Matthias Gafni Jan. 11, 2020

1of5

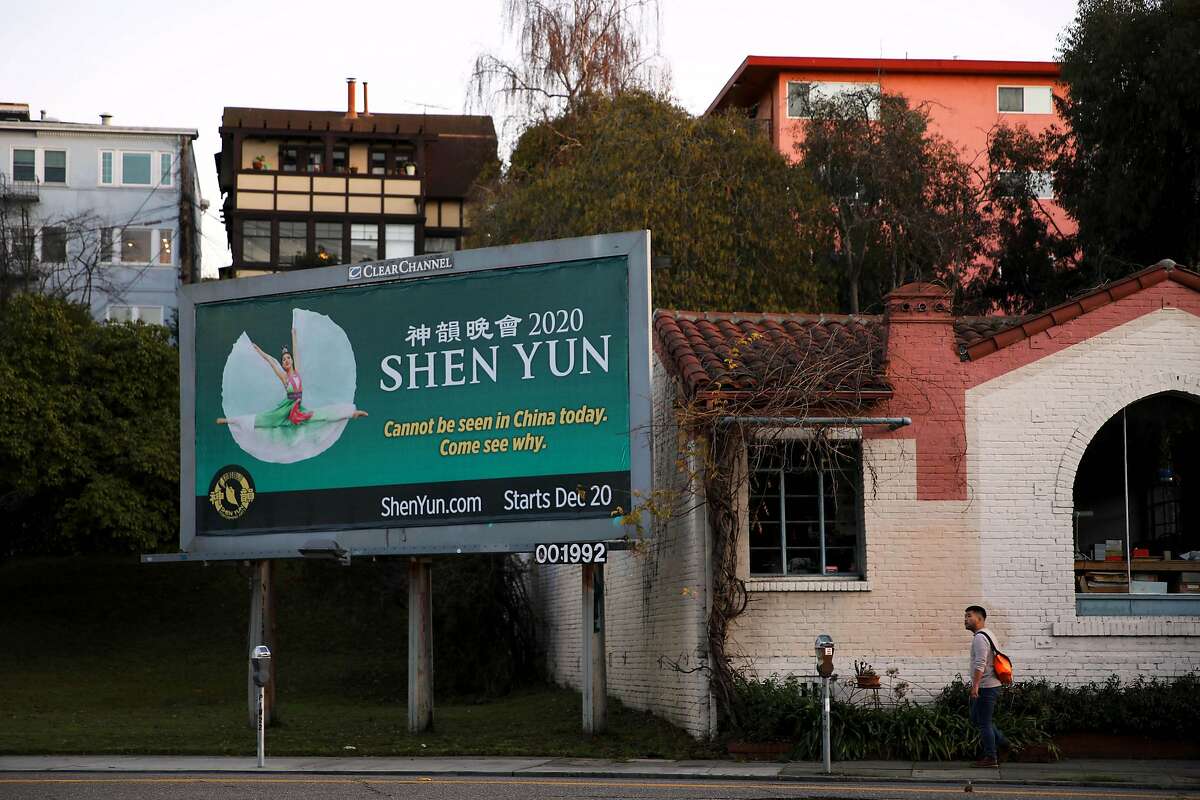

A man walks near a Shen Yun billboard as he approaches

Park Blvd. and East 20th Street, in Oakland, Calif., on

Tuesday, January 7, 2020.

Photo: Yalonda M. James, The Chronicle

2of5

A Shen Yun ad and poster are seen on the outside of the

San Jose Center for the Performing Arts on Tuesday,

January 7, 2020 in San Jose, Calif.Photo: Lea Suzuki,

The Chronicle

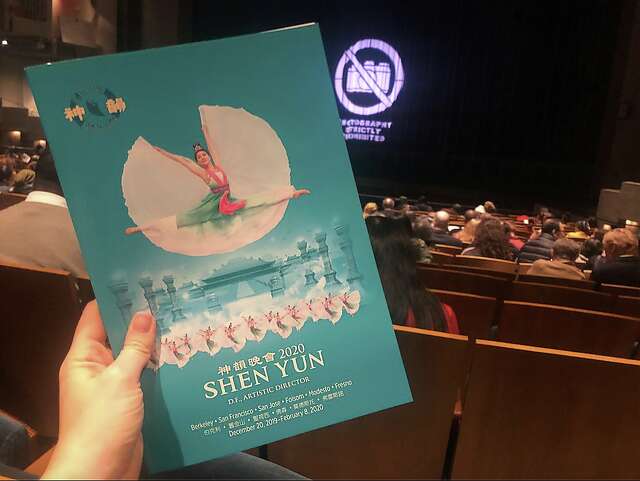

A smiling young woman flying through the air, her legs splayed at a perfect 180 degrees as she reaches her arms skyward, unveiling a nearly full circle of white fabric

It’s “Shen Yun” season and if your heart circulates blood you’ve seen an advertisement promising “5,000 years of civilization reborn.” In the Bay Area and across many parts of the world, Shen Yun ads are as ubiquitous as 1-877-Kars4Kids radio jingles as they encourage people to shell out for tickets to see the dance troupe and symphony that — to the surprise of some viewers — promote the spiritual movement called Falun Gong, also known as Falun Dafa.

If it seems practitioners of Falun Gong, which is locked in a bitter political battle with the communist government of China, spend a lot on publicity for the show, well, they do.

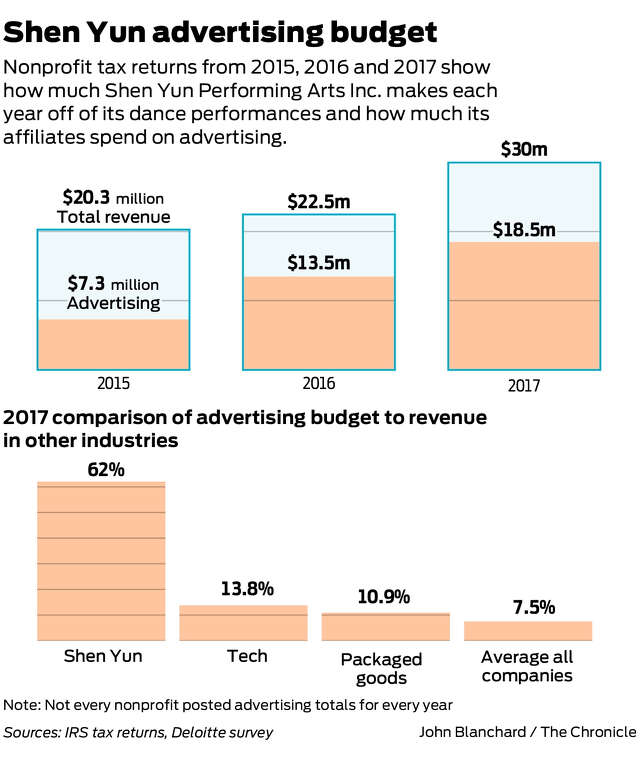

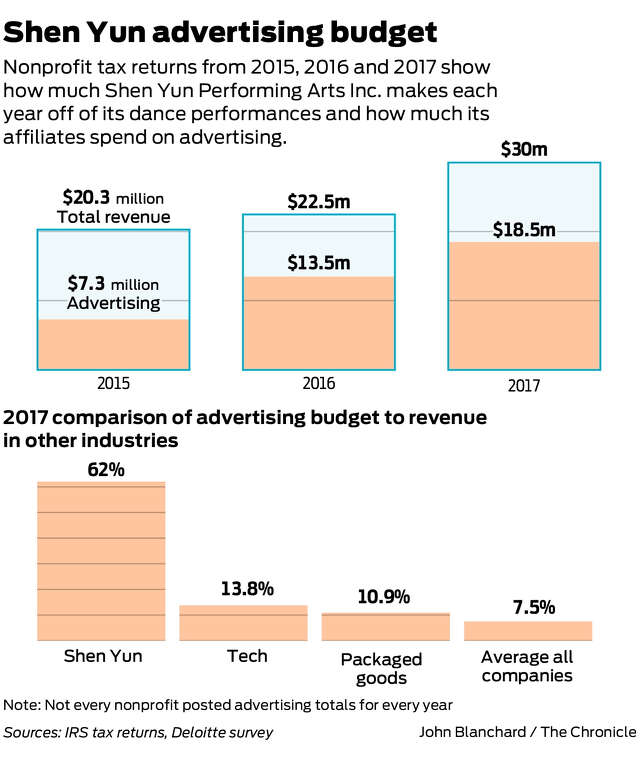

Shen Yun-linked nonprofit groups spent at least $39.3 million on advertising across the country from 2015 to 2017, according to a Chronicle review of three years of federal tax returns, the most recent made public. It’s possible the spending has gone up since, and that the records analyzed do not account for all of the spending on publicity for Shen Yun.

Over those three years, Shen Yun Performing Arts Inc., based in Cuddebackville, N.Y., reported revenue of $72.8 million, largely from ticket sales for shows performed in various cities by one of the dance company’s traveling troupes. The outfit just finished up a run of shows in San Francisco and has upcoming performances in San Jose, Berkeley, Modesto and Fresno.

Shen Yun Performing Arts spent $47.2 million in those three years, according to tax returns, putting on its shows that accuse the Chinese Communist party of persecuting Falun Gong adherents. That has helped the nonprofit boost its assets from $61 million to $95.7 million by the end of 2017.

In San Francisco and the Bay Area, the shows are run by the San Francisco Falun Buddha Study Association, which lists as its mission: “Foster the universal principles and values of ‘truthful, compassion and tolerant’ through various forms including Falun Dafa (Falun Gong) studies, exercises and experience-sharing activities.”

A Shen Yun billboard in the 900 block of Mission St. in

Matthias Gafni joined The San Francisco Chronicle as an enterprise reporter in February 2019. He investigates stories in the East Bay and beyond. For almost two decades, Gafni worked for the Bay Area News Group – San Jose Mercury News, East Bay Times and Vallejo Times-Herald -- covering corruption, child sexual abuse, criminal justice, aviation and more. He was born and raised in the Bay Area and graduated from UC Davis. He lives with his wife and three kids in the East Bay.

3of5Shen Yun advertisement at 6th and Folsom in San Francisco,

Calif., on Tuesday, January 7, 2020.

Photo: Scott Strazzante, The Chronicle

The image is likely hanging on your doorknob as you read this. And popping up on your Facebook feed. When you glance up from your phone, there it is again — on a billboard, a bus or the wall of a BART platform

The image is likely hanging on your doorknob as you read this. And popping up on your Facebook feed. When you glance up from your phone, there it is again — on a billboard, a bus or the wall of a BART platform

A smiling young woman flying through the air, her legs splayed at a perfect 180 degrees as she reaches her arms skyward, unveiling a nearly full circle of white fabric

It’s “Shen Yun” season and if your heart circulates blood you’ve seen an advertisement promising “5,000 years of civilization reborn.” In the Bay Area and across many parts of the world, Shen Yun ads are as ubiquitous as 1-877-Kars4Kids radio jingles as they encourage people to shell out for tickets to see the dance troupe and symphony that — to the surprise of some viewers — promote the spiritual movement called Falun Gong, also known as Falun Dafa.

If it seems practitioners of Falun Gong, which is locked in a bitter political battle with the communist government of China, spend a lot on publicity for the show, well, they do.

Shen Yun-linked nonprofit groups spent at least $39.3 million on advertising across the country from 2015 to 2017, according to a Chronicle review of three years of federal tax returns, the most recent made public. It’s possible the spending has gone up since, and that the records analyzed do not account for all of the spending on publicity for Shen Yun.

Over those three years, Shen Yun Performing Arts Inc., based in Cuddebackville, N.Y., reported revenue of $72.8 million, largely from ticket sales for shows performed in various cities by one of the dance company’s traveling troupes. The outfit just finished up a run of shows in San Francisco and has upcoming performances in San Jose, Berkeley, Modesto and Fresno.

Shen Yun Performing Arts spent $47.2 million in those three years, according to tax returns, putting on its shows that accuse the Chinese Communist party of persecuting Falun Gong adherents. That has helped the nonprofit boost its assets from $61 million to $95.7 million by the end of 2017.

In San Francisco and the Bay Area, the shows are run by the San Francisco Falun Buddha Study Association, which lists as its mission: “Foster the universal principles and values of ‘truthful, compassion and tolerant’ through various forms including Falun Dafa (Falun Gong) studies, exercises and experience-sharing activities.”

Such nonprofit organizations are required by law to release their tax returns. The Chronicle’s review of ad spending looked at more than 30 groups, most of whom posted three years of records. Shen Yun Performing Arts itself spends no money on advertising, instead relying on the smaller Falun Dafa nonprofits, based out of regions across the country, to promote the shows in their areas.

In 2017, the San Francisco nonprofit group reported $3.9 million in ticket sales, while spending $2.2 million on advertising and promotion.

In general, spending such a high percentage of expected revenue on marketing “just defies logic,” said Bill Pearce, assistant dean of UC Berkeley’s Haas School of Business and its chief marketing officer.

“Typically, if you’re higher than 10% it’s really high,” he said, noting that the industry benchmark for ad spending is 7.5% of projected revenue. “It’s truly from a marketing standpoint what we call a ‘heavy-up.’ ”

Shen Yun’s finances seem to pencil out, Pearce said, thanks to the work of volunteers. The San Francisco Falun Gong group reported having 100 volunteers, while the international theater company had another 211, according to the 2017 tax returns. Each regional nonprofit operates on a completely volunteer workforce.

The theater company reported paying 192 employees a total of $5.9 million in 2017, meaning dancers and other paid workers made less than $30,000 on average.

A Shen Yun ad is seen on the side of a bus traveling down

In 2017, the San Francisco nonprofit group reported $3.9 million in ticket sales, while spending $2.2 million on advertising and promotion.

In general, spending such a high percentage of expected revenue on marketing “just defies logic,” said Bill Pearce, assistant dean of UC Berkeley’s Haas School of Business and its chief marketing officer.

“Typically, if you’re higher than 10% it’s really high,” he said, noting that the industry benchmark for ad spending is 7.5% of projected revenue. “It’s truly from a marketing standpoint what we call a ‘heavy-up.’ ”

Shen Yun’s finances seem to pencil out, Pearce said, thanks to the work of volunteers. The San Francisco Falun Gong group reported having 100 volunteers, while the international theater company had another 211, according to the 2017 tax returns. Each regional nonprofit operates on a completely volunteer workforce.

The theater company reported paying 192 employees a total of $5.9 million in 2017, meaning dancers and other paid workers made less than $30,000 on average.

A Shen Yun ad is seen on the side of a bus traveling down

Santa Clara Street on Tuesday, January 7, 2020 in San Jose,

Calif. Photo: Lea Suzuki, The Chronicle

Another financial benefit: Falun Gong is linked to the Epoch Times and Epoch Media Group, news organizations founded by practitioners that provide an outlet to handle printing, direct mail and other marketing needs for Shen Yun, according to tax returns.

The Epoch Times, which in recent years has been criticized for supporting far-right conspiracy theories, prominently features stories about Shen Yun. An article on the website dated Friday carried the headline, “Corporate Leaders Applaud Shen Yun’s Beautiful Stories of Integrity.”

Officials at Shen Yun Performing Arts headquarters did not respond to a request for comment, but one of the volunteers at the San Francisco nonprofit spoke to The Chronicle.

David Zhang, a software engineer who has practiced Falun Gong for 16 years, helps promote performances in the Bay Area. The mass advertising is only possible because he and other followers give their time, Zhang said, emphasizing he spoke for himself and not the entire nonprofit.

“I don’t dance or sing, I just do my best to help and do it from the bottom of my heart,” he said. “We’re facing an incredible challenge and we want to get the word out. We’re facing incredible repression.”

Shen Yun was formed in 2006 by followers of Falun Gong, which Li Hongzhi had founded in China in 1992 and drew on the tradition of qigong, in which breathing, meditation and movement foster good health or spiritual enlightenment.

Li drew attention for voicing strange beliefs, including saying in a 1999 interview with Time magazine that “aliens have begun to invade the human mind and its ideology and culture.” But Falun Gong has fought allegations that it is a cult from Chinese authorities, and journalists and researchers who have written about the movement say it has no record of using abuse or coercion.

The Chinese government banned Falun Gong in 1999, and in recent years the embassy in the U.S. has not shied from striking against Shen Yun — and its organizers.

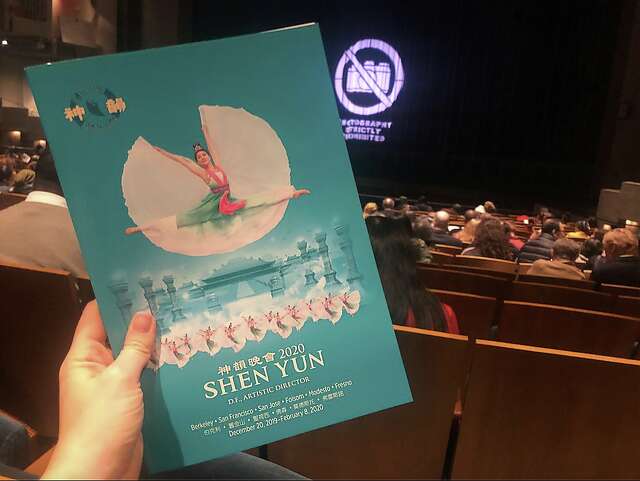

Before the show started at a Dec. 20, 2019 performance

Another financial benefit: Falun Gong is linked to the Epoch Times and Epoch Media Group, news organizations founded by practitioners that provide an outlet to handle printing, direct mail and other marketing needs for Shen Yun, according to tax returns.

The Epoch Times, which in recent years has been criticized for supporting far-right conspiracy theories, prominently features stories about Shen Yun. An article on the website dated Friday carried the headline, “Corporate Leaders Applaud Shen Yun’s Beautiful Stories of Integrity.”

Officials at Shen Yun Performing Arts headquarters did not respond to a request for comment, but one of the volunteers at the San Francisco nonprofit spoke to The Chronicle.

David Zhang, a software engineer who has practiced Falun Gong for 16 years, helps promote performances in the Bay Area. The mass advertising is only possible because he and other followers give their time, Zhang said, emphasizing he spoke for himself and not the entire nonprofit.

“I don’t dance or sing, I just do my best to help and do it from the bottom of my heart,” he said. “We’re facing an incredible challenge and we want to get the word out. We’re facing incredible repression.”

Shen Yun was formed in 2006 by followers of Falun Gong, which Li Hongzhi had founded in China in 1992 and drew on the tradition of qigong, in which breathing, meditation and movement foster good health or spiritual enlightenment.

Li drew attention for voicing strange beliefs, including saying in a 1999 interview with Time magazine that “aliens have begun to invade the human mind and its ideology and culture.” But Falun Gong has fought allegations that it is a cult from Chinese authorities, and journalists and researchers who have written about the movement say it has no record of using abuse or coercion.

The Chinese government banned Falun Gong in 1999, and in recent years the embassy in the U.S. has not shied from striking against Shen Yun — and its organizers.

Before the show started at a Dec. 20, 2019 performance

of Shen Yun at Zellerbach Hall in Berkeley.

Photo: Alix Martichoux, SFGATE

“Clearly, the so-called ‘Shen Yun’ is not a cultural performance at all but a political tool of ‘Falun Gong’ to preach cult messages, spread anti-China propaganda, increase its own influence and raise fund(s),” the embassy states on its website. “(The) show denigrates and distorts the Chinese culture, and deceives, makes fool of and even brings harm to the audience.”

On its own website, Shen Yun leaders state, “While Falun Dafa practitioners in China continue to face horrific abuse, the Party has been extending its persecution outside of China. This includes harassing Shen Yun.”

Shen Yun means the “beauty of divine beings dancing,” and has six companies touring the world, claiming to perform in more than 150 theaters every year.

The show is a “soft approach in trying to interest people in their practices and win people over,” said David Bachman, an international studies professor at the University of Washington who specializes in Chinese politics. He said he often sees students handing out Shen Yun fliers on campus.

In a particularly detailed tax return, the Greater Philadelphia Falun Dafa Association offered a peek inside its operation of 55 volunteers. In 2017, Shen Yun put on 23 shows in Philadelphia and Pittsburgh, gaining almost 31,000 attendees and almost $2.8 million in ticket sales.

The group spent $1.4 million in advertising that year, paying an Illinois company $500,000 for direct mailing and a Dallas television station $200,000 for ads. It also paid $320,000 to two companies linked to Falun Gong for direct mailing and online ads, according to its tax return.

Photo: Alix Martichoux, SFGATE

“Clearly, the so-called ‘Shen Yun’ is not a cultural performance at all but a political tool of ‘Falun Gong’ to preach cult messages, spread anti-China propaganda, increase its own influence and raise fund(s),” the embassy states on its website. “(The) show denigrates and distorts the Chinese culture, and deceives, makes fool of and even brings harm to the audience.”

On its own website, Shen Yun leaders state, “While Falun Dafa practitioners in China continue to face horrific abuse, the Party has been extending its persecution outside of China. This includes harassing Shen Yun.”

Shen Yun means the “beauty of divine beings dancing,” and has six companies touring the world, claiming to perform in more than 150 theaters every year.

The show is a “soft approach in trying to interest people in their practices and win people over,” said David Bachman, an international studies professor at the University of Washington who specializes in Chinese politics. He said he often sees students handing out Shen Yun fliers on campus.

In a particularly detailed tax return, the Greater Philadelphia Falun Dafa Association offered a peek inside its operation of 55 volunteers. In 2017, Shen Yun put on 23 shows in Philadelphia and Pittsburgh, gaining almost 31,000 attendees and almost $2.8 million in ticket sales.

The group spent $1.4 million in advertising that year, paying an Illinois company $500,000 for direct mailing and a Dallas television station $200,000 for ads. It also paid $320,000 to two companies linked to Falun Gong for direct mailing and online ads, according to its tax return.

A Shen Yun billboard in the 900 block of Mission St. in

San Francisco, Calif., on Tuesday, January 7, 2020.

Photo: Yalonda M. James, The Chronicle

Pearce, the Berkeley marketer, called the advertising blitz “omnipresent,” an approach that can backfire.

“There’s always a risk that if your message is seen too many times consumers will tune it out,” he said. “I think you can go past building a brand and you start building a meme.”

Zhang said that while volunteers are not marketing experts, they feel the publicity is effective.

“It’s working good. It’s getting a lot of people to the performances. Most of the shows sold out,” Zhang said. “That’s the goal of marketing. It’s not necessarily a bad thing.”

Matthias Gafni is a San Francisco Chronicle staff writer. Email: matthias.gafni@sfchronicle.com Twitter: @mgafni

Matthias Gafni

Follow Matthias on:https://www.facebook.com/SFChronicle/mgafni

Photo: Yalonda M. James, The Chronicle

Pearce, the Berkeley marketer, called the advertising blitz “omnipresent,” an approach that can backfire.

“There’s always a risk that if your message is seen too many times consumers will tune it out,” he said. “I think you can go past building a brand and you start building a meme.”

Zhang said that while volunteers are not marketing experts, they feel the publicity is effective.

“It’s working good. It’s getting a lot of people to the performances. Most of the shows sold out,” Zhang said. “That’s the goal of marketing. It’s not necessarily a bad thing.”

Matthias Gafni is a San Francisco Chronicle staff writer. Email: matthias.gafni@sfchronicle.com Twitter: @mgafni

Matthias Gafni

Follow Matthias on:https://www.facebook.com/SFChronicle/mgafni

Matthias Gafni joined The San Francisco Chronicle as an enterprise reporter in February 2019. He investigates stories in the East Bay and beyond. For almost two decades, Gafni worked for the Bay Area News Group – San Jose Mercury News, East Bay Times and Vallejo Times-Herald -- covering corruption, child sexual abuse, criminal justice, aviation and more. He was born and raised in the Bay Area and graduated from UC Davis. He lives with his wife and three kids in the East Bay.

No comments:

Post a Comment