Ed Browne

Scientists have discovered a fossil that once belonged to a previously unknown type of four-legged whale that lived tens of millions of years ago.

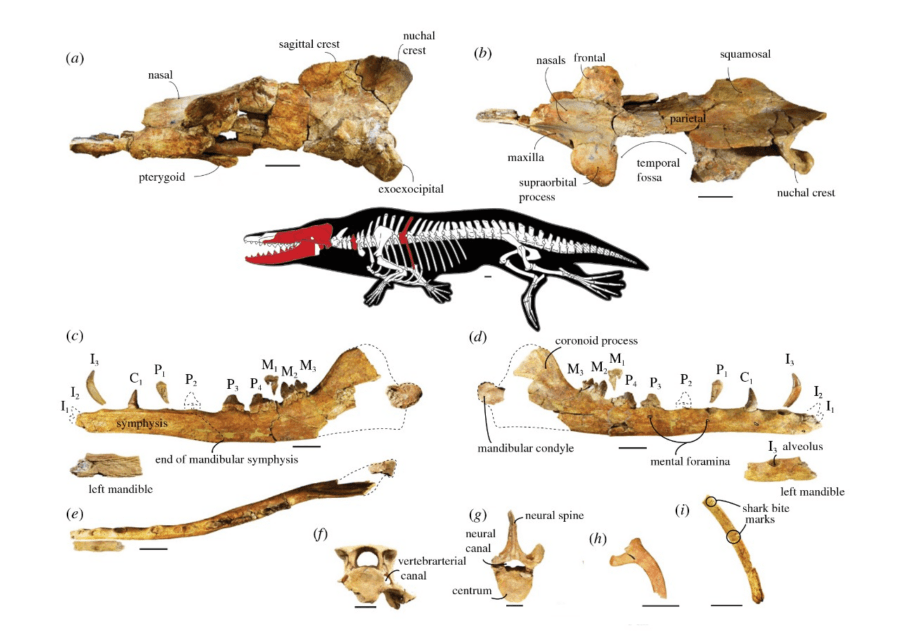

The researchers also found that the whale's mouth was better-designed for a "strong raptorial feeding style" than was usual for other types of early whale-like animals and that it would have been a fearsome predator.

The evolution of whales is thought to have proceeded at a rapid pace millions of years ago—so fast that over a period of 10 million years the ancestors of whales evolved from "deer-like" herbivores that lived on land into carnivorous marine animals, according to the researchers' study published in the Proceedings Of The Royal Society B.

The fossil that the team have investigated is thought to have come from a protocetid, a type of early whale from the Eocene era which started 56 million years ago and ended 33.9 million years ago.

The researchers have named the newly discovered extinct whale species Phiomicetus anubis. The first part of the name refers to the Fayum Depression in Egypt's Western Desert where the fossil was found, and the second part refers to Anubis, the ancient Egyptian god of the afterlife.

The fossil is 43 million years old. In a press release documenting the team's work, lead author Abdullah Gohar at Mansoura University in Egypt called it "a critical discovery for Egyptian and African paleontology."

The animal, estimated to have had a body length of about 10 feet and a body mass of about 1,320 lb, would likely have been a top predator in its community at the time, like the killer whale of today.

There is still much to be learned about early whale evolution in Africa and researchers hope that studying the region could uncover more about how early whales changed from animals that spent time both in and out of the water to animals that lived in the water all the time.

The fact that the early whale ancestors walked on four legs is nothing new. Indeed, scientists think that a four-legged goat-sized animal known as Pakicetus was one of the first cetaceans—the family of marine animals including dolphins and whales—ever to exist.

But it is the evolutionary pathway from these four-legged ancestors to the fully water-based animals we know today that intrigues researchers, according to an article on four-legged whales by the the U.K.'s National History Museum.

Other aspects of Phiomicetus anubis that set it apart from other protocetids include an elongated temporal fossae, or shallow depression on the side of the skull, and a difference in the placement of the pterygoid bones.

The study abstract concludes: "The discovery of Phiomicetus further augments our understanding of the biogeography and feeding ecology of early whales."

By Kaleena Fraga | Checked By Erik Hawkins

Published August 26, 2021

Forty-three million years ago, the fearsome four-legged whale stalked prey both underwater and on land.

The four-legged whale called Phiomicetus anubis used its powerful jaws to kill prey.

Ancient monsters once roamed the Earth. Paleontologists in Egypt just came across one such creature, a four-legged whale so fearsome that they named it Phiomicetus anubis, after the Egyptian god of death.

“It was a successful, active predator,” said Abdullah Gohar. A graduate student at the Mansoura University Vertebrate Palaeontology Centre, Gohar is the lead author of a recent paper describing the discovery.

“I think it was the god of death for most animals that lived alongside it.”

In a nod to the whale’s jackal-like head and ability to kill, paleontologists called it Phiomicetus anubis. Anubis, of course, was the Egyptian god of death. Phiomicetus categorizes the whale with other similar fossils, which straddle the species’ transition from land to sea.

“Phiomicetus anubis is a key new whale species, and a critical discovery for Egyptian and African paleontology,” explained Gohar.

Paleontologists found a number of the whale’s bones in an area of Egypt famous for sea life fossils.

A team of paleontologists first came across Phiomicetus anubis in 2008. Then, while searching through Egypt’s Fayum Depression — an area teeming with sea life fossils — they found remnants of the 43-million-year-old monster in middle Eocene rocks.

With a body length of almost 10 feet and weighing close to 1,300 pounds, paleontologists are confident that the four-legged whale once dominated the animal kingdom.

“We discovered how [its] fierce, deadly, and powerful jaws were capable of tearing a wide range of prey,” Gohar said. His study called the whale’s feeding style “raptorial.”

The study went on to describe how the whale used its incisor and canine teeth to “catch, debilitate and retain faster and more elusive prey items (e.g. fish) before they were moved to the cheek teeth to be chewed into smaller pieces and swallowed.”

As the four-legged whale stalked prey — both on land and underwater — it also likely caught and killed crocodiles and calves of other whale species.

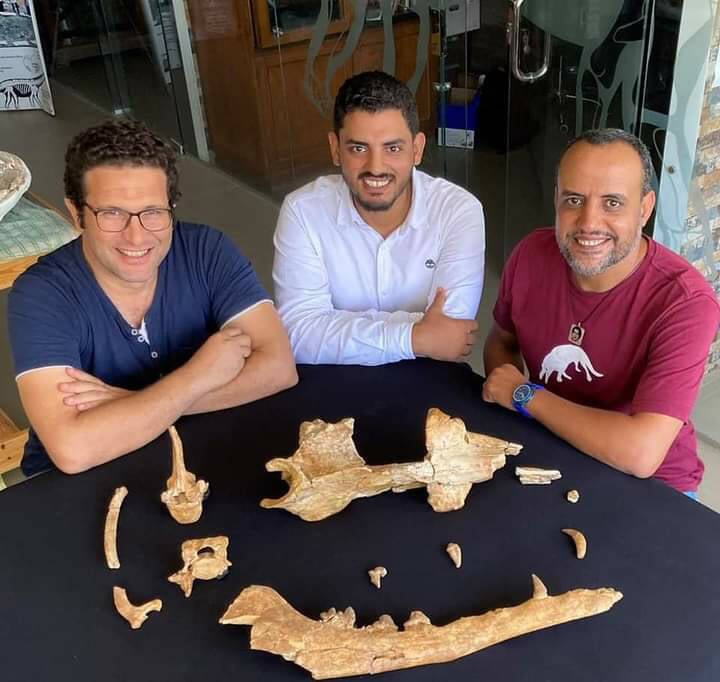

Abdullah Gohar, center, with bones from Phiomicetus anubis.

The discovery of the four-legged whale is an exciting moment for more reasons than one. For starters, not much is known about ancient whales’ transition from land to sea. Though today’s whales are strictly aquatic, their ancient ancestors were amphibious.

The earliest known whale, Pakicetus attocki, lived in the shallow ocean near present-day Pakistan some 50 million years ago. Like Phiomicetus anubis, it had four legs.

However, paleontologists have much to learn about how ancient whales spread across the world.

“This fossil really starts to give us a sense of when whales moved out of the Indo-Pakistan ocean region and started dispersing across the world,” noted Jonathan Geisler, an associate professor of anatomy at the New York Institute of Technology.

But the discovery of the four-legged whale is significant for another reason. It marks the first time that an Arab team discovered, described, and named a whale fossil.

“This paper represents a breakthrough for Arab paleontologists,” Goher said.

“This science remained the preserve of foreign scientists for a long period of time, despite the richness of the Egyptian natural heritage with important fossils of the ancestors of whales.”

For now, paleontologists like Gosar will continue to explore the Fayum Depression. They hope to better understand how ancient whales evolved and moved around the world.

And the Fayum Depression certainly holds more keys to the past. Once, the sea covered this swath of the Egyptian desert. But now, its million-year-old rocks — rich with fossils — are exposed to the sun.

Posted Wed 25 Aug 2021

Scientists have discovered a 43-million-year-old fossil of a previously unknown amphibious four-legged whale species in Egypt.

Key points:

The fossil was unearthed from middle Eocene rocks in the Fayum Depression in Egypt's Western Desert

The new whale was about 3m long and weighed about about 600kg

It has been named Phiomicetus anubis, after the Egyptian god of death

The newly discovered whale belongs to the Protocetidae, a group of extinct whales that falls in the middle of their transition from land to sea, the Egyptian-led team of researchers said in a statement.

Its fossil was unearthed from middle Eocene rocks in the Fayum Depression in Egypt's Western Desert — an area once covered by sea that has provided a rich seam of discoveries showing the evolution of whales — before being studied at Mansoura University Vertebrate Palaeontology Centre (MUVP).

The new whale, named Phiomicetus anubis, had an estimated body length of about 3 metres and a body mass of about 600kg, and was likely a top predator, the researchers said.

Its partial skeleton revealed it as the most primitive protocetid whale known from Africa.

"Phiomicetus anubis is a key new whale species, and a critical discovery for Egyptian and African paleontology," said Abdullah Gohar of MUVP, lead author of a paper on the discovery published in the journal Proceedings of the Royal Society B.

"It was a successful, active predator," Mr Gohar told Live Science. "I think it was the god of death for most animals that lived alongside it."

The whale's genus name honours the Fayum Depression, and its species name refers to Anubis, the ancient Egyptian canine-headed god associated with mummification and the afterlife.

Despite recent fossil discoveries, the big picture of early whale evolution in Africa has largely remained a mystery, the researchers said.

Work in the region had the potential to reveal new details about the evolutionary transition of whales from being amphibious to fully aquatic.

The father of #Phiomicetus, @Gohar_A_S hanging his new publication on #Sallam_Lab’ wall of honor!!!! pic.twitter.com/3DmMCVBgva— Hesham Sallam (@heshamsallam) August 25, 2021

With rocks covering about 12 million years, discoveries in the Fayum Depression "range from semi-aquatic crocodile-like whales to giant fully aquatic whales", said Mohamed Sameh of the Egyptian Environmental Affairs Agency, a co-author.

The new whale has raised questions about ancient ecosystems and pointed research towards questions such as the origin and coexistence of ancient whales in Egypt, said Hesham Sellam, founder of the MUVP and another co-author.

Reuters

James Rollins

She stood, surrounded by ice, but the back half of the chamber was solid rock. A bowl of stone encompassed the far wall and overhung the ceiling.

Something touched her elbow, startling her. It was only Dr. Ogden. He drew her eyes back to him, his lips moving.

“It’s the remnant of an ancient cliff face. At least according to MacFerran,” Henry said, naming the head of the geology team. “He says it must have broken from the landmass as the glacier calved and formed this ice island. It dates back to the last ice age. He immediately wanted to blast away sections and core out samples, but I had to stop him.”

Amanda was still too stunned to speak.

“On just cursory examination, I found dead lichen and frozen mosses. Searching the cliff pockets more thoroughly, I discovered three bird’s nests, one with eggs!” He began to speak more rapidly with his excitement. Amanda had to concentrate on his lips. “There were also a pack of rodents and a snake trapped in ice. It’s a treasure trove of life from that age, a whole frozen biosphere.” He led the way across the cavern toward the stone wall. “But that’s not all! Come see!”

She followed, staring ahead. The wall was not as solid as it had first appeared. It was pocked with cubbies and alcoves. Some sections seemed broken and half tumbled out. Deep clefts also delved into the rock face, but they were too dark to discern how far they penetrated.

Amanda crossed under the arch of stone and eyed with trepidation the slabs precariously balanced overhead. None of it seemed as solid as it had been a moment ago.

Dr. Ogden grabbed her elbow, squeezing hard, stopping her. “Careful,” he said, drawing her eye, then pointing to the floor.

A few steps ahead lay an open well in the ice-rink floor. It was too perfectly oval to be natural, and the edges were scored coarsely.

“They dug one of them out from here.”

Amanda frowned. “One of what?” She spotted other pits in the ice now.

Henry tugged her to the side. “Over here.” He slipped a canteen of water from his belt. He motioned her down on a knee on the ice. They were now only a few yards from the shattered stone cliff. Hunched down, it was almost like they were on a frozen lake with the shore only a few steps away.

The biologist whisked the ice with his gloved hand. Then placed his flashlight facedown onto the frozen lake. Lit from on top, the section of ice under them glowed. But details were murky because of the frost on the ice’s surface. Still, Amanda could make out the dark shadow of something a few feet under the ice.

Henry sat back and opened his canteen. “Watch,” he mouthed to her.

Leaning over, he poured a wash of water over the surface, melting the frost rime and turning the ice to glass under them. The light shone clearly, limning what lay below in perfect detail.

Amanda gasped, leaning away.

The creature looked as if it were lunging up through the ice at her, caught for a moment in a camera’s flash. Its body was pale white and smooth-skinned, like the beluga whales that frequented the Arctic, and almost their same size, half a ton at least. But unlike the beluga, this creature bore short forelimbs that ended in raking claws and large webbed hind limbs, spread now, ready to sweep upward at her. Its body also seemed more supple than a whale’s, with a longer torso, curving like an otter. It looked built for speed.

But it was the elongated maw, stretched wide to strike, lined by daggered teeth, that chilled her to the bone. It gaped wide enough to swallow a whole pig. Its black eyes were half rolled to white, like a great white lunging after prey.

Amanda sat back and took a few puffs from her air warmer as her limbs tremored from the cold and shock. “What the hell is it?”

The biologist ignored her question. “There are more specimens!” He slid on his knees across the ice and revealed another of the creatures lurking just at the cliff face. This beast was curled in the ice as if in slumber, its body wrapped in a tight spiral, jaws tucked in the center, tail around the whole, not unlike a dog in slumber.

Henry quickly gained his feet. “That’s not all.”

Before she could ask a question, he crossed and entered a wide cleft in the rock face. Amanda followed, chasing after the light, still picturing the jaws of the monster, wide and hungry.

The cleft cut a few yards into the rock face and ended at a cave the size of a two-car garage.

Amanda straightened. Positioned against the back wall were six giant ice blocks. Inside each were frozen examples of the creatures, all curled in the fetal-like position. But it was the sight in the chamber’s center that had Amanda falling back toward the exit.

Like a frog in a biology lab, one of the creatures lay stretched across the ice floor, legs staked spread-eagle. Its torso was cut from throat to pelvis, skin splayed back and pinned to the ice. From the frozen state of the dissection, it was clearly an old project. But she caught only a glimpse of bone and organs and had to turn away.

She hurried back out onto the open frozen lake. Dr. Ogden followed. He seemed oblivious to her shock. He touched her arm to draw her eyes.

“A discovery of this magnitude will change the face of biology,” Henry said, bending close to her in his insistence. “Now you can see why I had to stop the geologists from ruining this preserved ecosystem. A find like this…preserved like this—”

Amanda cut him off. Her voice brittle. “What the hell are those things?”

Henry blinked at her and waved a hand. “Oh, of course. You’re an engineer.”

Though she was deaf, she could almost hear his condescension. She rankled a bit, but held her tongue.

He motioned back to the cleft and spoke more slowly. “I studied the specimen back there all day. I have a background in paleobiology. Fossilized remains of such a species have been discovered in Pakistan and in China, but never such a preserved specimen.”

“A specimen of what, Henry?” Her eyes were hard on the biologist.

“Of Ambulocetus natans. What is commonly called ‘the walking whale.’ It is the evolutionary link between land-dwelling mammals and the modern whale.”

She simply gaped at him as he continued.

“It is estimated to have existed some forty-nine million years ago, then died out some thirty-six million years ago. But the splayed out legs, the pelvis fused into the backbone, the nasal drift…all clearly mark this as distinctly Ambulocetus.”

Amanda shook her head. “You can’t be claiming that these specimens are so old. Forty million years?

“No.” His eyes widened. “That’s just it! MacFerran says the ice at this level is only fifty thousand years old, dating back to the last ice age. And these specimens bear some unique features. My initial supposition is that some pod of Ambulocetus whales must have migrated to the Arctic regions, like modern whales do today. Once here, they developed Arctic adaptations. The white skin, the gigantism, the thicker layer of fat. Similar to the polar bear or beluga whales.”

Amanda remembered her own earlier comparison to the beluga. “And these creatures somehow survived up here until the last ice age? Without any evidence ever being discovered?”

“Is it really so surprising? Anything that lived and died on the polar ice cap would have simply sunk to the bottom of the Arctic Ocean, a region barely glimpsed at all. And on land, permafrost makes it nearly impossible to carry out digs above the Arctic Circle. So it is entirely possible for something to have existed for eons, then died out without leaving a trace. Even today we have barely any paleological record of this region.”

Amanda shook her head, but she could not dismiss what she had seen. And she couldn’t discount his argument. Only in the past decade, with the advent of modern technology and tools, was the Arctic region truly being explored. Her own team back at Omega was defining a new species every week. So far, the discoveries were just new, unclassified phytoplankton or algae, nothing on the level of these creatures.

Henry continued, “The Russians must have discovered these creatures when they dug out their base. Or maybe t hey built the base here because of them. Who knows?”

Amanda remembered Henry’s early claim: It’s the reason the station was built here. “What makes you think that?” She flashed back again to the discovery on Level Four. This new discovery, amazing as it was, seemed in no way connected to the other.

Henry eyed her. “Isn’t it obvious?”

Amanda scrunched her brow.

“Ambulocetus fossils were only discovered in the past few years.” He pointed back to the cleft. “Back in World War Two, they knew nothing about them. So, of course, the Russians would come up with their own name for such a monster.”

Her eyes grew wide.

“They named their base after the creature,” Dr. Ogden explained needlessly. “A mascot of sorts, I imagine.”

Amanda stared down at the frozen lake, at the beast lunging up at her. She now knew what she was truly seeing. The monster of Nordic legend.

Grendel.

Ice Hunt - James Rollins

James Rollins invokes the polar environment so vividly you can hear the wind shriek and feel the ice forming on your nose, and the scientific/medical puzzles at the story's heart may remind you of Michael Crichton's best. The characters, while mostly familiar hero or villain types, are crisply drawn and in some cases quite sympathetic, but it's ...