By Ben Burgis

UAW president Shawn Fain’s speech was the best part of the DNC. It featured a direct focus on workers otherwise absent from party rhetoric, and sidestepped the culture wars to identify the “one true enemy” of corporate power.

The most shameful moment at this year’s Democratic National Convention (DNC) came on Tuesday night. Political commentator and The View cohost Ana Navarro, whose father was part of the Contra death squads secretly funded by the Ronald Reagan administration, euphemistically portrayed her family having to leave Nicaragua as “fleeing communism” and got applause for comparing Donald Trump to “the communists.”

That was jaw-dropping. But most of the other bad moments were more predictable. Uncommitted delegates were frozen out of meaningful participation. Venture capitalist and former American Express CEO Ken Chenault was invited to talk about how saving democratic institutions from Trump is important because those institutions create such a favorable business environment. Illinois governor J. B. Pritzker, in an otherwise supremely forgettable speech, jabbed Trump for not being a “real” billionaire like himself. Barack Obama’s speech was a reminder of exactly why his brand of liberalism was so thoroughly mediocre. And the less said about Hillary Clinton, the better.

The Democratic Party is a mess of contradictory forces that would be in different parties in any normal parliamentary democracy. Consequently, there were good moments too. Bernie Sanders was great as usual, showing off once again that he has the tightest message discipline in contemporary American politics. Every time he opens his mouth, he talks about wages and inequality and health care. And much of Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez’s speech was good, even if it was marred by her spurious claim that Kamala Harris is “tirelessly working” to achieve a cease-fire in Gaza. On Wednesday night, the proportion of January 6 relitigation to even remotely populist policy was dismal, although Walz’s speech at the end of the night made up for that to some extent.

But the brightest spot in the whole lineup was Shawn Fain of the United Auto Workers (UAW). He knocked it out of the park. He used the occasion to talk about strikes that have forced companies to reverse outsourcing. His speech even put a particular company, Stellantis, in the hot seat: on the day of the speech, UAW locals filed multiple grievances against the auto manufacturer, laying the groundwork for a grievance strike.

Fain said that workers can’t let the Right use culture-war distractions to divide them up because their “one true enemy” is the insatiable greed of corporate America. He hammered Trump not for being crass or “extremist” or a threat to the norms of American politics but for being a strikebreaker.

Amid what seems to be a regressive climate regarding class politics, Fain’s speech at the DNC — and his outspoken presence in general this past year — was a massive gust of fresh air.

Fain is the first directly elected president of the UAW. He was part of a reform caucus that opposed union corruption and damaging concessions to the bosses around issues like two-tiered pay structures. “Record profits,” he kept insisting, should generate “record contracts.”

Soon after Fain took the helm, he led his members out on an ambitious “stand-up strike.” It was the first time in the entire history of the union that the UAW had gone on strike against all three of the Big Three car manufacturers at the same time, and they won. Several months later, the UAW made history with a successful organizing drive at the Volkswagen plant in Chattanooga, Tennessee — a region and an employer that were, in combination, long thought to be impervious to unionization.

Fain’s approach often disturbs guardians of the economic status quo. In a profile for the New York Times, for example, he said that billionaires “don’t have a right to exist.” The idea of moving toward a society egalitarian enough not to support such obscene concentrations of wealth has long been unthinkable in mainstream American discourse, and Fain’s rhetoric has been enough to inspire CNBC’s Jim Cramer to babble hysterically about “class warfare” and even to compare Fain to Communist Party USA leader Earl Browder.

In real life, class warfare is inevitable given the basic structure of a capitalist economy. Business owners and workers have opposing interests, with the former always looking for new ways to use their power to squeeze more profits from the latter. The only question is whether this warfare will be one-sided. And on that issue, Fain’s simple message on Monday night at the DNC was that it doesn’t have to be.

He took the time to talk about the UAW members at Cornell University — dining workers, gardeners, custodians, and facilities workers — who just the night before “had to walk out on strike for a better life because they’re fighting corporate greed, and our only hope is to attack corporate greed head-on.”

Fain used the phrase “the working class” over and over again in a way that no one but Bernie Sanders has done in a DNC speech in recent memory. He took on Trump’s pseudo-populist nonsense in a way that few other speakers could do with as much credibility, recalling Trump’s lying promise in 2016 in Lordstown, Ohio, to bring back lost auto jobs, and Trump’s conversation with Elon Musk last week on Twitter where the two billionaires “laugh[ed] about firing workers who go on strike.” (The Trump/Musk conversation is now the basis of a formal unfair labor practices claim by the UAW.)

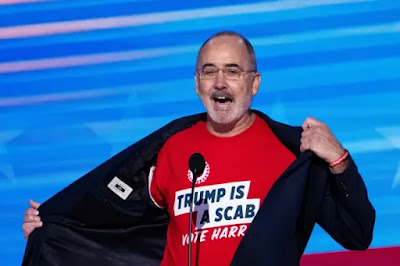

In a more low-key nod to the Hulk Hogan speech at the Republican National Convention (RNC), where Hogan ripped off his shirt to reveal a “Trump/Vance” T-shirt underneath, Fain took off his blazer to reveal a T-shirt bearing a slogan that he had the crowd enthusiastically chanting several times — “Trump is a Scab.”

This is exactly the right way to attack Trump. The contrast couldn’t be more extreme between Pritzker preening about being a “real” billionaire and Fain dismissing Trump and J. D. Vance in his 2024 DNC speech as “two lapdogs for the billionaire class.”

At the RNC, the hall was full of delegates waving mass-printed signs demanding “Mass Deportations Now.” At the DNC, Fain identified this demagoguery for what it was:

Donald Trump the scab . . . is pushing [the] divide and conquer tactics of the rich. It’s the oldest trick in the book. They want to blame the frustrations of working-class people . . . on some destitute and desperate person at the border. They do that because they want working-class people to be divided and to . . . keep the focus off the one true enemy — corporate greed. The rich think we’re stupid but working-class Americans see this for what it is.

The logic of his position here is simple. Blaming low wages and lost jobs on competition from a more desperate section of the working class is grotesquely hypocritical when it comes from politicians like Trump and Vance who manifestly don’t care about jobs and wages in any other context. And the position itself doesn’t make sense.

If undocumented workers are given a way to become American citizens, they can come out of the shadows and join unions, or take employers who break labor laws to court, without fear of deportation. The most conservative estimate for the total number of unauthorized immigrants in the United States puts it at about eleven million. Even if Trump and Vance escalate the already brutal machinery of deportation with some creative new forms of base-pleasing performative cruelty, it’s unlikely that they’ll be able to escalate all the way to the kind of dystopian police-state tactics it would take to successfully round up eleven million people who in the overwhelming majority of cases are just trying to keep their heads down and live their lives. The practical effect, instead, will be to make the majority of them that much more terrified and thus that much easier to hyperexploit — which will drive wages down for everyone.

Fain’s speech gestured at a way forward based on solidarity between these workers and the native-born section of the working class. This isn’t just a morally better solution to the problem posed by this hyperexploitation than “mass deportations now.” It’s the only approach that might actually work.

Fain for President

The speech wasn’t perfect. Fain heaped far more praise on Harris than she deserves, especially given her campaign’s repeated abandonment of social democratic policies she’d supported as a senator, like Medicare for All and a federal jobs guarantee, that would massively benefit workers and decrease the power of the billionaire class.

And most glaringly of all, Fain didn’t mention Gaza. The UAW as an organization has long called for a cease-fire, and Fain himself has spoken forcefully about the “slaughter and devastation” being inflicted by the Israeli military and the urgent need to end the war. Perhaps Fain simply calculated that there was no plausible way within the bounds of a ten-minute speech to square the circle of his deep disagreements with Harris on these subjects with his union’s understandable support for her against Trump, who spent his first term stacking the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) with hardcore union-busters.

What this really shows is that leaders like Fain who are trying to take meaningful action against the “one true enemy” of corporate power deserve far better political representation than they’re getting from the Democratic Party. With the choices currently narrowed to two of them, it makes sense that the Fains of the world prefer Harris to “Donald Trump the Scab.” But the American working class as a whole deserves better going forward. In 2028 or 2032, it would be nice to see Fain run himself.

Maybe he’ll never do that. He might calculate that he can do more good at the UAW than he can in electoral politics. But hopefully someone picks up that torch. Because the politics of broad working-class unity against the billionaires and all of their lapdogs is exactly what we need.

By Shawn Fain, Maximillian Alvarez

Shawn Fain, president of the United Auto Workers, didn’t mince words in his speech at the 2024 Democratic National Convention. Wearing a shirt with the words “TRUMP IS A SCAB” emblazoned on the front, Fain told the crowd, “For the UAW and for working people everywhere, it comes down one question: what side are you on? On one side we have Kamala Harris and Tim Walz, who have stood shoulder to shoulder with the working class. On the other side, we have Trump and Vance, two lap dogs for the billionaire class who only serve themselves.” In this exclusive interview, TRNN Editor-in-Chief Maximillian Alvarez speaks with Fain at the DNC about why the UAW has endorsed Harris-Walz, what is at stake in this election for working people and the labor movement, and which side of the class war Donald Trump is on.

Studio: Kayla Rivara

Post-Production: Adam Coley