It heralds a rare success in the reversal of environmental damage and shows that global action can make a difference

Louise Boyle New York THE INDEPENDENT 3/26/2020

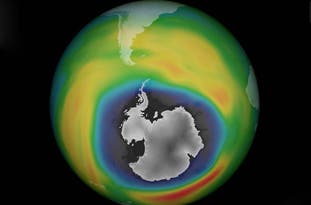

The ozone layer is continuing to heal and has the potential to fully recover, according to a new study.

A scientific paper, published in Nature, heralds a rare success in the reversal of environmental damage and shows that orchestrated global action can make a difference.

The ozone layer is a protective shield in the Earth’s stratosphere which absorbs most of the ultraviolet radiation reaching us from the sun.

Without the ozone layer it would be nearly impossible for anything to survive on the planet.

In the past, human use of substances – chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) – caused such life-threatening damage to the ozone layer that in 1987, an international treaty called the “Montreal Protocol” was adopted to ban them.

Read more

Air pollution drops in cities as UK begins coronavirus lockdown

Coronavirus: Air pollution and CO2 fall rapidly as virus spreads

Air pollution over Italy plummets as factories close and travel halted

Everyday domestic fuels to be phased out to combat air pollution

Pet dog becomes first canine in the UK to help combat air pollution

Antara Banerjee, a CIRES Visiting Fellow at the University of Colorado Boulder who also works at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), is lead author of the study.

She told The Independent: “We found signs of climate changes in the southern hemisphere, specifically in the air circulation patterns.

“The challenge was showing that these changing air circulation patterns were due to the shrinking ozone hole following the implementation of the Montreal Protocol.

“The jet stream in the southern hemisphere was gradually shifting towards the south pole in the last decades of the 20th century due to ozone depletion.

“Our study found that movement has stopped since 2000 and might even be reversing. The pause in movement began around the same time that the ozone hole started to recover.

“The emissions of ozone-depleting substances that were responsible for the ozone hole - the CFCs from spray cans and refrigerants – started to decline around 2000, thanks to the Montreal Protocol.”

She added: “It’s not just ozone that affects the jet stream – CO2 also has an effect. What we are seeing is that there is a ‘tug-of-war’ between ozone recovery, which pulls the jet stream one way (to the North), and rising CO2, which pulls the other way (to the South).

“We are seeing the pause in the shifting jet stream because these two forces are currently in balance. That might change in the future when ozone has fully recovered and CO2 carries on pushing it south.”

The impacts of this “pause” in shifting wind patterns varies, meaning parts of the world will be affected differently.

She said: “In Australia, for example, before 2000 in the ozone-depletion era, it was suggested that winters were drying because the jet stream was moving further south and taking rain-bearing storms away from that region. Those changes might now stabilise which could be good news for Australia.

“For other regions like South America, ozone-depletion had caused an expansion of the tropics and led to more rainfall. Bands of agricultural production widened which was good for them but might now stabilise. That has implications for their economies and food security.”

Overall, it is good news for the fight against climate change.

She added: “The second most important point of the study, which I would say is a very good finding, is further evidence that the ozone hole is shrinking and that is thanks to the Montreal Protocol.

“It shows that this international treaty has worked and we can reverse the damage that we’ve already done to our planet. That’s a lesson to us all that can hopefully be applied to our greenhouse gas emissions to tackle climate change.

“If we keep adhering to this protocol then the ozone hole is projected to recover – at different times, in different parts of the atmosphere. In some regions, we think it might happen in the next couple of decades and in others much later in the century.”

No comments:

Post a Comment