HAPPY CINQUE DE MAYO

LOVED BY SURREALISTS AND REVOLUTIONARIES AROUND THE GLOBE

Jose Guadalupe Posada, was a lithographer and print maker in Mexico's pre-Revolution times; he is best known for the creation of La Calaca Garbancera, that later became La Catrina, the iconic skeleton lady used during the Day of the Dead celebrations and many folk art styles. Posada is considered by scholars the father of Mexican modern art.

Jose Guadalupe Posada's Work and Life

Posada was born on February 2, 1852 in Aguascalientes, a city in central Mexico, to Petra Aguilar a homemaker and German Posada a baker, both illiterate.

He received elemental education from his brother Jose Cirilo, 12 years his senior who was an elementary school teacher.

Jose Cirilo urged him to work at a kinder garden where Posada spent most of the time drawing portraits of the children and illustrations about the subjects taught to them.

Because his drawing ability was evident he pursued education at the art academy of Aguascalientes which he attended for a brief time.

In 1868 Posada began working at José Trinidad Pedroza's printing house, one of the best in the country.

Pedroza taught Posada the printmaking techniques for lithography and engraving on wood and metal. Three years later, at age 19, Posada was head cartoonist of El Jicote (The Wasp)

a critical newspaper edited by Pedroza with whom Posada became friends and later business partner.

With Posada's help Pedroza opened a second printing house in Leon, Guanajuato. There Jose Guadalupe got married in 1875 to Maria de Jesus Vela with whom he had a child who died at a young age.

Posada did very well illustrating newspapers, magazines, books and commercial items such as cigarette and match boxes and eventually dissolved the partnership with Pedroza. In 1888 a cataclysmic flood struck the city forcing Posada to move to Mexico City.

Right after he arrived to Mexico City he published a series of drawings in the weekly newspaper La Juventud Literaria (The Literary Youth) which were presented by Ireneo Paz with the following introduction:

"Our readers ought to appreciate the imagination of Jose Guadalupe Posada who has drawn these small drawings in his free time. We are very pleased to praise who deserves to be praised and we guess he will become the best Mexican cartoonist. We are waiting for his masterpiece and the praising he will receive from the press and the smart people. Until then we congratulate this young artist and wish him to continue on this path."

Posada opened a humble workshop where he engraved historic scenes, recipe books, news, songbooks, board games, stories, love letters, religious images, etc. The Mexican capital had then 350,000 inhabitants, 80% of them illiterate, therefore illustrations were a great way to communicate.

Posada's most prolific and important work was done in the printing shop of publisher Antonio Vanegas Arroyo, where he began as a staff artist around 1890 and soon became the publisher's chief artist.

There Posada met Manuel Manila, engraver who taught him how to create a rich shade of grays and a more precise and delicate drawing. Posada then abandoned lithography and began to work first with engraving on type metal and later with relief etching on zinc which gave him more flexibility.

Vanegas Arroyo, poet Constancio Suárez and Posada teamed up to publish cheap one-page leaflets with brightly printed, graphics that reported the news and social issues of the day.

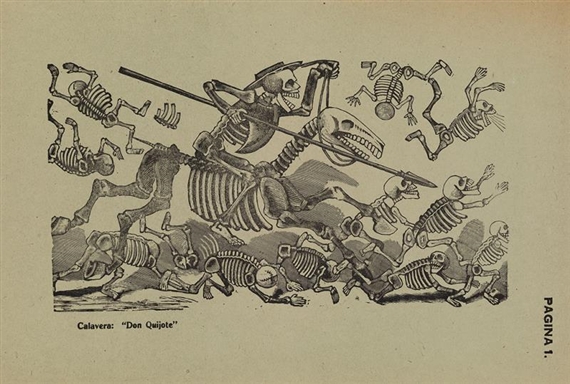

They created the calaveras tradition, satirical rhymes illustrated with skulls and skeletons that usually refer to the hypothetic death circumstances of a politician or celebrity. Thanks to Posada's illustrations these verses became an economical success. It was in this gender that Posada created La Calaca Garbancera later known as La Catrina.

He described with originality the spirit of the Mexicans: the political matters, daily life, the terror for the end of the century and for the end of the world, besides the natural disasters, the religious beliefs and popular horror stories; a tireless worker he made 15,000 engravings during his life.

Jose Guadalupe Posada died a widower and without issue on January 20, 1913; he was buried in a common grave at the Dolores cemetery in Mexico City.

Posada, Precursor of Mexican Modern Art

Scholars and artists in Mexico and abroad consider Posada the precursor of Mexican modern art:

Diego Rivera deemed Posada his artistic father and compared him to Goya and Callot, he dedicated him his mural Sunday Evening's Dream, that depicts Posada in the center of the masterpiece holding hands with La Calaca Garbancera, who Rivera named La Catrina.

Painter Jose Clemente Orozco claimed that watching Posada working in at his workshop awoke him to the art of painting.

Mexican poet Octavio Paz, Nobel Prize winner, described his technique like a minimum of lines and a maximum of expression and said about him: "By birthright Posada belongs to expressionism but unlike most expressionists he never took himself seriously".

Posada's Museum in Aguascalientes

Painter, muralist and engraver Luis Seoane said about Posada: "Mexico, who has the most beautiful history in America, the most extraordinary monuments built before and after the Spanish Colony, the most rebellious blood and the weirdest talents has too with Jose Guadalupe Posada the greatest engraver in America, deeply Mexican thus highly universal"

Historian and museographer Fernando Gamboa wrote about him in 1944: "Jose Guadalupe Posada is a popular artist in the deepest and highest sense of the word; popular because of his humble origin; popular, because of the definite class feeling he brings into each of his works; popular, because he was not an artist without antecedents, a phenomenon foreign to the world in which he lived, but rather the outburst of the feelings of a striving people; popular, because of the way he studied and lived in direct contact with life and the way in which he conscientiously listened to the demands of the Mexican people."

LOVED BY SURREALISTS AND REVOLUTIONARIES AROUND THE GLOBE

Jose Guadalupe Posada, was a lithographer and print maker in Mexico's pre-Revolution times; he is best known for the creation of La Calaca Garbancera, that later became La Catrina, the iconic skeleton lady used during the Day of the Dead celebrations and many folk art styles. Posada is considered by scholars the father of Mexican modern art.

Jose Guadalupe Posada's Work and Life

Posada was born on February 2, 1852 in Aguascalientes, a city in central Mexico, to Petra Aguilar a homemaker and German Posada a baker, both illiterate.

He received elemental education from his brother Jose Cirilo, 12 years his senior who was an elementary school teacher.

Jose Cirilo urged him to work at a kinder garden where Posada spent most of the time drawing portraits of the children and illustrations about the subjects taught to them.

Because his drawing ability was evident he pursued education at the art academy of Aguascalientes which he attended for a brief time.

In 1868 Posada began working at José Trinidad Pedroza's printing house, one of the best in the country.

Pedroza taught Posada the printmaking techniques for lithography and engraving on wood and metal. Three years later, at age 19, Posada was head cartoonist of El Jicote (The Wasp)

a critical newspaper edited by Pedroza with whom Posada became friends and later business partner.

With Posada's help Pedroza opened a second printing house in Leon, Guanajuato. There Jose Guadalupe got married in 1875 to Maria de Jesus Vela with whom he had a child who died at a young age.

Posada did very well illustrating newspapers, magazines, books and commercial items such as cigarette and match boxes and eventually dissolved the partnership with Pedroza. In 1888 a cataclysmic flood struck the city forcing Posada to move to Mexico City.

Right after he arrived to Mexico City he published a series of drawings in the weekly newspaper La Juventud Literaria (The Literary Youth) which were presented by Ireneo Paz with the following introduction:

"Our readers ought to appreciate the imagination of Jose Guadalupe Posada who has drawn these small drawings in his free time. We are very pleased to praise who deserves to be praised and we guess he will become the best Mexican cartoonist. We are waiting for his masterpiece and the praising he will receive from the press and the smart people. Until then we congratulate this young artist and wish him to continue on this path."

Posada opened a humble workshop where he engraved historic scenes, recipe books, news, songbooks, board games, stories, love letters, religious images, etc. The Mexican capital had then 350,000 inhabitants, 80% of them illiterate, therefore illustrations were a great way to communicate.

Posada's most prolific and important work was done in the printing shop of publisher Antonio Vanegas Arroyo, where he began as a staff artist around 1890 and soon became the publisher's chief artist.

There Posada met Manuel Manila, engraver who taught him how to create a rich shade of grays and a more precise and delicate drawing. Posada then abandoned lithography and began to work first with engraving on type metal and later with relief etching on zinc which gave him more flexibility.

Vanegas Arroyo, poet Constancio Suárez and Posada teamed up to publish cheap one-page leaflets with brightly printed, graphics that reported the news and social issues of the day.

They created the calaveras tradition, satirical rhymes illustrated with skulls and skeletons that usually refer to the hypothetic death circumstances of a politician or celebrity. Thanks to Posada's illustrations these verses became an economical success. It was in this gender that Posada created La Calaca Garbancera later known as La Catrina.

He described with originality the spirit of the Mexicans: the political matters, daily life, the terror for the end of the century and for the end of the world, besides the natural disasters, the religious beliefs and popular horror stories; a tireless worker he made 15,000 engravings during his life.

Jose Guadalupe Posada died a widower and without issue on January 20, 1913; he was buried in a common grave at the Dolores cemetery in Mexico City.

Posada, Precursor of Mexican Modern Art

Scholars and artists in Mexico and abroad consider Posada the precursor of Mexican modern art:

Diego Rivera deemed Posada his artistic father and compared him to Goya and Callot, he dedicated him his mural Sunday Evening's Dream, that depicts Posada in the center of the masterpiece holding hands with La Calaca Garbancera, who Rivera named La Catrina.

Painter Jose Clemente Orozco claimed that watching Posada working in at his workshop awoke him to the art of painting.

Mexican poet Octavio Paz, Nobel Prize winner, described his technique like a minimum of lines and a maximum of expression and said about him: "By birthright Posada belongs to expressionism but unlike most expressionists he never took himself seriously".

Posada's Museum in Aguascalientes

Painter, muralist and engraver Luis Seoane said about Posada: "Mexico, who has the most beautiful history in America, the most extraordinary monuments built before and after the Spanish Colony, the most rebellious blood and the weirdest talents has too with Jose Guadalupe Posada the greatest engraver in America, deeply Mexican thus highly universal"

Historian and museographer Fernando Gamboa wrote about him in 1944: "Jose Guadalupe Posada is a popular artist in the deepest and highest sense of the word; popular because of his humble origin; popular, because of the definite class feeling he brings into each of his works; popular, because he was not an artist without antecedents, a phenomenon foreign to the world in which he lived, but rather the outburst of the feelings of a striving people; popular, because of the way he studied and lived in direct contact with life and the way in which he conscientiously listened to the demands of the Mexican people."

SOME OF MY FAVORITES

No comments:

Post a Comment