From the third to fifth centuries, the psychotropic drug wu shi san or ‘five stone powder’ was a popular for its ability to open ‘the spirit and mind’

Wee Kek Koon Published: 9 Apr, 2020

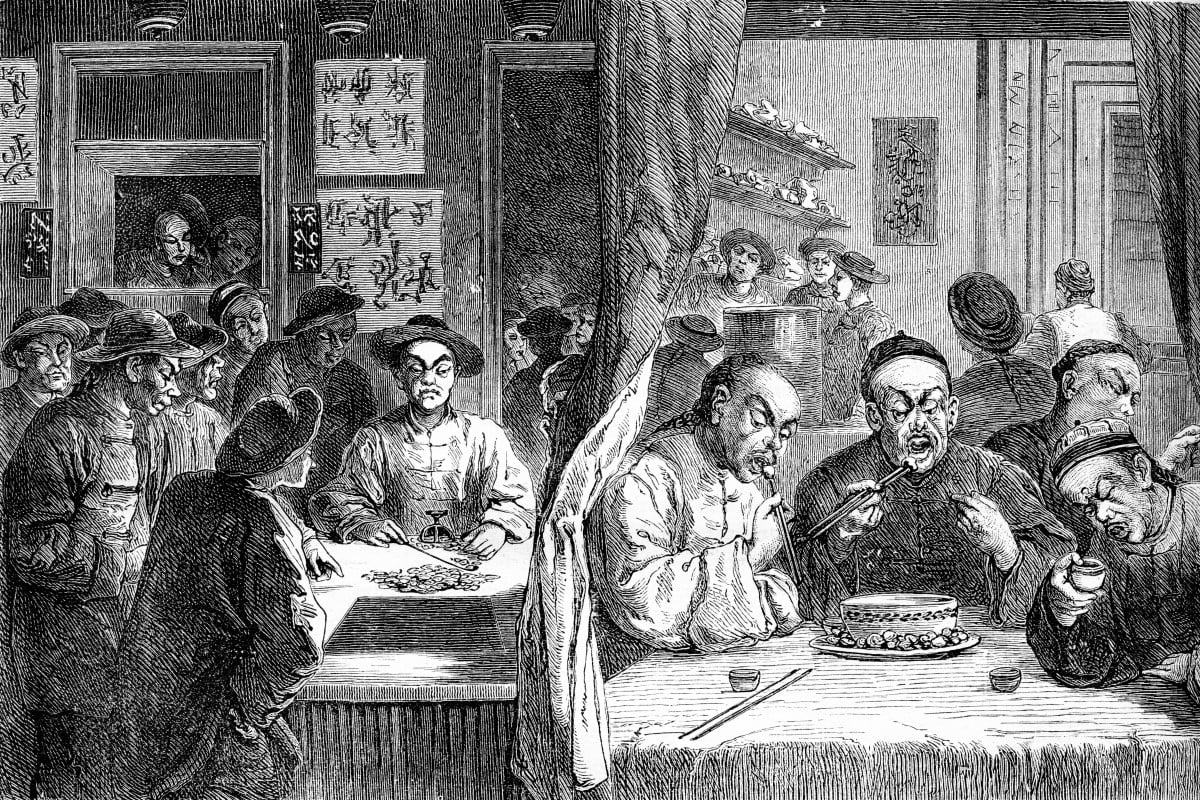

An engraving of a 19th-century Chinese opium den. Photo: Shutterstock

I am late to the Netflix game but in the weeks of not so splendid isolation, I have plunged down an enthralling rabbit hole from which extrication could be difficult when this is over. As part of my new-found addiction to television, I have been binge-watching Breaking Bad (2008-13), the US series about a cash-strapped, cancer-stricken chemistry teacher with a sideline in “cooking” methamphetamine.

Television and salty snacks aside, I am lucky to have never been addicted to harmful substances such as tobacco, alcohol or drugs. Having said that, I sympathise with the millions around the world who are battling addiction in all its debilitating forms, as well as their loved ones and carers. I know people who suffered devastating losses from addiction, including a relative who lost his life, and the effects on their families were heart-rending.

Opium has often been associated with drug dependence in imperial China. The first and second opium wars between China and Britain in the mid-19th century

gave shape to the Hong Kong we know today.

The history of opioid use in China goes back at least to the Tang dynasty (618-907), but “poppy tears” was not the only psychotropic substance known to the ancient Chinese.

During the Wei and Jin period (AD220-420), a substance called wu shi san (“five stone powder”) was popular among the elite. Its main ingredients were stalactites, fluorite, quartz, sulphur and halloysite clay or kaolin, which had been pulverised and mixed in specific proportions.

An immediate effect of taking wu shi san was a sudden rise in body temperature, which was mitigated by eating cold foods, taking cold baths or engaging in strenuous physical activities, such as walking long distances, to cool down the body through perspiration. There were records of users going naked in winter or eating snow because they were unbearably hot.

They also experienced an “opening of the spirit and mind”, which some have interpreted to mean hallucinations. And it had an aphrodisiac effect on men.

An early advocate of ingesting wu shi san was He Yan (AD196-249), son-in-law of the famous warlord Cao Cao and brother-in-law of the first emperor of the Wei dynasty. With his erudition, high social status and good looks, He Yan would be considered an “influencer” today.

Perhaps because of this “celebrity” status, the bizarre behaviour of He Yan and those taking the substance was celebrated as fashionable. Groups would take it together, and amuse or shock each other with outrageous conduct before falling into a stupor.

Long-term users exhibited incoherent speech and thought processes. They were also perpetually distracted. Physically, they suffered swellings and painful limbs, and some cases resulted in death. Wu shi sanwent out of fashion by the 5th century.

In 667, the Byzantine empire sent a mission to Emperor Gaozong of the Tang dynasty. Among the gifts they bore was a salve for the emperor’s frequent headaches, which the Chinese called di ye jia. This was theriaca, or theriac, a medical concoction invented by the ancient Greeks, which often contained opium for analgesic effect.

Soon the Chinese discovered the uses and pleasures of the substance derived from the milk of poppy, which centuries later, the British produced and sold in substantial quantities to the Chinese market.

During the Wei and Jin period (AD220-420), a substance called wu shi san (“five stone powder”) was popular among the elite. Its main ingredients were stalactites, fluorite, quartz, sulphur and halloysite clay or kaolin, which had been pulverised and mixed in specific proportions.

An immediate effect of taking wu shi san was a sudden rise in body temperature, which was mitigated by eating cold foods, taking cold baths or engaging in strenuous physical activities, such as walking long distances, to cool down the body through perspiration. There were records of users going naked in winter or eating snow because they were unbearably hot.

They also experienced an “opening of the spirit and mind”, which some have interpreted to mean hallucinations. And it had an aphrodisiac effect on men.

An early advocate of ingesting wu shi san was He Yan (AD196-249), son-in-law of the famous warlord Cao Cao and brother-in-law of the first emperor of the Wei dynasty. With his erudition, high social status and good looks, He Yan would be considered an “influencer” today.

Perhaps because of this “celebrity” status, the bizarre behaviour of He Yan and those taking the substance was celebrated as fashionable. Groups would take it together, and amuse or shock each other with outrageous conduct before falling into a stupor.

Long-term users exhibited incoherent speech and thought processes. They were also perpetually distracted. Physically, they suffered swellings and painful limbs, and some cases resulted in death. Wu shi sanwent out of fashion by the 5th century.

In 667, the Byzantine empire sent a mission to Emperor Gaozong of the Tang dynasty. Among the gifts they bore was a salve for the emperor’s frequent headaches, which the Chinese called di ye jia. This was theriaca, or theriac, a medical concoction invented by the ancient Greeks, which often contained opium for analgesic effect.

Soon the Chinese discovered the uses and pleasures of the substance derived from the milk of poppy, which centuries later, the British produced and sold in substantial quantities to the Chinese market.

---30---

No comments:

Post a Comment