A republished version of ‘Chinese Pictures: China Through the Eyes of Isabella Bird’ contains 61 images from across China in the 1890s

The photos from acclaimed British travel writer Bird range from classic architecture to dying men to a tower where poor people left dead babies

Annemarie Evans Published: 22 Feb, 2020

“Chinese Pictures: China Through the Eyes of Isabella Bird” is a memoir of an English woman who travelled through the country in the 1890s and took photos of the people and places she came across. Photo: Isabella Bird/Chinese Pictures/Earnshaw Books

In 1894, a middle-aged British woman, independently wealthy from her work as a travel writer, took a course to learn how to use a camera. She planned to use one while travelling around Asia, in what would be her final trip to the region.

The trip was an opportunity for Isabella Bird to hear and see the rapids of China’s untamed Yangtze River, observe the country’s dainty women with bound feet and relish the architecture of arched bridges, temples and the Forbidden City.

The ailments that had dogged Bird throughout her life, though, would soon become too much for her, and the bearers she hired to carry her large, tripod-mounted camera, albumen plates – used for photography at the time – and chemicals ended up having had to carry her, too.In her extensive and arduous journey, there were no dark rooms to develop her photos. The waters of the Yangtze were used to rinse the photographs she took during her extensive three-year journey around East Asia. They were published, on her return to England, in 1900 in Chinese Pictures: China Through the Eyes of Isabella Bird. She died in bed in 1904.

Isabella Bird took many photos during her three-year journey around East Asia.

Bird was a solo traveller at a time when it was thought unusual for a Caucasian woman to travel without a companion. She had been married to a doctor named John Bishop, and she did not remarry after he died in 1886.

Her observations of America, Hawaii, Korea, Japan, China and then-Malaya (a set of states on the Malay Peninsula and Singapore) made her a literary success in England and opened people’s eyes and minds to these faraway countries.

Some 90 years later, Bird’s works were found by a publisher named Graham Earnshaw among a bunch of classic China-related books in a bookshop called Caves in Taipei, Taiwan.

“Forty years ago, I used to buy books from Caves, among them Isabella’s. The first one I read was her Japan story,” Earnshaw says. “She did a very long, interesting trip around Japan and went up near Hokkaido – and it just blew me away. The sense of being with her, the experience of travelling with her, is what makes her writing so brilliant, so extraordinary, so alive.”

Earnshaw has since republished a number of Bird’s works. The layout and organisation of the newer Chinese Pictures, which contains 61 images by Bird, has been kept as close to the original edition as possible, with an additional foreword by Earnshaw.

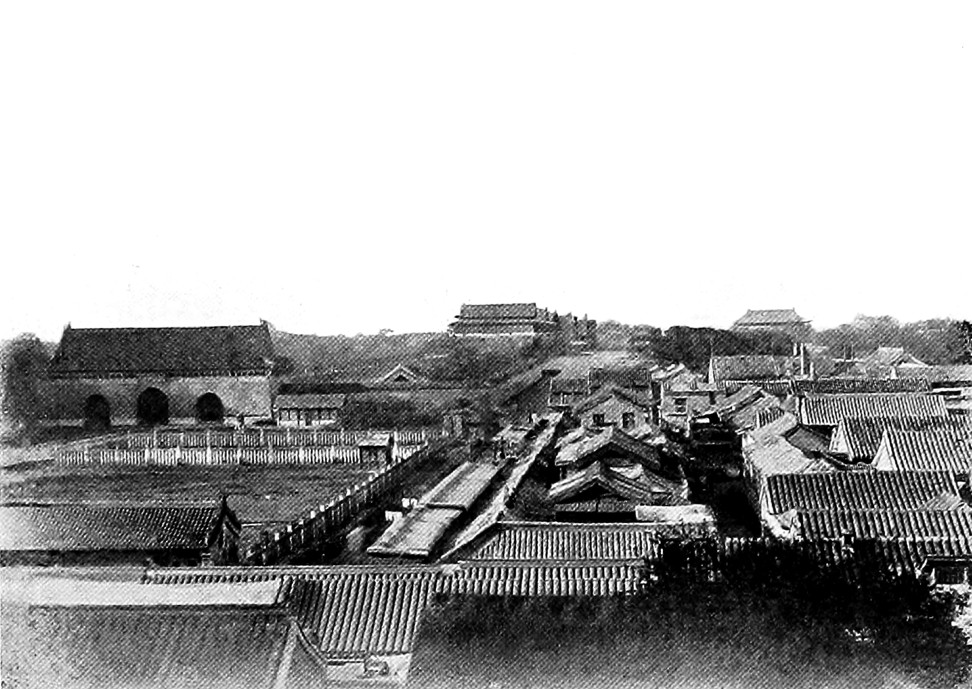

Bird took a photograph of the Forbidden City from the south side from what would be now Tiananmen Square. It shows buildings that no longer exist. Photo: Isabella Bird/Chinese Pictures/Earnshaw Books

“All photos and words in the original are included – not one word [has been] left out,” he says. “We did it because I think anything by Isabella on China is worth keeping in the sun, and these photos are basically unknown and have value in terms of understanding China and Isabella.”

Bird writes about China in The Golden Chersonese and the Way Thither, and The Yangtze Valley and Beyond. On both occasions, she passes through Hong Kong – once during the city’s Great Fire of 1878, where she arrived, dropped her luggage off at the bishop’s house, and went back out to follow the developments of the event.

She also wrote about a court and execution ground in Guangdong province in mainland China’s south, the costumes of Manchurian people in the north, her travels up the Yangtze rapids, and Sichuan and Tibet.

The newer Chinese Pictures contains a foreword by Graham Earnshaw. Photo: Earnshaw Books

“There were a lot of memoirs at that time that looked at things from a military perspective or a cultural perspective, but she was doing it from a humanistic perspective – that is, the people,” Earnshaw says.

“She was paying attention to the people to an extent that I think it was certainly rare for those days, and allowed us to get a sense of not only the places, but the people. She had, of course, various attitudes that come out. We all have our prejudices, but she transcended them to a remarkable extent.”

The China we see through Bird’s eyes in Chinese Pictures is on the cusp of change. It precedes the Boxer Rebellion of 1900, an anti-foreigner uprising, by a few years. Although she was attacked in Chengdu for being a foreigner, she was protected by the men she had hired for her travels, and she remained undeterred on her adventures.

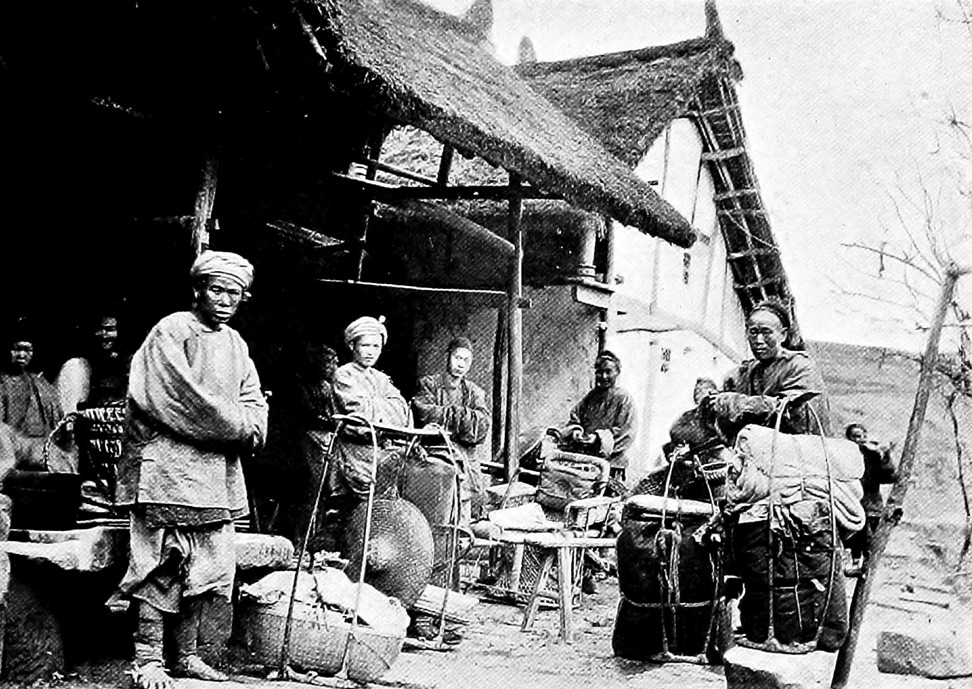

While Isabella Bird often stayed in the homes of missionaries, she also stayed in inns in towns along the route. Photo: Isabella Bird/Chinese Pictures/Earnshaw Books

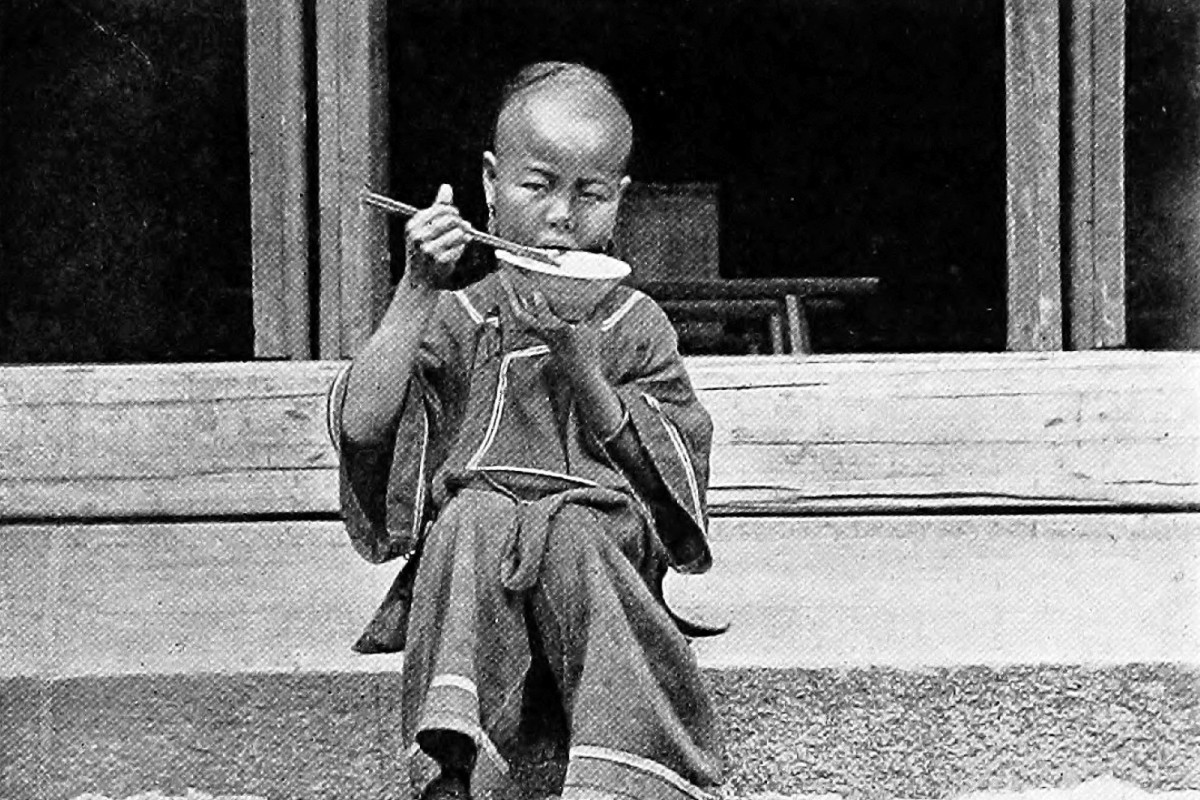

Bird’s photos provide something of a social commentary in the sense that they encapsulate the lives of ordinary Chinese and Manchurians at that time. Although she often stayed in the homes of missionaries, Bird would sometimes stay in town inns, where she was considered an object of curiosity. She photographed people staring at her in one, as well as families on the move in Manchuria, a dying coolie under a tree, and a child eating with chopsticks.

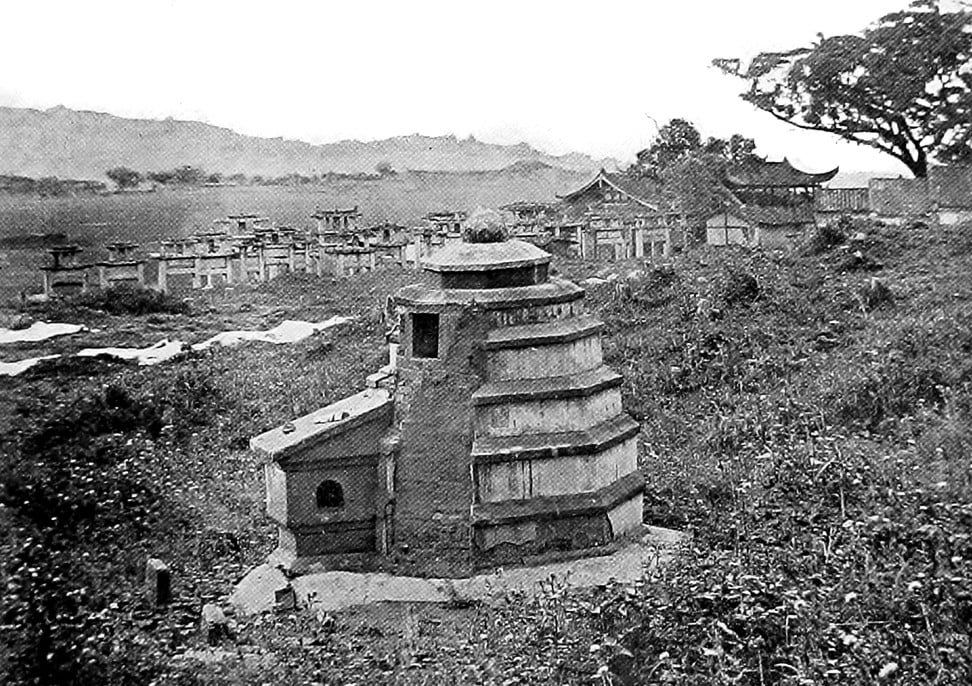

In Fuzhou, she took photos of a “baby tower”, where the bodies of newborn babies were left. These children would have been from parents who were not able to afford another child, were female, or were babies that had simply died from ill health, Earnshaw says.

In Chinese Pictures, the description reads: “When a baby dies and the parents are too poor to give it a decent burial, they drop its poor little body into one of the openings in this tower. A Guild of Benevolence charges itself with the task of clearing out the tower every two to three days, burying the bodies with all religious rites and ceremony.”

A “baby tower”, photographed by Isabella Bird, in Fuzhou, Fujian province. Photo: Isabella Bird/Chinese Pictures/Earnshaw Books

Chinese Pictures doesn’t just have photos of people, though – it has landscape and architectural images, too.

“One of the most interesting photographs is the one that we featured on the cover,” says Earnshaw. “It’s a half-moon bridge at Wanzhou – then called Wanxien, and a key river port on the Yangtze … just on the bend where the Yangtze River heads north to Chongqing and then turns east to go into the gorges and then into the Pacific …

“At that corner is this town, and [Bird] spent quite a lot of time there. The bridge itself was mentioned by a number of other travellers and it was just the most beautiful piece of architecture. Of course, it doesn’t exist any more.”

The bridge of Mien Chuh in Sichuan province. Photo: Courtesy of Isabella Bird/Chinese Pictures/Earnshaw Books

Another photograph shows a child in traditional Chinese clothes eating with chopsticks. Bird’s role as she travelled, says Earnshaw, was that of an observer and she wouldn’t have talked much to the locals – a sentiment that was not uncommon. Foreigners in China were isolated both in terms of local society excluding them and foreigners themselves being unwilling to step into that world.

“If that were you or me today, we might have been looking to spend time getting to know the people and learn about life [there],” he says. “But she moved from one missionary household to another missionary household. She took a picture of a kid eating, but she was operating as a bystander, as an observer.”

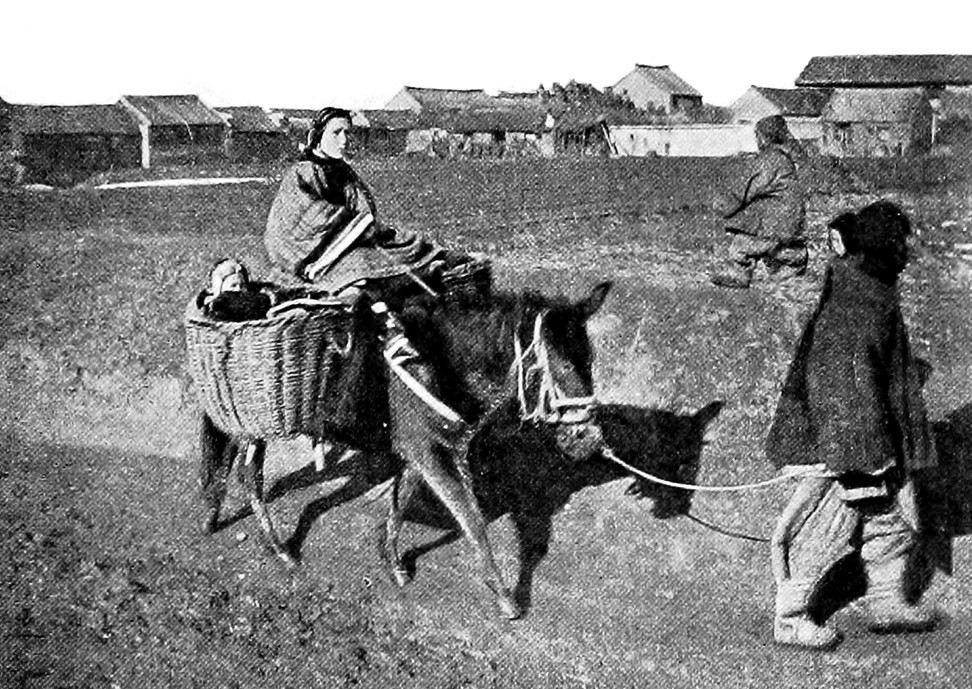

Bird was also interested in the rudimentary modes of transport used in the region. There’s a photograph of a Manchurian family on the move, with the baby in a basket and the mother atop a mule. She photographed wheelbarrows, which were used to transport goods and people, too.

Bird spent much of her time in the north of China and travelled into Manchuria. Photo: Isabella Bird/Chinese Pictures/Earnshaw Books

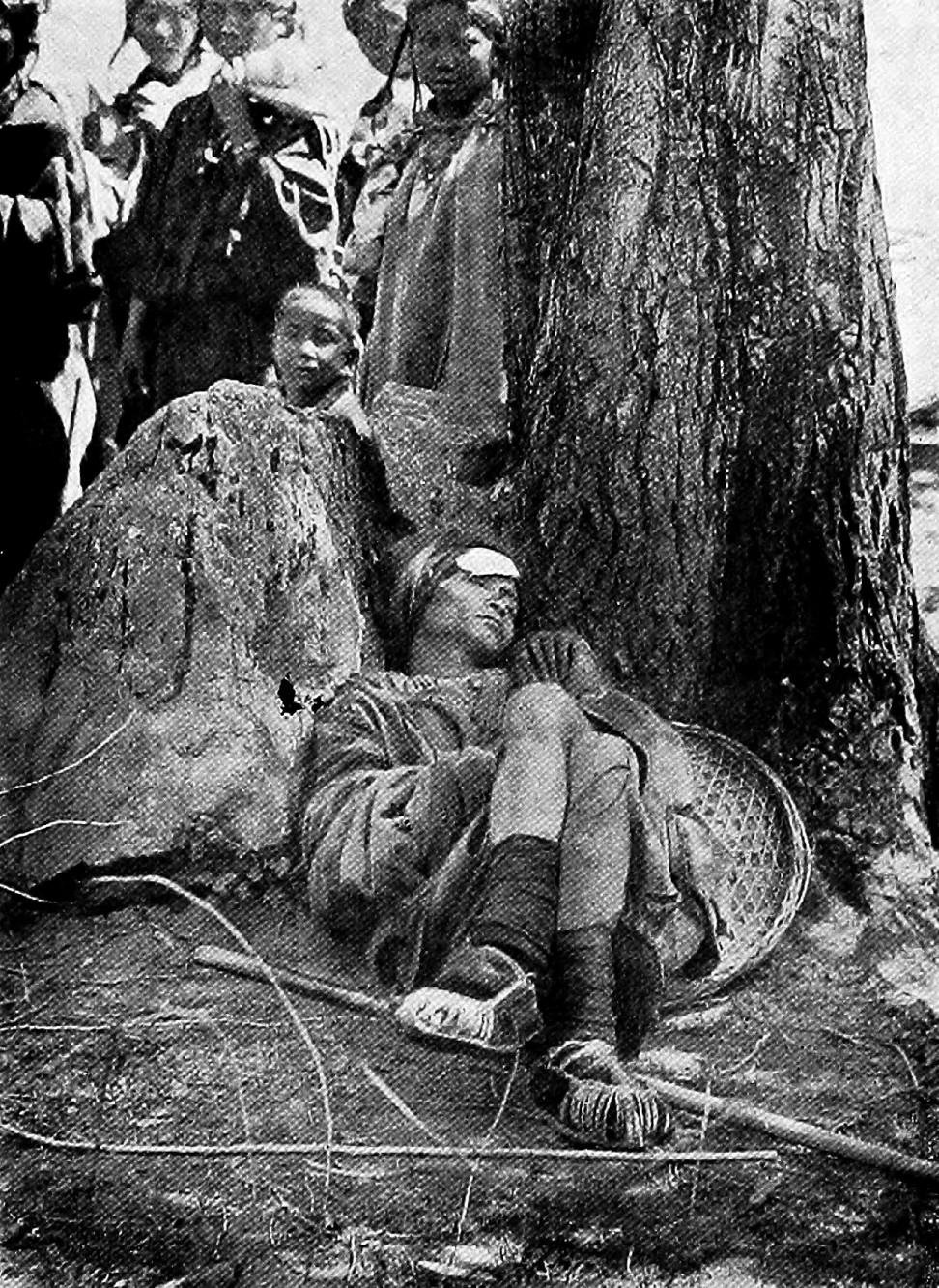

Perhaps one of her more disturbing images, titled the “Dying Coolie”, captured one of her bearers lying with his legs crossed under a tree. The story behind the image was that he had become ill, and his fellow bearers were ready to move on and leave him behind.

Although Bird was surprised by this seemingly callous pragmatism – he was dying, thus he was of no more use – she put a wet handkerchief on his brow to soothe him, took a photograph, and then herself also abandoned him.

“Is there a difference in the end? I don’t think so,” Earnshaw says. “But her Christian Victorian conscience was assuaged by bothering to put a handkerchief on his brow. Good for her.”

Perhaps one of Bird’s more disturbing images captured one of her bearers lying with his legs crossed under a tree. Photo: Isabella Bird/Chinese Pictures/Earnshaw Books

Bird also spent time in Beijing and took a photo of the Forbidden City from what would become Tiananmen Square. Her photo shows a more extensive set of royal buildings than exists today.

“You can see various gates and walls that no longer exist but give a sense of the wider Forbidden City – the home of the emperors at a time again before everything fell apart. It’s one of the most instructive photographs that I’ve seen of the Forbidden City,” Earnshaw says. “She recorded history.”

Chinese Pictures: China Through the Eyes of Isabella Bird, with a foreword by Graham Earnshaw, is published by Earnshaw Books.

No comments:

Post a Comment