A global web of patent laws protects Big Pharma

Why no generic insulin?

Scientists working in Canada’s public sector discovered insulin nearly a century ago. The first techniques for synthesizing the compound, which should have more readily allowed for the production of generic versions, emerged some four decades ago. Yet today insulin remains unavailable in any significant generic version.

One of the three companies that control 90% of the world insulin market, Eli Lilly, recently did bow to public pressure by announcing a forthcoming “authorized generic” version called Lispro. But that could still run some people $140 per prescription.

U.S. consumers are not alone in facing high prices of insulin and other life-saving drugs. For the last two decades, intense controversy has raged around multinational pharmaceutical giants being able to monopolize access to vital medicines the world over. A key means of doing so is through the legal power of patents, and the monopoly-like profits – or what some experts call unearned economic rents – they guarantee.

Think of rent as a windfall gained for making little effort of one’s own. Being “unearned,” rents are thus usually distinguished from ordinary business profits. In this way, they are comparable to the fees a medieval lord would charge for access to cropland on a vast estate.

To fully explain the problem of economic rents and access to medicines, however, we need to look still further: to the controversies that have swirled around pharmaceutical patents in countries far less wealthy than the U.S.

A worldwide problem, but hidden from sight

For more than 20 years, in various parts of Africa, Asia and Latin America, countries have been battling a global system of rent-taking, or “rentierism” for short, that disproportionately benefits Big Pharma.

This state of affairs could not exist without the government officials whom Big Pharma has lobbied successfully in wealthy countries. Patents and other intellectual property rights allow the multinationals to capture rent by evading competition for years on end.

This global battle around pharmaceutical patents began in earnest with the founding of the World Trade Organization(WTO) in 1994. This included an annex agreement on intellectual property rights known as the Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights.

Many countries already allowed for patents before 1994, but only on “processes” of manufacture or synthesis. After 1994, WTO member countries were required to extend patents to the vital end products of such processes as well.

For inhabitants of developing countries, whose greatest public health problems at the time derived from diseases like malaria, tuberculosis and HIV-AIDS, this crystallized various questions of great import. Should the agreements enable Big Pharma’s monopoly-like patent rights to trump the ability of the sick and dying to obtain generic versions of life savings medicines? And if so, to what extent?

By 2001, all WTO member states officially had conceded the rights of developing countries to take measures to increase access to lifesaving medicines. But Big Pharma and its allies have never relented in pressing for more, not less, stringent intellectual property protections around the world.

Shaky justifications

Since 1994, Big Pharma has imposed ever more severe requirements around patent rights. They have insisted that patent rights are necessary to “incentivize” the availability of drugs for conditions like tuberculosis and malaria that, having no markets in the developed world, require guaranteed premiums from whatever countries they are sold in.

Yet for just as long, critics have alleged that Big Pharma typically uses inflated, misleading or otherwise opaque cost data to tout the billions of dollars it claims to spend on drug development. Likewise, critics have continuously called attention to the way that most drug development is built on publicly funded research.

And, finally, critics have never stopped highlighting the fact that Big Pharma long ago largely abandoned research and development for drugs for infectious ailments in developing nations, and increasingly switched to spending on blockbuster noninfectious disease drugs.

Yet as diseases such as cancer and heart disease begin to take an even greater toll in the developing world, patents will extract an ever greater toll on patient populations across the world.

In a developing world where public health problems increasingly look similar to the developed world’s, in fact, multinational pharmaceutical corporations could become better – not worse – placed to expand their profits by tapping new markets for drugs like insulin and beta blockers.

A convergence between the sick across the globe

One unexpected lesson from this is that ordinary people around the world will increasingly find themselves in the same boat when it comes to accessing the medicines they need.

Therefore, if countries in the developing world are forced to give up the fight against patent rentierism, it should be a concern both to their own residents and to residents of wealthy countries too.

Just this past September, for example, Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi signaled that his country – which has a robust generic drugs industry that supplies low-cost medicines to people around the world – was ready to concede to the demands of Big Pharma by moving toward abdicating his country’s vital role as “the pharmacy of the world.” India has now signed an interim trade agreement with the Trump administration that will require it to more strictly enforce the patent rights of pharmaceutical multinationals, with the latest news reports indicating it may even now be finalized.

Over the course of the current battle for the Democratic nomination, many will have heard about the plight of residents of Michigan who are left asking how insulin costs 10 times in the U.S. what it costs 10 minutes away across our northern border.

Given the larger conversation about patent rents and access to medicines that we should be having, however, it behooves those of us who live in places like the U.S. to look not only to Canada but to what is happening around the world, where the sick and dying face increasingly similar ailments – and fights – as our own.

January 28, 2020 Faisal Chaudhry

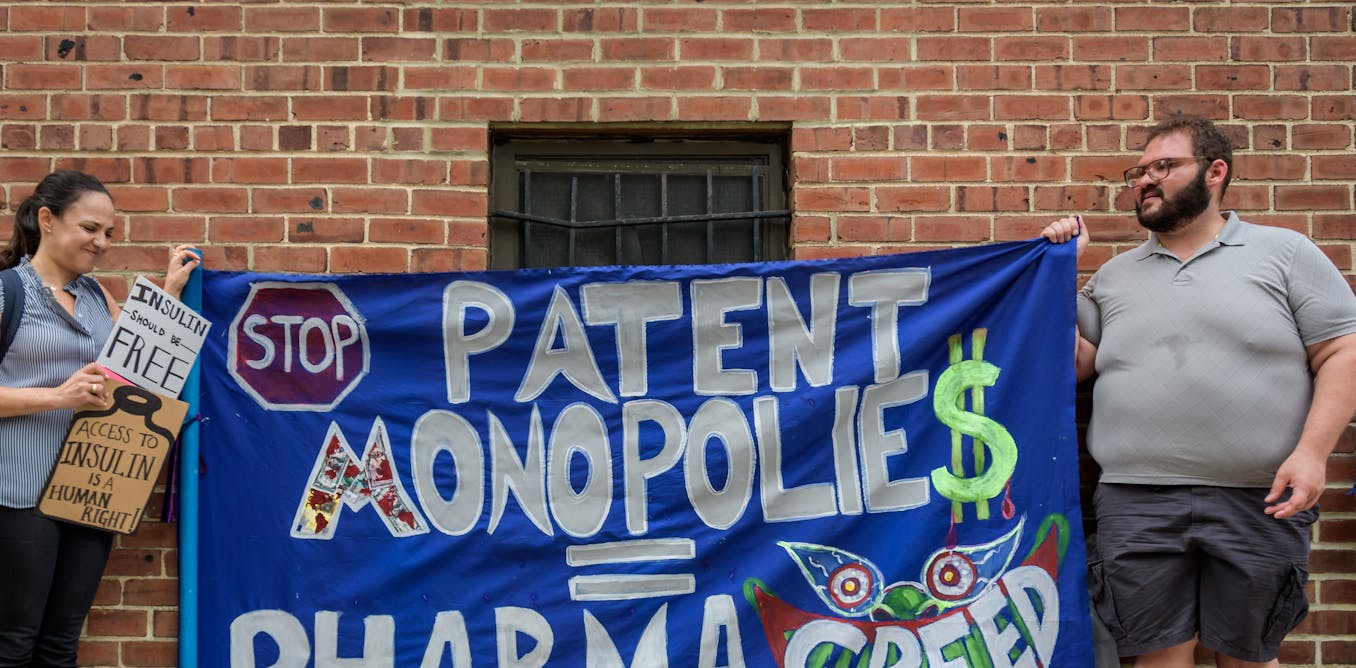

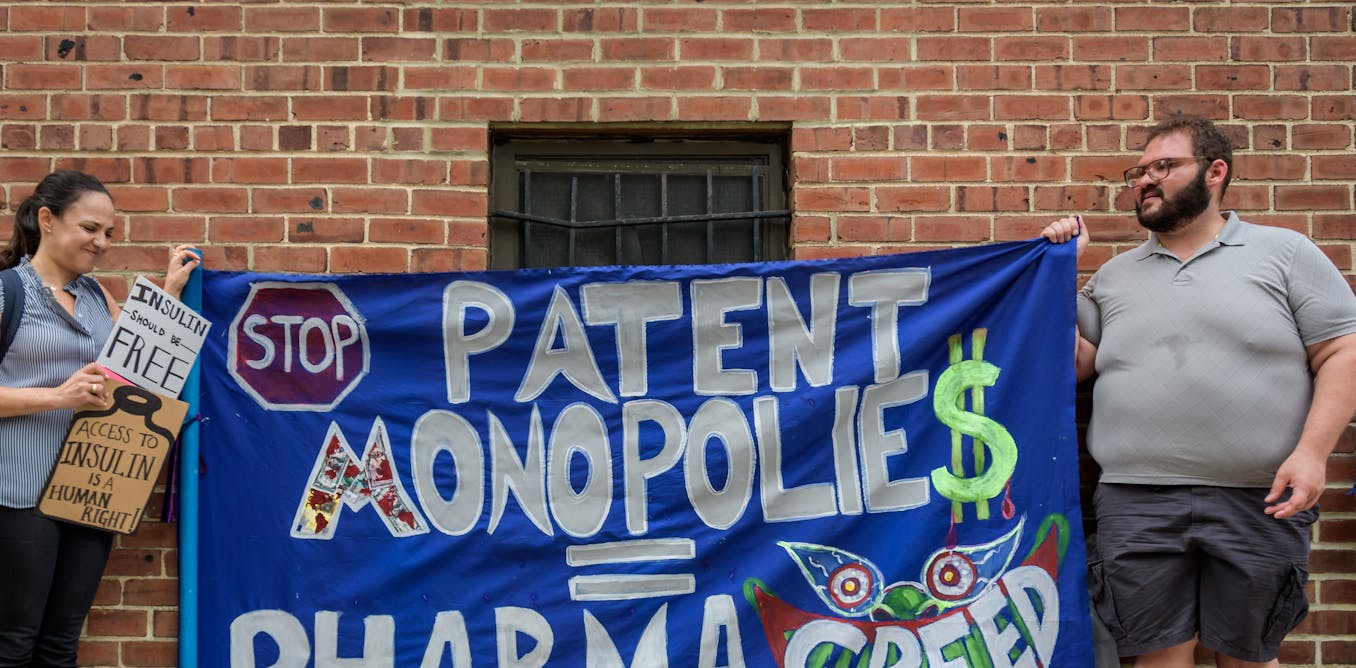

Advocates for lower drug prices held a vigil on Sept. 5, 2019 outside of Eli Lilly in New York City, honoring those who have lost their lives due to the high cost of insulin. Eric McGregor/LightRocket via Getty Images

The high price of insulin, which has reached as much as US$450 per month, has raised outrage across the country. Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-Vt.) has called it a national embarrassment, wondering why U.S. residents should have to drive to Canada to buy cheaper insulin.

As a legal scholar who focuses on the contradictory role of property rights on economic well-being, including through the role of intellectual property rights, my research makes it clear that drug pricing is far more complicated than any candidate on the debate stage has time to explain.

To fully understand these complexities requires looking at a web of international patent law and trade agreements.

Advocates for lower drug prices held a vigil on Sept. 5, 2019 outside of Eli Lilly in New York City, honoring those who have lost their lives due to the high cost of insulin. Eric McGregor/LightRocket via Getty Images

The high price of insulin, which has reached as much as US$450 per month, has raised outrage across the country. Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-Vt.) has called it a national embarrassment, wondering why U.S. residents should have to drive to Canada to buy cheaper insulin.

As a legal scholar who focuses on the contradictory role of property rights on economic well-being, including through the role of intellectual property rights, my research makes it clear that drug pricing is far more complicated than any candidate on the debate stage has time to explain.

To fully understand these complexities requires looking at a web of international patent law and trade agreements.

Insulin was discovered almost 100 years ago, saving the lives of many people with diabetes. Its soaring costs in recent years has brought outcries from patients and politicians. John Fredricks/NurPhoto via Getty Images

Why no generic insulin?

Scientists working in Canada’s public sector discovered insulin nearly a century ago. The first techniques for synthesizing the compound, which should have more readily allowed for the production of generic versions, emerged some four decades ago. Yet today insulin remains unavailable in any significant generic version.

One of the three companies that control 90% of the world insulin market, Eli Lilly, recently did bow to public pressure by announcing a forthcoming “authorized generic” version called Lispro. But that could still run some people $140 per prescription.

U.S. consumers are not alone in facing high prices of insulin and other life-saving drugs. For the last two decades, intense controversy has raged around multinational pharmaceutical giants being able to monopolize access to vital medicines the world over. A key means of doing so is through the legal power of patents, and the monopoly-like profits – or what some experts call unearned economic rents – they guarantee.

Think of rent as a windfall gained for making little effort of one’s own. Being “unearned,” rents are thus usually distinguished from ordinary business profits. In this way, they are comparable to the fees a medieval lord would charge for access to cropland on a vast estate.

To fully explain the problem of economic rents and access to medicines, however, we need to look still further: to the controversies that have swirled around pharmaceutical patents in countries far less wealthy than the U.S.

A worldwide problem, but hidden from sight

For more than 20 years, in various parts of Africa, Asia and Latin America, countries have been battling a global system of rent-taking, or “rentierism” for short, that disproportionately benefits Big Pharma.

This state of affairs could not exist without the government officials whom Big Pharma has lobbied successfully in wealthy countries. Patents and other intellectual property rights allow the multinationals to capture rent by evading competition for years on end.

This global battle around pharmaceutical patents began in earnest with the founding of the World Trade Organization(WTO) in 1994. This included an annex agreement on intellectual property rights known as the Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights.

Many countries already allowed for patents before 1994, but only on “processes” of manufacture or synthesis. After 1994, WTO member countries were required to extend patents to the vital end products of such processes as well.

For inhabitants of developing countries, whose greatest public health problems at the time derived from diseases like malaria, tuberculosis and HIV-AIDS, this crystallized various questions of great import. Should the agreements enable Big Pharma’s monopoly-like patent rights to trump the ability of the sick and dying to obtain generic versions of life savings medicines? And if so, to what extent?

By 2001, all WTO member states officially had conceded the rights of developing countries to take measures to increase access to lifesaving medicines. But Big Pharma and its allies have never relented in pressing for more, not less, stringent intellectual property protections around the world.

Shaky justifications

Since 1994, Big Pharma has imposed ever more severe requirements around patent rights. They have insisted that patent rights are necessary to “incentivize” the availability of drugs for conditions like tuberculosis and malaria that, having no markets in the developed world, require guaranteed premiums from whatever countries they are sold in.

Yet for just as long, critics have alleged that Big Pharma typically uses inflated, misleading or otherwise opaque cost data to tout the billions of dollars it claims to spend on drug development. Likewise, critics have continuously called attention to the way that most drug development is built on publicly funded research.

And, finally, critics have never stopped highlighting the fact that Big Pharma long ago largely abandoned research and development for drugs for infectious ailments in developing nations, and increasingly switched to spending on blockbuster noninfectious disease drugs.

Yet as diseases such as cancer and heart disease begin to take an even greater toll in the developing world, patents will extract an ever greater toll on patient populations across the world.

In a developing world where public health problems increasingly look similar to the developed world’s, in fact, multinational pharmaceutical corporations could become better – not worse – placed to expand their profits by tapping new markets for drugs like insulin and beta blockers.

A convergence between the sick across the globe

One unexpected lesson from this is that ordinary people around the world will increasingly find themselves in the same boat when it comes to accessing the medicines they need.

Therefore, if countries in the developing world are forced to give up the fight against patent rentierism, it should be a concern both to their own residents and to residents of wealthy countries too.

Just this past September, for example, Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi signaled that his country – which has a robust generic drugs industry that supplies low-cost medicines to people around the world – was ready to concede to the demands of Big Pharma by moving toward abdicating his country’s vital role as “the pharmacy of the world.” India has now signed an interim trade agreement with the Trump administration that will require it to more strictly enforce the patent rights of pharmaceutical multinationals, with the latest news reports indicating it may even now be finalized.

Over the course of the current battle for the Democratic nomination, many will have heard about the plight of residents of Michigan who are left asking how insulin costs 10 times in the U.S. what it costs 10 minutes away across our northern border.

Given the larger conversation about patent rents and access to medicines that we should be having, however, it behooves those of us who live in places like the U.S. to look not only to Canada but to what is happening around the world, where the sick and dying face increasingly similar ailments – and fights – as our own.

Author

Faisal Chaudhry

Professor of Law, University of Dayton

Disclosure statement

Faisal Chaudhry has received funding from the Mellon Foundation, the American Council of Learned Societies, the Fulbright Program of the Bureau of Educational and Cultural Affairs of the United States Department of State and Harvard University.

Partners

Professor of Law, University of Dayton

Disclosure statement

Faisal Chaudhry has received funding from the Mellon Foundation, the American Council of Learned Societies, the Fulbright Program of the Bureau of Educational and Cultural Affairs of the United States Department of State and Harvard University.

Partners

No comments:

Post a Comment