Throbbing Gristle

'I smeared Gen in flour paste and whipped him hard': an extract from Cosey Fanni Tutti's book

The art provocateur recalls life in an art commune in Hull, fighting the Hells Angels and thrashing Genesis P Orridge on stage in Amsterdam

Cosey Fanni Tutti

Thu 22 Feb 2018

A COUM performance outside Ferens art gallery in

Hull in 1971 (Tutti second from left). Photograph:

Courtesy: Cosey Fanni Tutti

I’d gone to an “acid test” at the union at Hull University. I walked in, paid my entrance fee and received my tab. People were already tripping when I arrived: they were on the floor groping one another or playing with a bathtub of coloured jelly. A guy was playing the saxophone, free jazz-style. The notes were so jarring, fast and scatty that it drove me crazy. As I went to leave, I saw what I thought was a hallucination: a small, beautiful guy dressed in a black graduation gown, complete with mortarboard and a wispy, pale-lilac goatee beard.

About a week later, I was out dancing when a guy came over to me and said: “Cosmosis, Genesis would like to see you.” “What?” It was explained to me that a guy called Genesis had seen me and named me Cosmosis. It was the man I thought I had hallucinated, and he wanted us to get together. “Gen was so beautiful,” reads an entry in my diary for November 1969. “His eyes were a clear blue, his hair dark brown and his skin a clear, golden colour. He smiled so beautifully.”

I started seeing Gen. I’d never met anyone like him. He was very well read, quite the archetypal revolutionary-cum-bohemian artist. He’d moved into a flat in Spring Bank, where my friend Graham also lived. Gen slept under the kitchen table, in a sleeping bag inside a polythene tunnel he called his rainshell. It was a strange and unromantic place to conduct our liaisons, but it made some sense: it was free, and warm from the cooker. My visits weren’t the hot, lusty love affair I’d come to expect from previous relationships, and there were arguments, unexpected at such an early stage. I put it down to Gen being very sensitive, and also his liberal view of relationships: that “no ties” posturing.

The Ho Ho Funhouse, which we later moved in to, was my first home away from home – a far cry from Bilton Grange housing estate. It was part of Wellington House, a Victorian building close to the fruit market on Queen Street. My room, which was small and dark, faced on to a dank alley at the back. Moses, as we called him due to the way he looked, and Gen shared a room opposite. Among all the other people living there was Roger, who had escaped from prison, taking the Midnight Express from Turkey and arriving back at the Funhouse after being severely beaten on the soles of his feet and suffering from dysentery. .

I’d gone to an “acid test” at the union at Hull University. I walked in, paid my entrance fee and received my tab. People were already tripping when I arrived: they were on the floor groping one another or playing with a bathtub of coloured jelly. A guy was playing the saxophone, free jazz-style. The notes were so jarring, fast and scatty that it drove me crazy. As I went to leave, I saw what I thought was a hallucination: a small, beautiful guy dressed in a black graduation gown, complete with mortarboard and a wispy, pale-lilac goatee beard.

About a week later, I was out dancing when a guy came over to me and said: “Cosmosis, Genesis would like to see you.” “What?” It was explained to me that a guy called Genesis had seen me and named me Cosmosis. It was the man I thought I had hallucinated, and he wanted us to get together. “Gen was so beautiful,” reads an entry in my diary for November 1969. “His eyes were a clear blue, his hair dark brown and his skin a clear, golden colour. He smiled so beautifully.”

I started seeing Gen. I’d never met anyone like him. He was very well read, quite the archetypal revolutionary-cum-bohemian artist. He’d moved into a flat in Spring Bank, where my friend Graham also lived. Gen slept under the kitchen table, in a sleeping bag inside a polythene tunnel he called his rainshell. It was a strange and unromantic place to conduct our liaisons, but it made some sense: it was free, and warm from the cooker. My visits weren’t the hot, lusty love affair I’d come to expect from previous relationships, and there were arguments, unexpected at such an early stage. I put it down to Gen being very sensitive, and also his liberal view of relationships: that “no ties” posturing.

The Ho Ho Funhouse, which we later moved in to, was my first home away from home – a far cry from Bilton Grange housing estate. It was part of Wellington House, a Victorian building close to the fruit market on Queen Street. My room, which was small and dark, faced on to a dank alley at the back. Moses, as we called him due to the way he looked, and Gen shared a room opposite. Among all the other people living there was Roger, who had escaped from prison, taking the Midnight Express from Turkey and arriving back at the Funhouse after being severely beaten on the soles of his feet and suffering from dysentery. .

Photograph: John Krivine

At first I felt a little out of my depth, being the youngest, and the only person who hadn’t gone to university. I was slightly in awe of Gen. I learned that he’d won a poetry prize while studying English at Hull University, that he and radical student friends had started Worm, a student magazine that was free from editorial control but shortlived because of its obscene and “dangerous” content. After he’d dropped out, he’d joined an artists’ commune in London, called Transmedia Explorations. Gen learned a lot from his short time with them – but he never mentioned to me the fact that much of what he presented as “his” concept for his new project, COUM Transmissions, came from Transmedia Explorations and its predecessor, the Exploding Galaxy: life as art, communal creativity, everyone is an artist, costumes, rituals, play, artworks, scavenging for art materials, street theatre, rejection of conventions, and the advocation of sexual liberation.

Gen and his friends would go on shopping trips, returning with a holdall full of books and other items “liberated” from various sources. I went shopping with Gen and a friend one day to the food hall in Hammonds (the Harrods of Hull). When we paid and went to leave, store detectives escorted us to a side room. I hadn’t taken anything, so handed my bag over without a second thought. They emptied our bags to reveal stolen food. I was gobsmacked. My attempts to explain that I hadn’t known or done anything fell on deaf ears.

We were all taken to the police station and charged with shoplifting. We were asked our address, but gave “no fixed abode”. If we’d given the Ho Ho Funhouse address, the police would have gone there and found drugs. They put us in cells for the night. After an hour, my door opened and I was taken to the front desk. I saw Mum, her eyes red from crying. She held me tight. I asked her how she knew I was there. The police had rung Dad and said: “We have your daughter. She’s been sleeping rough with two young men.”

Dad was appalled. She’d begged him to drive her to the police station, but he wouldn’t come inside. I assured her I was fine, that I wasn’t sleeping rough, or with two men. She left feeling relatively comforted. I went back to my cell and the next morning me, Gen and John were found guilty, fined £10 each (despite pleading poverty), and set free. The air had never smelled so good.

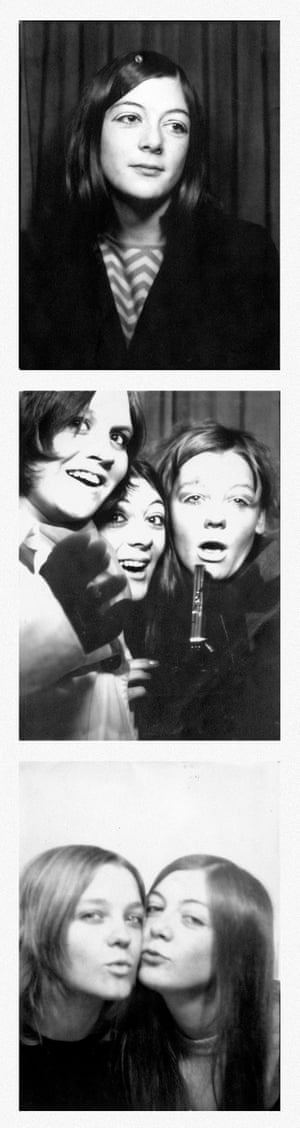

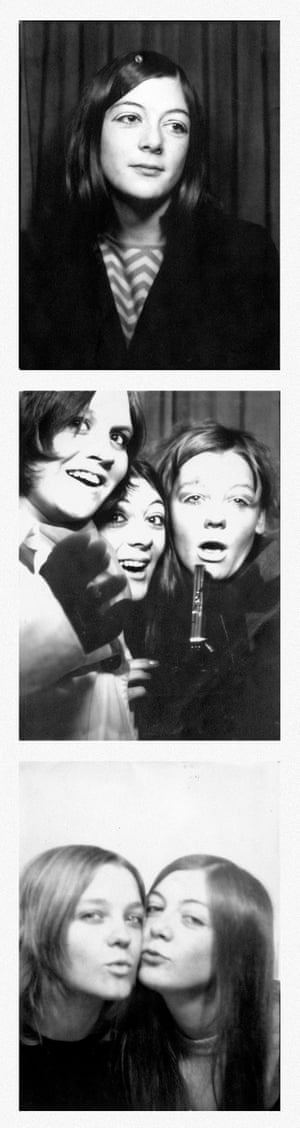

Photobooth snaps of Tutti and friends

One night at the Funhouse, we were enjoying having the building to ourselves, when we heard the roar of motorbikes, followed swiftly by a smashing sound as the Hells Angels broke in through our front door and tore through the house, spraypainting the walls and ransacking the place. For some reason, they didn’t make it as far as us on the top floor. When the noise subsided, we quietly made our way downstairs to find they’d congregated in the communal room and were giving one of their “prospects” a mouth-scrubbing with Ajax toilet cleaner.

My background meant I was more savvy at handling Hull hardcases than the others. I was confronted by one of the bikers’ girlfriends, a tough blonde girl they all called Glob. She was surprised at my combative response to her threats. I entered into a dialogue with a couple of the guys. Some of them came from Longhill Estate, near my family home. That was our saving grace. We ended up having a half-civil conversation, sparring until we arrived at an amicable kind of “understanding”, and they left.

When the other commune members returned, Bronwyn was particularly pissed off as the bikers had sprayed “Bronwyn pulls a train” in huge letters across her room. This is a term used by the Angels for women who had sex with one man after another to gain status. It wasn’t the nicest thing to come home to.

In the mid-1970s, the COUM team took a show to Amsterdam. Being a sexually liberated place, Amsterdam seemed an opportunity to indulge ourselves, and we took the brakes off. To start, Foxtrot walked on looking menacing in his SS leather coat and hat, his riding boots and sunglasses, and wielding a blowtorch, which he used to light the torches on the stage. He and I had a scene together, both dressed as homosexual soldiers, kissing and groping.

Gen had wanted me to give Foxtrot a blowjob, but I refused. Biggles was on a table being massaged by Fizzy in his “Shirley Shassey” dress and he offered Biggles the “extra” service, then turned to the audience, smiling, and proceeded to oil Biggles’ bits – rather too vigorously for comfort, judging by Biggles’ face.

Sleazy was positioned to one side of the stage, fully dressed, seated alone on a chair, softly lit, reading aloud his public-schoolboy sexual fantasies from handwritten notes. I had a much more full-on time. I strode on stage, dominatrix-style, in high heels but otherwise naked save for a strap costume that didn’t cover much. I’d made it from strips of black PVC and gold buckles I’d found in a bin.

I stood watching a naked Gen being chained to a cross. I daubed him in flour paste and chicken’s feet and whipped him hard. Gen had told me to whip him properly – it had to be real. I don’t think he’d really thought about what being whipped meant in terms of pain, or that I’d actually do it, but I really got into it, and Fizzy was itching to have a go, too. I had to hold back a bit the second night because of the welts that I’d inflicted.

We’d performed to 1,500 people each night. We’d had little sleep but felt elated at what we’d done. Whipping Gen crucified on the cross worked so well that we restaged it back in Britain for a new COUM poster image. Sleazy did some photographs with Gen drunk, cuffed and chained to the cross, and me in the foreground in my strap costume clutching the whip. Me and Sleazy loved it, but Gen wasn’t too keen. I thought it reflected a shift in the dynamics of my and Gen’s personal and working relationship. For the first time I was in the dominant position.

I was constantly having to second-guess Gen’s mood swings. Nothing I did was enough. He showed no empathy towards me – it was always about him. If I had an early start for a photo or film shoot, he’d keep me up late, talking about himself, saying he was depressed and needing reassurance. He fed off me like a parasite. I knew my life with Gen couldn’t continue.

Throbbing Gristle in the 1970s. Photograph: Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images

On 1 August 1978, as we lay in bed, I told Gen I thought that we should separate. First there were tears, from us both. I held him close. I hated making him so sad. When he realised he couldn’t talk me round, the reality hit home. “But you’re my battery – I feed off you,” he said. No mention of love. “That’s why I have to leave,” I said. “I feel like I’m being eaten away.”

He leapt on top of me and started strangling me. “If I can’t have you, nobody can!” I was strong enough to get him off me and hold him down until his temper subsided a bit. He was wild-eyed, and I suspected that as soon as I let go of him, he’d flip again. I jumped up, ran through to the front bedroom, dressed as quickly as I could, and grabbed the bag of essentials that I’d thankfully packed ages ago. I heard Gen get out of bed and turned as he came running after me. He was so fast. “All because of THAT!” he screamed at me as he kicked me so hard in my crotch that it almost lifted me off the ground. I was doubled over in pain, holding myself. I couldn’t move. Then he unleashed a torrent of punches and kicks and delivered a verbal blow that hurt me more: “I’d never have let you kill my baby if I’d known you’d leave me.” I was stunned to hear him use the termination I’d had in this way. “My baby”? Not “our baby”? How cruel to use the child I’d mourned against me.

Me and Gen living apart didn’t seem to adversely affect Throbbing Gristle, the band that evolved from COUM. We were on fire with ideas. The band took a trip to visit our friend Monte, who was now living in San Francisco. We all slept on the floor of his living room, which was difficult as Gen kept wanting to sleep with me.

Cosey Fanni Tutti: 'I don’t like acceptance. It makes me think I've done something wrong'

I took the opportunity to get an all-over tan. I hated bikini marks – they didn’t look good when I was stripping. I was on my own in the garden, lying on my front in a red G-string, half-asleep. Suddenly there was a great thud. I sprang up to see that a large cement block had landed about six inches from my head. Gen had thrown it from Monte’s balcony and was standing there staring down in silence.

He could have killed me. I shouted at him and Monte came out to see what was going on. He was horrified, but Gen carried on like nothing had happened. With hindsight, it’s unbelievable that Gen wasn’t brought to account. Maybe Monte made him realise what a narrow escape he – and I – had had. That put a halt to any more sunbathing for me when Gen was around.

• This is an edited extract from Art Sex Music by Cosey Fanni Tutti, which is published by Faber & Faber on 6 April at £14.99. Order it for £12.74 at bookshop.theguardian.com. COUM Transmissions is a series of events at Hull 2017 UK City of Culture

At first I felt a little out of my depth, being the youngest, and the only person who hadn’t gone to university. I was slightly in awe of Gen. I learned that he’d won a poetry prize while studying English at Hull University, that he and radical student friends had started Worm, a student magazine that was free from editorial control but shortlived because of its obscene and “dangerous” content. After he’d dropped out, he’d joined an artists’ commune in London, called Transmedia Explorations. Gen learned a lot from his short time with them – but he never mentioned to me the fact that much of what he presented as “his” concept for his new project, COUM Transmissions, came from Transmedia Explorations and its predecessor, the Exploding Galaxy: life as art, communal creativity, everyone is an artist, costumes, rituals, play, artworks, scavenging for art materials, street theatre, rejection of conventions, and the advocation of sexual liberation.

Gen and his friends would go on shopping trips, returning with a holdall full of books and other items “liberated” from various sources. I went shopping with Gen and a friend one day to the food hall in Hammonds (the Harrods of Hull). When we paid and went to leave, store detectives escorted us to a side room. I hadn’t taken anything, so handed my bag over without a second thought. They emptied our bags to reveal stolen food. I was gobsmacked. My attempts to explain that I hadn’t known or done anything fell on deaf ears.

We were all taken to the police station and charged with shoplifting. We were asked our address, but gave “no fixed abode”. If we’d given the Ho Ho Funhouse address, the police would have gone there and found drugs. They put us in cells for the night. After an hour, my door opened and I was taken to the front desk. I saw Mum, her eyes red from crying. She held me tight. I asked her how she knew I was there. The police had rung Dad and said: “We have your daughter. She’s been sleeping rough with two young men.”

Dad was appalled. She’d begged him to drive her to the police station, but he wouldn’t come inside. I assured her I was fine, that I wasn’t sleeping rough, or with two men. She left feeling relatively comforted. I went back to my cell and the next morning me, Gen and John were found guilty, fined £10 each (despite pleading poverty), and set free. The air had never smelled so good.

Photobooth snaps of Tutti and friends

One night at the Funhouse, we were enjoying having the building to ourselves, when we heard the roar of motorbikes, followed swiftly by a smashing sound as the Hells Angels broke in through our front door and tore through the house, spraypainting the walls and ransacking the place. For some reason, they didn’t make it as far as us on the top floor. When the noise subsided, we quietly made our way downstairs to find they’d congregated in the communal room and were giving one of their “prospects” a mouth-scrubbing with Ajax toilet cleaner.

My background meant I was more savvy at handling Hull hardcases than the others. I was confronted by one of the bikers’ girlfriends, a tough blonde girl they all called Glob. She was surprised at my combative response to her threats. I entered into a dialogue with a couple of the guys. Some of them came from Longhill Estate, near my family home. That was our saving grace. We ended up having a half-civil conversation, sparring until we arrived at an amicable kind of “understanding”, and they left.

When the other commune members returned, Bronwyn was particularly pissed off as the bikers had sprayed “Bronwyn pulls a train” in huge letters across her room. This is a term used by the Angels for women who had sex with one man after another to gain status. It wasn’t the nicest thing to come home to.

In the mid-1970s, the COUM team took a show to Amsterdam. Being a sexually liberated place, Amsterdam seemed an opportunity to indulge ourselves, and we took the brakes off. To start, Foxtrot walked on looking menacing in his SS leather coat and hat, his riding boots and sunglasses, and wielding a blowtorch, which he used to light the torches on the stage. He and I had a scene together, both dressed as homosexual soldiers, kissing and groping.

Gen had wanted me to give Foxtrot a blowjob, but I refused. Biggles was on a table being massaged by Fizzy in his “Shirley Shassey” dress and he offered Biggles the “extra” service, then turned to the audience, smiling, and proceeded to oil Biggles’ bits – rather too vigorously for comfort, judging by Biggles’ face.

Sleazy was positioned to one side of the stage, fully dressed, seated alone on a chair, softly lit, reading aloud his public-schoolboy sexual fantasies from handwritten notes. I had a much more full-on time. I strode on stage, dominatrix-style, in high heels but otherwise naked save for a strap costume that didn’t cover much. I’d made it from strips of black PVC and gold buckles I’d found in a bin.

I stood watching a naked Gen being chained to a cross. I daubed him in flour paste and chicken’s feet and whipped him hard. Gen had told me to whip him properly – it had to be real. I don’t think he’d really thought about what being whipped meant in terms of pain, or that I’d actually do it, but I really got into it, and Fizzy was itching to have a go, too. I had to hold back a bit the second night because of the welts that I’d inflicted.

We’d performed to 1,500 people each night. We’d had little sleep but felt elated at what we’d done. Whipping Gen crucified on the cross worked so well that we restaged it back in Britain for a new COUM poster image. Sleazy did some photographs with Gen drunk, cuffed and chained to the cross, and me in the foreground in my strap costume clutching the whip. Me and Sleazy loved it, but Gen wasn’t too keen. I thought it reflected a shift in the dynamics of my and Gen’s personal and working relationship. For the first time I was in the dominant position.

I was constantly having to second-guess Gen’s mood swings. Nothing I did was enough. He showed no empathy towards me – it was always about him. If I had an early start for a photo or film shoot, he’d keep me up late, talking about himself, saying he was depressed and needing reassurance. He fed off me like a parasite. I knew my life with Gen couldn’t continue.

Throbbing Gristle in the 1970s. Photograph: Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images

On 1 August 1978, as we lay in bed, I told Gen I thought that we should separate. First there were tears, from us both. I held him close. I hated making him so sad. When he realised he couldn’t talk me round, the reality hit home. “But you’re my battery – I feed off you,” he said. No mention of love. “That’s why I have to leave,” I said. “I feel like I’m being eaten away.”

He leapt on top of me and started strangling me. “If I can’t have you, nobody can!” I was strong enough to get him off me and hold him down until his temper subsided a bit. He was wild-eyed, and I suspected that as soon as I let go of him, he’d flip again. I jumped up, ran through to the front bedroom, dressed as quickly as I could, and grabbed the bag of essentials that I’d thankfully packed ages ago. I heard Gen get out of bed and turned as he came running after me. He was so fast. “All because of THAT!” he screamed at me as he kicked me so hard in my crotch that it almost lifted me off the ground. I was doubled over in pain, holding myself. I couldn’t move. Then he unleashed a torrent of punches and kicks and delivered a verbal blow that hurt me more: “I’d never have let you kill my baby if I’d known you’d leave me.” I was stunned to hear him use the termination I’d had in this way. “My baby”? Not “our baby”? How cruel to use the child I’d mourned against me.

Me and Gen living apart didn’t seem to adversely affect Throbbing Gristle, the band that evolved from COUM. We were on fire with ideas. The band took a trip to visit our friend Monte, who was now living in San Francisco. We all slept on the floor of his living room, which was difficult as Gen kept wanting to sleep with me.

Cosey Fanni Tutti: 'I don’t like acceptance. It makes me think I've done something wrong'

I took the opportunity to get an all-over tan. I hated bikini marks – they didn’t look good when I was stripping. I was on my own in the garden, lying on my front in a red G-string, half-asleep. Suddenly there was a great thud. I sprang up to see that a large cement block had landed about six inches from my head. Gen had thrown it from Monte’s balcony and was standing there staring down in silence.

He could have killed me. I shouted at him and Monte came out to see what was going on. He was horrified, but Gen carried on like nothing had happened. With hindsight, it’s unbelievable that Gen wasn’t brought to account. Maybe Monte made him realise what a narrow escape he – and I – had had. That put a halt to any more sunbathing for me when Gen was around.

• This is an edited extract from Art Sex Music by Cosey Fanni Tutti, which is published by Faber & Faber on 6 April at £14.99. Order it for £12.74 at bookshop.theguardian.com. COUM Transmissions is a series of events at Hull 2017 UK City of Culture

Interview

Cosey Fanni Tutti: 'I don’t like acceptance. It makes me think I've done something wrong'

Alexis Petridis

As a member of COUM and Throbbing Gristle, Cosey Fanni Tutti made art that was so shocking, the police ran them out of Hull. But now they’re being invited back – and celebrated in galleries. Here she talks about how they survived

Tue 14 Mar 2017 modified on Thu 22 Feb 2018

As a member of COUM and Throbbing Gristle, Cosey Fanni Tutti made art that was so shocking, the police ran them out of Hull. But now they’re being invited back – and celebrated in galleries. Here she talks about how they survived

Tue 14 Mar 2017 modified on Thu 22 Feb 2018

‘COUM were never confrontational. People might think we were, but we weren’t. We were just sharing something, if you like’ … Cosey Fanni Tutti. Photograph: Linda Nylind/The Guardian

There’s no getting around the fact that meeting Cosey Fanni Tutti after you’ve read her autobiography is a slightly disconcerting experience. It’s not just that she’s so nice, in a way that’s entirely at odds with the fearsome reputation of notorious 70s performance art collective COUM and Throbbing Gristle, the groundbreaking, wildly influential band COUM begat – although she certainly is.

At 65, there’s a certain formidable doesn’t-suffer-fools air about her. Even so, it’s hard to square the woman in whose kitchen I’m eating biscuits and drinking tea with the person who did the more shocking stuff described in Art Sex Music: performances so transgressive that other transgressive performance artists tended to walk out in disgust (“We ended up locked together, lying in piss, blood and vomit,” ends one characteristic description); exhibitions involving used tampons and blood-smeared dildos that caused one fulminating Tory MP to dub Tutti and the rest of COUM “wreckers of civilisation”; game plunges into the world of porn modelling and stripping as part of her art practice; music that screamed about serial killers and death camps and frequently caused uncomprehending audiences to erupt in rage and horror.

It’s more that she seems so normal, so unscathed by the extraordinary life depicted in the book. There are moments of deadpan humour in it – not least when her then-teenage son Nick comes face-to-face with some of her old work during an exhibition at the ICA (whatever parenting problems you may have encountered, it seems doubtful that you’ve ever had to, as Tutti puts it, “explain to Nick a film in which I castrated his dad”) – but it is an often harrowing read, pockmarked by familial dysfunction and violence. Between the art actions, the Throbbing Gristle gigs at which audiences tried to attack the band, the striptease bookings in dubious pubs and her turbulent, abusive relationship with COUM founder and Throbbing Gristle frontman Genesis P-Orridge, it’s hard not to be struck by how much physical danger she regularly found herself in. She looks a bit surprised when I mention it. “I didn’t think of it in the way you say it,” she shrugs. “It’s funny, isn’t it, when someone outside points it out?”

She says she’s not sure where her non-conformist streak came from, although it was there from the start, when she was still Christine Newby, the daughter of a fireman and a wages clerk from Hull’s Bilton Grange council estate. Her home life was strained: her father was emotionally distant, domineering and frequently violent; moreover he refused point-blank to let her go to art school. “That little thing I can thank him for,” she nods, “because it meant that I had to go out there and do it, not be taught it, which was brilliant. My imagination was free.”

There’s no getting around the fact that meeting Cosey Fanni Tutti after you’ve read her autobiography is a slightly disconcerting experience. It’s not just that she’s so nice, in a way that’s entirely at odds with the fearsome reputation of notorious 70s performance art collective COUM and Throbbing Gristle, the groundbreaking, wildly influential band COUM begat – although she certainly is.

At 65, there’s a certain formidable doesn’t-suffer-fools air about her. Even so, it’s hard to square the woman in whose kitchen I’m eating biscuits and drinking tea with the person who did the more shocking stuff described in Art Sex Music: performances so transgressive that other transgressive performance artists tended to walk out in disgust (“We ended up locked together, lying in piss, blood and vomit,” ends one characteristic description); exhibitions involving used tampons and blood-smeared dildos that caused one fulminating Tory MP to dub Tutti and the rest of COUM “wreckers of civilisation”; game plunges into the world of porn modelling and stripping as part of her art practice; music that screamed about serial killers and death camps and frequently caused uncomprehending audiences to erupt in rage and horror.

It’s more that she seems so normal, so unscathed by the extraordinary life depicted in the book. There are moments of deadpan humour in it – not least when her then-teenage son Nick comes face-to-face with some of her old work during an exhibition at the ICA (whatever parenting problems you may have encountered, it seems doubtful that you’ve ever had to, as Tutti puts it, “explain to Nick a film in which I castrated his dad”) – but it is an often harrowing read, pockmarked by familial dysfunction and violence. Between the art actions, the Throbbing Gristle gigs at which audiences tried to attack the band, the striptease bookings in dubious pubs and her turbulent, abusive relationship with COUM founder and Throbbing Gristle frontman Genesis P-Orridge, it’s hard not to be struck by how much physical danger she regularly found herself in. She looks a bit surprised when I mention it. “I didn’t think of it in the way you say it,” she shrugs. “It’s funny, isn’t it, when someone outside points it out?”

She says she’s not sure where her non-conformist streak came from, although it was there from the start, when she was still Christine Newby, the daughter of a fireman and a wages clerk from Hull’s Bilton Grange council estate. Her home life was strained: her father was emotionally distant, domineering and frequently violent; moreover he refused point-blank to let her go to art school. “That little thing I can thank him for,” she nods, “because it meant that I had to go out there and do it, not be taught it, which was brilliant. My imagination was free.”

Tutti with Throbbing Gristle in the 1970s

She immersed herself in Hull’s late-60s counterculture. It was at an LSD-fuelled happening in Hull University student union that she first met Genesis P-Orridge, who announced that he had rechristened her Cosmosis and that they should be together. Within weeks, she’d been thrown out of home by her father, was living with P-Orridge in a commune and was an active member of COUM. In many ways, she says, it was a liberating social and artistic experiment: “Just working with what presented itself, you know, going to jumble sales and finding these fantastic hoards, bringing it home and creating a small art work in the house, or costumes that would suggest something we could do, all ad hoc, based on chance, the way I still like it.”

But it’s hard not to notice that, despite the supposedly liberated lifestyle of the commune, it still fell to Tutti, the most prominent female member, to do all the cleaning, cooking and washing. “Another member of COUM, Spydeee, said to me recently, ‘People don’t realise how rife sexism was then, the misogyny there was even among liberal people’,” she says. “I was doing everything. Not that I didn’t see anything wrong with the role, it’s just that I was surviving. I had no home, no family to go back to, so I had to make my home as near as dammit to what was comfortable to me, and if that meant cooking, cleaning … I saw a photo from back then recently and thought, ‘What’s that around my neck?’ It was a police whistle that somebody had given me because I was always making sure that everybody did what they were supposed to do. Someone had to organise at some point.”

Initially, COUM’s art was funny and playful. There is footage of them, covered in tinsel, performing actions on the streets of Hull to crowds of apparently entranced children; they formed a band in which “everybody got on stage and did what they wanted, which was absolute chaos”, entering talent competitions and chanting “off, off” to pre-empt the inevitable audience reaction.

But gradually, their tone changed. By the mid-70s, their performances often involved nudity, live sex acts and bodily fluids: crowds of entranced children were noticeable by their absence. Tutti thinks her increasing fascination with and involvement in the world of pornography had something to do with it. She’d been including images from porn magazines in collages, she says. “I just thought: ‘It’s a bit rotten using them like this.’ I’d sooner get in there and do it myself, so I know the background behind it and how it’s made. And then, once you enter that world, things do change, they get less playful.”

Encouraged by P-Orridge, she began modelling for top-shelf magazines, then appearing in both hardcore and softcore films, and stripping. The 70s porn industry sounds pretty grim, but she says she thinks it might be worse today. “Back then, there was an unwritten code, that you treated the girls as good as you could. Nowadays … I think I expected it would be different, because of feminism for a start, and because now there are female porn sites; it seems quite liberated. But I watched that documentary about [latterday porn star] Annabel Chong that came out about 15 years ago, and it really shocked me. It might have been bad in the 70s, underground and a bit seedy, but it wasn’t violent in that way, it wasn’t treating you like a piece of meat, literally.”

‘We were playing with ideas all the time’ …

Cosey Fanni Tutti. Photograph: Linda Nylind/The Guardian

She included framed centrefolds from the magazines in COUM’s 1976 retrospective show, Prostitution. When it opened, the tabloids went berserk – as a result of the coverage, Tutti’s mother never spoke to her again – questions were asked in the House of Commons and the ICA’s public funding was threatened. In her telling of it, Tutti and the rest of COUM were genuinely hurt and bewildered by the furore: “COUM were never confrontational,” she shrugs. “People might think we were, but we weren’t, we were just … sharing something, if you like.”

Oh, come off it. It was an exhibition full of used tampons and photos from porn mags. You must have realised it was a provocative thing to do? “No. Strange isn’t it? That’s the bubble, I suppose. It was what we did every day in the studio, it was just part of my daily life, my routine: saving my Tampax for it, trying to stop the dog from eating them.” She laughs. “She was terrible for that.”

The opening of Prostitution marked the launch of Throbbing Gristle, the band formed when Tutti, P-Orridge and fellow COUM member Peter Christopherson met electronics wizard Chris Carter. If the musical results were no closer to traditional rock and pop than COUM’s free-for-all experiments, they now had a new potency and focus: the churning, terrifying noise they created gradually attracted an ever-increasing group of intense devotees, much to the band’s apparent horror. “We wore uniforms because we were playing with ideas all the time, investigating that concept of how uniformity sells a product, that was fascinating to us,” says Tutti. “That started out as an interest and then it actually worked: eventually, we played the Lyceum in London and the whole audience was wearing military uniforms. No, no, no, no: we don’t want followers.”

For all the talk of investigating concepts, Art Sex Music makes their sound seem less like an artistic exercise than an expression of the chaos in their personal lives: Tutti and Carter fell in love, which caused her relationship with P-Orridge, always fraught, to collapse in acrimony: at one juncture, he threw a breeze block at her from a balcony, narrowly missing her head. It seems a miracle the band managed to achieve anything, let alone a series of albums that spawned an entire musical genre named after their record label, Industrial: “Well, it was a struggle, it really was. I don’t know how it held together.”

Throbbing Gristle finally split up in 1981. (An attempt to regroup in the 00s was an acclaimed artistic triumph but, by all accounts, as much of a psychological nightmare as the old days.) Tutti and Carter continued to work together, as Chris and Cosey, CTI and Carter Tutti. And after almost a decade’s absence, Tutti made a triumphant return to the art world in the mid-90s.

In the interim, something deeply improbable had happened. Her work had gone from reviled to revered. In recent years, her art has been widely exhibited, bought by the Tate and the subject of a day-long festival at the ICA. Throbbing Gristle are routinely hailed as one of the most important bands of their era, while – initially unbeknownst to the pair – the music she and Carter made turned out to be a huge influence on subsequent electronic music: shows they played revisiting old material and their “cross-generational” collaboration with Nik Void of Factory Floor were rapturously received.

Most recently, nearly 45 years after COUM were effectively run out of Hull by the police, they were invited back: an exhibition of their work and a series of events based on it form a major part of the programme for Hull’s year as UK City of Culture. When I mention that she seems to have become accepted, Tutti frowns and says “I know,” in the way you might say “I know” if someone pointed out you’d just stepped in something disgusting. You’re not keen on the idea?

“I look at it like it’s retrospective acceptance, so what I feel about the work when it was done is still there, it still has meaning for me. Of its time, it was unacceptable. I don’t like acceptance, I distrust it completely, I think I’ve done something wrong, like I’ve gone off on a bad tangent and need to get back on track.” She pauses. “I mean, I understand why certain things have found their place in history, so I can accept that. But I don’t see it as acceptance of what I did then, because it wasn’t. It’s still loaded with that unacceptance.”

• Art Sex Music by Cosey Fanni Tutti is published by Faber & Faber on 6 April at £14.99. Order it for £12.74 at bookshop.theguardian.com. COUM Transmissions is a series of events at Hull 2017 UK City of Culture

She included framed centrefolds from the magazines in COUM’s 1976 retrospective show, Prostitution. When it opened, the tabloids went berserk – as a result of the coverage, Tutti’s mother never spoke to her again – questions were asked in the House of Commons and the ICA’s public funding was threatened. In her telling of it, Tutti and the rest of COUM were genuinely hurt and bewildered by the furore: “COUM were never confrontational,” she shrugs. “People might think we were, but we weren’t, we were just … sharing something, if you like.”

Oh, come off it. It was an exhibition full of used tampons and photos from porn mags. You must have realised it was a provocative thing to do? “No. Strange isn’t it? That’s the bubble, I suppose. It was what we did every day in the studio, it was just part of my daily life, my routine: saving my Tampax for it, trying to stop the dog from eating them.” She laughs. “She was terrible for that.”

The opening of Prostitution marked the launch of Throbbing Gristle, the band formed when Tutti, P-Orridge and fellow COUM member Peter Christopherson met electronics wizard Chris Carter. If the musical results were no closer to traditional rock and pop than COUM’s free-for-all experiments, they now had a new potency and focus: the churning, terrifying noise they created gradually attracted an ever-increasing group of intense devotees, much to the band’s apparent horror. “We wore uniforms because we were playing with ideas all the time, investigating that concept of how uniformity sells a product, that was fascinating to us,” says Tutti. “That started out as an interest and then it actually worked: eventually, we played the Lyceum in London and the whole audience was wearing military uniforms. No, no, no, no: we don’t want followers.”

For all the talk of investigating concepts, Art Sex Music makes their sound seem less like an artistic exercise than an expression of the chaos in their personal lives: Tutti and Carter fell in love, which caused her relationship with P-Orridge, always fraught, to collapse in acrimony: at one juncture, he threw a breeze block at her from a balcony, narrowly missing her head. It seems a miracle the band managed to achieve anything, let alone a series of albums that spawned an entire musical genre named after their record label, Industrial: “Well, it was a struggle, it really was. I don’t know how it held together.”

Throbbing Gristle finally split up in 1981. (An attempt to regroup in the 00s was an acclaimed artistic triumph but, by all accounts, as much of a psychological nightmare as the old days.) Tutti and Carter continued to work together, as Chris and Cosey, CTI and Carter Tutti. And after almost a decade’s absence, Tutti made a triumphant return to the art world in the mid-90s.

In the interim, something deeply improbable had happened. Her work had gone from reviled to revered. In recent years, her art has been widely exhibited, bought by the Tate and the subject of a day-long festival at the ICA. Throbbing Gristle are routinely hailed as one of the most important bands of their era, while – initially unbeknownst to the pair – the music she and Carter made turned out to be a huge influence on subsequent electronic music: shows they played revisiting old material and their “cross-generational” collaboration with Nik Void of Factory Floor were rapturously received.

Most recently, nearly 45 years after COUM were effectively run out of Hull by the police, they were invited back: an exhibition of their work and a series of events based on it form a major part of the programme for Hull’s year as UK City of Culture. When I mention that she seems to have become accepted, Tutti frowns and says “I know,” in the way you might say “I know” if someone pointed out you’d just stepped in something disgusting. You’re not keen on the idea?

“I look at it like it’s retrospective acceptance, so what I feel about the work when it was done is still there, it still has meaning for me. Of its time, it was unacceptable. I don’t like acceptance, I distrust it completely, I think I’ve done something wrong, like I’ve gone off on a bad tangent and need to get back on track.” She pauses. “I mean, I understand why certain things have found their place in history, so I can accept that. But I don’t see it as acceptance of what I did then, because it wasn’t. It’s still loaded with that unacceptance.”

• Art Sex Music by Cosey Fanni Tutti is published by Faber & Faber on 6 April at £14.99. Order it for £12.74 at bookshop.theguardian.com. COUM Transmissions is a series of events at Hull 2017 UK City of Culture

No comments:

Post a Comment