How a drug used to treat parasites for decades became the hot and controversial drug of the pandemic

Feb. 7, 2022

By Jaimy Lee

MARKETWATCH PHOTO ILLUSTRATION/ISTOCKPHOTO

MARKETWATCH PHOTO ILLUSTRATION/ISTOCKPHOTO

LONG READ

Last May, a graduate student named Jack Lawrence sat down in his apartment and began combing through a medical study about ivermectin for his coursework at the University of London.

The study, conducted by researchers at Benha University in Egypt and published in November 2020, had produced stunning results. It found that ivermectin, an antiparasitic drug that’s been around for decades, could reduce the risk of death among COVID-19 patients by 90%, among other findings.

“Suddenly, I started noticing something,” Lawrence said. “Although there [were] a lot of parts of the paper that were badly written, there are also a few sentences which had perfect grammar, perfect everything, and could have been plucked right out of another scientific paper. And, in fact, they were. I put them into Google. Each of these sentences got a hit.”

Lawrence, who is in his mid-20s and studying biomedical science, kept researching online. He clicked through to a file-sharing website, where the study’s dataset was housed. Lawrence paid $10.80 for a subscription to reactivate the link, which had expired in January 2021, only to find the file required a password. He made a few attempts, and then he tried “1-2-3-4.” It worked.

From there, Lawrence discovered that the issues went far beyond plagiarism. The number of deaths cited in the paper did not match the number of deaths in the database. Some of the patient data had been duplicated. Other patients included in the trial had been hospitalized before the study began.

“I was working in my room,” he said. “And I went out of my room to tell everyone, you know, my housemates, being like, ‘Oh, my God, you will not believe what I’ve just found.’ ”

Lawrence would go on to contact Research Square, the website that published the paper, which had not been peer-reviewed. Within 24 hours, Lawrence got a response from the editor, and the website withdrew the paper in mid-July.

It’s just one of several retractions and withdrawals of studies pointing to ivermectin as a viable COVID-19 treatment, and the impact of this kind of fraudulent research is still reverberating. During the pandemic, there has been a surge of demand for ivermectin, a drug commonly used to treat parasites in people who live in regions of South America and Africa, as well as in livestock.

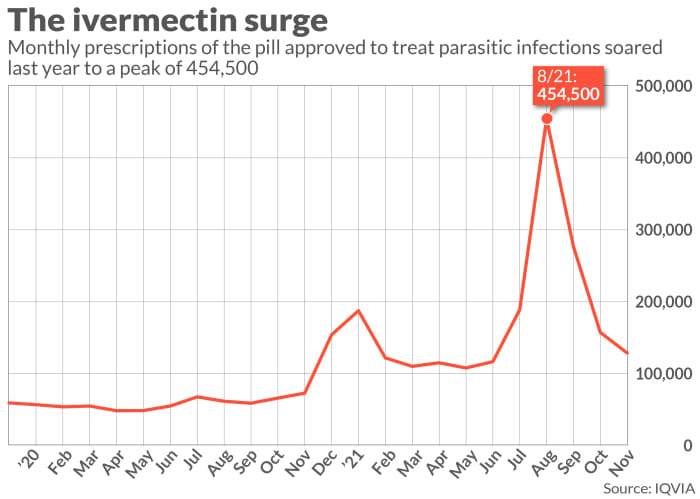

The number of monthly ivermectin prescriptions in the U.S. jumped to a high of 454,000 in August 2021, from about 57,000 in January 2020, according to healthcare data firm IQVIA. This figure doesn’t take into account veterinary prescriptions, which also increased when people began to seek out novel means of gaining access to the drug. Research published in January estimates that health insurers spent about $2.5 million on ivermectin prescriptions for COVID-19 in one week of August 2021.

The Benha research was cited in a doctor’s congressional testimony before it was debunked, and the drug has been touted by celebrities and politicians, as well as a mysterious and popular website with no known authors. Ivermectin proponents describe the drug as cheap, safe and readily available, and say it can work as both a COVID-19 treatment and prophylaxis.

Yet no comprehensive clinical trials have found that ivermectin works as a COVID-19 treatment. To make this issue even more complicated, no “gold standard” studies have yet found explicitly that it’s useless against COVID-19 or that it’s harmful to people taking it.

The ivermectin saga shows how the American drug regulatory system has been overrun by the pressures of the pandemic, including the rush to put out new research and then act immediately on those findings. This led a graduate student hacking into a database to find the truth, and the Food and Drug Administration cracking online jokes to warn people that ivermectin was not a suitable COVID-19 treatment. “You are not a horse,” the U.S. regulator tweeted in August, in an attempt to stop Americans from using ivermectin, warning the drug could be toxic if taken at the highly concentrated doses given to large animals.

Gideon Meyerowitz-Katz, an Australian epidemiologist who has become an expert on ivermectin during the pandemic, says it’s not unreasonable for the average person to think ivermectin is a solid COVID-19 treatment. After all, the public is watching trusted people recommend or take the drug. But he thinks they are being misled.

“A lot of the debate and discussion is driven by people who, for whatever reason, think ivermectin is a miracle cure, even despite the evidence that it probably isn’t,” Meyerowitz-Katz said. “It’s become incredibly politicized at this point.”

There will be new data coming soon from a pair of randomized clinical trials that may reveal just how effective ivermectin is as a COVID-19 treatment. Dr. David Boulware, an infectious-disease physician and scientist in charge of one of those ivermectin studies, says the whole point of testing drugs in people is to generate such definitive data.

“There’s tons of people prescribing [ivermectin], but there’s actually very little data,” Boulware says.

Ivermectin boosters: Sen. Ron Johnson, a Wisconsin Republican, and Dr. Pierre Kory. DREW ANGERER/GETTY IMAGES

A series of low-quality studies and a ‘miracle drug’

To really understand ivermectin’s roots as a COVID-19 treatment in the U.S., you have to look to Wisconsin, home to Senate Republican Ron Johnson, Green Bay Packers quarterback Aaron Rodgers and Dr. Pierre Kory. Each is a prominent American figure in the ivermectin story.

While Kory is not famous, he and an organization he helped found have played a big role in popularizing ivermectin as a COVID-19 treatment. A critical-care physician, Kory practiced medicine at University of Wisconsin Health in Madison until he resigned over his frustration with the hospital’s COVID-19 care practices. Now he’s one of the founders of the Front Line COVID-19 Critical Care Alliance, an organization known as FLCCC that promotes an outpatient, inpatient and long-COVID treatment plan.

Kory remembers when the first preprint assessing ivermectin’s viability as a COVID-19 treatment was published in April 2020. Preprints, which are studies that haven’t been reviewed by other experts, have long been used in economics and math, but they became widely used in the pandemic to speed up the dissemination of new medical and scientific findings. The ivermectin preprint that got Kory’s attention had been published by researchers in Australia. It described an in-vitro study, meaning it was conducted in a laboratory and not in people or animals. In very large doses, ivermectin demonstrated antiviral action against the virus.

By Jaimy Lee

MARKETWATCH PHOTO ILLUSTRATION/ISTOCKPHOTO

MARKETWATCH PHOTO ILLUSTRATION/ISTOCKPHOTOLONG READ

Last May, a graduate student named Jack Lawrence sat down in his apartment and began combing through a medical study about ivermectin for his coursework at the University of London.

The study, conducted by researchers at Benha University in Egypt and published in November 2020, had produced stunning results. It found that ivermectin, an antiparasitic drug that’s been around for decades, could reduce the risk of death among COVID-19 patients by 90%, among other findings.

“Suddenly, I started noticing something,” Lawrence said. “Although there [were] a lot of parts of the paper that were badly written, there are also a few sentences which had perfect grammar, perfect everything, and could have been plucked right out of another scientific paper. And, in fact, they were. I put them into Google. Each of these sentences got a hit.”

Lawrence, who is in his mid-20s and studying biomedical science, kept researching online. He clicked through to a file-sharing website, where the study’s dataset was housed. Lawrence paid $10.80 for a subscription to reactivate the link, which had expired in January 2021, only to find the file required a password. He made a few attempts, and then he tried “1-2-3-4.” It worked.

From there, Lawrence discovered that the issues went far beyond plagiarism. The number of deaths cited in the paper did not match the number of deaths in the database. Some of the patient data had been duplicated. Other patients included in the trial had been hospitalized before the study began.

“I was working in my room,” he said. “And I went out of my room to tell everyone, you know, my housemates, being like, ‘Oh, my God, you will not believe what I’ve just found.’ ”

Lawrence would go on to contact Research Square, the website that published the paper, which had not been peer-reviewed. Within 24 hours, Lawrence got a response from the editor, and the website withdrew the paper in mid-July.

It’s just one of several retractions and withdrawals of studies pointing to ivermectin as a viable COVID-19 treatment, and the impact of this kind of fraudulent research is still reverberating. During the pandemic, there has been a surge of demand for ivermectin, a drug commonly used to treat parasites in people who live in regions of South America and Africa, as well as in livestock.

The number of monthly ivermectin prescriptions in the U.S. jumped to a high of 454,000 in August 2021, from about 57,000 in January 2020, according to healthcare data firm IQVIA. This figure doesn’t take into account veterinary prescriptions, which also increased when people began to seek out novel means of gaining access to the drug. Research published in January estimates that health insurers spent about $2.5 million on ivermectin prescriptions for COVID-19 in one week of August 2021.

The Benha research was cited in a doctor’s congressional testimony before it was debunked, and the drug has been touted by celebrities and politicians, as well as a mysterious and popular website with no known authors. Ivermectin proponents describe the drug as cheap, safe and readily available, and say it can work as both a COVID-19 treatment and prophylaxis.

Yet no comprehensive clinical trials have found that ivermectin works as a COVID-19 treatment. To make this issue even more complicated, no “gold standard” studies have yet found explicitly that it’s useless against COVID-19 or that it’s harmful to people taking it.

The ivermectin saga shows how the American drug regulatory system has been overrun by the pressures of the pandemic, including the rush to put out new research and then act immediately on those findings. This led a graduate student hacking into a database to find the truth, and the Food and Drug Administration cracking online jokes to warn people that ivermectin was not a suitable COVID-19 treatment. “You are not a horse,” the U.S. regulator tweeted in August, in an attempt to stop Americans from using ivermectin, warning the drug could be toxic if taken at the highly concentrated doses given to large animals.

Gideon Meyerowitz-Katz, an Australian epidemiologist who has become an expert on ivermectin during the pandemic, says it’s not unreasonable for the average person to think ivermectin is a solid COVID-19 treatment. After all, the public is watching trusted people recommend or take the drug. But he thinks they are being misled.

“A lot of the debate and discussion is driven by people who, for whatever reason, think ivermectin is a miracle cure, even despite the evidence that it probably isn’t,” Meyerowitz-Katz said. “It’s become incredibly politicized at this point.”

There will be new data coming soon from a pair of randomized clinical trials that may reveal just how effective ivermectin is as a COVID-19 treatment. Dr. David Boulware, an infectious-disease physician and scientist in charge of one of those ivermectin studies, says the whole point of testing drugs in people is to generate such definitive data.

“There’s tons of people prescribing [ivermectin], but there’s actually very little data,” Boulware says.

Ivermectin boosters: Sen. Ron Johnson, a Wisconsin Republican, and Dr. Pierre Kory. DREW ANGERER/GETTY IMAGES

A series of low-quality studies and a ‘miracle drug’

To really understand ivermectin’s roots as a COVID-19 treatment in the U.S., you have to look to Wisconsin, home to Senate Republican Ron Johnson, Green Bay Packers quarterback Aaron Rodgers and Dr. Pierre Kory. Each is a prominent American figure in the ivermectin story.

While Kory is not famous, he and an organization he helped found have played a big role in popularizing ivermectin as a COVID-19 treatment. A critical-care physician, Kory practiced medicine at University of Wisconsin Health in Madison until he resigned over his frustration with the hospital’s COVID-19 care practices. Now he’s one of the founders of the Front Line COVID-19 Critical Care Alliance, an organization known as FLCCC that promotes an outpatient, inpatient and long-COVID treatment plan.

Kory remembers when the first preprint assessing ivermectin’s viability as a COVID-19 treatment was published in April 2020. Preprints, which are studies that haven’t been reviewed by other experts, have long been used in economics and math, but they became widely used in the pandemic to speed up the dissemination of new medical and scientific findings. The ivermectin preprint that got Kory’s attention had been published by researchers in Australia. It described an in-vitro study, meaning it was conducted in a laboratory and not in people or animals. In very large doses, ivermectin demonstrated antiviral action against the virus.

“A lot of the debate and discussion is driven by people who, for whatever reason, think ivermectin is a miracle cure, even despite the evidence that it probably isn’t.”

— Gideon Meyerowitz-Katz, University of Wollongong

Some researchers had immediately disregarded the study, despite its being well-designed, based on the dosing.

“I saw that when it came out, and I did the mathematical calculation of, is this a drug level you can achieve?” Boulware told me. “I quickly realized, no, this is 50 to 100 times higher than you’d ever get in a human. It took me about 15 minutes to figure out that this was not going to be useful as an antiviral. I set it aside and moved onwards.”

There was little interest in ivermectin in the U.S. in those days, though the FDA began warning people that same month not to self-medicate with ivermectin formulations intended for animals. Ivermectin is considered a very good and safe treatment for parasitic worms that can cause diseases in people like river blindness, and is also used to treat worms in livestock and pets.

In the spring and summer of 2020, much of the nation’s focus was on three other therapies: hydroxychloroquine, a drug that received emergency-use authorization as a COVID-19 treatment in March 2020; convalescent plasma, which received an EUA of its own in August 2020; and Gilead Sciences’ GILD, -0.22% remdesivir, an antiviral that was eventually approved by the FDA and is now considered part of the standard of COVID-19 care for very sick patients.

“What then happened was a series of very low-quality studies published towards the end of [2020], and they reported huge benefits for ivermectin,” Meyerowitz-Katz said.

It was around October of that year that Kory, back in Wisconsin, says he saw promising preliminary data out of research conducted in Bangladesh, the Dominican Republic and Peru. He began prescribing ivermectin to COVID-19 patients.

At that time, Roche Holding’s ROG, -0.13% “tocilizumab was not looking good. Hydroxychloroquine from the randomized control trials was not looking good. Convalescent plasma. … These are all things that were being used therapeutically,” Kory said. “And when we saw ivermectin — this is mid-October 2020 —w e were just astounded by the consistency and reproducibility from a number of different trials from countries around the world.”

Within a month, the FLCCC published its first outpatient COVID-19 protocol, which included ivermectin. Then Johnson extended a second invitation to Kory to testify before Congress.

At a Senate hearing on Dec. 8, 2020, three days before the first COVID-19 vaccine was authorized in the U.S., Kory’s testimony described ivermectin as a “miracle drug” that could be used more quickly than the vaccines, which would take months to roll out. His testimony several times referenced the Benha University preprint promising major clinical benefits, and video of the testimony went viral on YouTube.

“Nearly all studies are demonstrating the therapeutic potency and safety of ivermectin in preventing transmission and progression of illness in nearly all who take the drug,” Kory wrote in his prepared testimony.

The video of the testimony was removed from YouTube, but ivermectin’s ascension into the mainstream had begun. The number of ivermectin prescriptions in the U.S. doubled in a single month — to nearly 154,000 scripts in December 2020, from 72,000 in November 2020, according to the IQVIA data.

From that point on, it became clear that there was a fan base dedicated to ivermectin and its purported COVID-19 benefits. Politicians like Johnson and Rep. Marjorie Taylor Greene, a first-term Republican from Georgia, touted it. Rodgers, the famous quarterback, and conservative talk-show host Glenn Beck both said in interviews that they had taken it after testing positive for the virus. So did Joe Rogan, who also talked about the benefits on his popular Spotify SPOT, -1.67% podcast, where he described getting a recommendation for ivermectin from Kory.

Pandemic prescription: Ivermectin has become a popular COVID-19 treatment amid an absence of good data. AP PHOTO/MIKE STEWART

‘Studies that probably never happened’

The ivermectin story changed as Jack Lawrence, the University of London graduate student, started contacting other researchers to verify his initial findings in the flawed Benha preprint.

In June 2021, he reached out to Nick Brown, a psychologist and researcher at Linnaeus University in Sweden known for hunting fraud in research, who connected him to Meyerowitz-Katz, the Australian epidemiologist. Lawrence essentially asked them to double-check his work before messaging Research Square about what he’d found. He was just a graduate student and wanted to make sure he hadn’t missed something.

“I’d read about [Brown] before,” Lawrence said, “so I sent him that, and he immediately found a whole range of different duplicate values, far more than I could ever have found.”

Michele Avissar-Whiting, Research Square’s editor in chief, said in a statement that, “based on what Jack found, we have reason to believe the preprint’s conclusions are compromised, so the withdrawal was done to stop its propagation as sound science.”

It was one of the most high-profile retractions of ivermectin research to date, but it was not the first. The problems have also extended to peer-reviewed work. In mid-2020, an ivermectin study published in the prestigious New England Journal of Medicine was retracted. It included data from Surgisphere, a company that also provided inaccurate patient data to a study about hydroxychloroquine, which was retracted, as well. Experts say the peer-reviewed study was especially problematic because its findings had been used to inform Peru’s decision to allow ivermectin as a COVID-19 drug in the early months of the pandemic. (That approval was revoked in 2021, according to the Guardian.)

Then came the Benha retraction. Next up was a meta-analysis of trials that treated COVID-19 patients with ivermectin, published last summer in Open Forum Infectious Diseases. It had to be corrected in August 2021 as having cited a fraudulent study. (Andrew Hill, one of the paper’s authors and a researcher at the University of Liverpool, wrote last fall in the Guardian that he received death threats after he revised his research.)

The Journal of Antibiotics in September retracted a study published in June, saying the editor was no longer confident in the research’s findings. This was followed by the October retraction of a study conducted by researchers in Lebanon and published in the journal Viruses that said ivermectin reduced symptoms and lowered viral load. In November, the Journal of Intensive Care Medicine retracted research published by FLCCC physicians over concerns about the accuracy of some of the data.

“We can say with some confidence at this point that the very large benefits that people were proposing for ivermectin were based on studies that probably never happened,” Meyerowitz-Katz said. “There may still be benefits for ivermectin, but they’re probably going to be quite a bit smaller than many people had hoped earlier [in 2021], when they were relying on this potentially fabricated research.”

What is unclear is whether the retractions and withdrawals of some of the key scientific data underpinning the case for ivermectin will change anything for the people who believe in the drug’s potential.

“What people are doing [is] essentially weaponizing the scientific self-correction process, which, by the way, is a very flawed process,” said Ivan Oransky, a longtime healthcare journalist and co-founder of Retraction Watch, a site that tracks retractions in scientific research. “What they’re doing is sort of weaponizing any corrections or any retractions or any sort of doubt — the kind of skepticism you want — and turning it into why they’re right.”

Kory now says the Benha study is deeply flawed — “that paper stinks,” he told me — but he puts the blame for the wave of retractions and withdrawals of ivermectin studies on pharmaceutical companies that he said have spent decades developing disinformation campaigns that aim to restrict the repurposing of cheap generic drugs.

“It would dry up the sales of remdesivir and Paxlovid and molnupiravir,” said Kory, referring to some of the most prominent therapeutics, developed by Gilead, Pfizer PFE, +0.40% and Merck & Co. MRK, -1.25%, which have been authorized to treat COVID-19. “You name it. Monoclonal antibodies. It literally threatened the market value of almost anything out there on a global pandemic.” Kory added: “What we’re talking about, a historic corruption, the disinformation campaign waged against a repurposed drug.”

Still, even simple scientific information has been falsely used to promote the effectiveness of ivermectin. For example, some ivermectin proponents, including House Republican Greene, cite the fact that the scientists who discovered ivermectin won a Nobel Prize in 2015, without making clear the prestigious award was given in recognition of the drug’s effectiveness against parasitic disease, and had nothing to do with COVID-19.

“People who are drawn to these sorts of ideas like doing their own research and like happening upon these very convenient Easter egg–type facts,” said Philip Corlett, an associate professor of psychiatry at Yale School of Medicine who has researched paranoia in the pandemic. “They’re like, ‘I found it. The mainstream medical establishment and the media ignored it.’ … It becomes something that you’ve cultivated. You’ve uncovered it. You’ve helped propagate. You feel a real sense of belonging over it, too.”

For those who have been involved in ensuring the scientific data about ivermectin is up to snuff, the combination of the pandemic and armchair epidemiology has at times been unsettling. Retraction Watch’s Oransky says he’s worried about the tone of some tweets that have mentioned an old home address, which is where he had originally registered the organization that houses Retraction Watch. “You get scared a little bit,” Oransky said.

TERRENCE HORAN/MARKETWATCH

A mysterious website

There’s one website often cited by ivermectin’s supporters: c19early.com. It’s got a clean, white layout and says it has pulled together “real-time analysis of 1,387 studies” for a wide-ranging list of potential COVID-19 therapies that can be used for early treatment, as of Feb. 7. It includes URLs like Ivmmeta.com and Hcqmeta.com.

No one I spoke with, including Kory, knows who runs the website. The website’s Twitter account has been suspended, and emails asking for information about who owns or operates the site were not returned. Some of the treatment protocols listed are provided by the FLCCC.

“It would be fascinating to know who’s behind such a massive effort,” Meyerowitz-Katz said. “It’s pseudoscientific nonsense, but it is also absolutely a huge effort.”

When I first dropped a sentence written several times on the site — “Elimination of COVID-19 is a race against viral evolution” — into Google, several websites with URLs that have nothing to do with COVID-19 or healthcare pop up with that description. Many of the top search results lead to online pages that have been moved or deleted, but one link redirects to a website selling Stromectol, the brand name for the form of ivermectin marketed by drug giant Merck to treat parasitic worms. That site, which says it is owned by Canadian Pharmacy Ltd., lists phone numbers in London and New York City. Both go directly to a generic voicemail.

Boulware, who is based in Minneapolis, said he messaged a website promoting ivermectin about a year ago, to see if it would accept his help with the medical information being put out. The site has some great charts, he said, but, in some cases, the data were not valid. When the responses to his emails were returned in the middle of the night, it made him wonder if the site’s operators were based in a foreign country. He speculated that maybe the website could be Russian disinformation or coming from a generic-drug maker in India trying to skirt FDA regulations.

“Those websites are a lot of effort. They’re really detailed,” Boulware said. “So it’s got to be either someone who has a lot of free time on their hands, or someone’s got a financial motivation or a political-disinformation motivation.”

It’s become virtually impossible for anyone without a scientific background or a working knowledge of misinformation and disinformation to make sense of the sheer volume of information about the virus, treatments and vaccines that is generated every day — real or not.

About half of the 6,785 studies published in 2021 on the preprint server MedRxiv had to do with the pandemic.

“Every fact in COVID-19 context is being contested,” said Kasisomayajula Viswanath, a professor of health communication at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health. “Facts are changing constantly because the science is changing. And that has provided room for people to interpret it from their own perspective. I think that’s one reason. The second is because it has become extremely politicized.”

The people who believe ivermectin is a safe and effective COVID-19 treatment tend to be white men who are not vaccinated and identify as Republican voters, according to Liz Hamel, the director of public opinion and survey research at the Kaiser Family Foundation, which is conducting ongoing research on attitudes about COVID-19 during the pandemic.

“It seems to peak among 50- to 64-year-olds,” she said. “We do see that people over 65, regardless of partisanship, have been taking this disease more seriously. And young people tend to have more liberal political attitudes. So we often see that it’s people in the middle-age categories who stand out.”

But Kory said support for ivermectin as a COVID-19 treatment is not driven by political affiliation. “We’re not some right-wing conservative group,” Kory said. “In fact, the opposite. However, I don’t know whether it was the era of Trump that did it because he spoke well of hydroxychloroquine, but my take on the politicization of the science is that because our recommendations run contrary to the prevailing ones from the agencies, that means we’re a contrarian group.”

Even people who work in healthcare and medicine have had to learn how to interpret scientific research differently. In the past, companies or researchers conducted studies and then submitted the research to a medical journal, where it was peer-reviewed and then eventually published. Before the pandemic, the scientific process was much slower, usually taking months or even years to lock down a standard of care or scientific consensus. Now companies sometimes share snippets of data in news releases, and much of the pandemic research has been published first as a preprint and is only peer-reviewed later.

For people who are inexperienced with medical research, fragments of data and half-baked preprints can be even harder to decipher. They can be strung together and shared online with a link, and then picked up by politicians or media outlets. At the same time, algorithms are tracking what users are watching and reading and then serving up similar content to them.

“That’s what I call a spiral of amplification,” Viswanath said. “It starts small in some obscure corner — one study, one preprint — and or one person [or] group saying something, and a few groups talking about it on social media. Somehow it is picked up by certain political actors. And then it starts going mainstream. And that’s what has been happening with hydroxychloroquine, and that’s what has been happening with ivermectin.”

Last week Joe Rogan sent and deleted a tweet citing an incorrect report that a Japanese trial showed ivermectin to be clinically effective against COVID-19.

A mysterious website

There’s one website often cited by ivermectin’s supporters: c19early.com. It’s got a clean, white layout and says it has pulled together “real-time analysis of 1,387 studies” for a wide-ranging list of potential COVID-19 therapies that can be used for early treatment, as of Feb. 7. It includes URLs like Ivmmeta.com and Hcqmeta.com.

No one I spoke with, including Kory, knows who runs the website. The website’s Twitter account has been suspended, and emails asking for information about who owns or operates the site were not returned. Some of the treatment protocols listed are provided by the FLCCC.

“It would be fascinating to know who’s behind such a massive effort,” Meyerowitz-Katz said. “It’s pseudoscientific nonsense, but it is also absolutely a huge effort.”

When I first dropped a sentence written several times on the site — “Elimination of COVID-19 is a race against viral evolution” — into Google, several websites with URLs that have nothing to do with COVID-19 or healthcare pop up with that description. Many of the top search results lead to online pages that have been moved or deleted, but one link redirects to a website selling Stromectol, the brand name for the form of ivermectin marketed by drug giant Merck to treat parasitic worms. That site, which says it is owned by Canadian Pharmacy Ltd., lists phone numbers in London and New York City. Both go directly to a generic voicemail.

Boulware, who is based in Minneapolis, said he messaged a website promoting ivermectin about a year ago, to see if it would accept his help with the medical information being put out. The site has some great charts, he said, but, in some cases, the data were not valid. When the responses to his emails were returned in the middle of the night, it made him wonder if the site’s operators were based in a foreign country. He speculated that maybe the website could be Russian disinformation or coming from a generic-drug maker in India trying to skirt FDA regulations.

“Those websites are a lot of effort. They’re really detailed,” Boulware said. “So it’s got to be either someone who has a lot of free time on their hands, or someone’s got a financial motivation or a political-disinformation motivation.”

It’s become virtually impossible for anyone without a scientific background or a working knowledge of misinformation and disinformation to make sense of the sheer volume of information about the virus, treatments and vaccines that is generated every day — real or not.

About half of the 6,785 studies published in 2021 on the preprint server MedRxiv had to do with the pandemic.

“Every fact in COVID-19 context is being contested,” said Kasisomayajula Viswanath, a professor of health communication at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health. “Facts are changing constantly because the science is changing. And that has provided room for people to interpret it from their own perspective. I think that’s one reason. The second is because it has become extremely politicized.”

The people who believe ivermectin is a safe and effective COVID-19 treatment tend to be white men who are not vaccinated and identify as Republican voters, according to Liz Hamel, the director of public opinion and survey research at the Kaiser Family Foundation, which is conducting ongoing research on attitudes about COVID-19 during the pandemic.

“It seems to peak among 50- to 64-year-olds,” she said. “We do see that people over 65, regardless of partisanship, have been taking this disease more seriously. And young people tend to have more liberal political attitudes. So we often see that it’s people in the middle-age categories who stand out.”

But Kory said support for ivermectin as a COVID-19 treatment is not driven by political affiliation. “We’re not some right-wing conservative group,” Kory said. “In fact, the opposite. However, I don’t know whether it was the era of Trump that did it because he spoke well of hydroxychloroquine, but my take on the politicization of the science is that because our recommendations run contrary to the prevailing ones from the agencies, that means we’re a contrarian group.”

Even people who work in healthcare and medicine have had to learn how to interpret scientific research differently. In the past, companies or researchers conducted studies and then submitted the research to a medical journal, where it was peer-reviewed and then eventually published. Before the pandemic, the scientific process was much slower, usually taking months or even years to lock down a standard of care or scientific consensus. Now companies sometimes share snippets of data in news releases, and much of the pandemic research has been published first as a preprint and is only peer-reviewed later.

For people who are inexperienced with medical research, fragments of data and half-baked preprints can be even harder to decipher. They can be strung together and shared online with a link, and then picked up by politicians or media outlets. At the same time, algorithms are tracking what users are watching and reading and then serving up similar content to them.

“That’s what I call a spiral of amplification,” Viswanath said. “It starts small in some obscure corner — one study, one preprint — and or one person [or] group saying something, and a few groups talking about it on social media. Somehow it is picked up by certain political actors. And then it starts going mainstream. And that’s what has been happening with hydroxychloroquine, and that’s what has been happening with ivermectin.”

Last week Joe Rogan sent and deleted a tweet citing an incorrect report that a Japanese trial showed ivermectin to be clinically effective against COVID-19.

CARMEN MANDATO/GETTY IMAGES

Good data on ivermectin coming soon

Sometime this winter or early spring, a randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind trial sponsored by the National Institutes of Health that is testing ivermectin in 1,000 patients is expected to produce results, says Dr. Susanna Naggie, the vice dean for clinical research at Duke University’s medical school and the researcher running the trial.

The University of Minnesota’s randomized study has enrolled 1,196 participants, one-third of whom received ivermectin. (Both trials are evaluating several repurposed drugs as possible COVID-19 treatments.) Within the next few weeks, the Minnesota institution is expected to share the first findings from the ivermectin part of its trial, nearly two years after the first preprint examining ivermectin’s viability was published.

In pandemic time, this may feel overly slow, but, for the scientists conducting these trials, it’s still a pretty quick turnaround. The experts I spoke to seem to think that ivermectin could demonstrate a small benefit for some COVID-19 patients, but none think it’s likely that it will produce any of the major benefits promised by the fraudulent trials.

Edward Mills, a health-sciences professor at Canada’s McMaster University, is co-investigator of the Together clinical trial, another rigorous study that is evaluating nine different repurposed drugs as COVID-19 therapies, including ivermectin. It recently completed the ivermectin analysis but found it “did not demonstrate an important benefit,” Mills said in an email. The research may be published this month, he said.

Nevertheless, there is an idea circulating among scientists like Mills that ivermectin may be more likely to benefit COVID-19 patients in areas of the world with a high prevalence of parasitic worms. “What is possible is that co-infection of parasites with COVID may worsen health outcomes,” Mills said.

This is an idea also raised by Boulware, the scientist working on the University of Minnesota’s ivermectin study. Corticosteroids, like dexamethasone, are now considered the standard of care for severely ill COVID-19 patients; however, these drugs can cause what is called a “hyperinfection” and sometimes be fatal in a patient who has a parasitic infection. It’s possible that additional data about ivermectin gathered from different patient populations could show the drug being more beneficial in people who live in parasitic regions of the world, they say.

However, most native-born Americans don’t have parasites. And, since 2005, the U.S. policy has been to recommend that refugees from Africa, Asia, the Middle East, Latin America and the Caribbean receive treatment or presumptive antiparasitic treatment — including ivermectin — before arriving in the U.S.

“In certain patient populations, if you have a parasitic infection, it certainly can be beneficial if you’re giving steroids,” Boulware said. “Does that mean [as an] outpatient-setting early therapy in the U.S. that there’s a benefit? We don’t know that, and so I think that is an unknown question.”

For now, the healthcare professionals who have been put in the position of saying “no” to prescribing ivermectin are waiting for the data from the U.S. trials. Dr. Rani Sebti, an infectious-disease physician at Hackensack Meridian Health hospital system in New Jersey, says he’s been fielding calls from primary-care doctors in the U.S. and abroad about whether to prescribe ivermectin when patients ask for it.

“I cannot sit here and tell you ivermectin is the worst drug in the world,” he said. “I need to see a good prospective, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. And then when we get that study, it will answer the question for good.”

Good data on ivermectin coming soon

Sometime this winter or early spring, a randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind trial sponsored by the National Institutes of Health that is testing ivermectin in 1,000 patients is expected to produce results, says Dr. Susanna Naggie, the vice dean for clinical research at Duke University’s medical school and the researcher running the trial.

The University of Minnesota’s randomized study has enrolled 1,196 participants, one-third of whom received ivermectin. (Both trials are evaluating several repurposed drugs as possible COVID-19 treatments.) Within the next few weeks, the Minnesota institution is expected to share the first findings from the ivermectin part of its trial, nearly two years after the first preprint examining ivermectin’s viability was published.

In pandemic time, this may feel overly slow, but, for the scientists conducting these trials, it’s still a pretty quick turnaround. The experts I spoke to seem to think that ivermectin could demonstrate a small benefit for some COVID-19 patients, but none think it’s likely that it will produce any of the major benefits promised by the fraudulent trials.

Edward Mills, a health-sciences professor at Canada’s McMaster University, is co-investigator of the Together clinical trial, another rigorous study that is evaluating nine different repurposed drugs as COVID-19 therapies, including ivermectin. It recently completed the ivermectin analysis but found it “did not demonstrate an important benefit,” Mills said in an email. The research may be published this month, he said.

Nevertheless, there is an idea circulating among scientists like Mills that ivermectin may be more likely to benefit COVID-19 patients in areas of the world with a high prevalence of parasitic worms. “What is possible is that co-infection of parasites with COVID may worsen health outcomes,” Mills said.

This is an idea also raised by Boulware, the scientist working on the University of Minnesota’s ivermectin study. Corticosteroids, like dexamethasone, are now considered the standard of care for severely ill COVID-19 patients; however, these drugs can cause what is called a “hyperinfection” and sometimes be fatal in a patient who has a parasitic infection. It’s possible that additional data about ivermectin gathered from different patient populations could show the drug being more beneficial in people who live in parasitic regions of the world, they say.

However, most native-born Americans don’t have parasites. And, since 2005, the U.S. policy has been to recommend that refugees from Africa, Asia, the Middle East, Latin America and the Caribbean receive treatment or presumptive antiparasitic treatment — including ivermectin — before arriving in the U.S.

“In certain patient populations, if you have a parasitic infection, it certainly can be beneficial if you’re giving steroids,” Boulware said. “Does that mean [as an] outpatient-setting early therapy in the U.S. that there’s a benefit? We don’t know that, and so I think that is an unknown question.”

For now, the healthcare professionals who have been put in the position of saying “no” to prescribing ivermectin are waiting for the data from the U.S. trials. Dr. Rani Sebti, an infectious-disease physician at Hackensack Meridian Health hospital system in New Jersey, says he’s been fielding calls from primary-care doctors in the U.S. and abroad about whether to prescribe ivermectin when patients ask for it.

“I cannot sit here and tell you ivermectin is the worst drug in the world,” he said. “I need to see a good prospective, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. And then when we get that study, it will answer the question for good.”