Cop’s own economists say the Global South needs 2.4 trillion dollars to cope with extreme weather and switch economies away from fossil fuels

A climate march in London as the Cop talks too place

By Camilla Royle

Sunday 24 November 2024

Last year was the hottest on record—and 2024 looks set to break this record again. This will lead to flash flooding, storms and droughts. Temperatures already exceeded the target that was agreed at the Paris climate talks in 2015—1.5 degrees above pre-industrial levels—for part of this year.

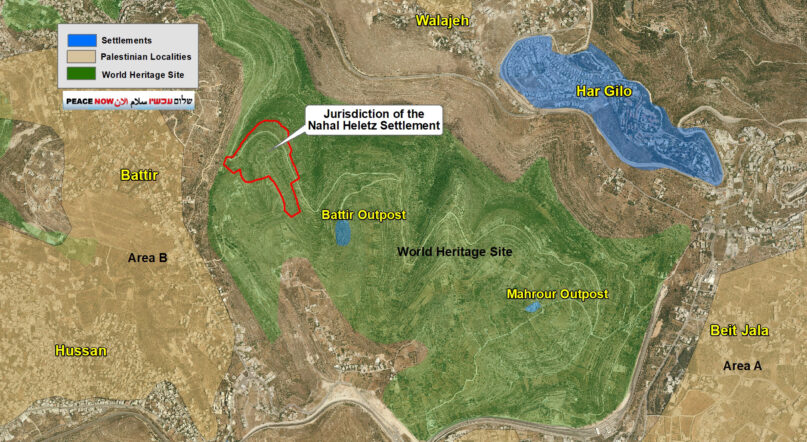

This was meant to be the “finance Cop”. Global South countries have been asking for a trillion dollars per year from the Global North to help them deal with the effects of climate change.

Yet the richer countries only agreed to pay £238 billion and this would only be delivered by 2035. Panama’s lead negotiator Juan Carlos Monterrey Gomez said the amounts being offered were “outrageous, evil and remorseless”. He said, “They offer crumbs while we bear the dead.”

At one point, Global South delegates walked out of the talks in disgust. They included many representatives of small island states who fear being swamped by rising sea levels.

Cop’s own economists say the Global South needs 2.4 trillion dollars to cope with extreme weather and switch economies away from fossil fuels.

The Cop talks have provided an opportunity for oil-rich states to try to protect their domestic fossil fuel industries and water down agreements.

Last year the talks agreed to accelerate efforts towards “the phase-down of unabated coal power”. This came nowhere close to the rapid shutdown of all new fossil fuel extraction that is needed.

This year delegates have lobbied against even these weak proposals. Saudi Arabia opposed any inclusion of measures to “transition away from fossil fuels”.

Albara Tawfiq from the Saudi delegation said it “will not accept any text that targets any specific sectors, including fossil fuels”. Delegates from China also spoke out against specific pledges over fossil fuels.

Bolivia’s delegates opposed it on the basis that richer countries should cut their own emissions before telling the Global South not to develop fossil fuel industries.

A giant natural gas field has recently been discovered in Bolivia, which the country’s leaders hope will help revive the economy. But gas exploration in the Latin American country has angered environmental and indigenous groups.

Delegates from Colombia took a different stance. Susana Muhamad is the environment minister in the left wing government that came to office two years ago and pledged to phase out fossil fuel production. “What is the point of having an agreement and a convention if we cannot deal with the issue that creates the problem?” she asked.

The Cop talks took place in Baku in Azerbaijan, a centre of the fossil fuel industry. Azerbaijan plans to increase its exports of gas to countries in the West which no longer want to import gas from Russia.

But it also played a major role in supplying oil to the eastern Mediterranean via the BTS pipeline— including to Israel.

Labour energy secretary Ed Miliband gave a speech at the talks. He admitted that the Cop process is “imperfect” but added that it is “the best process we have got”.

Miliband said that an expansion of clean energy will lead to economic growth. He said, “It is right for tackling the climate crisis and for the face of future generations. And it is right economically for Britain because it will spur jobs and export opportunities and help businesses.”

The Labour government announced at the start of the Cop talks that it wants to cut emissions by 81 percent by 2035. That’s a slight increase on the 78 percent pledge from the previous Tory government. Miliband has said he wouldn’t issue new oil and gas licences to achieve this.

Yet while Labour make bold speeches about global ambition and deep emissions cuts, their plans involve massive investment in carbon capture and storage technologies. Experts say this will deepen Britain’s dependence on oil and gas.

And the government is committed to working with climate change denying United States president Donald Trump. Miliband has said that he wants to find “common ground” and “work with all countries to move forward on this really important issue”.

Labour is presiding over a fossil fuelled capitalist system that is driving us towards disaster.