MARYLAND

Larry Hogan and Race: It Ain’t Pretty

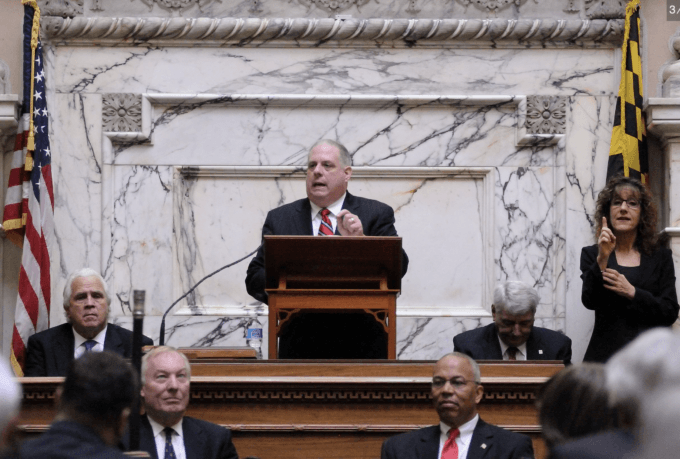

Maryland Governor Larry Hogan giving the State of the State address in 2016. Photo: Maryland Governor’s Office.

Maybe it’s a small thing but I still can’t get over a line from Larry Hogan’s 2020 memoir. It’s about the first covid death to occur on Hogan’s watch as Maryland governor, the job he held from 2015 to 2023.

“[It was] a Prince George’s County man in his sixties who had underlying medical issues,” Hogan writes. “Terrible news, but you couldn’t exactly call it a surprise.”

It’s those last words – you couldn’t exactly call it a surprise – that disturb me.

This man was a constituent of Hogan’s and likely suffered a painful death, yet Hogan can do little more than shrug his shoulders. And I wonder if that has something to do with this man having been from Prince George’s, a majority Black county. (I wasn’t able to confirm the man’s race or name.)

If this line from Hogan’s memoir was a one-off it wouldn’t have stuck in my craw. But it’s all too consistent with Hogan’s troubling record on race, which has received scant attention over the years.

The election is Tuesday and Hogan is back on the ballot – this time as a candidate for Senate. If he wins, it’ll ensure Republican control of that body.

Since time is tight, I’ll limit my focus to Hogan’s record on race as it pertains to his covid response (which was also scandalous for other reasons).

Anne Arundel ‘Throwback’

From nearly the moment covid struck, it was clear that Black and Brown communities would be hardest hit. With thoughtful and robust interventions, however, the damage could have been lessened. But from the jump, Hogan made clear that he was taking a different approach.

Hogan could’ve tapped a Black official or a sophisticated white one to help localities combat existing disparities and save lives. Instead, Hogan chose Steve Schuh to be his covid liaison to local leaders, a move that left me speechless.

Schuh is part of a crew of Republicans from Anne Arundel County, where Hogan hails from, that run the gamut from retrograde to racist. I reported on these guys back in 2018, when Schuh was running for a second term as county executive, and Hogan for a second term as governor, with the two happily endorsing each other.

In addition to Hogan, that year Schuh also backed John Grasso, an Anne Arundel County councilman running for state senate. “John Grasso is motivated by [one] thing,” Schuh told the Capital Gazette: “He wants to make the community a better place. He wants to help people and animals.”

But Grasso’s Facebook posts told a different story. One post accused former President Obama of being “the bastard child of a bigamous marriage between two Communists,” who grew up to become a male prostitute who “had sex with older white men in exchange for cocaine.” Another Grasso post took aim at the LGBTQ community: “Folks keep talkin’ about another civil war. One side has 8 trillion bullets. The other doesn’t know which bathroom to use.”

Despite these and other such outbursts, Schuh – who Hogan would later tap to be his covid liaison – stood by Grasso, as well as an even more extreme fellow Anne Arundel Republican.

From my 2018 Counterpunch story:

“Up until the eve of his 2014 election to the Anne Arundel County Council, [Michael] Peroutka was a member of the League of the South, which the Southern Poverty Law Center classifies as a hate group. Even as a councilman, Peroutka continued supporting some of the group’s positions. It wasn’t until June 2017, just days before neo-Nazi David Duke keynoted the League of the South’s annual conference, that Peroutka finally denounced the group. Six months later, in a party-line vote, all four Republicans on the Anne Arundel County Council elected Peroutka Council chairman, his present position.

“While Hogan doesn’t support Peroutka, he’s not that far removed from him. The governor supports County Executive Schuh, who in turn backs Peroutka, calling him ‘a throwback’ who ‘does not have a malicious bone in his body.’”

Unlike Schuh, Hogan publicly distanced himself from Grasso and Peroutka. Still, Hogan showed up in campaign literature with Peroutka in 2014 and Grasso in 2018 – both times unbeknownst to him, Hogan said.

Unfortunately for the Anne Arundel gang, 2018 proved to be a watershed year in the county’s politics, and Schuh, Grasso and Peroutka all went down to defeat. (Peroutka would briefly resurface in 2022 as the Republican nominee for Maryland attorney general.)

Of the Anne Arundel crew, only Hogan won in 2018, beating back Ben Jealous, the youngest ever head of the NAACP. (When Jealous called to concede on election night, Hogan refused to take the call, then boasted about it in his memoir.)

Schuh, meanwhile, wasn’t out in the cold for long. The month after his loss, Hogan named his ally to a cushy post directing Maryland’s response to the opioid epidemic.

When covid hit, Hogan gave Schuh – someone who’d openly backed bigots – an additional role as the administration’s covid liaison to localities, like Baltimore City and Prince George’s.

Meanwhile, during the first six months of Maryland’s covid lockdown, white suicides fell by almost half, even as Black suicides nearly doubled, according to a Johns Hopkins University study published as a research letter in JAMA Psychiatry.

Black shots

Still, when it came to getting covid shots into people’s arms, Maryland fared well compared to other states. But even here there were issues of fairness.

As embarrassing news stories began to trickle out regarding how whites in Maryland had far more access to vaccines than Blacks, Hogan needed someone to blame.

“We have supply chain issues everywhere in the country,” Hogan said, “but in minority communities the additional problem is people are refusing to take the vaccine.”

With his remark, Hogan wasn’t just “blaming the victim” – as the head of the University of Maryland’s Center for Health Equity put it – he was also lying.

There’s “little difference in reluctance to take the coronavirus vaccine among Black and White Marylanders,” the Washington Post reported at the time.

Even as Hogan blamed Blacks for not getting the shot, he also blamed them for getting too many. “Baltimore City had gotten far more than they were really entitled to,” Hogan said.

“I think our citizens in Baltimore know a dog whistle when they see one,” Baltimore Mayor Brandon Scott responded.

Like father like son

Prince George’s was hit particularly hard by covid. That’s due in part to the county’s antiquated tax structure.

If you were to pick a year when the trajectory of Prince George’s departed from that of its better-off neighbors, it’d be 1978. That’s when Prince George’s then-white majority put the county government in a chokehold by depriving it of tax revenue to prevent the increasing Black population from benefitting from quality schools and other public services.

The 1978 referendum – known as Tax Reform Initiative by Marylanders or TRIM – “passed just as Prince George’s County began a demographic transition from majority-white to majority-Black,” DW Rowlands wrote in a 2020 story for Greater Greater Washington. “A major motivation for its passage was the desire of white voters to limit funding for a public school student body that was becoming increasingly Black and integrated — four years earlier, in 1974, Prince George’s school system had become the largest in the country to be subject to a court-ordered busing desegregation plan. Holding property tax revenue constant while the county’s population was rapidly growing led to severe cuts to many county services and increases to fees.”

One of the leaders of this ugly movement was none other than Larry Hogan’s father, Larry Hogan, Sr., who was the last Republican to serve as Prince George’s County Executive from 1978 to 1982.

Today, this very post is held by Angela Alsobrooks, although maybe not for much longer. If polls are to be believed, come Tuesday Alsobrooks will defeat Hogan and become just the third Black woman ever to serve in the Senate.