Laura Spinney, Time•March 7, 2020

As the world grapples with a global health emergency that is COVID-19, many are drawing parallels with a pandemic of another infectious disease – influenza – that took the world by storm just over 100 years ago. We should hope against hope that this one isn’t as bad, but the 1918 flu had momentous long-term consequences – not least for the way countries deliver healthcare. Could COVID-19 do the same?

The 1918 flu pandemic claimed at least 50 million lives, or 2.5 per cent of the global population, according to current estimates. It washed over the world in three waves. A relatively mild wave in the early months of 1918 was followed by a far more lethal second wave that erupted in late August. That receded towards the end of the year, only to be reprised in the early months of 1919 by a third and final wave that was intermediate in severity between the other two. The vast majority of the deaths occurred in the 13 weeks between mid-September and mid-December 1918. It was a veritable tidal wave of death – the worst since the Black Death of the 14th-century – and possibly in all of human history.

Flu and COVID-19 are different diseases, but they have certain things in common. They are both respiratory diseases, spread on the breath and hands as well as, to some extent, via surfaces. Both are caused by viruses, and both are highly contagious. COVID-19 kills a considerably higher proportion of those it infects, than seasonal flu, but it’s not yet clear how it measures up, in terms of lethality, to pandemic flu – the kind that caused the 1918 disaster. Both are what are known as “crowd diseases”, spreading most easily when people are packed together at high densities – in favelas, for example, or trenches. This is one reason historians agree that the 1918 pandemic hastened the end of the First World War, since both sides lost so many troops to the disease in the final months of the conflict – a silver lining, of sorts.

Crowd diseases exacerbate human inequities. Though everyone is susceptible, more or less, those who live in crowded and sub-standard accommodation are more susceptible than most. Malnutrition, overwork and underlying conditions can compromise a person’s immune deficiencies. If, on top of everything else, they don’t have access to good-quality healthcare, they become even more susceptible. Today as in 1918, these disadvantages often coincide, meaning that the poor, the working classes and those living in less developed countries tend to suffer worst in an epidemic. To illustrate that, an estimated 18 million Indians died during the 1918 flu – the highest death toll of any country, in absolute numbers, and the equivalent of the worldwide death toll of the First World War.

In 1918, the explanation for these inequities was different. Eugenics was then a mainstream view, and privileged elites looked down on workers and the poor as inferior categories of human being, who lacked the drive to achieve a better standard of living. If they sickened and died from typhus, cholera and other crowd diseases, the reasons were inherent to them, rather than to be found in their often abysmal living conditions. In the context of an epidemic, public health generally referred to a suite of measures designed to protect those elites from the contaminating influence of the diseased underclasses. When bubonic plague broke out in India in 1896, for example, the British colonial authorities instigated a brutal public health campaign that involved disinfecting, fumigating and sometimes burning indigenous Indian homes to the ground. Initially, at least, they refused to believe that the disease was spread by rat fleas. If they had, they would have realized that a better strategy might have been to inspect imported merchandise rather than people, and to de-rat buildings rather than disinfect them.

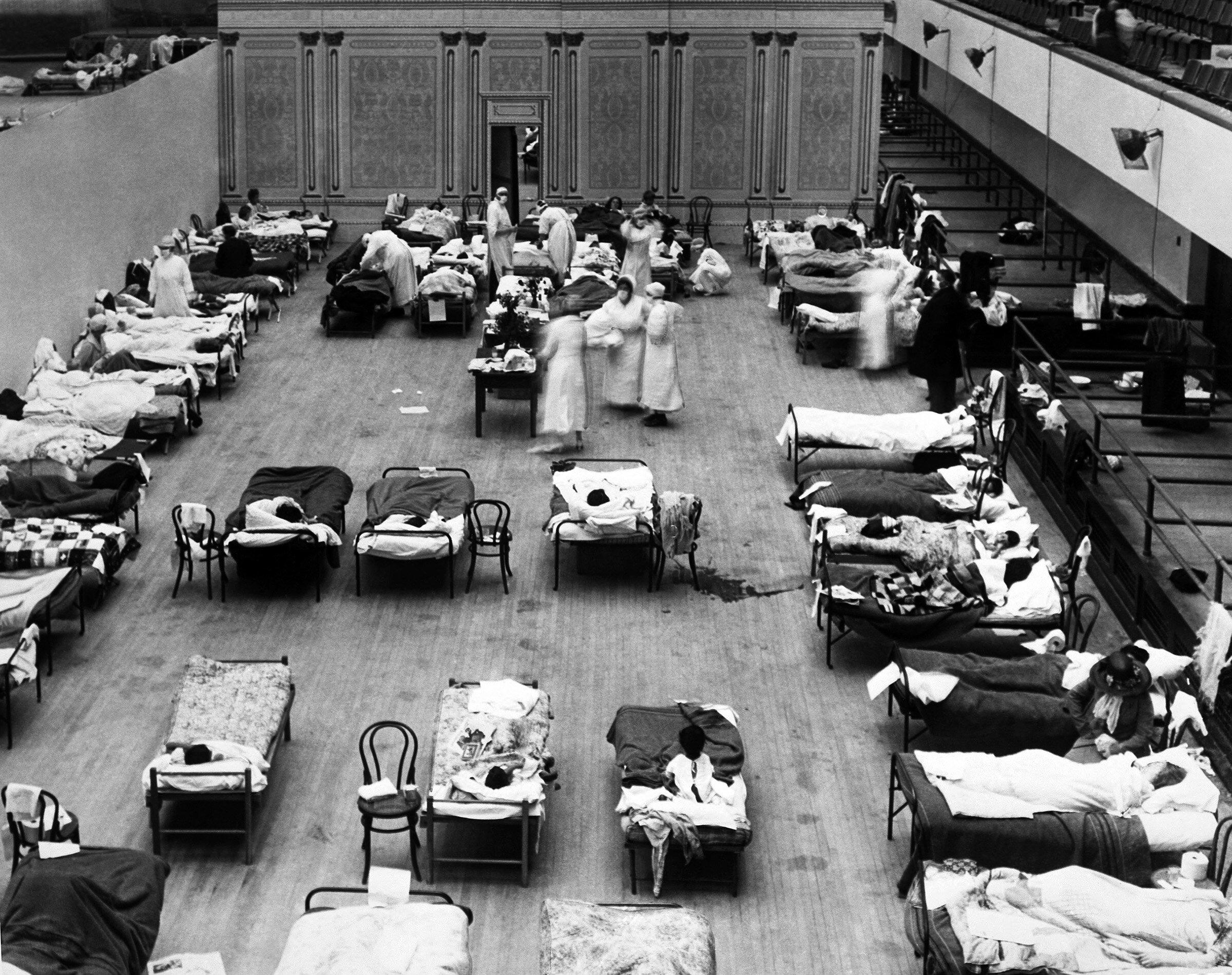

Healthcare was much more fragmented then, too. In industrialized countries, most doctors either worked for themselves or were funded by charities or religious institutions, and many people had no access to them at all. Virus was a relatively new concept in 1918, and when the flu arrived medics were almost helpless. They had no reliable diagnostic test, no effective vaccine, no antiviral drugs and no antibiotics – which might have treated the bacterial complications of the flu that killed most of its victims, in the form of pneumonia. Public health measures – especially social distancing measures such as quarantine that we’re employing again today – could be effective, but they were often implemented too late, because flu was not a reportable disease in 1918. This meant that doctors weren’t obliged to report cases to the authorities, which in turn meant that those authorities failed to see the pandemic coming.

The lesson that health authorities took away from the 1918 catastrophe was that it was no longer reasonable to blame individuals for catching an infectious disease, nor to treat them in isolation. The 1920s saw many governments embracing the concept of socialized medicine – healthcare for all, free at the point of delivery. Russia was the first country to put in place a centralized public healthcare system, which it funded via a state-run insurance scheme, but Germany, France and the UK eventually followed suit. The U.S. took a different route, preferring employer-based insurance schemes – which began to proliferate from the 1930s on – but all of these nations took steps to consolidate healthcare, and to expand access to it, in the post-flu years.

Many countries also created or revamped health ministries in the 1920s. This was a direct result of the pandemic, during which public health leaders had been either left out of cabinet meetings entirely, or reduced to pleading for funds and powers from other departments. Countries also recognized the need to coordinate public health at the international level, since clearly, contagious diseases didn’t respect borders. 1919 saw the opening, in Vienna, Austria, of an international bureau for fighting epidemics – a forerunner, along with the health branch of the short-lived League of Nations, of today’s World Health Organization (WHO).

A hundred years on from the 1918 flu, the WHO is offering a global response to a global threat. But the WHO is underfunded by its member nations, many of which have ignored its recommendations – including the one not to close borders. COVID-19 has arrived at a time when European nations are debating whether their healthcare systems, now creaking under the strain of larger, aging populations, are still fit for purpose, and when the US is debating just how universal its system really is.

Depending on how bad this new pandemic gets, it may force a rethink in both regions. In the U.S., for example, we have already seen heated discussion of the costs and availability of COVID-19 testing, which could help revive the proposals to make healthcare more affordable, that President Obama put forward in his 2010 healthcare reform plan. In Europe, meanwhile, the outbreak could re-ignite a long-running debate over whether people should pay to use national health services (other than indirectly, through taxes or insurance schemes) – for example through a monthly membership fee. Whether current outbreak generates real change remains to be seen, but one thing is certain: we are being reminded that pandemics are a social problem, not an individual one.

Before coronavirus, Seattle was under siege by the deadliest flu in history. Here's what life was like.

Elizabeth Weise, USA TODAY•March 8, 2020SEATTLE — As the coronavirus epidemic threatens Seattle, warnings to remain inside are starting to echo the city's 1918 crisis, when the Spanish flu forced many into lockdown.

My great-aunt Violet Harris was 15 when it hit. Partly out of boredom, she began keeping a diary. Her family and friends eventually emerged unscathed, if a little stir-crazy, from the tedium of having schools closed, mandates that masks be worn outside at all times and restrictions on group events.

At least 16 people have died in Washington state because of coronavirus, with most of the fatalities occurring in the greater Seattle area. The city's major employers, including Microsoft, Amazon and Facebook, have told employees to stay home for at least three weeks. Local universities have called shifted to online classes for the rest of the quarter, including the University of Washington's 47,000 students.

More Seattle: Coronavirus fears are making shoppers 'erratic' in Washington - and businesses are already seeing sharp declines

The city faced a much different health crisis a century ago. Many people mistakenly believe that Seattle was an epicenter of the Spanish influenza epidemic of 1918, which killed as many as 50 million people as it raged around the globe. That's partly because one of the iconic photos of the global pandemic shows a line of Seattle policemen all wearing masks.

Policemen in Seattle wearing masks made by the Red Cross, during the influenza epidemic. December 1918.

That's actually the opposite of what happened, said Leonard Garfield, executive director of Seattle's Museum of History and Industry.

The epidemic had been spreading through the world in the spring of 1918 but was little reported, in part because national leaders didn't want the fear of it to affect public support for World War I.

The flu reemerged in the fall of 1918, hitting major cities like Boston, Cincinnati and Philadelphia hard. Seattle, home to about 400,000 people at the time and at the far northwest of the country, didn't begin to see cases until slightly later.

"That gave Seattle some time to prepare," said Garfield. "As they saw it coming, they acted fairly quickly. One of the first things they did was to close down large public gatherings and the schools."

Coronavirus is spreading in the US: Here's everything to know, from symptoms to how to protect yourself

At the time, my Great Aunt Vi, as our family called her, was a junior at Lincoln High School. For her, the biggest — and happiest — news of the day was that the schools were closing.

On Oct. 5. 1918, she wrote in her diary: “It was announced in the papers tonight that all churches, shows and schools would be closed until further notice, to prevent Spanish influenza from spreading. Good idea? I’ll say it is! So will every other school kid, I calculate. … The only cloud in my sky is that the (School) Board will add the missed days on to the end of the term.”

That's actually the opposite of what happened, said Leonard Garfield, executive director of Seattle's Museum of History and Industry.

The epidemic had been spreading through the world in the spring of 1918 but was little reported, in part because national leaders didn't want the fear of it to affect public support for World War I.

The flu reemerged in the fall of 1918, hitting major cities like Boston, Cincinnati and Philadelphia hard. Seattle, home to about 400,000 people at the time and at the far northwest of the country, didn't begin to see cases until slightly later.

"That gave Seattle some time to prepare," said Garfield. "As they saw it coming, they acted fairly quickly. One of the first things they did was to close down large public gatherings and the schools."

Coronavirus is spreading in the US: Here's everything to know, from symptoms to how to protect yourself

At the time, my Great Aunt Vi, as our family called her, was a junior at Lincoln High School. For her, the biggest — and happiest — news of the day was that the schools were closing.

On Oct. 5. 1918, she wrote in her diary: “It was announced in the papers tonight that all churches, shows and schools would be closed until further notice, to prevent Spanish influenza from spreading. Good idea? I’ll say it is! So will every other school kid, I calculate. … The only cloud in my sky is that the (School) Board will add the missed days on to the end of the term.”

Violet Harris, a Seattle resident who lived through the 1918 Spanish flu epidemic, in front of her house near the city's University District.

In the early 1900s, public health infrastructure was only just beginning to be developed and Seattle was a little ahead of the curve, Garfield said.

"There was a fairly progressive civic mindset in Washington state at that time. Seattle had a brand new city public health officer and there was a state public department, as well," he said.

Nonetheless, the disease began to spread. It was, as usual, a rainy October. Vi had borrowed her best friend Rena's umbrella but heard hard news from a neighbor when she went to give it back.

On Oct. 18, 1918, she wrote: “She said Rena was sick and could hardly walk. I walked on a bit further when I met Mr. B. (Rena’s father) dressed in his best. He said Mrs. B and Rena were sick. That it was the flu and I’d better not go in. I didn’t. … I’m awfully sorry about the B’s. They seem to get everything that comes along. I hope they will be up soon. .... It is too bad, but then no one can take the chance of getting the flu. It’s too dangerous. I think they ought to go to the hospital. Mr. B. can certainly not give them the proper care. I hope he doesn’t get it. Then they would be in a fix.”

Rena's family later recovered.

In the early 1900s, public health infrastructure was only just beginning to be developed and Seattle was a little ahead of the curve, Garfield said.

"There was a fairly progressive civic mindset in Washington state at that time. Seattle had a brand new city public health officer and there was a state public department, as well," he said.

Nonetheless, the disease began to spread. It was, as usual, a rainy October. Vi had borrowed her best friend Rena's umbrella but heard hard news from a neighbor when she went to give it back.

On Oct. 18, 1918, she wrote: “She said Rena was sick and could hardly walk. I walked on a bit further when I met Mr. B. (Rena’s father) dressed in his best. He said Mrs. B and Rena were sick. That it was the flu and I’d better not go in. I didn’t. … I’m awfully sorry about the B’s. They seem to get everything that comes along. I hope they will be up soon. .... It is too bad, but then no one can take the chance of getting the flu. It’s too dangerous. I think they ought to go to the hospital. Mr. B. can certainly not give them the proper care. I hope he doesn’t get it. Then they would be in a fix.”

Rena's family later recovered.

Violet Harris' drawing of what the masks everyone in Seattle was ordered to wear when outside looked like.

On October 27, 1918, Vi wrote: “Rena called me up. She is well now …. I asked her what it felt like to have the influenza, and she said, ‘Don’t get it.’”

Seattle was important economically and to the war effort because of the large concentration of shipyards and army and navy stations in the area, one reason why such drastic measures were undertaken, Garfield said.

Oct. 28, 1918: “It says in to-night’s paper that to-morrow all Seattle will be wearing masks. No one will be allowed on a streetcar without one. Gee! People will look funny — like ghosts."

There were immediate shortages of the masks. Vi's father Cornelius was sent out to buy the family of seven masks but could only find three. Violet pasted articles from the local paper about the fashions in masks in her diary.

On October 27, 1918, Vi wrote: “Rena called me up. She is well now …. I asked her what it felt like to have the influenza, and she said, ‘Don’t get it.’”

Seattle was important economically and to the war effort because of the large concentration of shipyards and army and navy stations in the area, one reason why such drastic measures were undertaken, Garfield said.

Oct. 28, 1918: “It says in to-night’s paper that to-morrow all Seattle will be wearing masks. No one will be allowed on a streetcar without one. Gee! People will look funny — like ghosts."

There were immediate shortages of the masks. Vi's father Cornelius was sent out to buy the family of seven masks but could only find three. Violet pasted articles from the local paper about the fashions in masks in her diary.

An article from the local Seattle paper about the fashions in masks due to the Spanish influenza epidemic in 1918.

Oct. 31, 1918: “I stayed in all day and didn’t even go to Rena’s. The flu seems to be spreading, and Mama doesn’t want us to go around more than we need to.”

Violet spent the next two weeks reading and sewing on a new dress for school and trying out new recipes from the paper, including one for fudge that turned out so badly she had to throw half the batch out.

Oct. 31, 1918: “I stayed in all day and didn’t even go to Rena’s. The flu seems to be spreading, and Mama doesn’t want us to go around more than we need to.”

Violet spent the next two weeks reading and sewing on a new dress for school and trying out new recipes from the paper, including one for fudge that turned out so badly she had to throw half the batch out.

An amusing story in the local Seattle paper about the requirement that everyone wear masks during the 1918 Spanish influenza epidemic there.

Finally, after almost six weeks, restrictions on public gatherings were lifted. Vi was happy to get to go out but not thrilled at going back to school.

Nov. 12, 1918: “The ban was lifted to-day. No more .... masks. Everything open too. 'The Romance of Tarzan' is on at the Coliseum (movie theater) as it was about 6 weeks ago. I’d like to see it awfully. .... School opens this week — Thursday! Did you ever? As if they couldn’t have waited till Monday!”

Finally, after almost six weeks, restrictions on public gatherings were lifted. Vi was happy to get to go out but not thrilled at going back to school.

Nov. 12, 1918: “The ban was lifted to-day. No more .... masks. Everything open too. 'The Romance of Tarzan' is on at the Coliseum (movie theater) as it was about 6 weeks ago. I’d like to see it awfully. .... School opens this week — Thursday! Did you ever? As if they couldn’t have waited till Monday!”

1918: Seattle Mayor Ole Hanson bans public assembly for more than five weeks, closing all schools, churches, synagogues and theaters to stop the spread of the Spanish flu.

Nov. 14, 1918: “Our teachers were pretty lenient to-day. Except Miss Streator (her Latin teacher.) She gave out the words just the same as if we hadn’t had 6 weeks to forget them in. I got 75.”

Violet lived until 1954, having experienced an event that quickly faded from the public's memory.

"It was called the forgotten illness," said Garfield.

Nov. 14, 1918: “Our teachers were pretty lenient to-day. Except Miss Streator (her Latin teacher.) She gave out the words just the same as if we hadn’t had 6 weeks to forget them in. I got 75.”

Violet lived until 1954, having experienced an event that quickly faded from the public's memory.

"It was called the forgotten illness," said Garfield.

Diaries of Violet Harris, who was 15 when the Spanish flu epidemic shut Seattle down in 1918.

But Seattle's quick and draconian action was important in stopping a disease that is estimated to have killed more than 1,500 people in the city and somewhere between 700,000 and 1 million people across the United States, said Garfield.

"Some people say the action we took pretty seriously slowed the spread of the infection and helped hasten the end," he said.

But Seattle's quick and draconian action was important in stopping a disease that is estimated to have killed more than 1,500 people in the city and somewhere between 700,000 and 1 million people across the United States, said Garfield.

"Some people say the action we took pretty seriously slowed the spread of the infection and helped hasten the end," he said.

No comments:

Post a Comment