A virus called Wuhan-400 causes outbreak … in a Dean Koontz thriller from 1981. How is it that some books appear to prophesy events?

The Eyes of Darkness features a Chinese military lab in Wuhan that creates a virus as a bioweapon; civilians soon become sick after accidentally contracting it

In fact, the one lab in China able to handle the deadliest viruses is in Wuhan and helped sequence the novel coronavirus the world is currently battling

Kate Whitehead

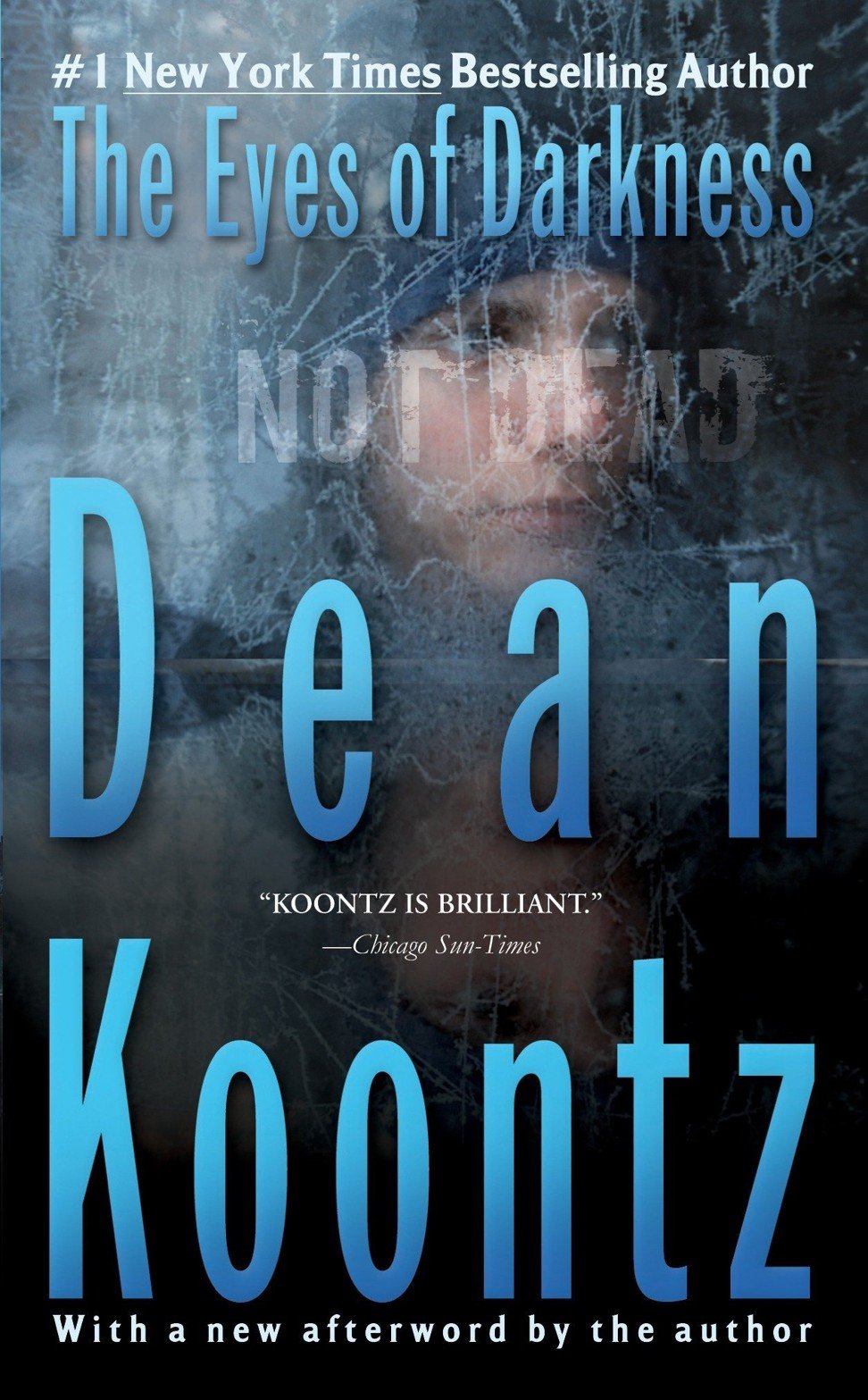

In bestselling suspense author Dean Koontz’s 1981 thriller The Eyes of Darkness, a virus to be used as a biological weapon is developed in Wuhan, China, but humans end up contracting it. Photo: Shutterstock

The Eyes of Darkness, a 1981 thriller by bestselling suspense author Dean Koontz, tells of a Chinese military lab that creates a virus as part of its biological weapons programme. The lab is located in Wuhan, which lends the virus its name, Wuhan-400. A chilling literary coincidence or a case of writer as unwitting prophet?

In The Eyes of Darkness, a grieving mother, Christina Evans, sets out to discover whether her son Danny died on a camping trip or if – as suspicious messages suggest – he is still alive. She eventually tracks him down to a military facility where he is being held after being accidentally contaminated with man-made microorganisms created at the research centre in Wuhan.

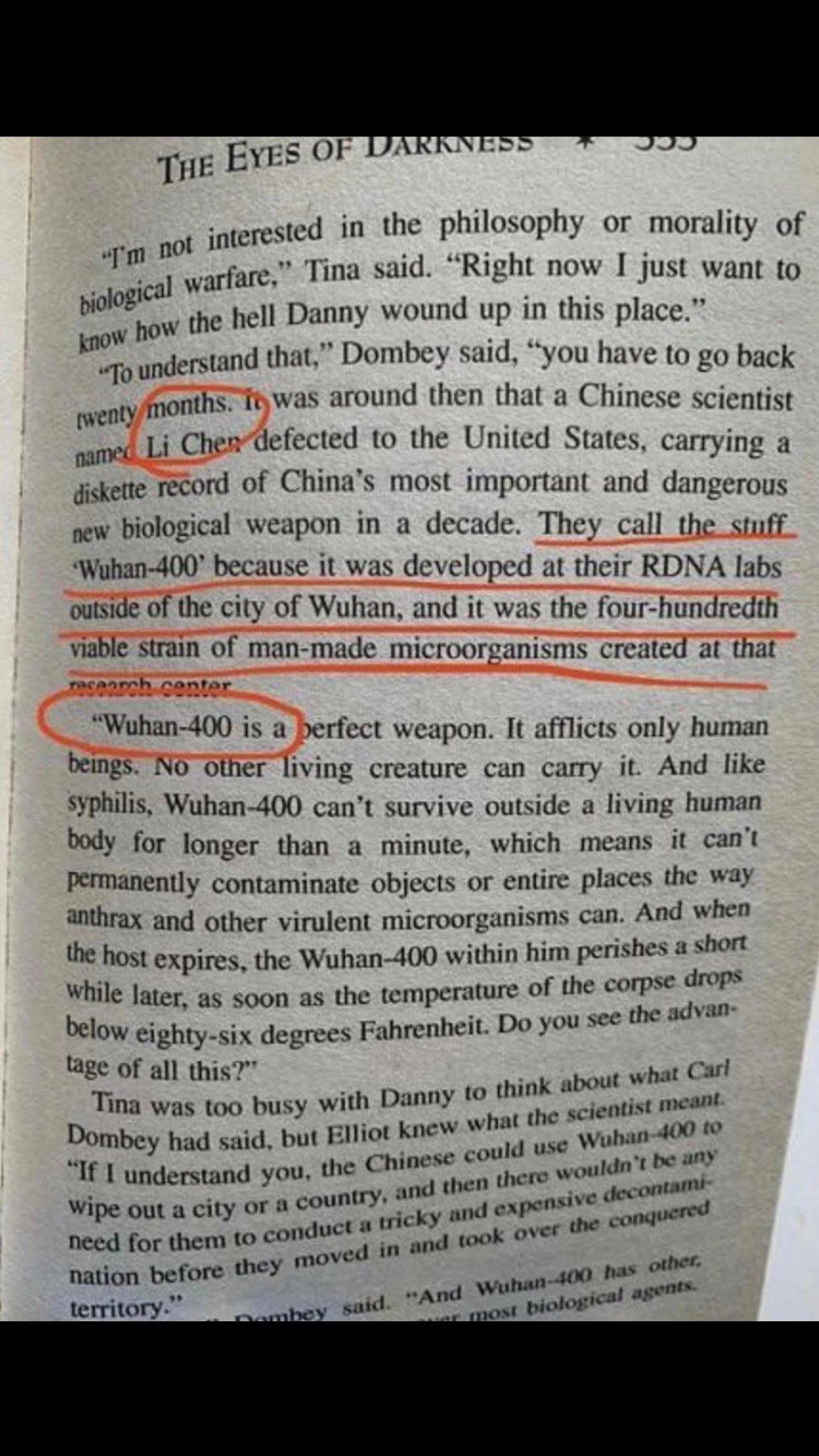

If that made the hair on the back of your neck stand up, read this passage from the book: “It was around that time that a Chinese scientist named Li Chen moved to the United States while carrying a floppy disk of data from China’s most important and dangerous new biological weapon of the past decade. They call it Wuhan-400 because it was developed in their RDNA laboratory just outside the city of Wuhan.”

In another strange coincidence, the Wuhan Institute of Virology, which houses China’s only level four biosafety laboratory, the highest-level classification of labs that study the deadliest viruses, is just 32km from the epicentre of the current coronavirus outbreak. The opening of the maximum-security lab was covered in a 2017 story in the journal Nature, which warned of safety risks in a culture where hierarchy trumps an open culture.

Chinese research lab denies links to first coronavirus patient

17 Feb 2020

Fringe conspiracy theories that the coronavirus involved in the current outbreak appears to be man-made and likely escaped from the Wuhan virology lab have been circulated, but have been widely debunked. In fact the lab was one of the first to sequence the coronavirus.

In Koontz’s thriller, the virus is considered the “perfect weapon” because it only affects humans and, since it cannot survive outside the human body for longer than a minute, it does not demand expensive decontamination once a population is wiped out, allowing the victors to roll in and claim a conquered territory.

It’s no exaggeration to call Koontz a prolific writer. His first book, Star Quest, was published in 1968 and he has been churning out suspense fiction at a phenomenal rate since with more than 80 novels and 74 works of short fiction under his belt. The 74-year-old, a devout Catholic, lives in California with his wife. But what are the odds of him so closely predicting the future?

Albert Wan, who runs the Bleak House Books store in San Po Kong, says Wuhan has historically been the site of numerous scientific research facilities, including ones dealing with microbiology and virology. “Smart, savvy writers like Koontz would have known all this and used this bit of factual information to craft a story that is both convincing and unsettling. Hence the Wuhan-400,” says Wan.

British writer Paul French, who specialises in books about China, says many of the elements around viruses in China relate back to the second world war, which may have been a factor in Koontz’s thinking.

The Eyes of Darkness, by Koontz.

“The Japanese definitely did do chemical weapons research in China, which we mostly associate with Unit 731 in Harbin and northern China. But they also stored chemical weapons in Wuhan – which Japan admitted,” says French.

Publisher Pete Spurrier, who runs Hong Kong publishing house Blacksmith Books, muses that for a fiction writer mapping out a thriller about a virus outbreak set in China, Wuhan is a good choice.

“It’s on the Yangtze River that goes east-west; it’s on the high-speed rail [line] that goes north-south; it’s right at the crossroads of transport networks in the centre of the country. Where better to start a fictional epidemic, or indeed a real one?” says Spurrier. (Spurrier works part-time as a subeditor for the Post.)

Albert Wan runs the Bleak House Books store in San Po Kong, Hong Kong.

Hong Kong crime author Chan Ho-kei believes that this kind of “fiction-prophecy” is not uncommon.

“If you look really hard, I bet you can spot prophecies for almost all events. It makes me think about the ‘infinite monkey’ theorem,” he says, referring to the theory that a monkey hitting keys at random on a typewriter keyboard for an infinite amount of time will almost surely type any given text.

“The probability is low, but not impossible.”

British writer Paul French.

Chan points to the 1898 novella Futility, which told the story of a huge ocean liner that sank in the North Atlantic after striking an iceberg. Many uncanny similarities were noted between the fictional ship – called Titan – and the real-life passenger ship RMS Titanic, which sank 14 years later. Following the sinking of the Titanic, the book was reissued with some changes, particularly in the ship’s gross tonnage.

“Fiction writers always try to imagine what the reality would be, so it’s very likely to write something like a prediction. Of course, it’s bizarre when the details collide, but I think it’s just a matter of mathematics,” says Chan.

Many of Koontz’s books have been adapted for television or the big screen, but The Eyes of Darkness never achieved such glory. This bizarre coincidence will thrust it into the spotlight and may see sales of this otherwise forgotten thriller jump.

Hong Kong crime author Chan Ho-kei.

Amazon is currently offering it on Kindle for just US$1. Perhaps, like Futility, it will also be reissued with some updates to make it really echo the current outbreak.

China wasn’t original villain in book ‘predicting’ coronavirus outbreak – it was Russia

Dean Koontz’s The Eyes of Darkness originally contained details of a man-made virus called Gorki-400 from the Russian city of Gorki

The change to Wuhan came when the book was released in hardback under Koontz’s own name in 1989 – at the end of the Cold War

Kate Whitehead

Much has been made of Dean Koontz’s 1981 book The Eyes of Darkness which appeared to have predicted the recent coronavirus outbreak – but the original villain was Russia, not China. Photo: Shutterstock

The 1981 book by US thriller writer Dean Koontz that appeared to predict the coronavirus outbreak in China initially had the virus originating in Russia.

The book appears to have been rewritten after the collapse of the Soviet Union meant the country was no longer seen as a communist bogeyman.

Koontz’s The Eyes of Darkness made headlines in the past week after readers noted the story concerned a man-made virus called Wuhan-400 developed in a biological weapons lab in Wuhan – ground zero of the current coronavirus outbreak – and described as the “perfect weapon”.

“They call the stuff ‘Wuhan-400’ because it was developed at their RDNA labs outside the city of Wuhan, and it was the four-hundredth viable strain of man-made organisms created at that research centre,” Koontz writes in the book.

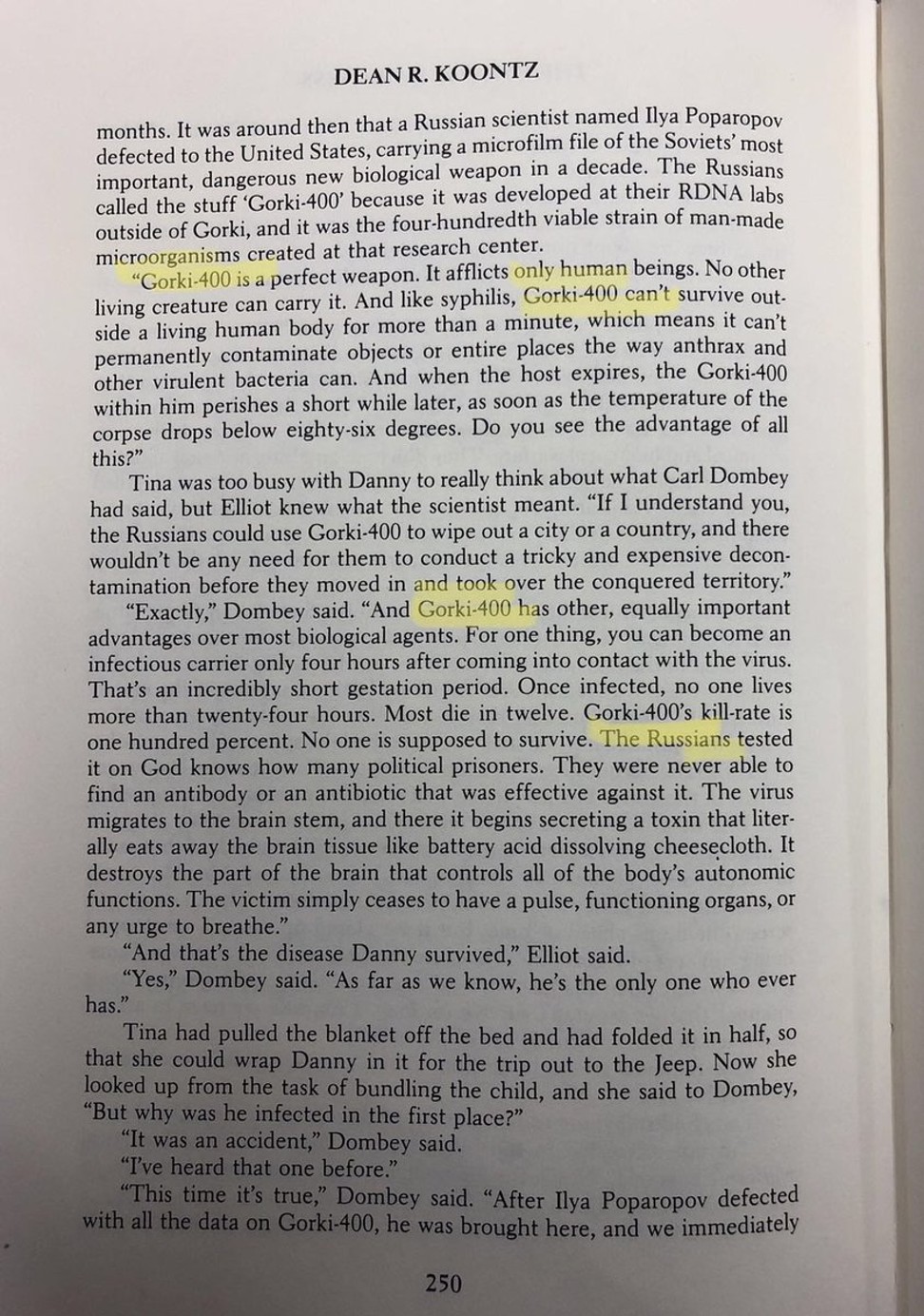

However, Wuhan wasn’t even originally mentioned in The Eyes of Darkness. The first edition of the book, written under Koontz’s pseudonym Leigh Nichols, concerns a virus called Gorki-400 that was created by the Russians and emerged from “the city of Gorki”.

Excerpt from 1981 edition of The Eyes of Darkness.

The change to Wuhan came when the book was released in hardback under Koontz’s own name in 1989. The year of the book’s re-release is significant – 1989 marked the

end of the Cold War. And with the collapse of the Soviet Union, the country was no longer communist.

“Starting in 1986, relations between the US and the Soviet Union began improving,” says Jenny Smith, co-founder of indie bookshop Bleak House Books in Hong Kong and a student of Russian history. “Mikhail Gorbachev came in in 1985 and was very interested in making the Soviet Union a more open society and improving relations. By 1988, it is our friend and not our enemy.”

Cover of the 1981 edition of The Eyes of Darkness.

An American author pointing the fictional finger of blame at Russia would not have gone down well in that climate, so The Eyes of Darkness needed a new villain. There were only so many places with bio-weapons facilities – think France, Britain and Japan – and most, as far as the US was concerned, were the good guys.

“China is the only place that comes to my mind that would have had an active programme and it’s likely there was a deep suspicion [in the US] of China covering a lot of things in this period,” says Smith, who wrote her PhD on Soviet technology at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in the United States.

This was in the immediate aftermath of the 1989 student demonstrations and the bloody Tiananmen crackdown that followed. It was a period when there were rumours swirling about leaks and cover-ups at biological weapons facilities, says Smith, and the US would have been aware of the repression of these rumours.

Excerpt from a post-1989 edition of The Eyes of Darkness.

The switch from Gorki-400 to Wuhan-400 in the book was a literal cut-and-paste and appears to reflect the shift in mentality after the Cold War.

“Everyone was thinking in terms of two great powers – America and the Soviet Union, the good guys and the bad guys. It’s easy to see how you might substitute one bad guy for another, Gorki for Wuhan,” says Smith.

It is not known whether Koontz himself requested this change or his publisher made it. Emails to Koontz, his literary agent and publisher have gone unanswered.

Author Dean Koontz in 2019. Photo: Douglas Sonders

Leigh Nichols wasn’t the only pen name Dean Koontz wrote under in his early career. He also used David Axton, Deanna Dwyer and K.R. Dwyer.

“It’s not unusual to use a pen name when you are starting off in your career. To play it safe, you don’t want to be as exposed,” says Albert Wan, Smith’s husband and the co-founder of Bleak House Books. “When his books started to take off in popularity, he may well have decided to use real identity.”

As for the Gorki referenced in the book, it could be one of a number of Russian towns with that name. The largest, just south of Moscow, is home to 3,500 people today. Compare that with Wuhan, with its population today of more than 11 million – even in 1989, Wuhan’s population topped 3.3 million.

The revised edition of The Eyes of Darkness brought the book closer to possibility, but it’s still some way off what’s happening with

Covid-19. Significantly, contracting the fictional Wuhan-400 is a certain death sentence, while only 2 per cent of Covid-19 cases are fatal.

Jenny Smith is a co-founder of indie bookshop Bleak House Books.

“It might run as science fiction, but it’s not impossible as it has happened in the past and people would be aware of it,” Smith says. “Think of the cover-up over anthrax – a lot of these stories are stranger than real life.”

Meanwhile, readers are also pointing to a passage in a book by the late Sylvia Browne, an American author who claimed to be psychic, that predicted an international outbreak of a virus this year.

“Around 2020, a severe pneumonia-like illness will spread throughout the globe, attacking the lungs and the bronchial tubes and resisting all known treatments,” Browne wrote in the book End of Days. “Almost more baffling than the illness itself will be the fact that it will suddenly vanish as quickly as it arrived, attack 10 years later, and then disappear completely.”

Kate Whitehead is a freelance journalist who worked on staff at the SCMP before editing Discovery magazine. She is the author of two Hong Kong crime books - After Suzie and Hong Kong Murders - and fully intends that the next book she writes will be less grisly.

No comments:

Post a Comment