First transgender athlete to medal at Olympics wins gold

There's a record number of openly LGBTQ athletes at the Tokyo Olympic Games.

By Siobhan Neela-Stock on August 6, 2021

Quinn is the first trans athlete to medal at the Olympics. Credit: OMar Vega / Getty Images

The first transgender athlete won Olympic gold on Thursday, marking a historic achievement, but one that's also bittersweet.

Quinn, along with the Canadian soccer team, played a long match against Sweden, with a tied result moving into a tense penalty shootout, which Canada won. More openly trans and non-binary athletes have competed in the Tokyo Olympic Games than ever before as intense debates over trans people in athletics have frustratingly swept through schools and statehouses in the U.S.

Quinn's the first openly trans athlete to participate in the Olympics after the International Olympic Committee changed its rules in 2004 to allow transgender athletes to compete in the Games. But they were followed by others competing in weightlifting and BMX racing later on in the Games.

Quinn's one of at least 181 openly queer athletes at the Tokyo Games, more than three times the number who participated in the Rio Games, according to Outsports.

Gold medallists Canada after the Tokyo 2020 Olympic Games women's final football match. Credit: TIZIANA FABI / AFP Via Getty Images

Although Quinn's said they're proud to see their name on the soccer roster, they're also sad past Olympians like them couldn't be open about their identities, Quinn revealed on Instagram a day before the Tokyo Olympics began. "I feel proud seeing 'Quinn' up on the lineup and on my accreditation. I feel sad knowing there were Olympians before me unable to live their truth because of the world," they wrote.

Quinn competed in the 2016 Rio Olympic Games, where they and their team won a bronze medal, but they weren't out yet.

In a September 2020 Instagram post, Quinn told the world they were trans. While they've been out with their loved ones for years, part of Quinn's motivation to come out online is to support queer people who may not see people like themselves on social media.

"Instagram is a weird space. I wanted to encapsulate the feelings I had towards my trans identity in one post but that’s really not why anyone is on here, including myself," Quinn wrote. "So instead I want to be visible to queer folks who don’t see people like them on their feed. I know it saved my life years ago."

Quinn's accomplishment comes as trans and nonbinary athletes, like Olympic weightlifter Laurel Hubbard and Olympic skateboarder Alana Smith, respectively, gain more mainstream recognition because of their presence in the Games.

SEE ALSO: 3 helpful tips for when you plan to come out online

Despite gains for trans athletes on the Olympic stage, conservatives in the U.S. continue to pass bills to stop trans teens from playing on sports teams that align with their gender.

"When trans kids have access to gender-affirming spaces at school, like a locker room, a restroom, a sports team, they are 25 percent less likely to commit suicide," Annie Lieberman, director of policy programs for Athlete Ally, an LGBTQ athletic advocacy nonprofit, told ABC News.

The hurdles transgender athletes face to play on the teams that make them feel the safest makes Quinn's gold medal in the Olympics all the more impactful.

CBC/Radio-Canada

Bleary-eyed fans across the country watched nervously as the Canadian women's soccer team took the field against Sweden in a closely contested Olympic gold-medal match early Friday morning, but Georgia Simmerling was remarkably calm.

"To be honest, I'm pretty chill about it," said Simmerling, whose partner, Stephanie Labbé, is the starting goalkeeper for Canada.

"I know her so well, so if she gets hit or knocked down, I'm just sending her good vibes. I know she'll get back up."

Simmerling, an Olympian herself who just got back from competing at the Tokyo Games in track cycling, has experience steeling herself and steadying her emotions before a big competition.

"I guess I know how to control my nerves," she said.

"I obviously enjoy it. I love it. I'm her biggest fan. But yeah, I stay pretty calm."

Surrounded by fans gathered early Friday at a Calgary bar — eager to see the Canadian soccer team take its first crack at an Olympic gold medal, after earning bronze in their past two efforts — Simmerling said she was confident in Labbé.

"Steph turns into a bit of beast when it comes to stepping onto that field," she said.

That proved to be prescient.

After giving up a first-half goal, the Canadian team came from behind to tie the game and then endured numerous, dangerous-looking Swedish attacks in extra time, but ultimately emerged victorious in a six-round penalty shootout.

Both teams put on an outstanding display of goalkeeping in the shootout, but Labbé was just that much better than her Swedish counterpart, preventing four of Sweden's six attempts.

In the sixth and decisive round, Labbé denied Jonna Andersson's attempt and then Julia Grosso delivered the dagger for Canada by a matter of centimetres.

The Swedish keeper guessed correctly where Grosso would shoot and got a hand on the ball — looking for a fraction of a second like she had saved it — but it deflected off her glove and up into the top of the netting.

There may have been no crowd at the stadium in Japan, but the fans at the Calgary bar erupted in cheers, hugs and high-fives.

As the pandemonium calmed, Simmerling caught her breath and considered the magnitude of what Labbé and her teammates had just accomplished.

"These girls are meant to do this," she said.

"They know what they need to do and they came up big. That was unbelievable. It was so incredible to watch."

Nesthy Petecio fell short in a close gold medal bout, but etched her name in Filipino Olympic history with her silver medal

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/69671679/1332063486.0.jpg)

Tokyo Olympics 2020: 'About time', LGBTQ athletes unleash rainbow wave at Games

A wave of rainbow-colored pride, openness and acceptance is sweeping through Olympic pools, skateparks, halls and fields, with a record number of openly gay competitors in Tokyo.

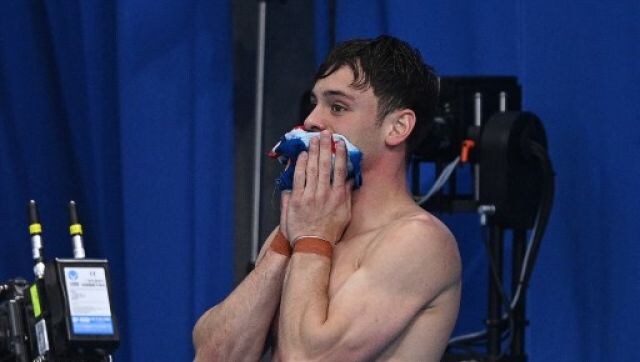

“I hope that any young LGBT person out there can see that no matter how alone you feel right now you are not alone," Tom Daley said. AFP

When Olympic diver Tom Daley announced in 2013 that he was dating a man and “couldn't be happier,” his coming out was an act of courage that, with its rarity, also exposed how the top echelons of sport weren't seen as a safe space by the vast majority of LGBTQ athletes.

Back then, the number of gay Olympians who felt able and willing to speak openly about their private lives could be counted on a few hands. There'd been just two dozen openly gay Olympians among the more than 10,000 who competed at the 2012 London Games, a reflection of how unrepresentative and anachronistic top-tier sports were just a decade ago and, to a large extent, still are.

Still, at the Tokyo Games, the picture is changing.

A wave of rainbow-colored pride, openness and acceptance is sweeping through Olympic pools, skateparks, halls and fields, with a record number of openly gay competitors in Tokyo. Whereas LGBTQ invisibility used to make Olympic sports seem out of step with the times, Tokyo is shaping up as a watershed for the community and for the Games — now, finally, starting to better reflect human diversity.

“It's about time that everyone was able to be who they are and celebrated for it,” said US skateboarder Alexis Sablone, one of at least five openly LGBTQ athletes in that sport making their Olympic debut in Tokyo.

“It's really cool,” Sablone said. “What I hope that means is that even outside of sports, kids are raised not just under the assumption that they are heterosexual."

The gay website Outsports.com has been tallying the number of publicly out gay, lesbian, bisexual, transgender, queer and nonbinary athletes in Tokyo. After several updates, its count is now up to 168, including some who petitioned to get on the list. That's three times the number that Outsports tallied at the last Olympics in Rio de Janeiro in 2016. At the London Games, it counted just 23.

“The massive increase in the number of out athletes reflects the growing acceptance of LGBTQ people in sports and society,” Outsports says.

Daley is also broadcasting that message from Tokyo, his fourth Olympics overall and second since he came out.

After winning gold for Britain with Matty Lee in 10-metre synchronised diving, the 27-year-old reflected on his journey from young misfit who felt “alone and different" to Olympic champion who says he now feels less pressure to perform because he knows that his husband and their son love him regardless.

“I hope that any young LGBT person out there can see that no matter how alone you feel right now you are not alone," Daley said. "You can achieve anything, and there is a whole lot of your chosen family out here."

“I feel incredibly proud to say that I am a gay man and also an Olympic champion,” he added. “Because, you know, when I was younger I thought I was never going to be anything or achieve anything because of who I was.”

Still, there's progress yet to be made.

Among the more than 11,000 athletes competing in Tokyo, there will be others who still feel held back, unable to come out and be themselves. Outsports’ list has few men, reflecting their lack of representation that extends beyond Olympic sports. Finnish Olympian Ari-Pekka Liukkonen is one of the rare openly gay men in his sport, swimming.

“Swimming, it’s still much harder to come out (for) some reason," he said. "If you need to hide what you are, it’s very hard.”

Only this June did an active player in the NFL — Las Vegas Raiders defensive end Carl Nassib — come out as gay. And only last week did a first player signed to an NHL contract likewise make that milestone announcement. Luke Prokop, a 19-year-old Canadian with the Nashville Predators, now has 189,000 likes for his “I am proud to publicly tell everyone that I am gay" post on Twitter.

The feeling that “there's still a lot of fight to be done” and that she needed to stand up and be counted in Tokyo is why Elissa Alarie, competing in rugby, contacted Outsports to get herself named on its list. With their permission, she also added three of her Canadian teammates.

“It’s important to be on that list because we are in 2021 and there are still, like, firsts happening. We see them in the men’s professional sports, NFL, and a bunch of other sports," Alarie said. "Yes, we have come a long way. But the fact that we still have firsts happening means that we need to still work on this.”

Tokyo's out Olympians are also almost exclusively from Europe, North and South America, and Australia/New Zealand. The only Asians on the Outsports list are Indian sprinter Dutee Chand and skateboarder Margielyn Didal from the Philippines.

That loud silence resonates with Alarie. Growing up in a small town in Quebec, she had no gay role models and "just thought something was wrong with me.”

"To this day, who we are is still illegal in many countries," she said. “So until it's safe for people in those countries to come out, I think we need to keep those voices loud and clear."

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/22757984/1332060807.jpg)