PHOTO ESSAY / FIELD NOTES

How Fracking’s Appetite for Sand Is Devouring Rural Communities

Small towns in western Wisconsin are being divided by a little-known mining boom. An anthropologist who lives in the region set out to understand why.

THOMAS W. PEARSON / 4 MAY 2018

View Slideshow1 of 8 Photos

Thomas W. Pearson is a professor of cultural anthropology

Thomas W. Pearson is a professor of cultural anthropology

at the University of Wisconsin, Stout.

“Do you want to see the mine?” asks Harlan*.

“Of course,” I reply.

He fetches his boots. We head outside with his wife Edith and follow a row of fledgling soybeans as we stroll across a few acres of farmland.

It’s June 2014, and I’m in Dovre, a rural community in western Wisconsin where farm fields hug tree-covered hills and cattle graze lazily in the afternoon sun. A wooden 19th-century Lutheran church sits at the center of town, along with a one-room town hall.

Harlan and Edith spent most of their lives as dairy farmers in this once tight-knit community, just the two of them and around 40 cows. As we walk, they reminisce proudly about a life rooted in hard work and strong communal ties. Their view of community includes neighbors, but also something more, a commitment to reciprocity that entails a give-and-take between people, animals, and the land.

“We took care of the cows,” says Harlan, “and the cows took care of us.”

They speak fondly about the lifetime of labor they invested in their farm, putting up the barn, the silos, the shed, the milk house. They talk about maintaining the soil and managing the woods. Each hill, each of the surrounding farms, has its own story.

But now sand mines are erasing those stories—“putting the land blank,” as Harlan says.

Nearing retirement in the early 2000s, Harlan and Edith sold much of their property to another farmer and then built a house on a hill nearby, where they could look out at the land they passed on to its next steward. For people like Harlan and Edith, you don’t actually own land. You just care for it until you move on, a cycle they assumed would continue. Several years into their retirement, however, the other farmer sold the land to an out-of-state mining company and then left town.

We reach the end of the field and push through some brush, emerging at the edge of the mine—a 20-foot drop into a flat moonscape that covers about 120 acres, half of it curving around a hill and out of view. Harlan looks grief-stricken as he stares intently into the massive pit containing a unique treasure: pure silica sand. An excavator scoops loads of it into a dump truck.

The land erased. A community frayed.

Much of Harlan and Edith’s former farm in Dovre, Wisconsin, has been ripped open by sand mining. Another mine cuts into a distant hillside. Thomas W. Pearson

“Well, let’s put it this way,” explains Harlan. “Everybody that I know around here that sold to the companies moved out, so that should tell you something. And right now, we’re surrounded, and it just makes you feel like they’re squeezing you too.”

The mining company has visited Harlan and Edith several times, but they prefer to hold out. “They keep coming over,” says Edith, “and we’d both like to see it farmland. But how long can we hang on?”

Phrases such as “being squeezed” and “hanging on” allow Harlan and Edith to express a type of loss, even trauma, that is both individual and collective. They watch mining transform the landscape and feel alienated from a place that had once anchored their sense of belonging. They are not alone.

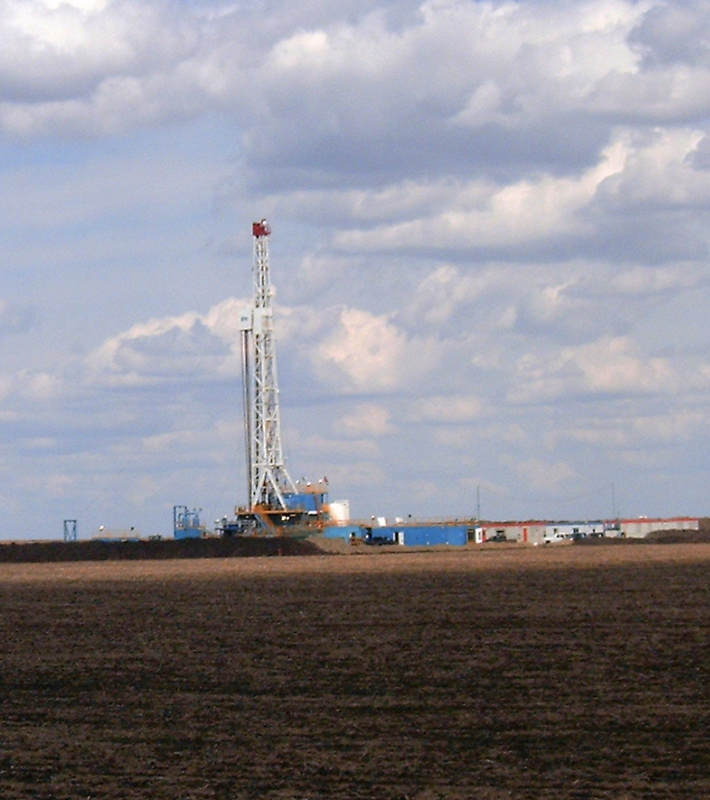

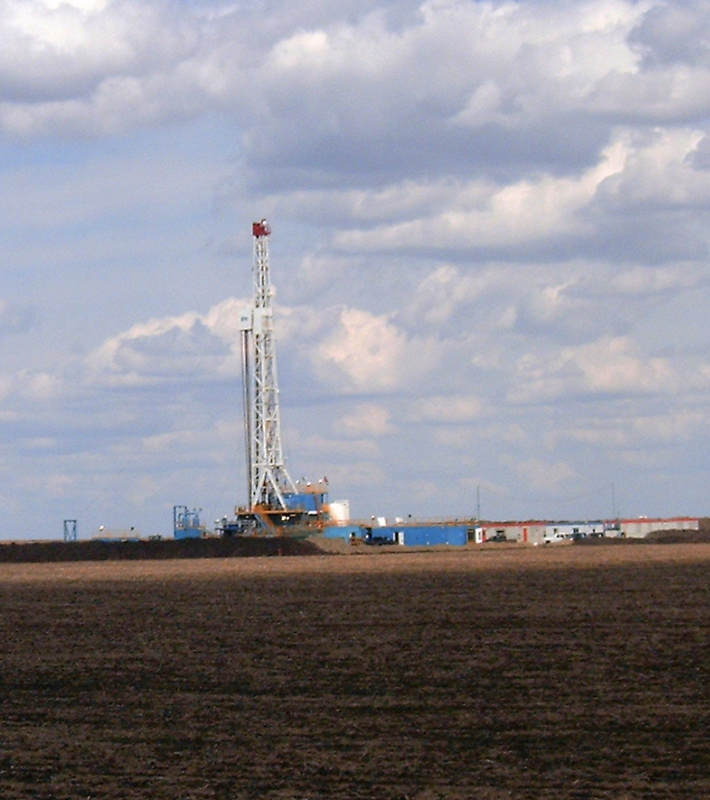

Over the past decade, the push to expand fossil fuel production in the United States through techniques such as hydraulic fracturing (commonly known as “fracking”) has reverberated far beyond oil rigs, pipeline routes, and petrochemical complexes, pulsating unexpectedly through communities like Dovre.

Fracking involves drilling deep into underground rock formations to release natural gas or oil. And it uses sand. Lots of it. Sand props open tiny fissures in the bedrock that are created during the fracking process, but not just any sand will do the trick. Highly pure silica sand is especially strong and resists being crushed thousands of feet below the surface. Round sand grains of consistent size allow hydrocarbons to flow more efficiently through the well.

During fracking, just one well can require several thousand tons of sand. To put that into perspective, industry forecasters predict that more than 100,000 new wells will be drilled over the next several years in Texas’ Permian Basin alone. But fracking is not limited to Texas. The last decade has also seen drilling booms in Pennsylvania, North Dakota, Wyoming, and Alberta, Canada, among other places. Last year nearly 70 million tons of sand was mined in the United States for fracking.

Landsat images from a USGS/NASA time-lapse video show landscape changes over the past 32 years in Barron County, Wisconsin. Several frac sand operations are clustered in Dovre (on the right), with two in neighboring Sioux Creek to the west (left). Landsat/Google Earth Engine

It just so happens that Wisconsin is uniquely positioned to supply fracking rigs in North America with some of the best sand available. Deposits of silica sand that formed some 500 million years ago are concentrated in western Wisconsin. While sand mining also occurs in Texas, Arizona, and Oklahoma, among other states, Wisconsin’s sand is especially prized for its strength and purity. It’s also close to the surface, so digging it up is relatively easy. And profitable.

Since the mid-2000s, the growth of fracking has powered a booming frac sand mining industry in western Wisconsin, with hundreds of operations cropping up across the countryside. Some people clearly benefit. Lucky landowners may see a windfall in selling or leasing to a mining company, and others may find work at mining operations or by driving trucks. Down the line, consumers enjoy cheap fuel. But at what cost?

Frac sand mining disturbs once-quiet rural towns with blasting, truck traffic, and industrial activity. It generates new environmental health risks, and some residents worry they are being exposed to microscopic particles of airborne silica dust that cause silicosis, an often fatal lung disease. Mining also flattens hills and alters scenic bluffs, disrupting not only a picturesque rural landscape but places that are deeply meaningful to people. Perhaps most significantly, the mining boom in communities like Dovre has fomented division and distrust as residents grapple with a resource boom that brings both wealth and ruin.

As the geographer Gavin Bridge writes, “One person’s discovery is another’s dispossession.”

Dispossessing people of resources or land is one thing, but the disruption caused by mining is commonly expressed as a form of assault—a kind of violence not only against the land but also people’s relationship to it. Residents often struggle to convey their emotions, drawing on images of invasion, illness, and violence, describing the hills as “cut open,” “disfigured,” or “scarred” by mining.

“No one invited the pillaging hordes of Genghis Khan either,” stated one resident in a letter to a local newspaper as she compared out-of-state mining companies to an occupying army. “Let’s prevent the cancer,” wrote another man, relating mining development to the metastatic spread of a life-threatening disease. “When they mine this, they rape this land,” a man told me, his gaze as empty as the pit being dug across the street from his home. “I don’t know any other word to use but ‘rape.’”

It’s not just retired farmers like Harlan and Edith who grapple with this kind of dispossession. Joe and Nancy moved to rural Wisconsin after living their entire lives in a large Midwestern city. The countryside represented a sanctuary from the grind of city life. Several years after they resettled, however, a neighbor sold a parcel of his land to a mining company. When the mining started, says Joe, it was like getting “smacked in the head with a two-by-four.” In addition to noise and dust, the pain was psychological, he remembers.

“The first year they were here,” Joe explains, “I’d go out and walk the dog in the morning … then I’d go sit in the basement. I felt like I was in solitary confinement, in jail. I mean, I gained weight anyhow [after retirement], but I gained a hell of a lot more weight then. I didn’t want to go outside. I was sick. Your life is just turned upside down.”

Lisa’s life has similarly been upended. Several years ago, two frac sand mines opened within a mile of her home and the barn where she boards several horses. Trucks drive by all day long. A processing plant runs nonstop, loading railcars by the thousands. She constantly deals with noise, vibration, and interrupted sleep, and she worries about possible exposure to silica dust.

“Do you want to see the mine?” asks Harlan*.

“Of course,” I reply.

He fetches his boots. We head outside with his wife Edith and follow a row of fledgling soybeans as we stroll across a few acres of farmland.

It’s June 2014, and I’m in Dovre, a rural community in western Wisconsin where farm fields hug tree-covered hills and cattle graze lazily in the afternoon sun. A wooden 19th-century Lutheran church sits at the center of town, along with a one-room town hall.

Harlan and Edith spent most of their lives as dairy farmers in this once tight-knit community, just the two of them and around 40 cows. As we walk, they reminisce proudly about a life rooted in hard work and strong communal ties. Their view of community includes neighbors, but also something more, a commitment to reciprocity that entails a give-and-take between people, animals, and the land.

“We took care of the cows,” says Harlan, “and the cows took care of us.”

They speak fondly about the lifetime of labor they invested in their farm, putting up the barn, the silos, the shed, the milk house. They talk about maintaining the soil and managing the woods. Each hill, each of the surrounding farms, has its own story.

But now sand mines are erasing those stories—“putting the land blank,” as Harlan says.

Nearing retirement in the early 2000s, Harlan and Edith sold much of their property to another farmer and then built a house on a hill nearby, where they could look out at the land they passed on to its next steward. For people like Harlan and Edith, you don’t actually own land. You just care for it until you move on, a cycle they assumed would continue. Several years into their retirement, however, the other farmer sold the land to an out-of-state mining company and then left town.

We reach the end of the field and push through some brush, emerging at the edge of the mine—a 20-foot drop into a flat moonscape that covers about 120 acres, half of it curving around a hill and out of view. Harlan looks grief-stricken as he stares intently into the massive pit containing a unique treasure: pure silica sand. An excavator scoops loads of it into a dump truck.

The land erased. A community frayed.

Much of Harlan and Edith’s former farm in Dovre, Wisconsin, has been ripped open by sand mining. Another mine cuts into a distant hillside. Thomas W. Pearson

“Well, let’s put it this way,” explains Harlan. “Everybody that I know around here that sold to the companies moved out, so that should tell you something. And right now, we’re surrounded, and it just makes you feel like they’re squeezing you too.”

The mining company has visited Harlan and Edith several times, but they prefer to hold out. “They keep coming over,” says Edith, “and we’d both like to see it farmland. But how long can we hang on?”

Phrases such as “being squeezed” and “hanging on” allow Harlan and Edith to express a type of loss, even trauma, that is both individual and collective. They watch mining transform the landscape and feel alienated from a place that had once anchored their sense of belonging. They are not alone.

Over the past decade, the push to expand fossil fuel production in the United States through techniques such as hydraulic fracturing (commonly known as “fracking”) has reverberated far beyond oil rigs, pipeline routes, and petrochemical complexes, pulsating unexpectedly through communities like Dovre.

Fracking involves drilling deep into underground rock formations to release natural gas or oil. And it uses sand. Lots of it. Sand props open tiny fissures in the bedrock that are created during the fracking process, but not just any sand will do the trick. Highly pure silica sand is especially strong and resists being crushed thousands of feet below the surface. Round sand grains of consistent size allow hydrocarbons to flow more efficiently through the well.

During fracking, just one well can require several thousand tons of sand. To put that into perspective, industry forecasters predict that more than 100,000 new wells will be drilled over the next several years in Texas’ Permian Basin alone. But fracking is not limited to Texas. The last decade has also seen drilling booms in Pennsylvania, North Dakota, Wyoming, and Alberta, Canada, among other places. Last year nearly 70 million tons of sand was mined in the United States for fracking.

Landsat images from a USGS/NASA time-lapse video show landscape changes over the past 32 years in Barron County, Wisconsin. Several frac sand operations are clustered in Dovre (on the right), with two in neighboring Sioux Creek to the west (left). Landsat/Google Earth Engine

It just so happens that Wisconsin is uniquely positioned to supply fracking rigs in North America with some of the best sand available. Deposits of silica sand that formed some 500 million years ago are concentrated in western Wisconsin. While sand mining also occurs in Texas, Arizona, and Oklahoma, among other states, Wisconsin’s sand is especially prized for its strength and purity. It’s also close to the surface, so digging it up is relatively easy. And profitable.

Since the mid-2000s, the growth of fracking has powered a booming frac sand mining industry in western Wisconsin, with hundreds of operations cropping up across the countryside. Some people clearly benefit. Lucky landowners may see a windfall in selling or leasing to a mining company, and others may find work at mining operations or by driving trucks. Down the line, consumers enjoy cheap fuel. But at what cost?

Frac sand mining disturbs once-quiet rural towns with blasting, truck traffic, and industrial activity. It generates new environmental health risks, and some residents worry they are being exposed to microscopic particles of airborne silica dust that cause silicosis, an often fatal lung disease. Mining also flattens hills and alters scenic bluffs, disrupting not only a picturesque rural landscape but places that are deeply meaningful to people. Perhaps most significantly, the mining boom in communities like Dovre has fomented division and distrust as residents grapple with a resource boom that brings both wealth and ruin.

As the geographer Gavin Bridge writes, “One person’s discovery is another’s dispossession.”

Dispossessing people of resources or land is one thing, but the disruption caused by mining is commonly expressed as a form of assault—a kind of violence not only against the land but also people’s relationship to it. Residents often struggle to convey their emotions, drawing on images of invasion, illness, and violence, describing the hills as “cut open,” “disfigured,” or “scarred” by mining.

“No one invited the pillaging hordes of Genghis Khan either,” stated one resident in a letter to a local newspaper as she compared out-of-state mining companies to an occupying army. “Let’s prevent the cancer,” wrote another man, relating mining development to the metastatic spread of a life-threatening disease. “When they mine this, they rape this land,” a man told me, his gaze as empty as the pit being dug across the street from his home. “I don’t know any other word to use but ‘rape.’”

It’s not just retired farmers like Harlan and Edith who grapple with this kind of dispossession. Joe and Nancy moved to rural Wisconsin after living their entire lives in a large Midwestern city. The countryside represented a sanctuary from the grind of city life. Several years after they resettled, however, a neighbor sold a parcel of his land to a mining company. When the mining started, says Joe, it was like getting “smacked in the head with a two-by-four.” In addition to noise and dust, the pain was psychological, he remembers.

“The first year they were here,” Joe explains, “I’d go out and walk the dog in the morning … then I’d go sit in the basement. I felt like I was in solitary confinement, in jail. I mean, I gained weight anyhow [after retirement], but I gained a hell of a lot more weight then. I didn’t want to go outside. I was sick. Your life is just turned upside down.”

Lisa’s life has similarly been upended. Several years ago, two frac sand mines opened within a mile of her home and the barn where she boards several horses. Trucks drive by all day long. A processing plant runs nonstop, loading railcars by the thousands. She constantly deals with noise, vibration, and interrupted sleep, and she worries about possible exposure to silica dust.

Frac sand mining generates silica dust, which is hazardous when inhaled. One of the mines in Dovre has installed air monitors in an effort to measure the impacts of mining on air quality. Thomas W. Pearson

“I’m told I’m exaggerating when I talk about the sheer dust that’s in this house. In the middle of summer, I can start [dusting] on this end,” she says, pointing to one side of her kitchen, “and by the time I get to this end, there’s a layer of dust on that countertop.”

She has complained to local officials, but as she sees it, they support the mining industry and have downplayed her concerns. “I’m told that I’m lying, that I’m ridiculous, I’m exaggerating, I’m crazy.”

Uncertainty about the nature of the dust is a source of continual anxiety. She feels unsafe in her own home and abandoned by elected officials who she thought were supposed to watch out for her well-being.

To truly grasp her experience, it is important to recognize that people in the United States associate certain meanings with the idea of home: order, security, investment in the future. Mining may disrupt these expectations, leaving people feeling extremely vulnerable, if not hopeless.

It makes sense that some residents would prefer to live elsewhere. But leaving one’s home also brings with it complex feelings of loss.

Heidi says she felt “empty” when she sold her 19th-century farmhouse after multiple mining operations were permitted to operate nearby. The mining company bought her out so that they wouldn’t have to deal with a frustrated, outspoken resident living next door. She accepted the buyout, her one chance to “escape,” as she puts it. Others were “not so lucky,” she says, and she struggles with the guilt of leaving friends and neighbors behind.

While she elected to sell her home to a mining company, it was a choice constrained by circumstance. Her only other option, she says, would have been “to grow old and be some pissy old woman sitting in the middle of the driveway yelling at all the trucks going by. I would’ve lost everything.”

“It was very traumatizing,” explains Heidi, “to feel pushed out of our home.”

The sense of loss expressed by some people in Dovre extends beyond feelings of vulnerability or the trauma of relocation. Like Harlan and Edith, some lose connections to places that were once immensely meaningful—that were part of them.

Marleen has lived in Dovre for over 80 years. Historical photos of her farm, which her grandfather purchased in the 1890s, hang prominently in her living room. When hosting visitors, she likes to thumb through photo albums and tell stories about family and friends. Her husband was laid to rest in the cemetery next to the Lutheran church.

For Marleen, memories are etched into the rural landscape, a genealogy of kin ties linking past to present. These ties transcend her own property. Her grandfather, for instance, worked on a different farm up the road when he first arrived from Norway—one that is now being mined for sand. In fact, it is the same land that Harlan and Edith once owned.

“And I [had] always felt good about that,” Marleen says mournfully, “that I could go up there, and I was actually stepping on soil where my grandfather lived.”

Now the hills are gone, replaced by “pyramids of sand,” she scoffs. These are the stockpiles at a nearby processing plant being readied for shipment to the drilling rigs.

The land has been put blank.

“It’s sickening, just sickening,” says Marleen. “I wish it was like a dream, and you wake up and it was a dream and it didn’t happen.”

*Pseudonyms have been used to protect the identities of people interviewed in Dovre over the course of the author’s research.

**Editors’ note: People and places described in this essay are further discussed in the author’s book, When the Hills Are Gone: Frac Sand Mining and the Struggle for Community, and his article in the journal Human Organization.

In west-central Wisconsin, frac sand mines struggle amid industry changes

Eric Lindquist Eau Claire Leader-Telegram

Jun 25, 2019

In this Thursday, Dec. 15, 2011 photo, frac sand destined for the oil and

gas fields piles up at the EOG Resources Inc. processing plant in Chippewa Falls.

STEVE KARNOWSKI, Associated Press

A relatively new industry to west-central Wisconsin continues to give area residents a modern-day lesson in old-fashioned economics.

The regional frac sand industry, which burst onto the scene about a decade ago, already has gone through at least two boom-and-bust cycles and is in the midst of a bust that has idled several mines.

The source of the strife comes down to the basic economic principle of supply and demand.

While demand for frac sand remains strong, the supply has expanded dramatically in the last two years as energy companies have built a number of mines closer to oilfields in Texas and Oklahoma, said UW-Eau Claire geology professor Kent Syverson, who also serves as a consultant for the frac sand industry. The production expansion has pushed down prices and enabled oil drillers to get local sand for less than the cost of shipping it from Wisconsin.

“I think the boom years are over,” Syverson said, referring to the period from 2011 to 2014 when sand mines, processing plants and rail loading facilities were popping up like dandelions across west-central Wisconsin to take advantage of the region’s silica sand reserves.

“The capital has already been invested in Wisconsin,” he said, “so the real questions are how much of this sand will still be needed and how many of these higher-cost operations that are taken off line will never come back.”

Ryan Carbrey, senior vice president of shale research for Rystad Energy in Houston, said Upper Midwest mines with annual capacity of 18 million tons of frac sand already have been idled this year, and his company projects that total will rise to 30 million tons by the end of 2019.

The vast majority of the mines producing what is known in the industry as northern white sand are in Wisconsin, with the bulk of them located within 80 miles of Eau Claire.

The sand is used in hydraulic fracturing — the drilling technique commonly known as fracking that involves injecting a mixture of sand, water and chemicals deep into underground wells to force oil and natural gas to the surface. The sand is used to hold open fissures in the rock.

Northern white sand, prized by fracking companies for its coarseness, durability and the spherical shape of its grains, is still considered to be of higher quality than the sand produced in Texas, but producers have developed methods to make the lower-quality sand work well enough to satisfy their needs, Carbrey said.

Most importantly to producers, the Texas sand is cheaper because it doesn’t have to be shipped more than 1,000 miles by rail from Wisconsin to the oil and gas deposits in the Permian Basin in west Texas and southeast New Mexico.

“Wisconsin sand is still the Cadillac of all sands, but these companies in the Permian Basin are saying they can make more money driving a Chevy than a Cadillac,” Syverson said. “It’s all a cost-benefit analysis.”

As a result, demand has dramatically increased for the finer grain sand, which is much more plentiful than northern white sand, he said.

“The demand structure has flipped, and it appears right now that the industry has moved toward the finer sand and it’s hard to imagine that going back,” Syverson said. “It was just kind of mind-blowing to have this seismic shift from coarser to finer grain sand in just a couple years.”

All of this is important, Carbrey said, because the Permian Basin accounts for about half of the nation’s shale energy production. He added that the relatively new west Texas mines already have the capacity to produce more than 70 million tons of frac sand per year.

Region hit hard

The impact of the demand shift is evident across west-central Wisconsin, with once-booming sand mining and processing facilities sitting dormant.

Superior Silica Sands has idled three of its five frac sand mines in Chippewa and Barron counties, said Sharon Macek, the company’s manager of mine planning and industrial relations in Wisconsin. Superior Silica is still producing sand at a mine near Chetek and one in the Barron County town of Arland, and its dry plant near Barron is fully operational.

Emerge Energy Services, which owns Superior Silica, entered into a debt restructuring deal with its lenders in April, so company officials can’t comment further on operations at this time, Macek said.

Covia, created by a merger of Fairmount Santrol and Unimin, announced in a filing with the Securities and Exchange Commission that it was idling operations in Maiden Rock as well as several mines across the country.

A company spokesman also confirmed Covia has reduced production at its mine in Menomonie.

Hi-Crush idled its Whitehall frac sand production facility in September but then announced early this year it was resuming operations at the Whitehall mine and halting production at its facility in Augusta. The Houston-based company said its Augusta workforce would be moving to the Whitehall plant, which is about 30 miles away.

The decisions were based on increased demand from oil and gas industry customers, predominantly in the Northeast, that are more efficiently served by Hi-Crush’s Blair and Whitehall facilities located on the Canadian National Railway, CEO Robert Rasmus said in a news release. Hi-Crush was the first sand company to establish a mine in the Permian Basin.A company spokesman said Hi-Crush mines in Blair, Whitehall and Wyeville are fully operational and that the firm’s Wisconsin employment is down about 9 percent this year, with about about half of the decline resulting from attrition.

The Augusta facility remains dormant, Mayor Delton Thorson said Thursday.

“They’ve got a lot of investment here, so it’s hard to imagine this shutdown will be permanent, but if they have sand sources closer to the oil fields, you can understand why they would go there to get it,” Thorson said. “My guess is that sooner or later the wheel will spin back to here.”

Outlook unclear

Samir Nangia, director of energy consulting at analytics firm IHS Markit, told Wisconsin Public Radio last month that as much as 75 percent of Wisconsin sand mines might need to be closed temporarily or even permanently. Nangia couldn’t be reached last week for further comment.

Carbrey offered a glimmer of hope for Wisconsin frac sand producers by pointing out that other major shale energy deposits in North Dakota and Pennsylvania continue to rely on northern white sand.

“In those regions, there’s not really much good local sand,” he said.

Despite the major shift to using sand found closer to oil fields, the long-term outlook is unclear because the finer sand leads to wells in which production declines faster than those using northern white sand.

“It is cheaper, but it doesn’t produce as high quality of a well,” Carbrey said. “No one really know yet if in-basin sands provide positive economic value. We really don’t know how it will all shake out.”

A relatively new industry to west-central Wisconsin continues to give area residents a modern-day lesson in old-fashioned economics.

The regional frac sand industry, which burst onto the scene about a decade ago, already has gone through at least two boom-and-bust cycles and is in the midst of a bust that has idled several mines.

The source of the strife comes down to the basic economic principle of supply and demand.

While demand for frac sand remains strong, the supply has expanded dramatically in the last two years as energy companies have built a number of mines closer to oilfields in Texas and Oklahoma, said UW-Eau Claire geology professor Kent Syverson, who also serves as a consultant for the frac sand industry. The production expansion has pushed down prices and enabled oil drillers to get local sand for less than the cost of shipping it from Wisconsin.

“I think the boom years are over,” Syverson said, referring to the period from 2011 to 2014 when sand mines, processing plants and rail loading facilities were popping up like dandelions across west-central Wisconsin to take advantage of the region’s silica sand reserves.

“The capital has already been invested in Wisconsin,” he said, “so the real questions are how much of this sand will still be needed and how many of these higher-cost operations that are taken off line will never come back.”

Ryan Carbrey, senior vice president of shale research for Rystad Energy in Houston, said Upper Midwest mines with annual capacity of 18 million tons of frac sand already have been idled this year, and his company projects that total will rise to 30 million tons by the end of 2019.

The vast majority of the mines producing what is known in the industry as northern white sand are in Wisconsin, with the bulk of them located within 80 miles of Eau Claire.

The sand is used in hydraulic fracturing — the drilling technique commonly known as fracking that involves injecting a mixture of sand, water and chemicals deep into underground wells to force oil and natural gas to the surface. The sand is used to hold open fissures in the rock.

Northern white sand, prized by fracking companies for its coarseness, durability and the spherical shape of its grains, is still considered to be of higher quality than the sand produced in Texas, but producers have developed methods to make the lower-quality sand work well enough to satisfy their needs, Carbrey said.

Most importantly to producers, the Texas sand is cheaper because it doesn’t have to be shipped more than 1,000 miles by rail from Wisconsin to the oil and gas deposits in the Permian Basin in west Texas and southeast New Mexico.

“Wisconsin sand is still the Cadillac of all sands, but these companies in the Permian Basin are saying they can make more money driving a Chevy than a Cadillac,” Syverson said. “It’s all a cost-benefit analysis.”

As a result, demand has dramatically increased for the finer grain sand, which is much more plentiful than northern white sand, he said.

“The demand structure has flipped, and it appears right now that the industry has moved toward the finer sand and it’s hard to imagine that going back,” Syverson said. “It was just kind of mind-blowing to have this seismic shift from coarser to finer grain sand in just a couple years.”

All of this is important, Carbrey said, because the Permian Basin accounts for about half of the nation’s shale energy production. He added that the relatively new west Texas mines already have the capacity to produce more than 70 million tons of frac sand per year.

Region hit hard

The impact of the demand shift is evident across west-central Wisconsin, with once-booming sand mining and processing facilities sitting dormant.

Superior Silica Sands has idled three of its five frac sand mines in Chippewa and Barron counties, said Sharon Macek, the company’s manager of mine planning and industrial relations in Wisconsin. Superior Silica is still producing sand at a mine near Chetek and one in the Barron County town of Arland, and its dry plant near Barron is fully operational.

Emerge Energy Services, which owns Superior Silica, entered into a debt restructuring deal with its lenders in April, so company officials can’t comment further on operations at this time, Macek said.

Covia, created by a merger of Fairmount Santrol and Unimin, announced in a filing with the Securities and Exchange Commission that it was idling operations in Maiden Rock as well as several mines across the country.

A company spokesman also confirmed Covia has reduced production at its mine in Menomonie.

Hi-Crush idled its Whitehall frac sand production facility in September but then announced early this year it was resuming operations at the Whitehall mine and halting production at its facility in Augusta. The Houston-based company said its Augusta workforce would be moving to the Whitehall plant, which is about 30 miles away.

The decisions were based on increased demand from oil and gas industry customers, predominantly in the Northeast, that are more efficiently served by Hi-Crush’s Blair and Whitehall facilities located on the Canadian National Railway, CEO Robert Rasmus said in a news release. Hi-Crush was the first sand company to establish a mine in the Permian Basin.A company spokesman said Hi-Crush mines in Blair, Whitehall and Wyeville are fully operational and that the firm’s Wisconsin employment is down about 9 percent this year, with about about half of the decline resulting from attrition.

The Augusta facility remains dormant, Mayor Delton Thorson said Thursday.

“They’ve got a lot of investment here, so it’s hard to imagine this shutdown will be permanent, but if they have sand sources closer to the oil fields, you can understand why they would go there to get it,” Thorson said. “My guess is that sooner or later the wheel will spin back to here.”

Outlook unclear

Samir Nangia, director of energy consulting at analytics firm IHS Markit, told Wisconsin Public Radio last month that as much as 75 percent of Wisconsin sand mines might need to be closed temporarily or even permanently. Nangia couldn’t be reached last week for further comment.

Carbrey offered a glimmer of hope for Wisconsin frac sand producers by pointing out that other major shale energy deposits in North Dakota and Pennsylvania continue to rely on northern white sand.

“In those regions, there’s not really much good local sand,” he said.

Despite the major shift to using sand found closer to oil fields, the long-term outlook is unclear because the finer sand leads to wells in which production declines faster than those using northern white sand.

“It is cheaper, but it doesn’t produce as high quality of a well,” Carbrey said. “No one really know yet if in-basin sands provide positive economic value. We really don’t know how it will all shake out.”

Frac Sand Mining

SIERRA CLUB WISCONSIN

Hydraulic fracturing, or “fracking,” is the controversial practice of extracting fossil fuels from hard-to-reach shale deposits. In this process, fossil fuel corporations force these underground shale rock formations to crack and split open by blasting them with a mixture of highly pressurized water, high quality sands, and toxic substances, unleashing massive quantities of natural gas and oil. The sand helps to prop these fissures open so the fossil fuels can be released and captured. As a result, waste material often seeps into groundwater, or is collected and then injected back into the ground using waste disposal wells. While not a new development, the amount of fracking has dramatically accelerated in recent years.

This process pollutes our air and water and can even lead to induced earthquakes and flammable tap water (check out this video of a woman taking a match to her kitchen faucet). It also unleashes methane, a greenhouse gas that is 30 times as potent as carbon dioxide, into the atmosphere — contributing to climate change and reinforcing our dependence on fossil fuels, delaying the urgently necessary transition to renewable energy sources. Luckily, Wisconsin doesn’t have any known natural gas deposits, so we have been spared from the immediate harms of fracking. But our state does have an indirect — yet important — connection to this destructive industry…

This process pollutes our air and water and can even lead to induced earthquakes and flammable tap water (check out this video of a woman taking a match to her kitchen faucet). It also unleashes methane, a greenhouse gas that is 30 times as potent as carbon dioxide, into the atmosphere — contributing to climate change and reinforcing our dependence on fossil fuels, delaying the urgently necessary transition to renewable energy sources. Luckily, Wisconsin doesn’t have any known natural gas deposits, so we have been spared from the immediate harms of fracking. But our state does have an indirect — yet important — connection to this destructive industry…

What is frac sand mining?

Western Wisconsin has beautiful rolling hills and scenic bluffs that stretch from the banks of the Mississippi River into the central part of our state. Beyond their aesthetic appeal and intrinsic value, they facilitate hiking and other recreational activities as well as provide habitats for many species of native flora and fauna. But for the fracking industry, these bluffs are important for just one thing — high quality sand.

Fracking requires a steady supply of special silica sand with grains of ideal size, shape, strength, and purity — called frac sand. And fracking necessitates enormous quantities of it; in fact, each natural gas or oil well uses millions of pounds of this sand in its lifetime. Because so much sand is needed, frac sand mining — the process of extracting the sand from the earth — has developed to satisfy the surging demand.

In a lot of places, this sand is rare. Unfortunately for us, the majestic bluffs that have enhanced the beauty of our state’s western landscape for millennia contain the ideal type of sand needed for fracking. And the fossil fuel industry and mining corporations have figured it out.

Western Wisconsin has beautiful rolling hills and scenic bluffs that stretch from the banks of the Mississippi River into the central part of our state. Beyond their aesthetic appeal and intrinsic value, they facilitate hiking and other recreational activities as well as provide habitats for many species of native flora and fauna. But for the fracking industry, these bluffs are important for just one thing — high quality sand.

Fracking requires a steady supply of special silica sand with grains of ideal size, shape, strength, and purity — called frac sand. And fracking necessitates enormous quantities of it; in fact, each natural gas or oil well uses millions of pounds of this sand in its lifetime. Because so much sand is needed, frac sand mining — the process of extracting the sand from the earth — has developed to satisfy the surging demand.

In a lot of places, this sand is rare. Unfortunately for us, the majestic bluffs that have enhanced the beauty of our state’s western landscape for millennia contain the ideal type of sand needed for fracking. And the fossil fuel industry and mining corporations have figured it out.

The Sand Rush

The boom in natural gas and fracking has triggered a subsequent “sand rush” in western Wisconsin, causing mining corporations to scramble to supply natural gas wells with a necessary ingredient. Wisconsin now has 128 industrial sand facilities, including mines, processing plants, and rail load-outs.

To extract this sand, mining companies use open pit and hilltop removal mining, which destroys landscapes, poisons our environment, and harms quality of life. Enormous tracts of land are cleared of all greenery, and then the “overburden” — which is what miners call all of the soil and life that exists above whatever mineral they are extracting — is excavated using heavy machinery and explosives. And as the name suggests, hilltop removal mining involves literally destroying entire hills and bluffs.

Because the sand is actually in rock form, it must be pulverized and then washed, to remove any impurities. The waste materials are then collected in vast pools of sludge, while the purified frac sand is stored in large piles awaiting transportation to natural gas and oil wells.

Why is frac sand mining bad for Wisconsin?

1) It’s environmentally destructive. Frac sand mining requires clearing land of forests, grasslands, meadows, and wetlands, eliminating valuable ecosystems and habitats. But it also generates alarming levels of air and water pollution. The mining process, especially the excavation and pulverization steps, release silica dust — a known carcinogen that causes lung cancer — into the air. Long term low level exposure can also cause silicosis, which is debilitating, incurable, and often fatal, as well as other respiratory diseases, meaning miners and people living near the mines are at risk. In one study, 79 percent of air samples at frac sand sites revealed levels of silica dust over the exposure limit, and a third were so high that most respirators wouldn’t be capable of removing it

To extract this sand, mining companies use open pit and hilltop removal mining, which destroys landscapes, poisons our environment, and harms quality of life. Enormous tracts of land are cleared of all greenery, and then the “overburden” — which is what miners call all of the soil and life that exists above whatever mineral they are extracting — is excavated using heavy machinery and explosives. And as the name suggests, hilltop removal mining involves literally destroying entire hills and bluffs.

Because the sand is actually in rock form, it must be pulverized and then washed, to remove any impurities. The waste materials are then collected in vast pools of sludge, while the purified frac sand is stored in large piles awaiting transportation to natural gas and oil wells.

Why is frac sand mining bad for Wisconsin?

1) It’s environmentally destructive. Frac sand mining requires clearing land of forests, grasslands, meadows, and wetlands, eliminating valuable ecosystems and habitats. But it also generates alarming levels of air and water pollution. The mining process, especially the excavation and pulverization steps, release silica dust — a known carcinogen that causes lung cancer — into the air. Long term low level exposure can also cause silicosis, which is debilitating, incurable, and often fatal, as well as other respiratory diseases, meaning miners and people living near the mines are at risk. In one study, 79 percent of air samples at frac sand sites revealed levels of silica dust over the exposure limit, and a third were so high that most respirators wouldn’t be capable of removing it

from the air. But it’s not just the air — water is affected too. These mines contaminate local waterways with toxic substances like heavy metals and polyacrylamide, and there have been several cases of waste liquid spills, including one that released 10 million gallons of waste into tributaries of the Trempealeau River — leading to dangerous levels of heavy metals in the water. Additionally, frac sand mining requires immense quantities of water, contributing to water overuse and waste. In fact, just one mine can demand up to 2 million gallons of water a day. Finally, these mines increase noise and light pollution; some residents in Trempealeau County said they can’t even open their windows due to “constant noise and light.”

2) It enables fracking. As previously discussed, fracking for natural gas and oil is incredibly detrimental to the environment and generates a litany of social ills — from poisoning our air and water with harmful pollutants and carcinogens to exacerbating climate change to even inducing earthquakes. Basically, there is no safe amount of fracking, and the practice needs to come to an immediate halt if we want to protect both local communities and the planet as a whole. Because frac sand mining provides the necessary ingredients that fuel this destructive process, these frac sands mines act as accomplices to the fossil fuel industry and help perpetuate this unjust and degrading system.

3) It leads to volatile boom-and-bust cycles that spell disaster for local economies. At first, frac sand mines might appear to be beneficial to the economy, as they hire workers and generate economic activity. But this activity is unsustainable and often disconnected with the rest of the local economy, meaning much of the money generated through the mining process does little to benefit Wisconsin’s communities and makes the economy less diversified and more vulnerable to the wild fluctuations of the sand market. And the uncertain and unstable jobs that are actually provided make up just a small fraction of the total employment in the region and can actually displace more sustainable and socially beneficial jobs. Plus, technological improvements mean less and

2) It enables fracking. As previously discussed, fracking for natural gas and oil is incredibly detrimental to the environment and generates a litany of social ills — from poisoning our air and water with harmful pollutants and carcinogens to exacerbating climate change to even inducing earthquakes. Basically, there is no safe amount of fracking, and the practice needs to come to an immediate halt if we want to protect both local communities and the planet as a whole. Because frac sand mining provides the necessary ingredients that fuel this destructive process, these frac sands mines act as accomplices to the fossil fuel industry and help perpetuate this unjust and degrading system.

3) It leads to volatile boom-and-bust cycles that spell disaster for local economies. At first, frac sand mines might appear to be beneficial to the economy, as they hire workers and generate economic activity. But this activity is unsustainable and often disconnected with the rest of the local economy, meaning much of the money generated through the mining process does little to benefit Wisconsin’s communities and makes the economy less diversified and more vulnerable to the wild fluctuations of the sand market. And the uncertain and unstable jobs that are actually provided make up just a small fraction of the total employment in the region and can actually displace more sustainable and socially beneficial jobs. Plus, technological improvements mean less and

less workers are hired as the years go on, and more profits are hoarded by the executives and corporations that own the mines. And the boom years are often short-lived; already, Wisconsin frac sand mines are going idle or bankrupt and laying off workers as the market becomes oversaturated with too much sand. More profitable mines selling cheaper sand closer to oil and gas wells are also opening up in Texas and New Mexico, outcompeting these Wisconsin mines and causing their market share to plummet. Regardless of the competition, frac sands mining, because it relies on depleting the earth’s finite resources, is inevitably unsustainable and inescapably a short-term endeavor. And this isn’t the first downturn for the nascent industry — 2016 also saw mine closures and layoffs. What this means is that frac sand jobs are notoriously insecure and precarious: once the mine folds, the jobs disappear and all that remains is the environmental devastation, the harmful health consequences, the higher carbon emissions, and the deep scars on Wisconsin’s landscape.

What can we do to stop frac sand mining?

Local activists are turning people out to public hearings, questioning the mining companies and educating people in the area about the dangers that exist, and they’ve had some success in preventing some of the harms that these mines inflict on the state. Unfortunately, however, once one mine is stopped, the companies just pop up with a new mine in the next town over, evading laws and exploiting new localities inexperienced at dealing with these manipulative mining corporations.

The one action that has had some success in blocking new frac sand mines are moratoriums. Towns, cities, and counties have established short-term moratoriums in order to better study the impacts of mining proposals. As expected, though, sand mine companies have actively fought against these moratoriums. For example, High Country Sand sued Eau Claire County after the county established a moratorium on the company’s proposed mine. Worse, in the last days of the legislative session, the legislature passed 2011 Wisconsin Act 144. The law makes it far more difficult for cities, towns, and villages to establish development moratorium ordinances, effectively blocking local communities from creating moratoriums.

Therefore, we need to enact a statewide moratorium on new frac sand mines in Wisconsin, at least until the state conducts a comprehensive study of the impacts, and we need stronger regulations to protect public health, local communities, and sensitive habitats from the degradation that results from the rapid proliferation of these inherently unsustainable mines.

The mining companies claim they are bringing jobs into the area, and we do need jobs. But these are insecure and short-term jobs that only employ a small fraction of the population. There are better ways to create real, sustainable jobs.

If you’d like to help us in our fight against these frac sand mining companies and protect Wisconsin, please volunteer with us!

The Permian Rush Is Creating A Frac Sand Shortage

SEE https://plawiuk.blogspot.com/search?q=FRAC

SEE https://plawiuk.blogspot.com/search?q=FRACKING

SEE https://plawiuk.blogspot.com/search?q=SAND

SEE https://plawiuk.blogspot.com/search?q=FRAC+SAND

What can we do to stop frac sand mining?

Local activists are turning people out to public hearings, questioning the mining companies and educating people in the area about the dangers that exist, and they’ve had some success in preventing some of the harms that these mines inflict on the state. Unfortunately, however, once one mine is stopped, the companies just pop up with a new mine in the next town over, evading laws and exploiting new localities inexperienced at dealing with these manipulative mining corporations.

The one action that has had some success in blocking new frac sand mines are moratoriums. Towns, cities, and counties have established short-term moratoriums in order to better study the impacts of mining proposals. As expected, though, sand mine companies have actively fought against these moratoriums. For example, High Country Sand sued Eau Claire County after the county established a moratorium on the company’s proposed mine. Worse, in the last days of the legislative session, the legislature passed 2011 Wisconsin Act 144. The law makes it far more difficult for cities, towns, and villages to establish development moratorium ordinances, effectively blocking local communities from creating moratoriums.

Therefore, we need to enact a statewide moratorium on new frac sand mines in Wisconsin, at least until the state conducts a comprehensive study of the impacts, and we need stronger regulations to protect public health, local communities, and sensitive habitats from the degradation that results from the rapid proliferation of these inherently unsustainable mines.

The mining companies claim they are bringing jobs into the area, and we do need jobs. But these are insecure and short-term jobs that only employ a small fraction of the population. There are better ways to create real, sustainable jobs.

If you’d like to help us in our fight against these frac sand mining companies and protect Wisconsin, please volunteer with us!

The Permian Rush Is Creating A Frac Sand Shortage

By Julianne Geiger - Jul 18, 2018 OILPRICE

The ‘mega-frac’ is turning the typically annoying sand of West Texas into the new gold, and the oil and gas land rush on the Permian Basin has now extended into the dry, gritty sand that only a year ago few would have given a second thought.

While most are busy watching all land grabs by oil and gas producers in the Permian, much less attention has been paid to the secondary land rush for the sandy wasteland that could ease some of the bottlenecks for producers who need frac sand to make anything happen.

Now as some herald a new phase of deal-making and consolidation following the Permian oil and gas land rush, the same may end up happening for all those frac sand producers who have followed them there.

As many as 23 new frac sand mines are being developed in West Texas this year, according to reports cited by Bloomberg.

Why Texas, And How Much Frac Sand Do We Really Need?

The process of hydraulic fracturing involves injecting highly pressurized water into a well and then pouring sand into it in order to keep the tiny fractures created by the water blast open. After that, the holes are widened to allow the crude to ooze out of the shale rock. The more fractures created in a rock, the more oil and gas producers will get out of it. That notion of well completion intensity is driving increasing sand usage per well.

It’s all put the frack sand subsector very much on investor radar as a backdoor into the lucrative shale business. So much so, in fact, that some have even started referring to the frac sand situation as “proppant-geddon”.

So the answer to ‘why Texas’ is a simple one: Frac sand producers follow the oil producers, and they’re descending on the Permian. And until the run on Texas sand, producers were largely dependent on expensive ‘white sand’ mined in Wisconsin and Minnesota. The brown sand of Texas is cheaper. And when it’s right in your backyard, producers save a bundle.

It’s cheaper because it’s easier to mine. Wisconsin’s sand is locked up in sandstone, while Texas’ is just hanging out in big dunes. That’s where the lower price comes into play.Related: The Best And Worst Oil Price Predictions

Of course, it’s bad news for Wisconsin, which won’t like the competition that ends up driving frac sand prices down. The run on Texas is a big one:

“The costs are really low of producing this sand and of course they’re putting up too many mines, which basically means that they could sell that sand for as little as $30 a ton,” Wisconsin Public Radio quoted IHS oilfield services expert Samir Nangia as saying.

Producers love it because, according to Nangia, it costs up to $60 a ton just to ship Wisconsin frac sand to Texas by rail.

"These Permian mines are going to take market share away from the Midwest mines but what is also true is that they cannot take away 100 percent of the market share," said Nangia. "If I had to cap it, I would cap it at 50 percent."

It doesn’t necessarily mean that Wisconsin is out of this game, because all sands aren’t equal. The cheese state’s white sand is stronger and lets producers drill deeper and wells produce longer. But according to Nangia, some producers have already been cutting it with the cheaper Texas sand to make it go further.

This Is Frac Sand Boom 2.0

All in all, the ‘mega frac’ is a brilliant price driver for specialty frac sand, which cost about $25 per ton last year, but has been known to hit $70 per ton when supplies are short. And while this is a mouthwatering price for investors, it’s not traded like a commodity, so getting in on it means buying equity in producers themselves.

There aren’t that many public frac sand companies to choose from, either, and this is a pretty consolidated market, led for the most part by U.S. Silica, Fairmount Santrol, and Hi-Crush Partners LP, which together corner over 45 percent of market share.

And according to a new Market Study Report, the global frac sand market is expected to grow at a CAGR of around 14.7 percent over the next five years, reaching $6.7 billion in 2023, up from around $2.9 billion last year.Related: Record Oil Production Doesn’t Free U.S. From Global Market

For anyone betting on oil, frac sand shouldn’t be far behind—but it hasn’t always followed the same pattern. It went bust in a bad way in 2014 when oil did, and saw a revival in 2016—before oil prices responded upwards. That’s because producers started increasing the size of wells (bigger fracs), even if the number of wells wasn’t going anywhere. So, in 2016, the new frac sand boom preceded an oil rebound.

And look to Texas, because the frac sand mining set-up is about to get even easier. Kinder Morgan is planning a new gas pipeline to West Texas that will ease a major bottleneck for oil and gas producers. That heralds yet another uptick in frac sand demand once it’s up and running as slated in 2019. The $1.75-billion line will connect the Permian to eastern Texas and is scheduled to begin operations in October next year.

Right now, prices for natural gas that pipeline bottlenecks have trapped in the Permian are lower than pretty much any other major American hub. Output may be booming, but prices are down 30 percent from a year ago because it’s all trapped.

Once the bottlenecks are sorted out, we’ll see Frac Sand Boom 3.0, and it’s going to be all about Texas.

By Julianne Geiger for Oilprice.com

The ‘mega-frac’ is turning the typically annoying sand of West Texas into the new gold, and the oil and gas land rush on the Permian Basin has now extended into the dry, gritty sand that only a year ago few would have given a second thought.

While most are busy watching all land grabs by oil and gas producers in the Permian, much less attention has been paid to the secondary land rush for the sandy wasteland that could ease some of the bottlenecks for producers who need frac sand to make anything happen.

Now as some herald a new phase of deal-making and consolidation following the Permian oil and gas land rush, the same may end up happening for all those frac sand producers who have followed them there.

As many as 23 new frac sand mines are being developed in West Texas this year, according to reports cited by Bloomberg.

Why Texas, And How Much Frac Sand Do We Really Need?

The process of hydraulic fracturing involves injecting highly pressurized water into a well and then pouring sand into it in order to keep the tiny fractures created by the water blast open. After that, the holes are widened to allow the crude to ooze out of the shale rock. The more fractures created in a rock, the more oil and gas producers will get out of it. That notion of well completion intensity is driving increasing sand usage per well.

It’s all put the frack sand subsector very much on investor radar as a backdoor into the lucrative shale business. So much so, in fact, that some have even started referring to the frac sand situation as “proppant-geddon”.

So the answer to ‘why Texas’ is a simple one: Frac sand producers follow the oil producers, and they’re descending on the Permian. And until the run on Texas sand, producers were largely dependent on expensive ‘white sand’ mined in Wisconsin and Minnesota. The brown sand of Texas is cheaper. And when it’s right in your backyard, producers save a bundle.

It’s cheaper because it’s easier to mine. Wisconsin’s sand is locked up in sandstone, while Texas’ is just hanging out in big dunes. That’s where the lower price comes into play.Related: The Best And Worst Oil Price Predictions

Of course, it’s bad news for Wisconsin, which won’t like the competition that ends up driving frac sand prices down. The run on Texas is a big one:

“The costs are really low of producing this sand and of course they’re putting up too many mines, which basically means that they could sell that sand for as little as $30 a ton,” Wisconsin Public Radio quoted IHS oilfield services expert Samir Nangia as saying.

Producers love it because, according to Nangia, it costs up to $60 a ton just to ship Wisconsin frac sand to Texas by rail.

"These Permian mines are going to take market share away from the Midwest mines but what is also true is that they cannot take away 100 percent of the market share," said Nangia. "If I had to cap it, I would cap it at 50 percent."

It doesn’t necessarily mean that Wisconsin is out of this game, because all sands aren’t equal. The cheese state’s white sand is stronger and lets producers drill deeper and wells produce longer. But according to Nangia, some producers have already been cutting it with the cheaper Texas sand to make it go further.

This Is Frac Sand Boom 2.0

All in all, the ‘mega frac’ is a brilliant price driver for specialty frac sand, which cost about $25 per ton last year, but has been known to hit $70 per ton when supplies are short. And while this is a mouthwatering price for investors, it’s not traded like a commodity, so getting in on it means buying equity in producers themselves.

There aren’t that many public frac sand companies to choose from, either, and this is a pretty consolidated market, led for the most part by U.S. Silica, Fairmount Santrol, and Hi-Crush Partners LP, which together corner over 45 percent of market share.

And according to a new Market Study Report, the global frac sand market is expected to grow at a CAGR of around 14.7 percent over the next five years, reaching $6.7 billion in 2023, up from around $2.9 billion last year.Related: Record Oil Production Doesn’t Free U.S. From Global Market

For anyone betting on oil, frac sand shouldn’t be far behind—but it hasn’t always followed the same pattern. It went bust in a bad way in 2014 when oil did, and saw a revival in 2016—before oil prices responded upwards. That’s because producers started increasing the size of wells (bigger fracs), even if the number of wells wasn’t going anywhere. So, in 2016, the new frac sand boom preceded an oil rebound.

And look to Texas, because the frac sand mining set-up is about to get even easier. Kinder Morgan is planning a new gas pipeline to West Texas that will ease a major bottleneck for oil and gas producers. That heralds yet another uptick in frac sand demand once it’s up and running as slated in 2019. The $1.75-billion line will connect the Permian to eastern Texas and is scheduled to begin operations in October next year.

Right now, prices for natural gas that pipeline bottlenecks have trapped in the Permian are lower than pretty much any other major American hub. Output may be booming, but prices are down 30 percent from a year ago because it’s all trapped.

Once the bottlenecks are sorted out, we’ll see Frac Sand Boom 3.0, and it’s going to be all about Texas.

By Julianne Geiger for Oilprice.com

SEE https://plawiuk.blogspot.com/search?q=FRAC

SEE https://plawiuk.blogspot.com/search?q=FRACKING

SEE https://plawiuk.blogspot.com/search?q=SAND

SEE https://plawiuk.blogspot.com/search?q=FRAC+SAND

No comments:

Post a Comment