she was comfortable with Lyudmila and came over to her often for some petting, Pushinka was clearly unsettled. These strange new surroundings seemed to be causing her extreme anxiety. She wouldn't eat anything all day except for a small piece of cheese and an apple that Lyudmila had brought with her for her own snack. That afternoon, Lyudmila was joined by her daughter, Marina, and Marina's friend, Olga. The girls wanted to be there for Pushinka's big move-in day. At about 11:00 p.m., with Pushinka still pacing around the house, the three of them turned in for the night, the two girls lying down on the floor under blankets next to Lyudmila's bed. To their great surprise and Lyudmila's relief, as they began to drift off to sleep, Pushinka silently sneaked into their room and lay down right alongside the girls. Then, she, too, finally relaxed and went to sleep.

As Lyudmila would discover over the course of many months with Pushinka, the lovable little fox would not only become perfectly comfortable living with her, she would become every bit as loyal as the most loyal of dogs. Pushinka's tale was only beginning. She and Lyudmila would live through much together, as would many of the other foxes and many of the other researchers working in Siberia, for this bold experiment in domestication was only just starting to reveal all the wonders it would serve up for science.

For more, see Lee Dugatkin and Lyudmila Trut's new book How To Tame a Fox {and Build A Dog}.

Excerpt modified from Lee Dugatkin and Lyudmila Trut's 2017 book How To Tame a Fox {and Build A Dog}, The University of Chicago Press

Belyaev's plan for the experiment was audacious. The domestication of a species was thought to happen gradually, over thousands of years. How could he expect any significant results, even if the experiment ran for decades? And yet, here was a fox like Pushinka, who was so much like a dog that she came when her name was called and could be let out on the farm without a leash. She followed the workers around as they did their chores, and she loved going for walks with Lyudmila along the quiet country road that ran by the farm on the outskirts of Novosibirsk, Siberia. And Pushinka was just one of the hundreds of foxes they had bred for tameness.

By moving into the house on the edge of the farm with Pushinka, Lyudmila was taking the fox experiment into unprecedented terrain. Their 15 years of genetic selection for tameness in the foxes had clearly paid off. Now, she and Belyaev wanted to discover whether by living with Lyudmila, Pushinka would develop the special bond with her that dogs have with their human companions. Except for house pets, most domesticated animals do not form close relationships with humans, and by far the most intense affection and loyalty forms between people and their dogs. What made the difference? Had that deep human-animal bond developed over a long time? Or might this affinity for people be a change that could emerge quickly, as with so many other changes Lyudmila and Belyaev had seen in the foxes already? Would living with a human come naturally to a fox that was so domesticated?

Lyudmila had chosen Pushinka to be her companion within moments of first setting eyes on her, when she was an adorable little three-week-old pup frolicking with her brothers and sisters. When Lyudmila looked into Pushinka's eyes, she felt an intense sense of connection, more than with any fox before. Pushinka also showed a remarkable enthusiasm for human contact. She would wag her tail furiously with excitement whenever Lyudmila or one of the farm workers came near her, whimpering with glee and looking up eagerly at them with an unmistakable request that they stop and pet her. No one could walk by her without doing so. Lyudmila had decided to move Pushinka into the house after she had turned one year old, mated, and was carrying a litter of pups. That way, Lyudmila would be able to observe not only how Pushinka adjusted to living with her, but whether pups born in the company of humans might socialize differently than other pups born on the farm. On March 28, 1975, ten days before she was due to deliver, Pushinka was taken to her new home.

Lyudmila had chosen Pushinka to be her companion within moments of first setting eyes on her, when she was an adorable little three-week-old pup frolicking with her brothers and sisters. When Lyudmila looked into Pushinka's eyes, she felt an intense sense of connection, more than with any fox before. Pushinka also showed a remarkable enthusiasm for human contact. She would wag her tail furiously with excitement whenever Lyudmila or one of the farm workers came near her, whimpering with glee and looking up eagerly at them with an unmistakable request that they stop and pet her. No one could walk by her without doing so. Lyudmila had decided to move Pushinka into the house after she had turned one year old, mated, and was carrying a litter of pups. That way, Lyudmila would be able to observe not only how Pushinka adjusted to living with her, but whether pups born in the company of humans might socialize differently than other pups born on the farm. On March 28, 1975, ten days before she was due to deliver, Pushinka was taken to her new home.The 700-square-foot house had three rooms in addition to a kitchen and bathroom. Lyudmila had moved a bed, a small couch, and a desk into one room to serve as her bedroom and office combined, and she had built a den in another room for Pushinka. The third room was used as a common area, furnished with a few chairs and a table, where Lyudmila ate her meals and where, on occasion, research assistants or other visitors could gather. Pushinka would be free to roam throughout.

When Pushinka arrived early in the morning of the first day, she began racing around the house, in and out of rooms, highly agitated. Normally, pregnant foxes so close to giving birth spend most of their time lying down in their dens, but Pushinka paced and paced from one room to the other. She'd scratch at the wood chips that lined her den floor and lie down briefly, but then she'd jump right back up again and make another circuit of the house. Though she was comfortable with Lyudmila and came over to her often for some petting, Pushinka was clearly unsettled. These strange new surroundings seemed to be causing her extreme anxiety. She wouldn't eat anything all day except for a small piece of cheese and an apple that Lyudmila had brought with her for her own snack. That afternoon, Lyudmila was joined by her daughter, Marina, and Marina's friend, Olga. The girls wanted to be there for Pushinka's big move-in day. At about 11:00 p.m., with Pushinka still pacing around the house, the three of them turned in for the night, the two girls lying down on the floor under blankets next to Lyudmila's bed. To their great surprise and Lyudmila's relief, as they began to drift off to sleep, Pushinka silently sneaked into their room and lay down right alongside the girls. Then, she, too, finally relaxed and went to sleep.

When Pushinka arrived early in the morning of the first day, she began racing around the house, in and out of rooms, highly agitated. Normally, pregnant foxes so close to giving birth spend most of their time lying down in their dens, but Pushinka paced and paced from one room to the other. She'd scratch at the wood chips that lined her den floor and lie down briefly, but then she'd jump right back up again and make another circuit of the house. Though she was comfortable with Lyudmila and came over to her often for some petting, Pushinka was clearly unsettled. These strange new surroundings seemed to be causing her extreme anxiety. She wouldn't eat anything all day except for a small piece of cheese and an apple that Lyudmila had brought with her for her own snack. That afternoon, Lyudmila was joined by her daughter, Marina, and Marina's friend, Olga. The girls wanted to be there for Pushinka's big move-in day. At about 11:00 p.m., with Pushinka still pacing around the house, the three of them turned in for the night, the two girls lying down on the floor under blankets next to Lyudmila's bed. To their great surprise and Lyudmila's relief, as they began to drift off to sleep, Pushinka silently sneaked into their room and lay down right alongside the girls. Then, she, too, finally relaxed and went to sleep.As Lyudmila would discover over the course of many months with Pushinka, the lovable little fox would not only become perfectly comfortable living with her, she would become every bit as loyal as the most loyal of dogs. Pushinka's tale was only beginning. She and Lyudmila would live through much together, as would many of the other foxes and many of the other researchers working in Siberia, for this bold experiment in domestication was only just starting to reveal all the wonders it would serve up for science.

For more, see Lee Dugatkin and Lyudmila Trut's new book How To Tame a Fox {and Build A Dog}.

Excerpt modified from Lee Dugatkin and Lyudmila Trut's 2017 book How To Tame a Fox {and Build A Dog}, The University of Chicago Press

by Lee Alan Dugatkin and Lyudmila Trut, published by the University of Chicago Press. © 2017 by Lee Alan Dugatkin and Lyudmila Trut.

In 1959, Dmitri Belyaev and Lyudmila Trut began what would come to be one of the longest-running experiments in biology. For the last 58 years they have been domesticating silver foxes and studying evolution in real time. But in 1952, seven years before this experiment began, Belyaev initiated a pilot study to determine whether or not his audacious ideas about domestication merited a full-fledged experiment. Here we tell that story.

One afternoon in the fall of 1952, thirty-five-year-old Dmitri Belyaev, clad in his signature dark suit and tie, boarded the overnight train from Moscow to Tallinn, the capital of Estonia on the coast of the Baltic Sea. Across the waters from Finland, but at the time, a world away, Tallinn was shrouded behind the Iron Curtain that divided eastern and western Europe after World War II. Belyaev was on his way to speak with a trusted colleague, Nina Sorokina, who was the chief breeder at one of the many fox farms he collaborated with in developing breeding techniques. Trained as a geneticist, Belyaev was a lead scientist at the government-run Central Research Laboratory on Fur Breeding Animals in Moscow, charged with helping breeders at the many commercial fox and mink farms run by the government to produce more beautiful and luxurious furs. He was hoping that Sorokina would agree to help him test a theory he had about how the domestication of animals had come about, one of the most beguiling open questions in animal evolution.

Belyaev carried with him several packs of cigarettes, a simple meal of hard-boiled eggs and hard salami, and a number of books and scientific papers. A voracious reader, he always traveled with a good novel or book of plays or poems, along with a number of science books and papers, on his many long train rides to the fox and mink farms scattered across the vast expanses of the Soviet Union. Even as he was intent to keep up with the rush of important new findings and theories in genetics and animal behavior pouring out of labs in Europe and the US, he always made time for his love of Russian literature. He was a particular enthusiast of works reflecting on the hardships endured by his countrymen through hundreds of years of political turmoil, works that were all too relevant to the upheavals Stalin had inflicted on the Soviet Union since his ascent to power decades earlier.

Dmitri’s taste in literature ranged from the cunning folktales of the country’s beloved storyteller, Nikolai Leskov, in which unschooled peasants often outwit their more learned superiors, to the mystical poetry of Alexander Blok, who wrote presciently shortly before the 1917 revolution that “a great event was coming.” One of his favorite works was the play Boris Godunov, by Russia’s great nineteenth-century poet and playwright Alexander Pushkin. A cautionary tale inspired by Shakespeare’s Henry plays, it recounts the tempestuous reign of the popular reformist tsar, who opened up trade with the West and instituted educational reform, but also dealt harshly with his enemies. Godunov’s sudden death from a stroke in 1605 ushered in the bloody era of civil war known as the Time of Troubles. That brutal period 350 years ago was mirrored in the terror and devastation Stalin had perpetuated as Dmitri was growing up in the 1930s and ’40s.

Stalin had also supported a brutal crackdown on work in genetics, and in 1952 it was still a very dangerous time to be a geneticist in Russia. Belyaev followed the new developments in the field at great risk to himself and his career. With Stalin’s backing, for more than a decade Trofim Lysenko, a charlatan who posed as a scientist, had wielded enormous influence over the Soviet scientific community, and one of his primary causes was a vehement crusade against genetics research. Many of the best researchers had been deposed from their positions, either thrown into prison camps or forced to resign and accept menial positions. Some had been killed, including Dmitri’s older brother, who was a leading light in the field. Before Lysenko’s rise to power, Russia was a world leader in genetics. A number of the best Western geneticists—such as American Herman Muller—had even made the long journey east for the chance to work with Soviet geneticists. Now Russian genetics was in a shambles, with any kind of serious research strictly prohibited.

But Dmitri was determined not to allow Lysenko and his thugs to keep him from conducting research. His work in fox and mink breeding had given him an idea about the great outstanding mystery of domestication, and it was simply too good for him not to find a way to test it.

The methods of breeding employed by our ancestors who domesticated the sheep, goats, pigs, and cows that were so vital to the development of civilization were well understood. Dmitri used them in his work every day at fox and mink farms. But the question of how domestication had gotten started in the first place had remained a riddle. The ancestors of domesticated animals, in their wild state, would likely have simply run away in fear or attacked if a human had approached. What happened to change this and make breeding them possible?

Belyaev thought he might have found the answer. Paleontologists had argued that the first animal to be domesticated was the dog, and by this time, evolutionary biologists were sure that dogs evolved from wolves. Dmitri had become fascinated by how an animal as naturally averse to human contact and as potentially aggressive as a wolf had evolved over tens of thousands of years into the lovable, loyal dog. His work breeding foxes had provided him an important clue, and he wanted to test the theory he was still in the early stages of developing. He thought he knew what had first set the process in motion.

Belyaev was traveling to Tallinn to ask Nina Sorokina to help him get started on a bold and unprecedented project—he wanted to mimic the evolution of the wolf into the dog. Because the fox is a close genetic cousin of the wolf, it seemed plausible to him that whatever genes were involved in the evolution of wolves into dogs were shared by the silver foxes raised on the farms all over the Soviet Union. As a lead scientist at the Central Research Laboratory on Fur Breeding Animals, he was in a perfect position to conduct the experiment he had in mind. Dmitri’s breeding work was of such importance to the Soviet government, because of the badly needed foreign currency that the sale of furs brought into the government’s coffers, that he believed as long as he explained the experiment as an effort to improve the production of furs, it could be run safely.

Even so, the fox domestication experiment he had in mind was sufficiently risky that it would have to be run far away from the prying eyes of Lysenko’s goons in Moscow. That’s why he had decided to ask Nina to help him get it started under the auspices of her breeding program at a fox farm in far away Tallin. Dmitri had collaborated with her on several successful projects to produce shinier and silkier furs, and he knew she was very talented. They had developed a good relationship, and he believed he could trust her and that she would trust him.

His plan for the experiment was on a scale never before carried out in genetic research, which worked primarily with tiny viruses and bacteria, or fast-breeding flies and mice, not animals like foxes, that mate only once a year. Due to the time it would take to breed each generation of fox pups, the experiment might take many years to produce results, perhaps even decades, or longer. But he felt launching it was worth both the long commitment and the risk. If it did produce results, they might well be groundbreaking.

Disembarking from his long train journey to Tallinn, Dmitri boarded a local bus heading south, traveling roads so bumpy they barely merited the name, through many tiny villages. His destination was the little hamlet of Kohila, buried deep in the Estonian forest. Not so much a village as a corporate outpost, Kohila was typical of the dozens of these industrial-scale fur farms scattered across the region. Spread out over 150 acres, the farm housed about 1500 silver foxes in dozens of rows of metal-roofed long wooden sheds, each of which contained dozens of cages. The workers and their families lived a ten-minute walk away from the farm in a bare-bones settlement of drab housing units, a small school, a few shops, and a couple of social clubs.

Nina Sorokina struck a somewhat incongruous figure against the dreary backdrop of this remote outpost. She was a beautiful, dark-haired woman, also in her mid-thirties, keenly intelligent and intense about her work, commanding a powerful position for a female in such a vital industry. A welcoming host, she enjoyed inviting Dmitri for tea in her office whenever he visited the farm. When he arrived after his long journey, they went right away to her office to talk in private. Over tea and cakes, with an ever-present cigarette dangling from his mouth, he told her what he was proposing—to domesticate the silver fox. She would not have been unreasonable to think her friend somewhat mad. Most of the foxes at the fur farms were so aggressive that when caretakers and breeders approached them, they bared their sharp canine teeth and lunged at them, snarling viciously. When foxes bite, they bite hard, and Nina and her team of breeders wore two-inch thick protective gloves that rode halfway up their forearms when they got anywhere near these animals. But Nina was intrigued, and she asked him why he wanted to attempt this.

Dmitri told Nina he had been fascinated by the unanswered questions about domestication, and that he was especially taken by the puzzle as to why domesticated animals could breed more than once a year, but their wild ancestors rarely did. If he could domesticate foxes, they might also be able to breed more often, which would be very good for business.

He didn’t want to put Nina at risk by explaining more. The full truth was that if the experiment worked, it might provide the answers to many important outstanding questions about domestication in all species. The more Belyaev had researched what was known about how animals had become domesticated, the more intrigued he had become by the mysteries about it, and those were mysteries that only an experiment of the kind he was proposing would be able to solve. How else could the answer to how domestication got started possibly be found? No written accounts of this first stage of the process were available. And though fossils of the early stages of domesticates such as dog-like wolves and early versions of domesticated horses had been found, they could reveal little about how the process got going in the first place. Even if remains could eventually be found that established what the first changes in animals’ physiology had been, that would not explain how and why they emerged.

A number of puzzles about domestication had not been solved. One was why so few animal species out of the millions on the planet had become domesticated—only a few dozen in all, mostly mammals, but also a few species of fish and birds, and a few insects, including the silk moth and the honeybee. Then there was the question why so many of the changes that had taken place in domesticated mammals were so similar. As Darwin, one of Dmitri’s intellectual idols, had noted, most of them developed patches of different coloring in their fur and on their hides—spots, patches, blazes, and other markings. Many also retained physical characteristics from childhood well into their adulthood that their wild cousins outgrew, such as floppy ears, curly tails, and babyish faces—referred to as the neotonic features, those that make young animals of so many species so adorable. Why would these characteristics have been selected for by breeders? Farmers raising cows, after all, had nothing to gain from their cows having black-and-white spotted hides. Why would pig farmers have cared whether their pigs had curly tails?

Belyaev thought the answer to all of the puzzling questions about domestication had to do with the essential defining characteristic of all domesticated animals—their tameness. He believed that the process of domestication was driven by our ancestors selecting animals according to this one key trait—that they were less aggressive and fearful toward humans than was typical for their species. This characteristic of tameness would have been the essential requirement for working with the animals in order to breed them for other desirable traits. Humans needed their cows, horses, goats, sheep, pigs, dogs, and cats to be nice and gentle toward their masters, regardless of what they were trying to get from them¾milk, meat, protection, or companionship. It wouldn’t do to be trampled by their food or maimed by their protectors.

Belyaev explained to Nina that in his work in fox and mink breeding he had noted that while most of the minks and foxes on the fur farms were either quite aggressive or were nervous and fearful towards people, a few were quite calm when people approached them. They weren’t bred to be calm, so the quality must have been part of the natural behavioral variation in a population. This, he posited, would have been true for the ancestors of all domesticates. And over evolutionary time, as our early ancestors had begun raising them and selecting for this innate tameness, the animals became more and more docile. He thought that all of the other changes involved in domestication had been triggered by this change in the behavioral selection pressure for tameness. Rather than either avoidance of humans or aggression towards them giving them the survival advantage, now being calm around humans gave them the edge. The animals living in human contact had more reliable access to food and were better protected from predators. He wasn’t sure yet how selection for tameness would have caused all the other genetic changes that we have see in domesticated animals (curly tails, longer reproductive periods, juvenile facial and body characteristics, and so on), but he had conceived of an experiment that he hoped would eventually provide the answer.

Nina was all ears. She had also observed that some foxes, though very few, were quite calm when approached, and she was intrigued by his theory. Belyaev explained the procedure he wanted Nina and her breeding team to follow. Every year, they should choose a few of the calmest foxes at Kohila at the breeding time in late January and mate them with one another. From the pups that those select foxes produced, they should again choose the calmest ones and breed them. The change from generation to generation might be subtle, he noted, even difficult to identify at first glance, but they should just use their best judgment. Perhaps, he suggested, this method would eventually lead to calmer and calmer foxes, the first step in domestication.

Dmitri suggested that Nina and her breeders assess calmness by observing closely how the foxes responded when they approached their cages or put their hands up in front of them. They might even try putting a sturdy stick slowly through the bars of the cage to see whether the foxes attacked it or held back. But he would leave it up to them to work out their methods; he was confident in Nina’s judgment. Nina, in return, had faith that Dmitri’s idea was worth pursuing.

But before she agreed, he wanted to discuss the risks. He knew Nina understood the danger of conducting an experiment in the genetics of domestication under Lysenko, but he nonetheless emphasized to her that she must carefully consider the issue. He told her it was probably a good idea not to mention the work to others, except her team, and he offered his suggestion that if she were asked about what they were doing, she could say that the purpose of the experiment was simply to see if they could increase fur quality and the number of pups born each year, which were acceptable areas of research to Lysenko.

Without a moment’s pause, Nina told him she would help him. She and her team would begin right away.

Nina decided they would always approach the foxes slowly and would also open each cage slowly and reach into it slowly with some food held in the gloved hand. When they did, some of the foxes lunged at them. Most of them backed away and snarled and sneered menacingly. But about a dozen out of the hundred or so they tested each year were slightly less agitated. They certainly weren’t calm, but they weren’t highly reactive and aggressive either. A few would even take the food offered from the workers’ hands. These foxes that didn’t bite the hands that fed them became the parents of the next generation in Dmitri and Nina’s pilot work.

Within three breeding seasons, Nina and her team were seeing some intriguing results. Some of the pups of the foxes they’d selected were a little calmer than their parents, grandparents, and great-grandparents. They would still sneer and react aggressively sometimes when their keepers approached them, but at other times, they seemed almost indifferent.

Belyaev was delighted. The changes in behavior were subtle, and in only a handful of foxes, but they had occurred in much less time than he had expected, a blink of time on the time scale of evolution. He was now intent on expanding the pilot program into a large-scale experiment.

For much more on the remarkable silver fox experiment from 1959- present, see: How to Tame a Fox {and Build a Dog} by Lee Dugatkin and Lyudmila Trut (2017, University of Chicago Press).

Published On: May 8, 2017

Lee Alan Dugatkin

Lee Alan Dugatkin is a Professor of Biology and Distinguished University Scholar in the Department of Biology at the University of Louisville. He is a behavioral ecologist and historian of science and his main area of research interest is the evolution of social behavior. Lee has spoken at more than 100 universities worldwide and is the author 0f 150+ articles on evolution and behavior. He is a frequent contributor to Scientific American, Psychology Today and the New Scientist. He is the author of numerous books, including Cooperation Among Animals: An Evolutionary Perspective (Oxford University Press, 1997), The Altruism Equation: Seven Scientists Search for the Origins of Goodness (Princeton University Press, 2006), and Mr. Jefferson and the Giant Moose (University of Chicago Press, 2009). Lee is also author of two textbooks: 1) Principles of Animal Behavior (W.W. Norton, 3rd edition, 2013) and 2) Evolution (W.W. Norton, 2012, coauthored with Carl Bergstrom).

Lyudmila Trut

Lyudmila N. Trut is head of the research group at the Institute of Cytology and Genetics of the Siberian Department of the Russian Academy of Sciences, in Novosibirsk. She received her doctoral degree in 1980. Her current research interests are the patterns of evolutionary transformations at the early steps of animal domestication. Her research group is developing the problem of domestication as an evolutionary event with the use of experimental models, including the silver fox, the American mink, the river otter and the wild gray rat.