By WILLIAM MORRIS

wmorris@owatonna.com

Aug 25, 2017

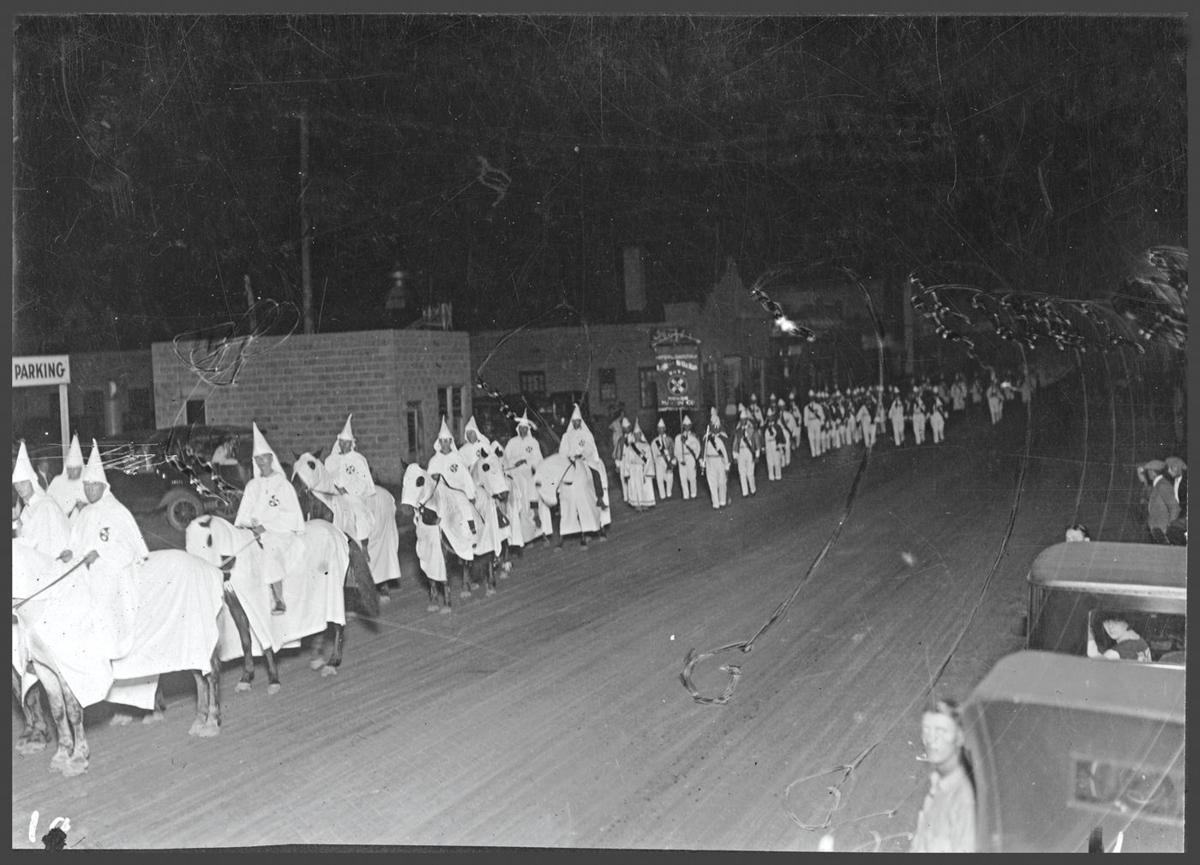

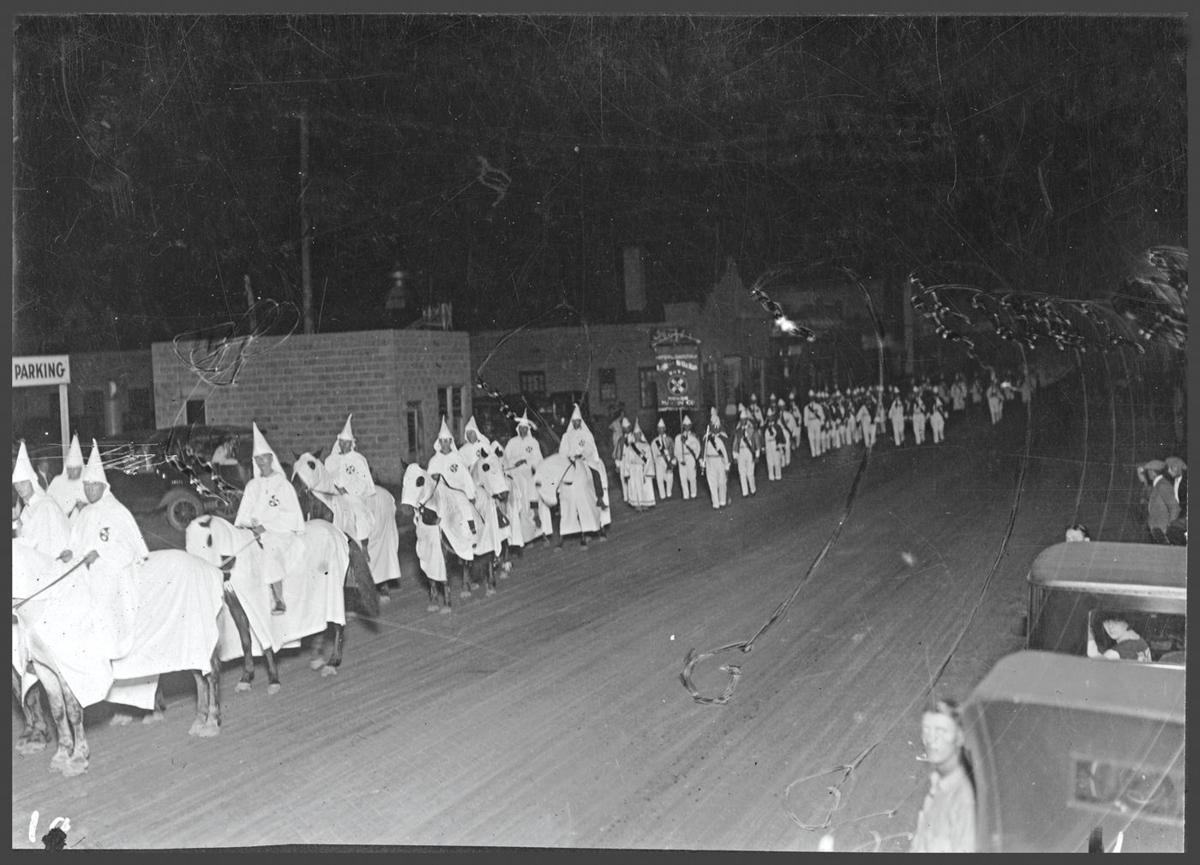

Ku Klux Klan members march through downtown Owatonna during one of their Konklaves in the 1920s. (Photo courtesy Minnesota Historical Society)

Klan members and their cars dressed up in full KKK regalia on the Steele County Fairgrounds during one of the group’s Konklaves of the 1920s. (Photo courtesy Minnesota Historical Society)

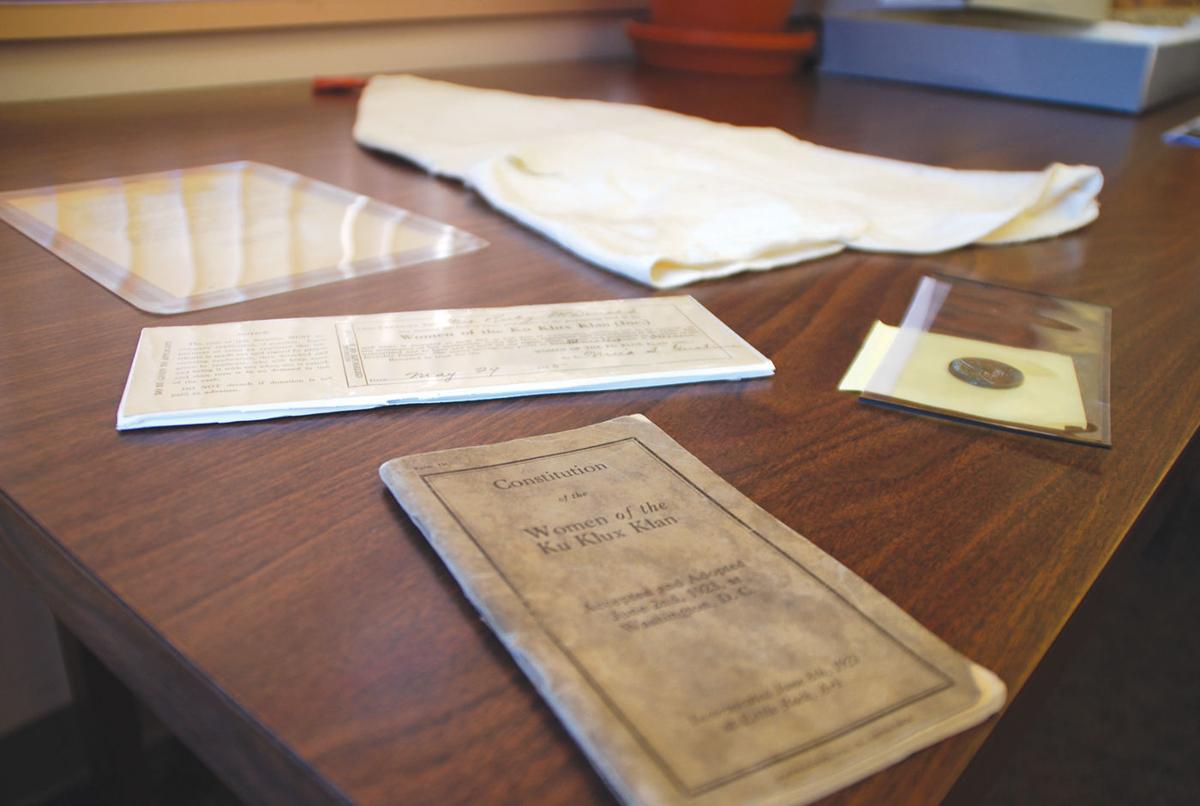

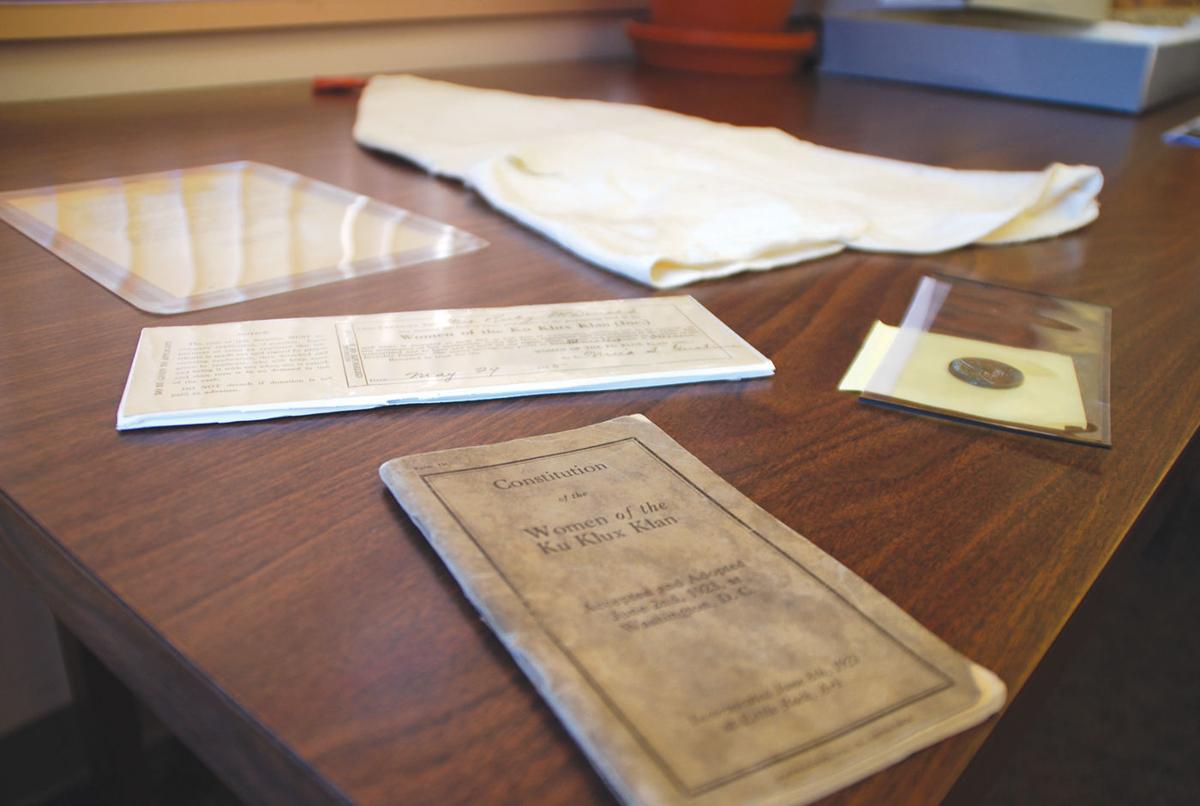

Coins, membership receipts, a “Constitution of the Women of the Ku Klux Klan” and a white hood are among the local KKK artifacts librarian Nancy Vaillancourt has gathered in more than 15 years of research into the history of the Klan in Steele County. (William Morris/People’s Press)

OWATONNA — Years ago, when a library patron asked Nancy Vaillancourt for information about the history of the Ku Klux Klan in Steele County, her supervisor at the time told her, “you won’t find much because they were a secret society.”

In a folder labeled “Ku Klux Klan” at the Steele County Historical Society, she found a solitary newspaper clipping, a meeting notice for a Klan group at an Ellendale church. But as she continued digging, she found that the Klan in Steele County wasn’t actually a secret at all.

“It’s uncomfortable,” said Vaillancourt, now Blooming Prairie branch librarian. “It’s uncomfortable to think maybe their ancestors, their family members were involved. I’ve had people ask me, ‘Have you found my family name yet?’”

In fact, as laid out in a 2010 Minnesota History Magazine article co-authored by Vaillancourt in 2010, the Klan had a robust presence in Steele County, and Minnesota as a whole, in the 1920s. Owatonna in particular was the site of several statewide KKK rallies that drew hundreds of white-hooded marchers through downtown and to rallies in Central Park and at the Steele County Fairgrounds. And as she watched the news last week of protests and marchers from the Ku Klux Klan in Charlottesville, Virginia, last week, Vaillancourt said she felt a sense of disbelief that such organizations as the Klan are trying to make a revival.

“People want to deny that it happened,” she said. “There are people who say, well that never happened here. I think we’ve proven that it has.”

Different Klan for different states

The wave of Klan activity that grew in Minnesota in the 1920s was part of a broader national revival for the organization, driven, Vaillancourt said, by social upheaval after World War I and the popular movie “The Birth of a Nation” in 1915. Although first reformed in Georgia, the Klan flourished especially in the west and Midwest. Relatively few instances of open violence in Minnesota are attributed to the Klan, although several perpetrators of the 1920 Duluth lynchings were later found on Klan rosters, but it was anything but secretive about its beliefs.

“The Klan had different faces in different parts of the country,” Vaillancourt said. “In the South, it was against blacks. In our area, where there weren’t as many blacks, it was against Jews, and especially, in our area, against Catholics.”

Owatonna at the time had three Catholic parishes, as well as St. Mary’s School, and there were several other parishes around the county. They were the primary local targets of the Klan.

“The rationalization was, the Klan was against Catholics because they were influenced by a foreign power, the Pope,” Vaillancourt said. “They were being 100 percent American, that was the motto they had, and the people who were Catholic weren’t, obviously, because they listened to someone who was a foreigner.”

In addition to public meetings and rallies, the Klan engaged in more direct forms of intimidation. Sisters Jean and Edith Zamboni, both 92 and lifelong members of St. Joseph’s Parish, were very young children when the Klan burned a cross down the block from their home on University Street, outside St. Mary’s School.

“I don’t really remember any of that, but our folks would have,” Jean Zamboni said. “I just remember people were afraid, and we had a neighbor that my mother wondered if he was part of that. Of course, we never asked him.”

It wasn’t just in Owatonna. In his 2003 book “Hamlet on the Straight River,” local historian John Gross records a 1923 newspaper article about a very public demonstration in Medford.

“The residents of this village were startled from their slumbers about eleven o’clock Monday evening by a terrific explosion and on rushing to windows or doors beheld a huge flaming cross on the hill east of town,” writes the Journal-Chronicle newspaper on Sept. 1, 1923. “From reports it seems that the cross was erected on the hill (east of school) and then a heavy charge of dynamite exploded nearby to attract attention to this spectacle.”

While the Klan didn’t directly claim credit for that incident, by the following year, they were openly taking part in civic life, with robed members making a dramatic entrance to a benefit event to present a $20 gold piece to help cover a resident’s medical expenses. On another memorable occasion, a Klan member in full regalia galloped through Medford on horseback bearing a flaming cross.

“My impression has always been it was more, I think, just something to do to gain attention,” Gross said. “I don’t think they were violent, in my mind, although they did burn a cross here in Medford. There was never anyone brutalized or whipped here to my knowledge. It was just more the symbolism.”

Vaillancourt’s 2010 article also cites Klan demonstrations in Bixby, Hope and Ellendale, but it was in Owatonna that the Klan attained its highest profile in the region.

Owatonna KonklavesThe first references to the Klan in Owatonna date to 1923, and in 1925, Owatonna was the site of the group’s second annual statewide Konklave. Delegations from all over the state arrived for music, games, speeches, a triple wedding, dinner served by the ladies of Trinity English Lutheran Church, and of course a parade. Organizers predicted 10,000 marchers, and while actual numbers fell well short of that, the Daily People’s Press counted a still-substantial 1,055 participants in the parade.

The Klan held another Konklave in Owatonna in 1926, this time on a tract of land the group purchased on the east side of town that became known and was recorded on city maps as Klan Park. A third Konklave was scheduled for 1927, but midway through, the city was hit by drenching rain, and the parade and evening activities were cancelled.

All of its events were drenched in patriotic and Christian symbolism, Vaillancourt said.

“A typical konklave would be a parade, often silent, walking down the street,” she said. “They often would have floats in it, and the most eerie for me is a woman sitting by a cross, and there are 4 Klan members around her with their swords drawn crossed over her, singing Onward Christian Soldiers.”

The Klan’s influence waned sharply in the latter years of the 1920s, as scandals around the country dirtied the snowy sheen of the Klan’s public image. Klan Park was sold in 1945 and today is slated to become a children’s soccer complex, and the “klavern” structure once built on it is no longer standing. The Holding Company of the Ku Klux Klan of Steele County remained on the books until it was dissolved in 1997 by the Minnesota Secretary of State for failure to register as a nonprofit by a 1990 deadline.

But for a time, the Klan was a dominant force in the region, and as she researched it, Vaillancourt met many families who had old Klan placards or medallions or hoods tucked away in forgotten boxes.

“I don’t think people were aware of how big it was, how many people were involved, and I think there was a hope that we can just forget about it, that that’s not how we want to be defined, as a place where the Klan was active,” she said. “In fact, it was people from outside the community coming and asking questions that kind of got me started doing research.”

And while the Klan, in its various modern manifestations, has no known footholds in the area, Vaillancourt said it’s important people acknowledge that the organization has a local history.

“The reason I’ve done the research is to show, it can happen here, it did happen here, and if we aren’t careful, it could happen again,” she said.

William Morris is a reporter for the Owatonna People’s Press.

https://www.southernminn.com/owatonna_peoples_press/news/article_326115e2-f0e2-545f-81ba-60887df37e7a.html

New book documents proliferation of second-wave Ku Klux Klan as political, social group in southern MN

By Amanda Dyslin adyslin@mankatofreepress.com

The Mankato Free Press

Nov 7, 2013

The Ku Klux Klan on parade in 1926 in Washington, D.C. A new book by author and historian Elizabeth Dorsey Hatle explores the KKK's history in Minnesota.

Wikimedia photo

The Mankato Free Press

Elizabeth Dorsey

The Mankato Free Press

"The Ku Klux Klan in Minnesota" was recently released by The History Press.

The Mankato Free Press

NOTE: This story appeared in the Nov. 3 edition of The Free Press, but was mistakenly not posted online.

The words Ku Klux Klan are synonymous with Civil War-era and Civil Rights-era racial hatred, violence and terrorism, especially in the South.

But those were the first and third waves, set 100 years apart in American history. The second wave was a nationwide movement, which took on the same white hooded costumes and lingo as the first, and there wasn’t a single county in Minnesota that didn’t have a presence.

In fact, St. James and Fairmont had two of the largest factions in the state, and both cities have KKK robes and numerous newspaper articles in their historical society collections to prove it.

Besides the sheer presence of the group this far north, author and historian Elizabeth Dorsey Hatle said the mission and purpose of the 1920s KKK also aren’t widely understood today. She herself learned a great deal while researching her recently released book, “The Ku Klux Klan in Minnesota,” published by The History Press.

“The second wave was more of a political movement,” said Hatle, a history teacher in Minneapolis. “In Minnesota, we just didn’t have many black people.”

![KKK book [Duplicate]](https://bloximages.chicago2.vip.townnews.com/mankatofreepress.com/content/tncms/assets/v3/editorial/2/63/26308be6-8a29-51ee-a428-ec77a94b0f1b/54059780a349a.image.jpg)

Who was the KKK?

The politically conservative Klan was opposed to unions, Catholics, immigrants and alcohol. They were pro-white and in favor of protesting the groundswell of change that the “roaring ‘20s” was bringing about.

The second wave is responsible for introducing cross burning as a symbol of intimidation and a representation of its pro-Christian message. Lighting one was often accompanied with prayers and hymns.

The Klan was also fairly successful during that era, she said. They had large membership numbers and were able to get members into political offices, such as on school boards and commissions.

“There was a lot of change that was going on in the 1920s with the automobile and people moving to the cities,” she said. “They wanted to keep the immigrant population down. They were very anti-Catholic and (opposed to people) who were seen as not being good American citizens.”

Area historical societies said, for the most part, the Klan gathered to socialize.

Wilma Wolner, director of the Watonwan County Historical Society, said the county’s KKK chapter seemed to have one main purpose: “partying.”

“They did burn a cross in St. James,” Wolner said. “(But mostly) it was a social club.”

The Midwest’s last KKK grand dragon was the mayor of St. James, Clyde E. McNaught. He was a World War I veteran, a Mason and a doctor in St. James who opened a 12-bed hospital. Tom Anderson, president of the Watonwan County Historical Society-St. James Chapter, said the local sheriff also was a KKK member.

Anderson said he started digging more into the county’s KKK history when a resident donated a white robe that had been in their family. (The regalia is on display at the Watonwan County Historical Society-St. James Chapter.) He said he too learned that the second wave was more politically and socially motivated, not violent.

“It was kind of a little bit different organization then,” he said. “It was more of a patriotic organization that kind of sprang out of World War I. … A lot of folks are going into this with a present-day attitude (about KKK violence and terrorism), and it really at the time probably wasn’t that.”

21,000 attend KKK event

The St. James chapter also was connected with Fairmont’s, which had a big delegation. In July 1926, 21,000 people attended a Klan celebration at Interlaken Park, which is about twice the size of the city’s current population.

The Fairmont Sentinel reported there wasn’t a single instance of disorderly conduct or trace of alcohol observed.

A passage in Hatle’s book states: “Also at the July weekend, there was a ‘living cross’ at the event composed of 250 robed Klansmen, each holding a red torch. The voices of several hundred Klanswomen, set aside from the crowd a quarter of a mile away, could be heard singing to the crowd in perfect pitch and harmony to their large audience.”

Mankato also had a KKK presence, with passages in the book indicating cross-burnings and Klan initiation ceremonies. Mankato Daily Free Press reports seemed supportive of the KKK presence, stating the group advocated the tenants of Christianity, white supremacy, protection of “pure womanhood” and the upholding of the Constitution of the United States, Hatle said.

Jessica Potter, executive director of the Blue Earth County Historical Society, said she has touched every artifact in the society’s collection, and there are no KKK photos or artifacts. When she first learned of the KKK presence here, she said she was surprised.

“You look them up today and you say, ‘They did what?’” Potter said, adding that, at the time, the group truly believed they were promoting what was right and just.

The broader context of the era shows there were actually numerous fraternal organizations, not just the KKK, Potter said. Just like the rest of the country, groups such as the Odd Fellows and numerous others were very popular during the 1920s era in southern Minnesota, brought about by Women’s Suffrage, urbanization, the “Jazz Age,” prohibition and other societal changes.

“Secret societies go back to before the turn of the century and long before that,” she said. “It’s just a different generation, and it’s how that generation thought they should act. … It’s a very different time, and it was a very active part of culture.”

Book began with Duluth memorial

Hatle’s interest in the KKK was piqued when she was writing an editorial in advance of the Clayton Jackson McGhie Memorial in Duluth, which was dedicated to the memory of three black men who were beaten, tortured and hanged in downtown Duluth for a crime they didn’t commit. In Hatle’s research of the June 15, 1920, event, she came across photographs of floats from Klan parades in Minnesota, and it led her down a rabbit hole.

She conducted a great deal of research at historical societies and in newspapers for an article for Minnesota History Magazine, and then numerous families began contacting her saying they had ancestors who were KKK members and offered their stories.

That’s when Hatle knew she had a book in the works.

“If newspapers put anything in (about the Klan), that usually meant they supported it,” Hatle said.

The KKK’s presence in Minnesota was predominately from 1920-1925, but it existed until about 1930, with the Great Depression putting a period on the second-wave movement.

“The Ku Klux Klan in Minnesota” can be purchased at historypress.net and amazon.com.

Aug 25, 2017

Ku Klux Klan members march through downtown Owatonna during one of their Konklaves in the 1920s. (Photo courtesy Minnesota Historical Society)

Klan members and their cars dressed up in full KKK regalia on the Steele County Fairgrounds during one of the group’s Konklaves of the 1920s. (Photo courtesy Minnesota Historical Society)

Coins, membership receipts, a “Constitution of the Women of the Ku Klux Klan” and a white hood are among the local KKK artifacts librarian Nancy Vaillancourt has gathered in more than 15 years of research into the history of the Klan in Steele County. (William Morris/People’s Press)

OWATONNA — Years ago, when a library patron asked Nancy Vaillancourt for information about the history of the Ku Klux Klan in Steele County, her supervisor at the time told her, “you won’t find much because they were a secret society.”

In a folder labeled “Ku Klux Klan” at the Steele County Historical Society, she found a solitary newspaper clipping, a meeting notice for a Klan group at an Ellendale church. But as she continued digging, she found that the Klan in Steele County wasn’t actually a secret at all.

“It’s uncomfortable,” said Vaillancourt, now Blooming Prairie branch librarian. “It’s uncomfortable to think maybe their ancestors, their family members were involved. I’ve had people ask me, ‘Have you found my family name yet?’”

In fact, as laid out in a 2010 Minnesota History Magazine article co-authored by Vaillancourt in 2010, the Klan had a robust presence in Steele County, and Minnesota as a whole, in the 1920s. Owatonna in particular was the site of several statewide KKK rallies that drew hundreds of white-hooded marchers through downtown and to rallies in Central Park and at the Steele County Fairgrounds. And as she watched the news last week of protests and marchers from the Ku Klux Klan in Charlottesville, Virginia, last week, Vaillancourt said she felt a sense of disbelief that such organizations as the Klan are trying to make a revival.

“People want to deny that it happened,” she said. “There are people who say, well that never happened here. I think we’ve proven that it has.”

Different Klan for different states

The wave of Klan activity that grew in Minnesota in the 1920s was part of a broader national revival for the organization, driven, Vaillancourt said, by social upheaval after World War I and the popular movie “The Birth of a Nation” in 1915. Although first reformed in Georgia, the Klan flourished especially in the west and Midwest. Relatively few instances of open violence in Minnesota are attributed to the Klan, although several perpetrators of the 1920 Duluth lynchings were later found on Klan rosters, but it was anything but secretive about its beliefs.

“The Klan had different faces in different parts of the country,” Vaillancourt said. “In the South, it was against blacks. In our area, where there weren’t as many blacks, it was against Jews, and especially, in our area, against Catholics.”

Owatonna at the time had three Catholic parishes, as well as St. Mary’s School, and there were several other parishes around the county. They were the primary local targets of the Klan.

“The rationalization was, the Klan was against Catholics because they were influenced by a foreign power, the Pope,” Vaillancourt said. “They were being 100 percent American, that was the motto they had, and the people who were Catholic weren’t, obviously, because they listened to someone who was a foreigner.”

In addition to public meetings and rallies, the Klan engaged in more direct forms of intimidation. Sisters Jean and Edith Zamboni, both 92 and lifelong members of St. Joseph’s Parish, were very young children when the Klan burned a cross down the block from their home on University Street, outside St. Mary’s School.

“I don’t really remember any of that, but our folks would have,” Jean Zamboni said. “I just remember people were afraid, and we had a neighbor that my mother wondered if he was part of that. Of course, we never asked him.”

It wasn’t just in Owatonna. In his 2003 book “Hamlet on the Straight River,” local historian John Gross records a 1923 newspaper article about a very public demonstration in Medford.

“The residents of this village were startled from their slumbers about eleven o’clock Monday evening by a terrific explosion and on rushing to windows or doors beheld a huge flaming cross on the hill east of town,” writes the Journal-Chronicle newspaper on Sept. 1, 1923. “From reports it seems that the cross was erected on the hill (east of school) and then a heavy charge of dynamite exploded nearby to attract attention to this spectacle.”

While the Klan didn’t directly claim credit for that incident, by the following year, they were openly taking part in civic life, with robed members making a dramatic entrance to a benefit event to present a $20 gold piece to help cover a resident’s medical expenses. On another memorable occasion, a Klan member in full regalia galloped through Medford on horseback bearing a flaming cross.

“My impression has always been it was more, I think, just something to do to gain attention,” Gross said. “I don’t think they were violent, in my mind, although they did burn a cross here in Medford. There was never anyone brutalized or whipped here to my knowledge. It was just more the symbolism.”

Vaillancourt’s 2010 article also cites Klan demonstrations in Bixby, Hope and Ellendale, but it was in Owatonna that the Klan attained its highest profile in the region.

Owatonna KonklavesThe first references to the Klan in Owatonna date to 1923, and in 1925, Owatonna was the site of the group’s second annual statewide Konklave. Delegations from all over the state arrived for music, games, speeches, a triple wedding, dinner served by the ladies of Trinity English Lutheran Church, and of course a parade. Organizers predicted 10,000 marchers, and while actual numbers fell well short of that, the Daily People’s Press counted a still-substantial 1,055 participants in the parade.

The Klan held another Konklave in Owatonna in 1926, this time on a tract of land the group purchased on the east side of town that became known and was recorded on city maps as Klan Park. A third Konklave was scheduled for 1927, but midway through, the city was hit by drenching rain, and the parade and evening activities were cancelled.

All of its events were drenched in patriotic and Christian symbolism, Vaillancourt said.

“A typical konklave would be a parade, often silent, walking down the street,” she said. “They often would have floats in it, and the most eerie for me is a woman sitting by a cross, and there are 4 Klan members around her with their swords drawn crossed over her, singing Onward Christian Soldiers.”

The Klan’s influence waned sharply in the latter years of the 1920s, as scandals around the country dirtied the snowy sheen of the Klan’s public image. Klan Park was sold in 1945 and today is slated to become a children’s soccer complex, and the “klavern” structure once built on it is no longer standing. The Holding Company of the Ku Klux Klan of Steele County remained on the books until it was dissolved in 1997 by the Minnesota Secretary of State for failure to register as a nonprofit by a 1990 deadline.

But for a time, the Klan was a dominant force in the region, and as she researched it, Vaillancourt met many families who had old Klan placards or medallions or hoods tucked away in forgotten boxes.

“I don’t think people were aware of how big it was, how many people were involved, and I think there was a hope that we can just forget about it, that that’s not how we want to be defined, as a place where the Klan was active,” she said. “In fact, it was people from outside the community coming and asking questions that kind of got me started doing research.”

And while the Klan, in its various modern manifestations, has no known footholds in the area, Vaillancourt said it’s important people acknowledge that the organization has a local history.

“The reason I’ve done the research is to show, it can happen here, it did happen here, and if we aren’t careful, it could happen again,” she said.

William Morris is a reporter for the Owatonna People’s Press.

https://www.southernminn.com/owatonna_peoples_press/news/article_326115e2-f0e2-545f-81ba-60887df37e7a.html

New book documents proliferation of second-wave Ku Klux Klan as political, social group in southern MN

By Amanda Dyslin adyslin@mankatofreepress.com

The Mankato Free Press

Nov 7, 2013

The Ku Klux Klan on parade in 1926 in Washington, D.C. A new book by author and historian Elizabeth Dorsey Hatle explores the KKK's history in Minnesota.

Wikimedia photo

The Mankato Free Press

Elizabeth Dorsey

The Mankato Free Press

"The Ku Klux Klan in Minnesota" was recently released by The History Press.

The Mankato Free Press

NOTE: This story appeared in the Nov. 3 edition of The Free Press, but was mistakenly not posted online.

The words Ku Klux Klan are synonymous with Civil War-era and Civil Rights-era racial hatred, violence and terrorism, especially in the South.

But those were the first and third waves, set 100 years apart in American history. The second wave was a nationwide movement, which took on the same white hooded costumes and lingo as the first, and there wasn’t a single county in Minnesota that didn’t have a presence.

In fact, St. James and Fairmont had two of the largest factions in the state, and both cities have KKK robes and numerous newspaper articles in their historical society collections to prove it.

Besides the sheer presence of the group this far north, author and historian Elizabeth Dorsey Hatle said the mission and purpose of the 1920s KKK also aren’t widely understood today. She herself learned a great deal while researching her recently released book, “The Ku Klux Klan in Minnesota,” published by The History Press.

“The second wave was more of a political movement,” said Hatle, a history teacher in Minneapolis. “In Minnesota, we just didn’t have many black people.”

![KKK book [Duplicate]](https://bloximages.chicago2.vip.townnews.com/mankatofreepress.com/content/tncms/assets/v3/editorial/2/63/26308be6-8a29-51ee-a428-ec77a94b0f1b/54059780a349a.image.jpg)

Who was the KKK?

The politically conservative Klan was opposed to unions, Catholics, immigrants and alcohol. They were pro-white and in favor of protesting the groundswell of change that the “roaring ‘20s” was bringing about.

The second wave is responsible for introducing cross burning as a symbol of intimidation and a representation of its pro-Christian message. Lighting one was often accompanied with prayers and hymns.

The Klan was also fairly successful during that era, she said. They had large membership numbers and were able to get members into political offices, such as on school boards and commissions.

“There was a lot of change that was going on in the 1920s with the automobile and people moving to the cities,” she said. “They wanted to keep the immigrant population down. They were very anti-Catholic and (opposed to people) who were seen as not being good American citizens.”

Area historical societies said, for the most part, the Klan gathered to socialize.

Wilma Wolner, director of the Watonwan County Historical Society, said the county’s KKK chapter seemed to have one main purpose: “partying.”

“They did burn a cross in St. James,” Wolner said. “(But mostly) it was a social club.”

The Midwest’s last KKK grand dragon was the mayor of St. James, Clyde E. McNaught. He was a World War I veteran, a Mason and a doctor in St. James who opened a 12-bed hospital. Tom Anderson, president of the Watonwan County Historical Society-St. James Chapter, said the local sheriff also was a KKK member.

Anderson said he started digging more into the county’s KKK history when a resident donated a white robe that had been in their family. (The regalia is on display at the Watonwan County Historical Society-St. James Chapter.) He said he too learned that the second wave was more politically and socially motivated, not violent.

“It was kind of a little bit different organization then,” he said. “It was more of a patriotic organization that kind of sprang out of World War I. … A lot of folks are going into this with a present-day attitude (about KKK violence and terrorism), and it really at the time probably wasn’t that.”

21,000 attend KKK event

The St. James chapter also was connected with Fairmont’s, which had a big delegation. In July 1926, 21,000 people attended a Klan celebration at Interlaken Park, which is about twice the size of the city’s current population.

The Fairmont Sentinel reported there wasn’t a single instance of disorderly conduct or trace of alcohol observed.

A passage in Hatle’s book states: “Also at the July weekend, there was a ‘living cross’ at the event composed of 250 robed Klansmen, each holding a red torch. The voices of several hundred Klanswomen, set aside from the crowd a quarter of a mile away, could be heard singing to the crowd in perfect pitch and harmony to their large audience.”

Mankato also had a KKK presence, with passages in the book indicating cross-burnings and Klan initiation ceremonies. Mankato Daily Free Press reports seemed supportive of the KKK presence, stating the group advocated the tenants of Christianity, white supremacy, protection of “pure womanhood” and the upholding of the Constitution of the United States, Hatle said.

Jessica Potter, executive director of the Blue Earth County Historical Society, said she has touched every artifact in the society’s collection, and there are no KKK photos or artifacts. When she first learned of the KKK presence here, she said she was surprised.

“You look them up today and you say, ‘They did what?’” Potter said, adding that, at the time, the group truly believed they were promoting what was right and just.

The broader context of the era shows there were actually numerous fraternal organizations, not just the KKK, Potter said. Just like the rest of the country, groups such as the Odd Fellows and numerous others were very popular during the 1920s era in southern Minnesota, brought about by Women’s Suffrage, urbanization, the “Jazz Age,” prohibition and other societal changes.

“Secret societies go back to before the turn of the century and long before that,” she said. “It’s just a different generation, and it’s how that generation thought they should act. … It’s a very different time, and it was a very active part of culture.”

Book began with Duluth memorial

Hatle’s interest in the KKK was piqued when she was writing an editorial in advance of the Clayton Jackson McGhie Memorial in Duluth, which was dedicated to the memory of three black men who were beaten, tortured and hanged in downtown Duluth for a crime they didn’t commit. In Hatle’s research of the June 15, 1920, event, she came across photographs of floats from Klan parades in Minnesota, and it led her down a rabbit hole.

She conducted a great deal of research at historical societies and in newspapers for an article for Minnesota History Magazine, and then numerous families began contacting her saying they had ancestors who were KKK members and offered their stories.

That’s when Hatle knew she had a book in the works.

“If newspapers put anything in (about the Klan), that usually meant they supported it,” Hatle said.

The KKK’s presence in Minnesota was predominately from 1920-1925, but it existed until about 1930, with the Great Depression putting a period on the second-wave movement.

“The Ku Klux Klan in Minnesota” can be purchased at historypress.net and amazon.com.

No comments:

Post a Comment