Crash course in saving the Earth: Chinese simulation stops asteroid strike without using nukes

Computer model shows how potentially hazardous asteroids can be knocked off course and out of harm’s way using an ‘enhanced kinetic impactor’ spacecraft

Nasa advocates the use of nuclear weapons to neutralise such threats, but the option is not without controversy

Stephen Chen in Beijing Published: 29 May, 2020

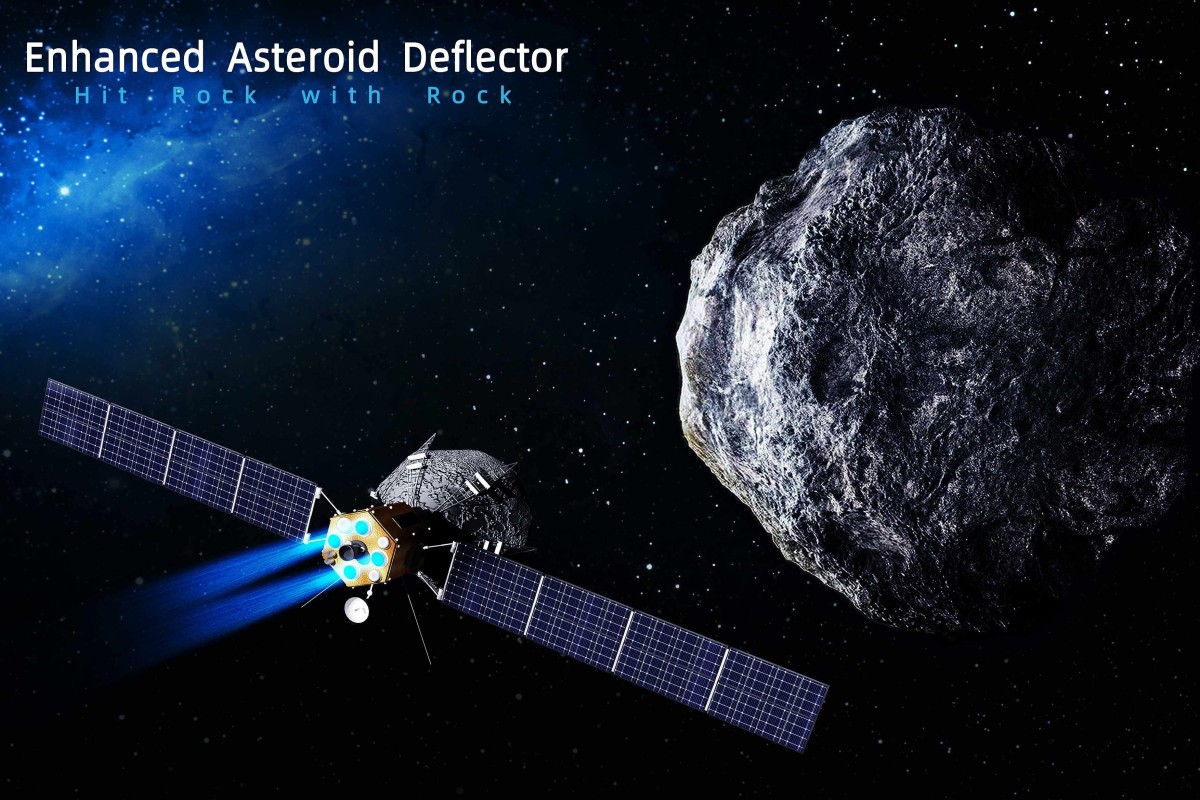

In the computer simulation, EKI’s mission to save the Earth takes just under four years. Photo: Handout

Chinese scientists have come up with an ingenious alternative to nuclear obliteration for neutralising the threat of potentially Earth-shattering asteroids – staging a cosmic collision to knock the offending rocky mass off course.

Ever since discovering that a 10km-diameter asteroid was most likely to blame for the

extinction of the dinosaurs 66 million years ago, the world’s scientific community has been looking for ways to ensure the human race does not suffer the same fate.

While Nasa has long advocated the use of nuclear weapons to neutralise the threat of so-called potentially hazardous asteroids, detonating a warhead in space is not without its problems or controversy.

The alternative, according to a team from the Chinese Academy of Sciences, is to send an unmanned spacecraft out to meet the incoming threat and deflect it out of harm’s way.

However, to have sufficient heft to do that, the spacecraft must first bulk up, which it does by collecting rocks from a near-Earth asteroid en route.

An artist’s impression shows how EKI gathers weight and makes a beeline for the incoming asteroid. Photo: Handout

The team successfully tested their theory using a computer simulation, the results of which were published in a recent edition of the peer-reviewed online journal Scientific Reports.

In the imagined mission, an eight-tonne spacecraft – known as an enhanced kinetic impactor (EKI) – is launched into space on October 7, 2021 aboard a

Long March 5 rocket. More than two years later, EKI rendezvouses with the near-Earth asteroid “2017 HF”, and using a robotic arm relieves it of about 200 tonnes of its rocky mass.

With the extra weight on board, EKI sets its sights on Apophis – a real asteroid with a diameter of about 370 metres that is considered one of the most potentially hazardous to human life – and on September 23, 2025 slams into it a relative speed of more than 42,000km/h (26,000mph).

The force of the collision is enough to push Apophis more than 1,800km off course – which in the simulation would have ended with a direct hit on Planet Earth – and the world is saved.

Li Mingtao, the paper’s lead author, said the team wanted to find an alternative to “controversial nuclear explosions” and came up with the EKI concept after being inspired by the Asteroid Redirect Mission launched by former US president Barack Obama in 2015, but cancelled two years later by Donald Trump.

A Beijing-based space scientist who was not involved in the simulation and asked not to be named praised the EKI project for its “smart strategy of turning one asteroid against another”.

Not even the world’s most powerful rocket could send a 200-tonne spacecraft into deep space, he said, adding that the EKI and nuclear options were as different as tai chi and boxing.

“It [EKI] is more about trapping, slipping and deflecting the attack than throwing punches,” he said.

However, despite the mission’s simulated success, the actual technology needed to grab and secure rocks of up to 10 metres across from a passing asteroid had yet to be tested in the real world, he said.

Professor Wu Yunzhao, a researcher in the laboratory of planetary sciences at the Purple Mountain Observatory in Nanjing, said that while China was ready to play a key role in dealing with global threats like asteroid strikes, the issue demanded international cooperation.

“The threat of an asteroid impact is real and serious, and preventing it requires long-term planning and preparation,” he said.

“It also needs global cooperation because no country has the ability and resources to do it alone.”

Stephen Chen investigates major research projects in China, a new power house of scientific and technological innovation. He has worked for the Post since 2006. He is an alumnus of Shantou University, the Hong Kong University of Science and Technology, and the Semester at Sea programme which he attended with a full scholarship from the Seawise Foundation.

Computer model shows how potentially hazardous asteroids can be knocked off course and out of harm’s way using an ‘enhanced kinetic impactor’ spacecraft

Nasa advocates the use of nuclear weapons to neutralise such threats, but the option is not without controversy

Stephen Chen in Beijing Published: 29 May, 2020

In the computer simulation, EKI’s mission to save the Earth takes just under four years. Photo: Handout

Chinese scientists have come up with an ingenious alternative to nuclear obliteration for neutralising the threat of potentially Earth-shattering asteroids – staging a cosmic collision to knock the offending rocky mass off course.

Ever since discovering that a 10km-diameter asteroid was most likely to blame for the

extinction of the dinosaurs 66 million years ago, the world’s scientific community has been looking for ways to ensure the human race does not suffer the same fate.

While Nasa has long advocated the use of nuclear weapons to neutralise the threat of so-called potentially hazardous asteroids, detonating a warhead in space is not without its problems or controversy.

The alternative, according to a team from the Chinese Academy of Sciences, is to send an unmanned spacecraft out to meet the incoming threat and deflect it out of harm’s way.

However, to have sufficient heft to do that, the spacecraft must first bulk up, which it does by collecting rocks from a near-Earth asteroid en route.

An artist’s impression shows how EKI gathers weight and makes a beeline for the incoming asteroid. Photo: Handout

The team successfully tested their theory using a computer simulation, the results of which were published in a recent edition of the peer-reviewed online journal Scientific Reports.

In the imagined mission, an eight-tonne spacecraft – known as an enhanced kinetic impactor (EKI) – is launched into space on October 7, 2021 aboard a

Long March 5 rocket. More than two years later, EKI rendezvouses with the near-Earth asteroid “2017 HF”, and using a robotic arm relieves it of about 200 tonnes of its rocky mass.

With the extra weight on board, EKI sets its sights on Apophis – a real asteroid with a diameter of about 370 metres that is considered one of the most potentially hazardous to human life – and on September 23, 2025 slams into it a relative speed of more than 42,000km/h (26,000mph).

The force of the collision is enough to push Apophis more than 1,800km off course – which in the simulation would have ended with a direct hit on Planet Earth – and the world is saved.

Li Mingtao, the paper’s lead author, said the team wanted to find an alternative to “controversial nuclear explosions” and came up with the EKI concept after being inspired by the Asteroid Redirect Mission launched by former US president Barack Obama in 2015, but cancelled two years later by Donald Trump.

A Beijing-based space scientist who was not involved in the simulation and asked not to be named praised the EKI project for its “smart strategy of turning one asteroid against another”.

Not even the world’s most powerful rocket could send a 200-tonne spacecraft into deep space, he said, adding that the EKI and nuclear options were as different as tai chi and boxing.

“It [EKI] is more about trapping, slipping and deflecting the attack than throwing punches,” he said.

However, despite the mission’s simulated success, the actual technology needed to grab and secure rocks of up to 10 metres across from a passing asteroid had yet to be tested in the real world, he said.

Professor Wu Yunzhao, a researcher in the laboratory of planetary sciences at the Purple Mountain Observatory in Nanjing, said that while China was ready to play a key role in dealing with global threats like asteroid strikes, the issue demanded international cooperation.

“The threat of an asteroid impact is real and serious, and preventing it requires long-term planning and preparation,” he said.

“It also needs global cooperation because no country has the ability and resources to do it alone.”

Stephen Chen investigates major research projects in China, a new power house of scientific and technological innovation. He has worked for the Post since 2006. He is an alumnus of Shantou University, the Hong Kong University of Science and Technology, and the Semester at Sea programme which he attended with a full scholarship from the Seawise Foundation.

No comments:

Post a Comment