British Library releases vast trove of digitised 19th-century newspapers to bring stories of fugitives to life

A 1780 engraving of an Englishman selling his mistress into slavery in Barbados. Photograph: The Granger Collection/Alamy

Vanessa Thorpe

Vanessa Thorpe

THE OBSERVER

Sun 18 Jul 2021

Little is yet known of Bussa, the man behind the largest slave revolt on Barbados in 1816, but information about his life before this uprising could well lie in the columns of contemporary island newspapers. So too may further clues about what happened to Benebah, a pregnant black woman who stood up to a police officer on the island in 1834, after slavery had officially been abolished.

The missing history of these two rebels, along with many other enslaved peoples’ stories, are hiding in plain sight in vast, freshly digitised newspaper records from the island. And now the British Library is to lend its scholastic firepower and invite online volunteers to help to uncover it.

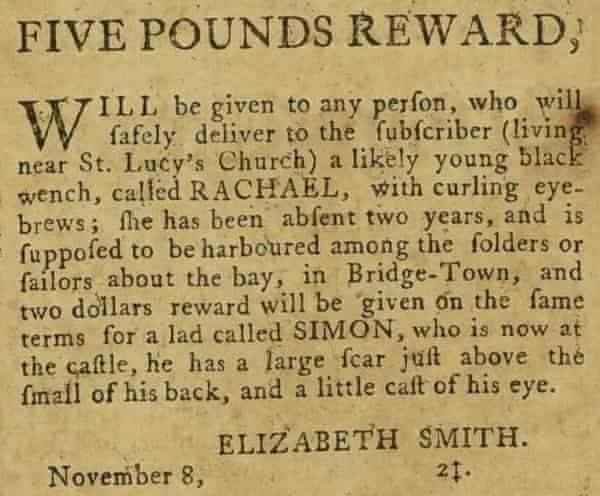

Such evidence would paint a valuable picture of the otherwise anonymous world of commercial slavery during British colonial rule. For, while much of the paperwork surrounding the trade did not use names, if someone rebelled, or attempted escape, their identity and description often appeared in a paid advertisement.

Advertisement

“These fugitive adverts, while created by enslavers, were born out of acts of resistance by those who were enslaved,” said Graham Jevon of the British Library.

“The casual normalisation of these adverts can be hard to read but each represents an individual resisting oppression – and in some cases is the only real recognition that a person existed, and almost certainly the only record of a person’s appearance, personality, and connections.”

Agents of Enslavement, a collaboration between the Barbados Department of Archives and the British Library, launches on Tuesday, making thousands of pages available to researchers and amateur historians to create a new resource for people in Barbados and Britain to find out about their ancestors.

The newspapers themselves remain in Barbados but have been digitised using a grant from the Endangered Archives Programme (EAP). The surviving pages were in an “exceptionally vulnerable” condition, said Jevon, due to their age and the tropical climate.

“The crowdsourcing will unlock some of the secrets hidden within these newspapers. While the digital copies are now freely available to view on the EAP website, the information can only be found by a close reading of every page. We need people to help us do this,” said Jevon, who will personally be looking out for one rebel name above others.

“Historical records of Bussa are scant. Exactly who he was and whether he did actually lead the rebellion has been a matter of some debate. I don’t expect to find evidence of his lead role in the rebellion but I will be particularly keen to keep an eye out for any pre-1816 references to the name Bussa.”

Advertisement

Jevon will also be scanning for mentions of Benebah, whose story he came across by chance. “While glancing through the newspapers, I stumbled across an article which described a near-fatal incident between a police officer and a pregnant black woman named Benebah,” he said.

Sun 18 Jul 2021

Little is yet known of Bussa, the man behind the largest slave revolt on Barbados in 1816, but information about his life before this uprising could well lie in the columns of contemporary island newspapers. So too may further clues about what happened to Benebah, a pregnant black woman who stood up to a police officer on the island in 1834, after slavery had officially been abolished.

The missing history of these two rebels, along with many other enslaved peoples’ stories, are hiding in plain sight in vast, freshly digitised newspaper records from the island. And now the British Library is to lend its scholastic firepower and invite online volunteers to help to uncover it.

Such evidence would paint a valuable picture of the otherwise anonymous world of commercial slavery during British colonial rule. For, while much of the paperwork surrounding the trade did not use names, if someone rebelled, or attempted escape, their identity and description often appeared in a paid advertisement.

Advertisement

“These fugitive adverts, while created by enslavers, were born out of acts of resistance by those who were enslaved,” said Graham Jevon of the British Library.

“The casual normalisation of these adverts can be hard to read but each represents an individual resisting oppression – and in some cases is the only real recognition that a person existed, and almost certainly the only record of a person’s appearance, personality, and connections.”

Agents of Enslavement, a collaboration between the Barbados Department of Archives and the British Library, launches on Tuesday, making thousands of pages available to researchers and amateur historians to create a new resource for people in Barbados and Britain to find out about their ancestors.

The newspapers themselves remain in Barbados but have been digitised using a grant from the Endangered Archives Programme (EAP). The surviving pages were in an “exceptionally vulnerable” condition, said Jevon, due to their age and the tropical climate.

“The crowdsourcing will unlock some of the secrets hidden within these newspapers. While the digital copies are now freely available to view on the EAP website, the information can only be found by a close reading of every page. We need people to help us do this,” said Jevon, who will personally be looking out for one rebel name above others.

“Historical records of Bussa are scant. Exactly who he was and whether he did actually lead the rebellion has been a matter of some debate. I don’t expect to find evidence of his lead role in the rebellion but I will be particularly keen to keep an eye out for any pre-1816 references to the name Bussa.”

Advertisement

Jevon will also be scanning for mentions of Benebah, whose story he came across by chance. “While glancing through the newspapers, I stumbled across an article which described a near-fatal incident between a police officer and a pregnant black woman named Benebah,” he said.

One of the Barbados newspaper advertisements seeking runaway slaves. Photograph: Graham Jevon/Barbados Archives / Endangered Archives Programme

Although slavery had been abolished, Benebah was still held in the transitional “apprenticeship” system and, according to a report in the Globe, stood her ground when Thomas Green, a police officer, took a loose goat from the market.

When the goat was claimed by Benebah, he refused to return it unless she paid him. During an abusive confrontation later in the market the officer became violent.

“He grabbed Benebah, intent on dragging her to the police station,” Jevon said. “She resisted; clenched her teeth on his hand. Green responded, pulled her towards him, and forced his knee into her abdomen. Benebah threw the officer to the floor, before others joined the scuffle and the officer was retrieved by two colleagues.”

Green was sent to prison by a magistrate but was then swiftly released on the basis of a certificate from a Dr Cleare stating that “the woman [was] in no immediate danger”.

“This provides a snapshot into the life of a young woman who would otherwise be forgotten by history,” said Jevon. “It is an example of the way that these newspapers can be used to start to identify people and then to trace their stories.”

The adverts were mostly posted by English owners, and the project hopes to expose any patterns behind the escape attempts. Were enslaved people more likely to run away from absentee enslavers based in Britain or from enslavers living in Barbados? But the main aim is to identify more enslaved people and their individual acts of resistance. “Unlike ‘for sale’ adverts, in which enslaved people are anonymised, the fugitive adverts required detailed descriptions to achieve their objective of recapturing people,” said Jevon. “These adverts therefore contain names, ages, detailed physical descriptions and often the names and locations of a fugitive’s family and friends.”

Although slavery had been abolished, Benebah was still held in the transitional “apprenticeship” system and, according to a report in the Globe, stood her ground when Thomas Green, a police officer, took a loose goat from the market.

When the goat was claimed by Benebah, he refused to return it unless she paid him. During an abusive confrontation later in the market the officer became violent.

“He grabbed Benebah, intent on dragging her to the police station,” Jevon said. “She resisted; clenched her teeth on his hand. Green responded, pulled her towards him, and forced his knee into her abdomen. Benebah threw the officer to the floor, before others joined the scuffle and the officer was retrieved by two colleagues.”

Green was sent to prison by a magistrate but was then swiftly released on the basis of a certificate from a Dr Cleare stating that “the woman [was] in no immediate danger”.

“This provides a snapshot into the life of a young woman who would otherwise be forgotten by history,” said Jevon. “It is an example of the way that these newspapers can be used to start to identify people and then to trace their stories.”

The adverts were mostly posted by English owners, and the project hopes to expose any patterns behind the escape attempts. Were enslaved people more likely to run away from absentee enslavers based in Britain or from enslavers living in Barbados? But the main aim is to identify more enslaved people and their individual acts of resistance. “Unlike ‘for sale’ adverts, in which enslaved people are anonymised, the fugitive adverts required detailed descriptions to achieve their objective of recapturing people,” said Jevon. “These adverts therefore contain names, ages, detailed physical descriptions and often the names and locations of a fugitive’s family and friends.”

A community workshop with the Barbados newspapers. Photograph: Barbados Archives / Endangered Archives Programme

The history of the period is obscured by the custom of giving enslaved people their enslavers’ names, but it can also make things clearer. Benebah was a common name in Barbados, with no set spelling. But the Benebah of interest to Jevon can be recognised because the newspaper article mentions she was apprenticed by John Piggot Maynard. “I was able to trace Benebah’s initial registration as a 13-year-old in 1817 to her final registration in 1834 when, aged 30, she was gifted to John Maynard’s seven-year-old daughter by a man named Richard Grannum,” he said.

Those enslaved in Barbados were predominantly black and descended from Africans, although early in the colonisation period there were also white indentured servants. Some native Americans were also enslaved. By the 19th century, most were born in Barbados, rather than Africa, and so the white community in Barbados was not as widely opposed to the 1807 act to abolish the slave trade as others were. Barbados no longer needed to import labour.

All the same, after an 1823 revolt in Demerara, the Barbadian launched a strong editorial attack on the abolitionist African Institution and its leading figures, including William Wilberforce. It blamed them for disorder and called them “a junta of fanatics … specious friends of humanity, who have not one spark of Christian feeling for the millions of human beings of their own colour”.

The history of the period is obscured by the custom of giving enslaved people their enslavers’ names, but it can also make things clearer. Benebah was a common name in Barbados, with no set spelling. But the Benebah of interest to Jevon can be recognised because the newspaper article mentions she was apprenticed by John Piggot Maynard. “I was able to trace Benebah’s initial registration as a 13-year-old in 1817 to her final registration in 1834 when, aged 30, she was gifted to John Maynard’s seven-year-old daughter by a man named Richard Grannum,” he said.

Those enslaved in Barbados were predominantly black and descended from Africans, although early in the colonisation period there were also white indentured servants. Some native Americans were also enslaved. By the 19th century, most were born in Barbados, rather than Africa, and so the white community in Barbados was not as widely opposed to the 1807 act to abolish the slave trade as others were. Barbados no longer needed to import labour.

All the same, after an 1823 revolt in Demerara, the Barbadian launched a strong editorial attack on the abolitionist African Institution and its leading figures, including William Wilberforce. It blamed them for disorder and called them “a junta of fanatics … specious friends of humanity, who have not one spark of Christian feeling for the millions of human beings of their own colour”.

No comments:

Post a Comment