ArtSeen

Against, Again: Art Under Attack in Brazil

By Sumeja Tulic

Jaime Lauriano, America, 2020. Drawing made with black pemba (chalk used in rituals of Umbanda), dermatographic pencil, charcoal and golden self-adhesive high tack tape on cotton. 150 x 160 cm. Courtesy the artist. Photo: Alex Korolkovas/Courtesy of AnnexB.

ON VIEW

ON VIEW

Anya and Andrew Shiva Gallery

New York

What happens when nostalgia and the future collide? A very complicated present, befitting a group show. Against, Again: Art Under Attack in Brazil presents the work of more than 30 artists whose practices respond to the seemingly cyclical waves of authoritarianism brought back into full swing in Brazil with the election of the far-right president Jair Bolsonaro. Since his inauguration in January of 2019, Bolsonaro, a retired military officer and admirer and ally of President Trump, has begun a steady attack against the Brazilian democracy and its institution, threatening and censuring political opposition, activists, intellectuals, and artists. In addition to being a vocal opponent of same-sex marriage, environmental regulations, abortion, affirmative action, immigration, drug liberalization, land reform, and secularism, Bolsonaro is a staunch defender of the Brazilian military dictatorship (1964–1985) and its torture practices.

The show begins with America: democracia racial, melting pot and pureza de razas (2019) by São Paulo based Jaime Lauriano, whose work often deals with institutional violence and historical traumas. Here, he resurrects the aesthetics of colonial cartography and “the discovery of the new world” on a white textile, drawing the Americas with the black chalk used in the rituals of a syncretic Afro-Brazilian religion. America distinguishes itself from colonial cartography by concretizing, in language, with honesty and irony, the ideals and deceptions of the settler-colonial expansion and its genocidal practices. In Lauriano’s map, instead of the Atlantic Ocean the viewer reads in Portuguese "Racial Democracy" while "Race Purity" takes the place of the Pacific Ocean. “The Melting Pot” is spelled out in quaint typography over the lands of North America.

While Lauriano’s work examines the production and representations of history, the decades-long practice of Maria Thereza Alves has been concerned with the detrimental effects of the Portuguese imperialism on the indigenous peoples of Brazil as well as the impact of the Spanish conquest on the Americas. The show features two iterations of Alves’s meeting with her mentor, indigenous leader Tupã-Y Guaraní (Marçal de Souza). The first, from 1980, is a black-and-white photograph of Guaraní standing at the edge of his tribe’s land in the interior state of Mato Grosso do Sul, pointing at the mountain that once marked its border. The other documentation Alves presents is an audio recording of a conversation she had with Guaraní, also in 1980, which is played as the soundtrack of a single-frame video made of the photograph, which has been colorized, of Guaraní pointing at the mountain. During their discussion, Guaraní explains that a union of indigenous peoples has been formed and encourages Alves to join the fight for indigenous rights. Three years after their meeting, in 1983, Guaraní was brutally murdered by a Euro-Brazilian landowner wanting his tribal lands.

New York

What happens when nostalgia and the future collide? A very complicated present, befitting a group show. Against, Again: Art Under Attack in Brazil presents the work of more than 30 artists whose practices respond to the seemingly cyclical waves of authoritarianism brought back into full swing in Brazil with the election of the far-right president Jair Bolsonaro. Since his inauguration in January of 2019, Bolsonaro, a retired military officer and admirer and ally of President Trump, has begun a steady attack against the Brazilian democracy and its institution, threatening and censuring political opposition, activists, intellectuals, and artists. In addition to being a vocal opponent of same-sex marriage, environmental regulations, abortion, affirmative action, immigration, drug liberalization, land reform, and secularism, Bolsonaro is a staunch defender of the Brazilian military dictatorship (1964–1985) and its torture practices.

The show begins with America: democracia racial, melting pot and pureza de razas (2019) by São Paulo based Jaime Lauriano, whose work often deals with institutional violence and historical traumas. Here, he resurrects the aesthetics of colonial cartography and “the discovery of the new world” on a white textile, drawing the Americas with the black chalk used in the rituals of a syncretic Afro-Brazilian religion. America distinguishes itself from colonial cartography by concretizing, in language, with honesty and irony, the ideals and deceptions of the settler-colonial expansion and its genocidal practices. In Lauriano’s map, instead of the Atlantic Ocean the viewer reads in Portuguese "Racial Democracy" while "Race Purity" takes the place of the Pacific Ocean. “The Melting Pot” is spelled out in quaint typography over the lands of North America.

While Lauriano’s work examines the production and representations of history, the decades-long practice of Maria Thereza Alves has been concerned with the detrimental effects of the Portuguese imperialism on the indigenous peoples of Brazil as well as the impact of the Spanish conquest on the Americas. The show features two iterations of Alves’s meeting with her mentor, indigenous leader Tupã-Y Guaraní (Marçal de Souza). The first, from 1980, is a black-and-white photograph of Guaraní standing at the edge of his tribe’s land in the interior state of Mato Grosso do Sul, pointing at the mountain that once marked its border. The other documentation Alves presents is an audio recording of a conversation she had with Guaraní, also in 1980, which is played as the soundtrack of a single-frame video made of the photograph, which has been colorized, of Guaraní pointing at the mountain. During their discussion, Guaraní explains that a union of indigenous peoples has been formed and encourages Alves to join the fight for indigenous rights. Three years after their meeting, in 1983, Guaraní was brutally murdered by a Euro-Brazilian landowner wanting his tribal lands.

Maria Thereza Alves, Marçal Tupã Y (Tupã-Y Guaraní, Marçal de Souza), 1980. Courtesy the artist. Photo: Alex Korolkovas/Courtesy of AnnexB.

Despite a recent drop in murders in Brazil, violent crimes continue to plague the country—a problem compounded by the use of lethal force by Brazilian police. An Apology to Elephants (2019), a video by Brooklyn-based Anna Parisi (b. 1984), is dedicated to five children, ranging from 8 to 12 years old, who were killed in Rio de Janeiro’s favelas during police raids. The video begins with footage of a baby elephant, “…so cute, young and plump… docile eyes…so dark,” the narrator says, walking down a road, before the video shifts its tone. An older elephant then is punished by a trainer, a white, middle-aged woman. The training sequence dissolves into footage of police breaking into a favela, gathering boys and men, hitting and degrading their black and brown bodies, which the police body cameras render gray and blue.

Despite a recent drop in murders in Brazil, violent crimes continue to plague the country—a problem compounded by the use of lethal force by Brazilian police. An Apology to Elephants (2019), a video by Brooklyn-based Anna Parisi (b. 1984), is dedicated to five children, ranging from 8 to 12 years old, who were killed in Rio de Janeiro’s favelas during police raids. The video begins with footage of a baby elephant, “…so cute, young and plump… docile eyes…so dark,” the narrator says, walking down a road, before the video shifts its tone. An older elephant then is punished by a trainer, a white, middle-aged woman. The training sequence dissolves into footage of police breaking into a favela, gathering boys and men, hitting and degrading their black and brown bodies, which the police body cameras render gray and blue.

Berna Reale, Camuflagem #01 (Camouflage #01), 2018. Inkjet print with mineral pigment on paper, 100 x 150 cm. Courtesy the artist and Galeria Nara Roesler, São Paulo and New York. Photo: Alex Korolkovas/Courtesy of AnnexB.

Also on view is Camuflagem #01 (2018), a photograph by the performance artist Berna Reale (b.1965), who is known for using her body in constructing reflections on social conflicts and disparities. For Camuflagem #01, Reale wears a military uniform while pushing a wagon carrying bundles that are shaped like human corpses and made from sheets used to cover victims of violence that Reale, who is also a forensic investigator, sourced from her colleagues working in police departments. In Camuflagem #01, Reale's back is to the camera—the bodily position of a perfect target.

The show also includes Inserções em circuitos ideológicos: Projeto cédula ("Insertions into Ideological Circuits: Banknote Project"), the work of the acclaimed conceptual artist and sculptor Cildo Meireles (b.1948). For this installation, made in 1970, Meireles stamped official banknotes with subversive messages and then returned them to regular circulation, including one asking "Quem Matou Herzog?" or "Who Killed Herzog?" The question refers to the death by torture of the journalist Vlado Herzog, a vocal opponent of the military dictatorship, by the police. Herzog’s murder was officially reported as suicide. The Banknote Project exemplifies Meireles’s practice of producing unexpected opportunities for viewer engagement as he did again in response to the 2018 murder of Marielle Franco, a Rio de Janeiro councilwoman, feminist, human rights activist, and outspoken critic of police brutality and extrajudicial killings. In 2019, two former police officers were arrested and charged with her murder. Before their arrest, both suspects had pictures taken with Bolsonaro. Recently, several Brazilian media outlets reported that the police were investigating possible ties of Bolsonaro’s second son, Carlos, to the murder.

Originally the title of a book by the Viennese-born writer Stefan Zweig, “Brazil is the land of the future,” is a repeated refrain amongst Brazilians envisioning what is to come as a society marked by plurality, diversity, and economic prosperity. In the past few years, the latter part of the phrase, "and always will be," has been replaced by "but that future never arrives." Between the idealism and resolve of the first and irony of the second accompanying phrase is a positive-bias. This positive-bias, common to all people and not just Brazilians, refuses to acknowledge the future as an adverse condition immune to the promises of historical and technological progress. Some of that future is the present, quarantined life sustaining the world.

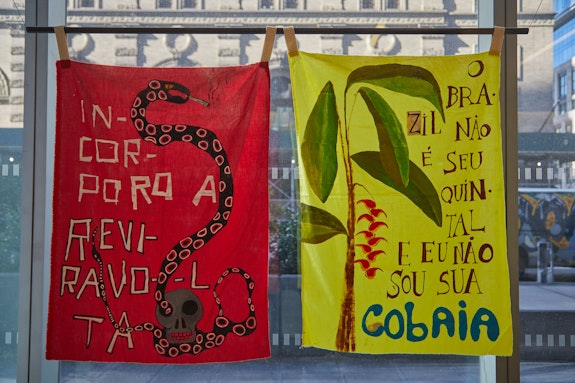

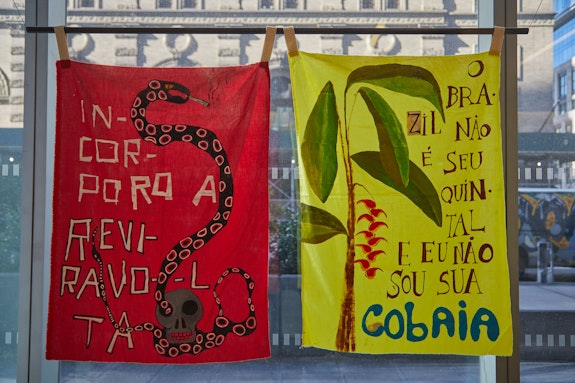

#CóleraAlegria, Selection of protest flags and slideshow with images of protests, 2016–ongoing. Dimensions variable. Courtesy the artists. Photo: Alex Korolkovas/Courtesy of AnnexB.

#CóleraAlegria, Selection of protest flags and slideshow with images of protests, 2016–ongoing. Dimensions variable. Courtesy the artists. Photo: Alex Korolkovas/Courtesy of AnnexB.

On the way out of the gallery are works by the collaborative action project #CóleraAlegria, which creates banners, posters, and flags for political demonstrations and online campaigns. On the day the gallery reopened after closing for one day because of the COVID-19 outbreak, between two gallery shifts, the front desk was empty. Befittingly to the moment and scene, #CóleraAlegria's poster hung above the desk and the empty chair: "Democracy, what time will she return?"

ContributorSumeja Tulic

is a contributor to the Rail.

Also on view is Camuflagem #01 (2018), a photograph by the performance artist Berna Reale (b.1965), who is known for using her body in constructing reflections on social conflicts and disparities. For Camuflagem #01, Reale wears a military uniform while pushing a wagon carrying bundles that are shaped like human corpses and made from sheets used to cover victims of violence that Reale, who is also a forensic investigator, sourced from her colleagues working in police departments. In Camuflagem #01, Reale's back is to the camera—the bodily position of a perfect target.

The show also includes Inserções em circuitos ideológicos: Projeto cédula ("Insertions into Ideological Circuits: Banknote Project"), the work of the acclaimed conceptual artist and sculptor Cildo Meireles (b.1948). For this installation, made in 1970, Meireles stamped official banknotes with subversive messages and then returned them to regular circulation, including one asking "Quem Matou Herzog?" or "Who Killed Herzog?" The question refers to the death by torture of the journalist Vlado Herzog, a vocal opponent of the military dictatorship, by the police. Herzog’s murder was officially reported as suicide. The Banknote Project exemplifies Meireles’s practice of producing unexpected opportunities for viewer engagement as he did again in response to the 2018 murder of Marielle Franco, a Rio de Janeiro councilwoman, feminist, human rights activist, and outspoken critic of police brutality and extrajudicial killings. In 2019, two former police officers were arrested and charged with her murder. Before their arrest, both suspects had pictures taken with Bolsonaro. Recently, several Brazilian media outlets reported that the police were investigating possible ties of Bolsonaro’s second son, Carlos, to the murder.

Originally the title of a book by the Viennese-born writer Stefan Zweig, “Brazil is the land of the future,” is a repeated refrain amongst Brazilians envisioning what is to come as a society marked by plurality, diversity, and economic prosperity. In the past few years, the latter part of the phrase, "and always will be," has been replaced by "but that future never arrives." Between the idealism and resolve of the first and irony of the second accompanying phrase is a positive-bias. This positive-bias, common to all people and not just Brazilians, refuses to acknowledge the future as an adverse condition immune to the promises of historical and technological progress. Some of that future is the present, quarantined life sustaining the world.

#CóleraAlegria, Selection of protest flags and slideshow with images of protests, 2016–ongoing. Dimensions variable. Courtesy the artists. Photo: Alex Korolkovas/Courtesy of AnnexB.

#CóleraAlegria, Selection of protest flags and slideshow with images of protests, 2016–ongoing. Dimensions variable. Courtesy the artists. Photo: Alex Korolkovas/Courtesy of AnnexB.On the way out of the gallery are works by the collaborative action project #CóleraAlegria, which creates banners, posters, and flags for political demonstrations and online campaigns. On the day the gallery reopened after closing for one day because of the COVID-19 outbreak, between two gallery shifts, the front desk was empty. Befittingly to the moment and scene, #CóleraAlegria's poster hung above the desk and the empty chair: "Democracy, what time will she return?"

ContributorSumeja Tulic

is a contributor to the Rail.

No comments:

Post a Comment