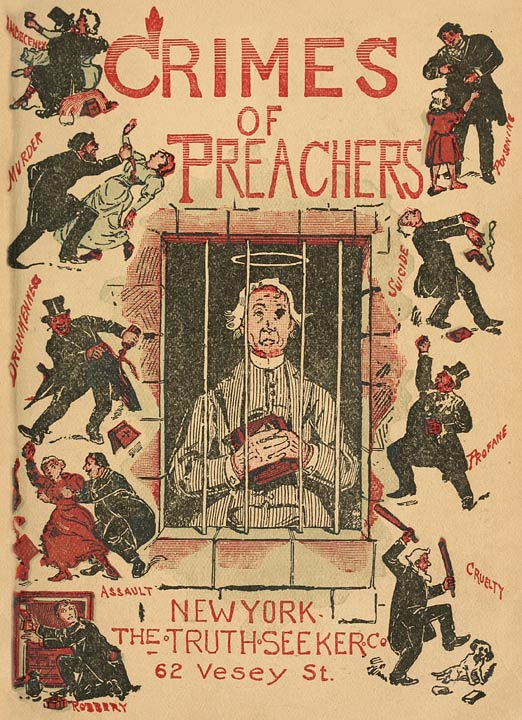

In the year 1906 the Young Men’s Christian Association of Pittsburgh, in Pennsylvania, rejected the application of an actor for membership on the ground that one of his profession could not be a moral person. Viewing the action as a slur cast on the whole theatrical profession, Mr. Henry E. Dixey, the well-known actor, offered to give one thousand dollars to charity if it could be shown that actors, man for man, were not as good as ministers of the gospel. No champion of the cloth appearing to claim Mr. Dixey’s money on that proposition, he went further and offered another thousand dollars if there could not be found a minister in jail for every state in the Union. This second challenge was likewise ignored by the clergy and the association which had provoked it, but Mr. Dixey made a few inquiries as to the proportion of ministers to actors among convicts. His research, which was far short of being thorough, discovered 43 ministers and 19 actors in jail. The investigation, so far as the ministers were concerned, could have touched only the fringe of the matter, for in eight months of the year 1914 the publishers of this work counted more than seventy reported offenses of preachers for which they were or deserved to be imprisoned, and of course the count included only those cases reported in newspapers that reached the office through an agency which scans only the more important ones. There had been nothing like a systematic reading of the press of the [6]country for these cases. Judged by 1914, the clerical convicts in 1906 must have far exceeded the number developed by Mr. Dixey’s census.

The foregoing incident is introduced here to explain the nature of this work, “Crimes of Preachers,” which, like Mr. Dixey’s challenge to the clergy in behalf of his profession, is the reply we have to make to the preachers in behalf of the unbelievers in their religion.The clergy assume to be the teachers and guardians of morality, and assert not only that belief in their astonishing creeds is necessary to an upright life, but, by implication, that a profession of faith is in a sense a guarantee of morality. It has become traditional with them to assume that the non-Christian man is an immoral man; that the sincere believer is the exemplar of the higher life, while the “Infidel,” the unbeliever, illustrates the opposite; and that whatever of morality the civilized world enjoys today it owes to the profession and practice of Christianity

No comments:

Post a Comment