Jon Ward Senior Political Correspondent, Yahoo News•April 25, 2020

WASHINGTON — President Trump’s mention Thursday of treating COVID-19 with ultraviolet light was part of a rambling digression that included speculation about administering disinfectants to patients, prompting confusion and alarm from medical experts.

The president’s invocation of pseudoscience — which he claimed on Friday had been a joke intended “sarcastically” to provoke reporters — overshadowed the news from the briefing about evidence, first reported last week by Yahoo News, that ultraviolet light does destroy the coronavirus. Researchers have shown it can be used to disinfect surfaces and kill viruses in ambient air in ways that could be used to reduce transmission in public spaces.

“Continuous very low dose-rate far-UVC light in indoor public locations is a promising, safe and inexpensive tool to reduce the spread of airborne-mediated microbial diseases,” wrote a team of researchers in a 2018 paper published in Scientific Reports.

Transmission of the coronavirus is thought to be more common through particles spread through the air than by contact with hard surfaces, but scientists are still working to understand how the virus spreads.

Yet if commercially available UV products were to mitigate some of the risk of contracting the coronavirus, that might help ease the transition out of a total lockdown. “This approach may help limit seasonal influenza epidemics, transmission of tuberculosis, as well as major pandemics,” the scientific researchers wrote in 2018.

The key is advances in UV lighting technology, specifically the advent of “far-UVC” lamps, which operate at a wavelength of 222 nanometers, a frequency that doesn’t penetrate skin or the outer layer of the human eye. Previously, disinfecting ultraviolet could not be used in public spaces because the wavelengths used, of 254 nanometers and up, can cause skin cancer and damage the eyes.

A pedestrian in Madrid on Friday. (Samuel de Roman/Getty Images)

By contrast, the 2018 paper found that “far-UVC light cannot penetrate even the outer (non living) layers of human skin or eye” but that “because bacteria and viruses are of micrometer or smaller dimensions, far-UVC can penetrate and inactivate them.”

David Brenner, director of Columbia University’s Center for Radiological Research, said earlier this week that far-UVC light “can be safely used in occupied public spaces, and it kills pathogens in the air before we can breathe them in.”

“Most approaches focus on fighting the virus once it has gotten into the body. Far-UVC is one of the very few approaches that has the potential to prevent the spread of viruses before they enter the body,” Brenner said.

A group of researchers at the Center for Radiological Research published a study in 2017 that “tested the hypothesis that there exists a narrow wavelength window in the far-UVC region, from around 200-222 nm, which is significantly harmful to bacteria, but without damaging cells in tissues.”

A UV sanitizer wand. (Kirk McKoy/Los Angeles Times via Getty Images)

A UV sanitizer wand. (Kirk McKoy/Los Angeles Times via Getty Images)The study found that far-UVC light kills pathogens “without the skin damaging effects associated with conventional germicidal UV exposure.”

Two other studies have examined the impact of far-UV light on skin using mice and found that “222 nm-UVC lamps can be safely used for sterilizing human skin.”

One company, Healthe, is already selling a few different UV light products, including far-UV lights meant to be used in public spaces. One is a downlight that can be installed in the ceiling of an average room. There is also a portal, similar to a metal detector, that claims it “inactivates over 90% of contaminants” if a person stands — arms up — inside the portal for 10 to 12 seconds.

The company says another way to use ultraviolet is to irradiate air as it passes through a sealed unit, like a building air-conditioning system. Since that doesn’t expose people to the rays, it can use different, more powerful wavelengths.

Despite these advances, public attention was distracted on Friday by the continued controversy over the president’s remarks the previous day.

President Trump at the coronavirus task force daily briefing on Thursday. (Mandel Ngan/AFP)

“I was asking a question sarcastically to reporters like you, just to see what would happen,” Trump said in the Oval Office. “I was asking a sarcastic question to the reporters in the room about disinfectant on the inside.”

He claimed he had not asked his medical experts in the White House briefing room on Thursday to look into injecting disinfectants into the human body. “I thought it was clear,” he said.

But the president’s comments on Thursday were anything but clear. His remarks were so jumbled it was hard to know what exactly he meant at times.

Trump spoke on Thursday just after the head of the Science and Technology Directorate at the Department of Homeland Security, Bill Bryan, had spoken to reporters about the impact of sunlight on coronavirus particles in outdoor public spaces, and had also mentioned testing bleach as a disinfectant.

“So, supposing we hit the body with a tremendous — whether it’s ultraviolet or just very powerful light — and I think you said that that hasn’t been checked, but you’re going to test it. And then I said, supposing you brought the light inside the body, which you can do either through the skin or in some other way, and I think you said you’re going to test that too. It sounds interesting.

“And then I see the disinfectant, where it knocks it out in a minute. One minute. And is there a way we can do something like that, by injection inside or almost a cleaning. Because you see it gets in the lungs and it does a tremendous number on the lungs,” Trump said. “So it would be interesting to check that. So, that, you’re going to have to use medical doctors with. But it sounds — it sounds interesting to me. So we’ll see. But the whole concept of the light, the way it kills it in one minute, that’s — that’s pretty powerful.”

Later in the briefing, Trump asked Dr. Deborah Birx, a medical expert on his coronavirus task force, about the possibility of using heat or light to treat a COVID-19 infection — rather than kill the coronavirus in the environment.

“Not as a treatment,” she replied.

Sunlight destroys coronavirus quickly, say US scientists

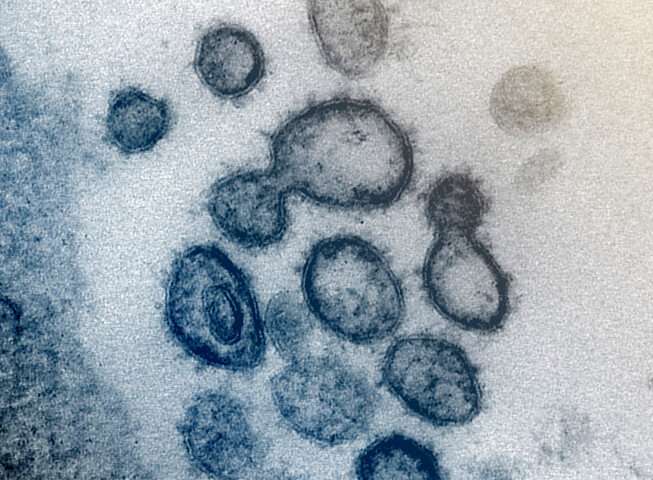

This transmission electron microscope image shows SARS-CoV-2 -- also known as 2019-nCoV, the virus that causes COVID-19 -- isolated from a patient in the US. Virus particles are shown emerging from the surface of cells cultured in the lab. The spikes on the outer edge of the virus particles give coronaviruses their name, crown-like. Credit: NIAID-RML

The new coronavirus is quickly destroyed by sunlight, according to new research announced by a senior US official on Thursday, though the study has not yet been made public and awaits external evaluation.

William Bryan, science and technology advisor to the Department of Homeland Security secretary, told reporters at the White House that government scientists had found ultraviolet rays had a potent impact on the pathogen, offering hope that its spread may ease over the summer.

"Our most striking observation to date is the powerful effect that solar light appears to have on killing the virus, both surfaces and in the air," he said.

"We've seen a similar effect with both temperature and humidity as well, where increasing the temperature and humidity or both is generally less favorable to the virus."

But the paper itself has not yet been released for review, making it difficult for independent experts to comment on how robust its methodology was.

It has long been known that ultraviolet light has a sterilizing effect, because the radiation damages the virus's genetic material and their ability to replicate.

A key question, however, will be what the intensity and wavelength of the UV light used in the experiment was and whether this accurately mimics natural light conditions in summer.

"It would be good to know how the test was done, and how the results were measured," Benjamin Neuman, chair of biological sciences at Texas A&M University-Texarkana, told AFP.

"Not that it would be done badly, just that there are several different ways to count viruses, depending on what aspect you are interested in studying."

Virus inactivated

Bryan shared a slide summarizing major findings of the experiment that was carried out at the National Biodefense Analysis and Countermeasures Center in Maryland.

It showed that the virus's half-life—the time taken for it to reduce to half its amount—was 18 hours when the temperature was 70 to 75 degrees Fahrenheit (21 to 24 degrees Celsius) with 20 percent humidity on a non-porous surface.

This includes things like door handles and stainless steel.

But the half-life dropped to six hours when humidity rose to 80 percent—and to just two minutes when sunlight was added to the equation.

When the virus was aerosolized—meaning suspended in the air—the half-life was one hour when the temperature was 70 to 75 degrees with 20 percent humidity.

In the presence of sunlight, this dropped to just one and a half minutes.

Bryan concluded that summer-like conditions "will create an environment (where) transmission can be decreased."

He added, though, that reduced spread did not mean the pathogen would be eliminated entirely and social distancing guidelines cannot be fully lifted.

"It would be irresponsible for us to say that we feel that the summer is just going to totally kill the virus and then if it's a free-for-all and that people ignore those guides," he said.

Previous work has also agreed that the virus fares better in cold and dry weather than it does in hot and humid conditions, and the lower rate of spread in southern hemisphere countries where it is early fall and still warm bear this out.

Australia, for example, has had just under 7,000 confirmed cases and 77 deaths—well below many northern hemisphere nations.

The reasons are thought to include that respiratory droplets remain airborne for longer in colder weather, and that viruses degrade more quickly on hotter surfaces, because a protective layer of fat that envelops them dries out faster.

US health authorities believe that even if COVID-19 cases slow over summer, the rate of infection is likely to increase again in fall and winter, in line with other seasonal viruses like the flu.

Explore furtherCoronavirus could become seasonal: top US scientist

© 2020 AFP

The new coronavirus is quickly destroyed by sunlight, according to new research announced by a senior US official on Thursday, though the study has not yet been made public and awaits external evaluation.

William Bryan, science and technology advisor to the Department of Homeland Security secretary, told reporters at the White House that government scientists had found ultraviolet rays had a potent impact on the pathogen, offering hope that its spread may ease over the summer.

"Our most striking observation to date is the powerful effect that solar light appears to have on killing the virus, both surfaces and in the air," he said.

"We've seen a similar effect with both temperature and humidity as well, where increasing the temperature and humidity or both is generally less favorable to the virus."

But the paper itself has not yet been released for review, making it difficult for independent experts to comment on how robust its methodology was.

It has long been known that ultraviolet light has a sterilizing effect, because the radiation damages the virus's genetic material and their ability to replicate.

A key question, however, will be what the intensity and wavelength of the UV light used in the experiment was and whether this accurately mimics natural light conditions in summer.

"It would be good to know how the test was done, and how the results were measured," Benjamin Neuman, chair of biological sciences at Texas A&M University-Texarkana, told AFP.

"Not that it would be done badly, just that there are several different ways to count viruses, depending on what aspect you are interested in studying."

Virus inactivated

Bryan shared a slide summarizing major findings of the experiment that was carried out at the National Biodefense Analysis and Countermeasures Center in Maryland.

It showed that the virus's half-life—the time taken for it to reduce to half its amount—was 18 hours when the temperature was 70 to 75 degrees Fahrenheit (21 to 24 degrees Celsius) with 20 percent humidity on a non-porous surface.

This includes things like door handles and stainless steel.

But the half-life dropped to six hours when humidity rose to 80 percent—and to just two minutes when sunlight was added to the equation.

When the virus was aerosolized—meaning suspended in the air—the half-life was one hour when the temperature was 70 to 75 degrees with 20 percent humidity.

In the presence of sunlight, this dropped to just one and a half minutes.

Bryan concluded that summer-like conditions "will create an environment (where) transmission can be decreased."

He added, though, that reduced spread did not mean the pathogen would be eliminated entirely and social distancing guidelines cannot be fully lifted.

"It would be irresponsible for us to say that we feel that the summer is just going to totally kill the virus and then if it's a free-for-all and that people ignore those guides," he said.

Previous work has also agreed that the virus fares better in cold and dry weather than it does in hot and humid conditions, and the lower rate of spread in southern hemisphere countries where it is early fall and still warm bear this out.

Australia, for example, has had just under 7,000 confirmed cases and 77 deaths—well below many northern hemisphere nations.

The reasons are thought to include that respiratory droplets remain airborne for longer in colder weather, and that viruses degrade more quickly on hotter surfaces, because a protective layer of fat that envelops them dries out faster.

US health authorities believe that even if COVID-19 cases slow over summer, the rate of infection is likely to increase again in fall and winter, in line with other seasonal viruses like the flu.

Explore furtherCoronavirus could become seasonal: top US scientist

© 2020 AFP

No comments:

Post a Comment