“True Detective”: Down the Bayou (Far From Any Road)

By Jacob Mikanowski MARCH 8, 2014

SINCE IT BEGAN airing eight weeks ago, True Detective, HBO’s new murder-mystery anthology series, has enthralled viewers like few shows in recent memory. And small wonder. It’s unlike anything that’s been on television for a long time. In some ways, it superficially resembles other programs in the criminal investigation genre, like Jane Campion’s superb Top of the Lake, BBC’s overwrought The Fall, and FX’s profoundly under-thought The Bridge. But none of those shows share True Detective’s gothic sensibility and narrative complexity. Set in (at least) three time periods, True Detective’s central mystery, the ritualistic killing of a prostitute named Dora Lange, is never its only enigma. The twists and turns in the lives of its main characters, detectives Rust Cohle and Marty Hart — their relationships, their pasts, even the true nature of their identities — remain as compelling as the whodunit at the heart of the story. And then there’s the dialogue, especially Rust Cohle’s, as played by Matthew McConaughey: sinuous digressive soliloquies that touch on everything from applications of string theory to the Nietzschean doctrine of eternal recurrence. They’re as baroque as anything in Deadwood when David Milch was writing it and as weird as anything in Twin Peaks. Just hearing some of this stuff on TV — from the doctrine of anti-natalism to shout-outs to the transgressive horror fiction of Thomas Ligotti to the apocalyptic philosophy of Emil Cioran — is shocking. It’s as if an invisible cultural wall had suddenly been breached, like what would happen if Wisconsin Public Radio ever did a program on the Necronomicon. All of a sudden the psychosphere is in the mainstream.

None of this on its own, though, accounts for the heights of obsessive viewership True Detective has inspired. That has more to do with, on one hand, the strength of the lead performances, and on the other, with the bevy of obscure literary references placed in the script by series creator Nic Pizzolatto. McConaughey and Harrelson are both riveting in their separate ways (not that they have many rivals on the show; in impact and in screen time they dwarf the other players — though Ginger, the red-haired beard-braid wearing biker from Episode 4 is hard to ignore, and Reggie Ledoux certainly makes an impression). McConaughey especially is extraordinary, creating a distinct persona for each time period and succeeding in conveying the impression that he’s at once unsure of his sanity and invariably the smartest man in the room. Harrelson, as his foil, sets off fewer fireworks but still succeeds in garnering sympathy for a character who, especially in the season’s first half, seemed as brutish as he is conventional.

But while the lead actors keep you watching, it’s the trail of allusive breadcrumbs and narrative trapdoors that have transformed criticism of the show into a paranoid art. Repeated mentions of black stars and the mythical city of Carcosa have sent thousands of watchers (myself included) hustling after copies of Robert W. Chambers’s 1895 volume of moody decadent-era horror stories, The King in Yellow; its central motif is a fictional play whose first act makes you curious and whose second act drives you mad. With one episode left, nothing seems more important than knowing the identity of the Yellow King, the shadowy figure who may or may not be Dora Lange’s killer as well as the leader of a sinister cult responsible for a decades-long chain of related killings. That is, unless he’s a rare psychotropic drug or the name of the victim in a ritual sacrifice, or a Cthulhu-esque horror from the outer depths.

Tracking these Easter eggs and clues is undeniably fun, but I think that focusing too much on them might be a mistake. After all, not all of a show’s significance resides in its script. What’s so remarkable about True Detective is the way all the various visual and aural elements in it — the music, the cinematography, the set design, even the filming locations and the history they contain — interlock to contribute to its meaning. To grasp the whole requires taking a look at each of the parts. Doing so reveals a show that isn’t just a mystery or a crime drama, but something more akin to a murder ballad or myth: a work of art whose references cover a startling range of territory and whose resonances reach deep into the American past.

So, begin at the beginning, with the credits. In a way, the song chosen by T Bone Burnett for the title sequence, the Handsome Family’s “Far From Any Road,” contains the whole series in miniature. As I hear it, the song recalls a murder. This puts it in line with ballads like “The Bramble Briar,” “In the Pines,” and “Omie Wise” — folk songs with deep roots, set in wild places, each with violent death at its center. And, like another early ballad — “Barbara Allen” — it’s a story of transfiguration, as well. “Far from any Road” takes place in a wilderness full of rattlesnakes and mountain lions. A man has gone there in search of a night-blooming cactus. The cactus, like the briar in “Barbara Allen,” is the soul of a dead woman — and in this transformation, she echoes the burning bushes in the Aeneid, and the talking grove in the Inferno:

She twines her spines up slowly

Towards the boiling sun

And when I touched her skin

My fingers ran with blood

She might have been the man’s lover, or his victim. Quite possibly both. In the desert, the man dies. Together, their souls are swept up above the silent sands.

The song then opens up the show in more ways than one. It creates a landscape: death and nature; dead women, deadly men; wild places and the spirits inside of things. And if the interpretation above seems far-fetched (it certainly isn’t definitive), it might be worth remembering that the Handsome Family’s work is steeped in the traditions of American folk music, which they brilliantly adapt into a new mode, and that Rennie Sparks, the lyricist, comes armed with a deep knowledge of folklore and myth. In The Rose & the Briar, a collection of essays on American ballads edited by Greil Marcus and Sean Wilentz, she contributes a piece on the song “Pretty Polly.” The essay roams widely across time and space, gathering up everything from serial killers, Salem witch trials, to pagan rituals and Goddess cults in a search for the murder ballad’s meaning. Here’s Sparks, drawing all the threads together:

These killers are invisible men, desperate for meaning and vision, for beauty and sacredness, but unable to see even their own hands without first drenching them in blood. I believe “Pretty Polly” is a magic spell written to dispel the deadness of the heart […] It is a ritual of bloodletting, an appeal to invisible forces, a cry to the goddess to come embrace us with her thorny arms. Polly’s murder works as Joseph Campbell believed all myth worked — as a secret opening, a knife slashed in the veil of experience through which deep knowledge may seep. To those not gifted enough to hear the bean plants talk or to see the fairies dancing, myth may be our only access to places outside our conscious perception of reality.

In Sparks’s telling, the story of the song — of a dead girl killed in the forest sometime in the American past — is an ancient one, reaching right back to the beginnings of American history and even to the origins of religion itself. The murdered woman is sacred, she argues, an emblem of a goddess of nature and chaos and, at the same time, a sacrifice to the male desire to possess beauty and destroy it.

Something similar happens on True Detective. The first thing we see in the first episode of the show is the body of a girl, carried by a man in darkness. Soon, fire spreads across the cane fields. The next day we meet the detectives and see what’s been done to her. Dora Lange (though we won’t learn her name for a while) has been posed beneath a tree, stabbed multiple times in the abdomen, and — most strikingly — made to wear a crown of deer antlers.

If the placement of Dora’s body — seemingly merged with a tree, her body in a kind of weird harmony with surrounding landscape — links the show to old murder ballads, the antlers connect it to something a lot more modern. Or at least, they seem to. Antlers are a bit of a serial-killer cliché (albeit a relatively new one). They feature heavily in Hannibal, the NBC Silence of the Lambs-prequel series which, although stylishly-shot and featuring intriguing performances, feels like dropping six levels in ambition and intelligence when watched alongside True Detective. (It has, nonetheless, broached new frontiers in the art of food-styling on TV and in the process become a runaway hit on Tumblr. True Detective: Top Chef feels like the logical next step). Cliché or not, horns go deep. The coroner on Episode 1 tells Hart and Cohle that the ceremonial presentation of Dora’s body reminds him of Paleolithic cave art, and he suggests that the two of them to talk to an anthropologist. They don’t, but I took his advice and reached for my copy of Georges Bataille’s The Cradle of Humanity: Prehistoric Art and Culture. Here’s what I found:

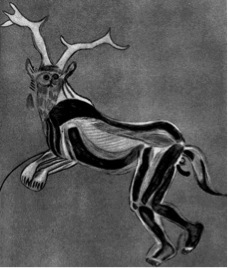

Henri Breuil, sketch of the “Sorcerer” from the cave of Trois-Frères, France

It’s a figure engraved in the cave of Les Trois-Frères in Southern France. It was sketched by the Abbé Breuil, the great pioneer of the study of prehistoric art, who first saw the image by flickering lamplight and persuaded himself that it was a god. Breuil described the figure as having the ears and horns of a stag. Bataille thought he was the original shaman, carved at the moment when man separated from the animals and began to search for deities. Margaret Murray, early proponent of the witch-cult hypothesis, thought he was the first instance of the Horned God, whose cult she saw stretching across Eurasia and lurking behind the witches’ Sabbaths of the Middle Ages.

Never mind that what Breuil saw in that cave has never been seen the same way since, or that Murray’s theories have long been discredited. Once you start looking, Horned Gods are everywhere. They turn up all over the place, especially on the fringes of religious history. As Cernunnos, the horned Celtic God, identified on a single carving from ancient Lutèce. As the Lord of Animals from the Gundestrup Cauldron. As Baphomet, the Templars’s goat. In the myth of Artemis and the stag. In “The Wild Hunt.” In True Detective, the Horned God seems to have something to do with the powerful Tuttle Family and their “very rural take” on Mardi Gras, apparently derived from the real-life Cajun traditions of the Courir de Mardi Gras, with its masked mummers and costumed masked riders wearing cone-shaped capuchon hats (briefly seen in a photograph in Dora Lange’s mother’s home). Those traditions in turn tie into a whole web of beliefs surrounding post-Lenten inversion, and pagan, pre-Christian Saturnalia. All throughout, the same tropes crop up again and again: rituals of fertility, confusion between the worlds of animal and man, beliefs that stray into blasphemy and sacrifice and a landscape populated by spirits.

Dora Lange Horned God, Gundestrup Cauldron (c. 200 BC)

One of the things that is so distinctive about True Detective is the way it makes landscape into a character. Much of that has to do with Adam Arkapaw’s painterly, assured cinematography. Before True Detective, Arkapaw worked on Top of the Lake, the Campion-directed miniseries about a vanished child and sexual abuse in a small Southern New Zealand town. Many things about that show were excellent: the lead performances from Elisabeth Moss and Peter Mullan; its ability to explore vulnerability and sexual need in the confines of what was essentially a procedural; Campion’s daring in portraying an embattled attempt at feminist utopia; her ability to infuse all the episodes with mix of compassion and slow-simmering dread. But watching it, I frequently became as enthralled by the scenery as anything else. After binge-watching on Netflix, I’d find myself using Google Maps to explore the locations featured on the show, virtual-strolling around Glenorchy and Lake Wakatipu. I couldn’t get enough from the episodes alone. I wanted to linger.

The same is true with True Detective. The show has gone to so many places I want to revisit: the biker bar outside of Beaumont; that field outside Erath; the crab-fishing village from Episode 3; whichever bars in Louisiana are continuously playing old Waylon Jennings and Kris Kristofferson songs. A lot has been said about the virtuoso camerawork on True Detective, especially the heart-stopping six-minute tracking shot during the raid to the stash house in Episode 4. And the direction is remarkable for the number of times it will find an unusual perspective from which to film — from behind Rust Cohle’s busted taillight, for instance — or locate a point of interest in the margins, as in the strange and poetic shot of men pushing the detective’s car after the sequence in the revival tent.

What I might like the most, though, is when the camera lifts away from the main action and turns to the backdrop, like in the arcing crane shot at the end of Episode 7. When the camera finishes circling around the cemetery being mowed by the newly-revealed scarred main suspect (and I loved the way the setting sun was used to conceal his scars until the last moment), it lifts off to take in the sweep of the surrounding waterlogged countryside of tugboats and marshes, to the sound of Townes Van Zandt’s “Lungs.” At this moment, as at other times when the camera pauses on any of the countless petrochemical refineries the detectives drive by, the photography reminds me of work by Richard Misrach. Specifically, it calls to mind Petrochemical America, his series of photos chronicling the environmental degradation of the part of the lower course Mississippi River nicknamed Cancer Alley.

Richard Misrach, Sugar Cane and Refinery, Mississippi River Corridor, 1998

Staring out the car window, Cohle says at one point: “This pipeline is carving up the coast like a jigsaw. Place is gonna be underwater in 30 years.” And here is Misrach describing one of his photographs:

The industrial pipeline’s backdrop of swampland and twisted trees is a cameo of the tropical ecology that functions like a sponge for effluents from petrochemical waste. Since the 1930s, oil companies have routed an estimated twenty-six thousand miles of pipeline throughout the oil-laden Southern parishes and across the Southern coastal wetlands. A web of canals has been cut through pastures and marshlands. The resulting erosion has been striking, with an area of wetlands the size of Delaware swallowed by the Gulf of Mexico.

Like Misrach’s photography, the cinematography draws attention to southern Louisiana as a wounded landscape, hurt both by the introduction of the oil refining business and the continued human management of the Mississippi River, whose corralling behind levees has doomed the region to a slow death by subsidence.

True Detective isn’t a documentary though, and it draws on the work of other artists to create the gothic atmosphere of the show, which, after all, has more to do with Manly Wade Wellman Appalachian pulp than with John McPhee’s The Control of Nature. Grantland’s Molly Lambert has described the way in which it has made use of the horror-fiction illustrations of fantasy artist Lee Brown Coye for the strange wooden-lattice structures that mark many of the crime scenes. Coye’s work, “based on a childhood experience where he found sticks set up in strange ways at an abandoned farmhouse,” led him to create a whole mythology around the mysterious shrines. Their presence on the show adds a whole dimension of paranoia to the detectives’ exploration of the landscape (the suggestion that these objects were thick on the ground after Katrina is especially chilling). The same is true for the stick sculptures scattered around Louisiana by the Carcosa-cultists. They look like deliberate imitations of the work of the British landscape artist Andy Goldsworthy, and it’s amazing how much menace the set designers manage to imbue into his otherwise bland-as-milk evocations of the English countryside.

Andy Goldsworthy

Andy GoldsworthyIt makes me wonder what else they could do with Land Art on the show. (Does is matter that the oldest prehistoric earthwork in North America is at Poverty Point Louisiana? That Land Artist Michael Heizer makes similar temple-like earthworks in the Nevada desert? That Heizer’s father, Robert, was an archaeologist who investigated depictions of human sacrifice in Mexico? That Heizer’s friend and rival was Robert Smithson, and that Smithson’s most famous work, the Spiral Jetty, is a giant stone spiral half-submerged in the Great Salt Lake? Is Robert Smithson the Yellow King?)

Robert Smithson, Spiral Jetty (1970)

Robert Smithson, Spiral Jetty (1970)The Southern Louisiana of True Detective is part truth and part myth. But just by showing so much of it, the show puts us in contact with its real history, even if it doesn’t spell everything out. But there are hints, especially on the margins. There’s the history of pollution, visible in the omnipresent cracking towers and in the condition of Dora Lange’s mother as well as the relative of another victim, a one-time baseball pitcher disabled by a series of strokes. There’s Louisiana’s French and Spanish past, glimpsed momentarily in the Courir and in a stray allusion by Rust to the Pirate Republic of Barataria. And then there’s the history of segregation and racism, barely present except for the suggestion that the schools most of the victims attended were a way around busing — like the “segregation academies” that sprang up in different parts of the Deep South as a response to Brown vs. the Board of Education.

In my dream version of the show, the detectives are historians or archivists. They could work equally well somewhere in the Mississippi Delta or Eastern Poland. The crimes they investigate are buried in the past, and the thing they realize eventually isn’t just that everyone knew, but that everyone was complicit. Coincidentally, while the first episodes aired, I happened to be reading Trouble in Mind, Leon Litwack’s magisterial history of the lives of Black Southerners under Jim Crow. And although I shouldn’t have been, I was shocked by his account of lynching — at how common it was, how popular, and how public. The audiences that gathered for lynchings were huge, and their appetite for suffering — burning and other tortures — as spectacle couldn’t be satisfied by mere killing. Children even played their own games of hanging and being hung. True Detective doesn’t go there — but in the sense it creates, of a past that infects the present, of ritualized violence that doesn’t end even after it officially disappears — it starts to open the door.

For some viewers, True Detective never gets past the limits of its cop-show roots. To Grantland’s Andy Greenwald, the show only works when it focuses on actual detective work. Otherwise it’s a pretentious mess, a clichéd, anguished male-psychodrama in which “darkness isn’t a stand-in for depth or maturity.” For The New Yorker’s Emily Nussbaum, it’s more of the same old thing: “macho nonsense” and “dorm-room deep talk,” a triumph of style over substance, an “ominous atmosphere” covering up a “phony duet.”

It’s certainly possible to see True Detective as nothing more than a collection of tics and gestures — an assembly of country songs, attractive photographs, and loopy speeches, overlaid with some oddball philosophy for the illusion of depth. But I don’t think that’s right. I think True Detective, as a whole, is gesturing at something larger. And I think that dismissing something on the basis of style or genre is a mistake. Offbeat genres like murder ballads and B-movie noirs and cop shows allow for the exploration of things that high art can’t attempt: secret histories, submerged passions, primal fears. Pulp is an art of extreme possibility. There’s a reason philosophers gravitate to weirdoes like H.P. Lovecraft, and why songs like “Pretty Polly” have depths that go unplumbed no matter how often they’re sung.

Old forms can conceal deep meanings. True Detective draws on various strains of American horror — rural noir, Lovecraft’s cosmic nightmares, Chambers’s stories of madness and concealed identity. But what it reminds me of most is something older: Nathaniel Hawthorne’s “Young Goodman Brown,” a short story that Melville called deeper than Dante, and that Greil Marcus has invoked in discussing Twin Peaks.

The story is set in Puritan New England — in Salem, Massachusetts, to be exact. In it, Goodman Brown, a pious young man, ventures into the woods one night on an unknown errand, leaving his young wife, Faith, behind in town. On his walk, he meets an older man who looks much like himself, carrying what looks to be a wizard’s staff. The older man knows Brown comes from reputable stock: his grandfather whipped a Quaker woman through the streets of Salem, and his father set fire to Indian villages in King Philip’s War. Not long after, Brown meets another person from town, Goody Cloyse, who reveals herself to be a witch. Soon, Brown is aloft, flying towards an unseen clearing. All the townspeople are there, celebrating in front of a flame-lit altar which may or may not be full of blood. He recognizes a score of church members, “grave, reputable and pious people, elders of the church.” All the people Brown grew up respecting are secretly in the Devil’s company. The old men are wanton seducers; the young women sacrifice infants. Their waking lives are lies. As the assembly readies to baptize its newest members, Brown cries out — and comes to, alone in the forest, not knowing whether what he had seen was a dream. He lives to the end of his days as a broken man. After his death, Hawthorne writes, “they carved no hopeful verse upon his tombstone; for his dying hour was gloom.”

Myth divides the world into the security of civilization and the wilderness of danger. The woods are full of witches and the swamps are full of ghosts. In “Young Goodman Brown,” Hawthorne — whose own ancestors were active in the witch trials — undoes the structure of myth, exposing a deeper terror. The Puritans expected the threat to their spiritual community to come from the surrounding forest. The woods were the space of danger: of Indians, of paganism, of witchcraft, and sin. In “Young Goodman Brown,” Hawthorne tells us plainly that the woods are never outside. The community that seems righteous is always criminal, and complicit. As True Detective heads towards its final episode, it looks increasingly like the Yellow King isn’t Chthulu or a mysterious swamp god. Instead, the perpetrator is a family, its associates, its churches, schools, police officers and public officials and servants and custodians. Evil is woven into the fabric of everyday life. To some, that might be a disappointment. To me, it harks back to the original American horror story: the discovery that the woods are in the town, and the swamp is in our minds.

We’re all in Carcosa now.

¤

Jacob Mikanowski is a graduate student in European History at U.C.Berkeley.

No comments:

Post a Comment