FROM THE ARCHIVE

Pandemics, Politics and the Spanish Flu

One of the worst plagues in human history is largely forgotten now.

For our own sakes, it’s time to remember what happened.

By Crawford Kilian| TheTyee.ca

2017

Tyee contributing editor Crawford Kilian blogs about the politics of public health on his blog H5N1.

Pale Rider: The Spanish Flu of 1918 and How It Changed the World

Laura Spinney

Jonathan Cape (2017)

“The Spanish flu,” Laura Spinney tells us, “infected one in three people on earth, or 500 million human beings. Between the first case recorded on 4 March 1918 and the last sometime in March 1920, it killed 50-100 million, or between 2.5 and 5 per cent of the global population — a range that reflects the uncertainty that still surrounds it. …It was the greatest tidal wave of death since the Black Death, perhaps in the whole of human history.”

Yet when it was over, a kind of stunned silence fell on the survivors. People might talk about the carnage of the First World War and the resulting revolutions, but not about the much greater slaughter they had personally witnessed in their own homes and workplaces. My own grandparents, who had small children in 1918 and ’19, never mentioned the flu pandemic.

Part of that silence is thanks to the human tendency to pay more attention to some deaths than to others. The 3,000 deaths in the 9/11 attack are trivial compared to the 64,000 drug-overdose deaths the U.S. suffered last year, or the 660,000 worldwide malaria deaths so far this year. The 9/11 deaths changed the world, while we shrug off far greater death tolls.

But the silence after the pandemic was also like many soldiers’ PTSD: the survivors didn’t much want to talk about an experience that seemed to have neither cause nor remedy.

Spinney, who is both a science writer and novelist, is far enough removed from the pandemic to gain perspective on it, and storyteller enough to condense a global disaster into a chain of vivid stories linked by lucid explanation. In the process, she evokes a world that seems both farther from us than a mere century, and also uncomfortably close.

The Tyee is supported by readers like you Join us and grow independent media in Canada

Nobody knew anything

Nobody knew anything in 1918. The germ theory of disease, a few decades old, was as controversial then as climate change is now. “Virus” was a medical buzzword for “something we can’t see in a microscope that must be causing this or that disease.”

Even the word “influenza” was a hand-me-down from the Middle Ages, when the diagnosis for many ailments was the “influence” of the stars. The 19th century had seen many outbreaks of a respiratory disease called influenza, including the “Russian flu” of 1890 that had killed a million people. Less fatal flu outbreaks occurred yearly, as they continue to do.

So a wave of flu in the spring of 1918 didn’t stir much alarm though it killed more people and those of a younger age than usual — especially in the armies still locked in trench warfare. So many soldiers fell ill that a major German offensive — intended to knock France and Britain out of the war before the U.S. arrived — failed. Even though French and British soldiers were sick as well, they had the advantage of defence. (The Americans, meanwhile, were dying aboard their troop ships en route to the front.)

Most histories of the Spanish flu focus on events in Europe and the U.S., but Spinney’s scope is world-wide. Here is where her book distinguishes itself — by detailed scrutiny of the response to the pandemic in places like Brazil, China and India. All were baffled by the disease and by its seeming randomness. In the gold mines of South Africa’s Rand district, for example, black miners lived under crowded, unsanitary conditions that encouraged pneumonia. They fell ill with the flu, but most recovered. A week later, the flu hit Kimberley’s diamond mines — and the death rate was 35 times that of the gold miners.

Culture played a crucial role. In Spain, a charismatic bishop in the city of Zamora drew crowds into the churches to offer prayers to St. Rocco, the patron saint of plague, making the spread of flu much easier. The authorities tried to forbid mass gatherings; the bishop said they were interfering in church affairs.

Elsewhere, politics promoted the flu. In the Philippines, the Americans who’d occupied the islands 20 years before didn’t try to protect the local population except for a camp where Filipinos were training to join the U.S. war effort. Flu killed an estimated 80,000 Filipinos.

But the flu also promoted politics. After the Russian Revolution and civil war, Lenin brought in the first modern public healthcare system (at least for urban Russians). He asked doctors to make epidemic and famine prevention their top priority because flu and famine had nearly wiped out the Russian working classes.

Before that, however, flu had influenced not only the war but also the peace conference that followed. Woodrow Wilson almost certainly contracted Spanish flu en route to the Paris peace conference in 1919, and like many other cases, he suffered cognitive harm. His illness may also have helped cause the stroke he suffered a few months later; it left him crippled and unable to persuade Congress and the Senate to back the League of Nations.

In India, Mohandas Gandhi contracted flu. Already a leading figure in the struggle against British rule, Gandhi was temporarily unable to act as the epidemic aggravated a drought-related famine. But some of his followers began to build a grassroots organization to provide influenza relief — laying the groundwork for future liberation campaigns.

When Gandhi did recover, he was still too weak to control the response to a British bill that continued the rule of martial law in India after the end of the war. That bill, says Spinney, led to the Amritsar Massacre in April 1919, when brigadier general Reginald Dyer ordered his soldiers to fire into an unarmed crowd of protesters. Somewhere between 400 and 1,000 died. The slaughter was the beginning of the end of the British Raj.

The silence of the artists

If culture influenced influenza, influenza also influenced culture. Spinney explores the eerie silence about the pandemic in the work of 1920s writers. She argues that flu led to a general melancholy among artists, rather than works dramatizing its impact on individuals and communities.

From this she makes an interesting further case: We remember wars and then gradually forget them, while we forget pandemics and then gradually remember them. So, 72 years after the end of the Second World War, we contend with neo-Nazis while we also begin to sense what a shattering event the 1918-19 influenza pandemic really was.

A century later, we are far better equipped to deal with the next flu pandemic but also more vulnerable to it. The 2009-10 “swine flu” pandemic travelled at the speed of modern air travel; British schoolgirls brought it home from a holiday trip to Mexico. It killed over 200,000, a number too small to earn respect. In B.C., we had more than 1,000 cases and a mere 56 deaths — and promptly forgot them all.

The next influenza — whether H5N1, H7N9, or some other strain — could kill a magnitude more. As Santayana famously observed, “Those who do not remember the past are condemned to repeat it.” If we can’t reconstruct our memories of the Spanish flu quickly enough, millions more will die in the next pandemic. ![[Tyee]](https://thetyee.ca/ui/img/ico_fishie.png)

How Bad Can a Flu Be?

Lethal to thousands is the answer. B.C.’s last pandemic proved that fear and denial are grave public health hazards

By Crawford Kilian 23 Feb 2004 | TheTyee.ca

Crawford Kilian was born in New York City in 1941. He was raised in Los Angeles and Mexico City, and was educated at Columbia University (BA ’62) and Simon Fraser University (MA ’72). He served in the US Army from 1963 to 1965, and moved to Vancouver in 1967. He became a naturalized Canadian in 1973.

Crawford has published 21 books -- both fiction and non-fiction, and has written hundreds of articles. He taught at Vancouver City College in the late 1960s and was a professor at Capilano College from 1968 to 2008. Much of Crawford’s writing for The Tyee deals with education issues in British Columbia, but he is also interested in books, online media, and environmental issues.

Reporting Beat: Education, health, and books

Crawford’s Connection to BC: Though he was born in New York City, one of Crawford’s favourite places is Sointula, a small town off the northeast coast of Vancouver Island.

October 5, 2004: Vancouver reports its first case of New Flu, already labeled a pandemic by the World Health Organization. The virus has moved around the world with frightening speed from Europe, where it was first identified just a few weeks earlier.

October 11: Three hundred cases of New Flu have been confirmed in Vancouver.

October 20: Vancouver has three thousand cases of New Flu, one thousand reported in the past 24 hours. The pandemic has swamped the city’s health system.

This is the spike of the first wave. By the end of the year Vancouver’s total cases number about 28,000 and 3,700 of them have been fatal. Two smaller waves hit, one in mid-January 2005 and the last in February and March. By mid-2005, New Flu has vanished. Vancouver’s total cases have numbered 170,000; 5,000 have died.

Vancouver is not alone. A quarter of the province’s 4,000,000 people have fallen ill, and 37,000 are dead. Most of the deaths are among those aged 20 to 40. BC First Nations fatalities total almost 10,000, including many children and elderly. Nine and half million Canadians have suffered New Flu, and 285,000 are dead.

The Tyee is supported by readers like you Join us and grow independent media in Canada

This science-fiction scenario assumes only that New Flu is just as deadly as Spanish flu was between October 1918 and March 1919; I have simply scaled up the numbers to reflect our much larger population. In 1918, for example, an estimated 30,000 of Vancouver’s 100,000 residents caught the flu, and 900 died. Of the 4,000 province-wide deaths in 1918-19, over 1,000 were of First Nations. The city now holds almost 600,000; we could therefore expect a sixfold increase in cases and fatalities.

According to the new Canadian Pandemic Influenza Plan, a flu pandemic could kill between 11,000 and 58,000 Canadians while making 2.1 million to 5 million ill. No doubt we could fight flu more effectively than our great-grandparents did. But it’s instructive to see how they coped 85 years ago.

A forgotten disaster

Surprisingly, very little has been written about the impact of the Spanish flu in B.C. Local historian Margaret Andrews published an account of Vancouver’s response in BC Studies in 1977. In 1999, also in BC Studies, Mary-Ellen Klem described the devastation inflicted by the flu on BC’s First Nations. Elsewhere it receives only passing mention, a mere footnote to the end of the war. It was almost as if the experience had been blanked from our collective memory.

Vancouver had seen it coming. The first flu cases had appeared in Europe in June 1918, and returning soldiers that summer and fall had carried it to towns and cities across the country. Like other Canadian communities, Vancouver couldn’t cope.

Many doctors and nurses were still serving in Europe, and only about 200 nurses were available in Vancouver. Almost half of them were unavailable for duty when the second wave of flu hit in January 1919; they were either ill themselves or caring for their own families. Vancouver’s patient-doctor ratio was the highest it had been in a decade-680 to 1. The city’s Medical Health Officer, Dr. Frederick Underhill, had to find the resources both to limit the spread of the disease and to treat those who fell ill.

Prevention amounted to basic hygiene: avoiding crowds, covering coughs, plenty of fresh air. The city government, however, wanted more drastic steps. “Town closure” meant a ban on public gatherings, and the shutting down of schools, churches, and recreational facilities. Many flu-stricken North American cities had shut themselves down in this way, but Underhill didn’t see the point. Closing schools would only put kids out on the street, exposed to infection without even a careful teacher’s observation of possible symptoms

As well, Underhill pointed out, no one was ready to shut down business and industry. People would still be exposed to infection. (He was vindicated by the SARS outbreak in Singapore last year. Freed from school, kids wandered cheerfully through the downtown crowds of workers and shoppers.)

Vancouver shuts down

But within 10 days of the first flu case, political pressure forced the closure of Vancouver schools-which in any case were half-empty thanks to parental fear. A few days later, Underhill called for banning all public assemblies except in factories, stores and businesses.

The health-care system was also facing patients from outside the city, including many being brought in from smaller communities and even logging camps. Vancouver’s hospitals (St. Paul’s and Vancouver General) couldn’t handle all the cases, so closed schools became impromptu wards. King Edward School, next to VGH at 12th and Oak, was equipped to handle a thousand cases, staffed by school-board doctors and nurses. Strathcona School, on the east side, became a hospital for the Japanese community.

By the time the second wave hit, town closure was over, schools were open again, and authorities had to find new facilities. A 150-bed temporary hospital was built on the grounds of VGH.

Meanwhile, Andrews notes, it was business as usual. Car dealers were urging Vancouverites to buy their own “comfy and speedy Ford Car” rather than risk infection on crowded streetcars. Companies cranked out flu masks and veils, and druggists raised the price of camphor from 40 cents a pound to $6.50 in one week.

In an unlikely alliance, union members in the Metal Trades Council and Boiler Makers’ Union joined with the Employers’ Association to help create a central organization to fight the flu. Class conflict soon returned, however, with the Civic Employees’ Union threatening to strike. Since they represented employees in the water works, hospitals, health department, and cemetery, they got most of what they demanded.

Fear and denial

Meanwhile, the public ignored bans on public gatherings. The same parents who kept their kids out of school would then drag them to Victory Loan rallies, or to welcome the troops returning home. Vancouver even enjoyed two wild Armistice Nights: a false alarm on November 7, and the real thing four days later, with huge crowds celebrating in the streets. But movie attendance dropped, newspapers were smaller, and many offices were closed.

If Vancouver was good at ignoring its own pandemic, it was even better at ignoring the catastrophe afflicting BC’s First Nations. Mary-Ellen Klem’s article describes a disaster far worse than that afflicting white and Asian Canadians. Whole villages were infected; whole families were struck at once, with the living unable even to get up to bury their dead.

Klem says the BC native death rate from flu was nine times higher than for non-natives. While non-natives tended to die in their 20s and 30s, First Nations young people and elders were among the flu’s victims. This seems at least partly the result of widespread TB and other respiratory diseases, often contracted in residential schools. In 1907, a study had shown that 70 percent of young people who had graduated from such schools on the Prairies were dead within 15 years, mostly from TB.

The First Nations also felt betrayed by their white administrators, who had discouraged their former culture and assured them that life would be much better if only they would live like whites. In the event, even the white doctors assigned to First Nations reserves did little or nothing to ease the suffering.

Public health advances

A pandemic now would, we can hope, inflict much less damage on B.C. As with SARS, we could isolate early cases, master the virus’s genome, and perhaps find a vaccine within a few months. Sanitation would reduce the rate of transmission. Medical technology would save people who in 1918 would have been beyond help.

Yet we could still succumb to panic and denial, especially with modern media playing to our fears. Class and ethnic divisions could appear, just as SARS triggered some irrational avoidance of Chinese persons and businesses. Our health-care system, already stretched as it is, might not respond as powerfully as it would need to-especially when it still had to care for large numbers of regular patients.

The new Influenza Pandemic Plan is clearly a step in the right direction. But the next pandemic could well test our character far more harshly than our medical resources.

Crawford Kilian teaches at Capilano College and writes regularly for The Tyee. Among his books is Go Do Some Great Thing: The Black Pioneers of British Columbia (Douglas & McIntyre, 1978).

Lethal to thousands is the answer. B.C.’s last pandemic proved that fear and denial are grave public health hazards

By Crawford Kilian 23 Feb 2004 | TheTyee.ca

Crawford Kilian was born in New York City in 1941. He was raised in Los Angeles and Mexico City, and was educated at Columbia University (BA ’62) and Simon Fraser University (MA ’72). He served in the US Army from 1963 to 1965, and moved to Vancouver in 1967. He became a naturalized Canadian in 1973.

Crawford has published 21 books -- both fiction and non-fiction, and has written hundreds of articles. He taught at Vancouver City College in the late 1960s and was a professor at Capilano College from 1968 to 2008. Much of Crawford’s writing for The Tyee deals with education issues in British Columbia, but he is also interested in books, online media, and environmental issues.

Reporting Beat: Education, health, and books

Crawford’s Connection to BC: Though he was born in New York City, one of Crawford’s favourite places is Sointula, a small town off the northeast coast of Vancouver Island.

October 5, 2004: Vancouver reports its first case of New Flu, already labeled a pandemic by the World Health Organization. The virus has moved around the world with frightening speed from Europe, where it was first identified just a few weeks earlier.

October 11: Three hundred cases of New Flu have been confirmed in Vancouver.

October 20: Vancouver has three thousand cases of New Flu, one thousand reported in the past 24 hours. The pandemic has swamped the city’s health system.

This is the spike of the first wave. By the end of the year Vancouver’s total cases number about 28,000 and 3,700 of them have been fatal. Two smaller waves hit, one in mid-January 2005 and the last in February and March. By mid-2005, New Flu has vanished. Vancouver’s total cases have numbered 170,000; 5,000 have died.

Vancouver is not alone. A quarter of the province’s 4,000,000 people have fallen ill, and 37,000 are dead. Most of the deaths are among those aged 20 to 40. BC First Nations fatalities total almost 10,000, including many children and elderly. Nine and half million Canadians have suffered New Flu, and 285,000 are dead.

The Tyee is supported by readers like you Join us and grow independent media in Canada

This science-fiction scenario assumes only that New Flu is just as deadly as Spanish flu was between October 1918 and March 1919; I have simply scaled up the numbers to reflect our much larger population. In 1918, for example, an estimated 30,000 of Vancouver’s 100,000 residents caught the flu, and 900 died. Of the 4,000 province-wide deaths in 1918-19, over 1,000 were of First Nations. The city now holds almost 600,000; we could therefore expect a sixfold increase in cases and fatalities.

According to the new Canadian Pandemic Influenza Plan, a flu pandemic could kill between 11,000 and 58,000 Canadians while making 2.1 million to 5 million ill. No doubt we could fight flu more effectively than our great-grandparents did. But it’s instructive to see how they coped 85 years ago.

A forgotten disaster

Surprisingly, very little has been written about the impact of the Spanish flu in B.C. Local historian Margaret Andrews published an account of Vancouver’s response in BC Studies in 1977. In 1999, also in BC Studies, Mary-Ellen Klem described the devastation inflicted by the flu on BC’s First Nations. Elsewhere it receives only passing mention, a mere footnote to the end of the war. It was almost as if the experience had been blanked from our collective memory.

Vancouver had seen it coming. The first flu cases had appeared in Europe in June 1918, and returning soldiers that summer and fall had carried it to towns and cities across the country. Like other Canadian communities, Vancouver couldn’t cope.

Many doctors and nurses were still serving in Europe, and only about 200 nurses were available in Vancouver. Almost half of them were unavailable for duty when the second wave of flu hit in January 1919; they were either ill themselves or caring for their own families. Vancouver’s patient-doctor ratio was the highest it had been in a decade-680 to 1. The city’s Medical Health Officer, Dr. Frederick Underhill, had to find the resources both to limit the spread of the disease and to treat those who fell ill.

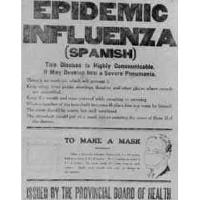

Prevention amounted to basic hygiene: avoiding crowds, covering coughs, plenty of fresh air. The city government, however, wanted more drastic steps. “Town closure” meant a ban on public gatherings, and the shutting down of schools, churches, and recreational facilities. Many flu-stricken North American cities had shut themselves down in this way, but Underhill didn’t see the point. Closing schools would only put kids out on the street, exposed to infection without even a careful teacher’s observation of possible symptoms

As well, Underhill pointed out, no one was ready to shut down business and industry. People would still be exposed to infection. (He was vindicated by the SARS outbreak in Singapore last year. Freed from school, kids wandered cheerfully through the downtown crowds of workers and shoppers.)

Vancouver shuts down

But within 10 days of the first flu case, political pressure forced the closure of Vancouver schools-which in any case were half-empty thanks to parental fear. A few days later, Underhill called for banning all public assemblies except in factories, stores and businesses.

The health-care system was also facing patients from outside the city, including many being brought in from smaller communities and even logging camps. Vancouver’s hospitals (St. Paul’s and Vancouver General) couldn’t handle all the cases, so closed schools became impromptu wards. King Edward School, next to VGH at 12th and Oak, was equipped to handle a thousand cases, staffed by school-board doctors and nurses. Strathcona School, on the east side, became a hospital for the Japanese community.

By the time the second wave hit, town closure was over, schools were open again, and authorities had to find new facilities. A 150-bed temporary hospital was built on the grounds of VGH.

Meanwhile, Andrews notes, it was business as usual. Car dealers were urging Vancouverites to buy their own “comfy and speedy Ford Car” rather than risk infection on crowded streetcars. Companies cranked out flu masks and veils, and druggists raised the price of camphor from 40 cents a pound to $6.50 in one week.

In an unlikely alliance, union members in the Metal Trades Council and Boiler Makers’ Union joined with the Employers’ Association to help create a central organization to fight the flu. Class conflict soon returned, however, with the Civic Employees’ Union threatening to strike. Since they represented employees in the water works, hospitals, health department, and cemetery, they got most of what they demanded.

Fear and denial

Meanwhile, the public ignored bans on public gatherings. The same parents who kept their kids out of school would then drag them to Victory Loan rallies, or to welcome the troops returning home. Vancouver even enjoyed two wild Armistice Nights: a false alarm on November 7, and the real thing four days later, with huge crowds celebrating in the streets. But movie attendance dropped, newspapers were smaller, and many offices were closed.

If Vancouver was good at ignoring its own pandemic, it was even better at ignoring the catastrophe afflicting BC’s First Nations. Mary-Ellen Klem’s article describes a disaster far worse than that afflicting white and Asian Canadians. Whole villages were infected; whole families were struck at once, with the living unable even to get up to bury their dead.

Klem says the BC native death rate from flu was nine times higher than for non-natives. While non-natives tended to die in their 20s and 30s, First Nations young people and elders were among the flu’s victims. This seems at least partly the result of widespread TB and other respiratory diseases, often contracted in residential schools. In 1907, a study had shown that 70 percent of young people who had graduated from such schools on the Prairies were dead within 15 years, mostly from TB.

The First Nations also felt betrayed by their white administrators, who had discouraged their former culture and assured them that life would be much better if only they would live like whites. In the event, even the white doctors assigned to First Nations reserves did little or nothing to ease the suffering.

Public health advances

A pandemic now would, we can hope, inflict much less damage on B.C. As with SARS, we could isolate early cases, master the virus’s genome, and perhaps find a vaccine within a few months. Sanitation would reduce the rate of transmission. Medical technology would save people who in 1918 would have been beyond help.

Yet we could still succumb to panic and denial, especially with modern media playing to our fears. Class and ethnic divisions could appear, just as SARS triggered some irrational avoidance of Chinese persons and businesses. Our health-care system, already stretched as it is, might not respond as powerfully as it would need to-especially when it still had to care for large numbers of regular patients.

The new Influenza Pandemic Plan is clearly a step in the right direction. But the next pandemic could well test our character far more harshly than our medical resources.

Crawford Kilian teaches at Capilano College and writes regularly for The Tyee. Among his books is Go Do Some Great Thing: The Black Pioneers of British Columbia (Douglas & McIntyre, 1978).

No comments:

Post a Comment