HISTORY DEC 17 2019 BORIS EGOROV

During the Moscow plague, dogs and pigs devoured corpses lying in the street. They even preyed on passers-by, ripping them to shreds.

1. Plague (1654-1655)

Global Look Press

The plague spread to the capital of the Russian state from either Persia or Crimea. According to contemporary accounts, it came “like a flame driven by the wind.” In the summer of 1654, when the body count began to number in the thousands, the tsar’s court, the boyars, and all wealthy townspeople fled the city. By moving to Moscow’s suburbs and other cities, they in fact helped spread the infection throughout the land.

The mad stampede of Streltsy officers and prison guards plunged the city into chaos, looting, and banditry. “The once crowded streets became deserted ... dogs and pigs devoured the dead and went wild, so no one dared to venture out alone for fear of being gnawed to death,” wrote Patriarch Macarius III of Antioch, who was then in the Russian state.

In the end, the authorities had no choice but to fight the epidemic. Quarantines were established in the infected areas, which were surrounded by outposts and blocked off by soldiers. The houses and homesteads of those killed by the plague were ruthlessly burned down. The smoke of burning wormwood and juniper was used to fumigate objects and clothing. Troops restored order to the capital.

By the fall of 1654, the epidemic had been largely contained. The plague did not penetrate westwards, where the army of Tsar Alexei Mikhailovich was laying siege to the then Polish-Lithuanian city of Smolensk; the northern territories (Novgorod and Pskov) remained untouched.

Although January of the following year saw some further outbreaks, the scale was nothing like as bad, and Moscow was not affected. The exact number of victims of the epidemic will never be known for sure, but researchers put the figure at between 25,000 and 700,000. It is believed that more than 85% of the population of Moscow perished.

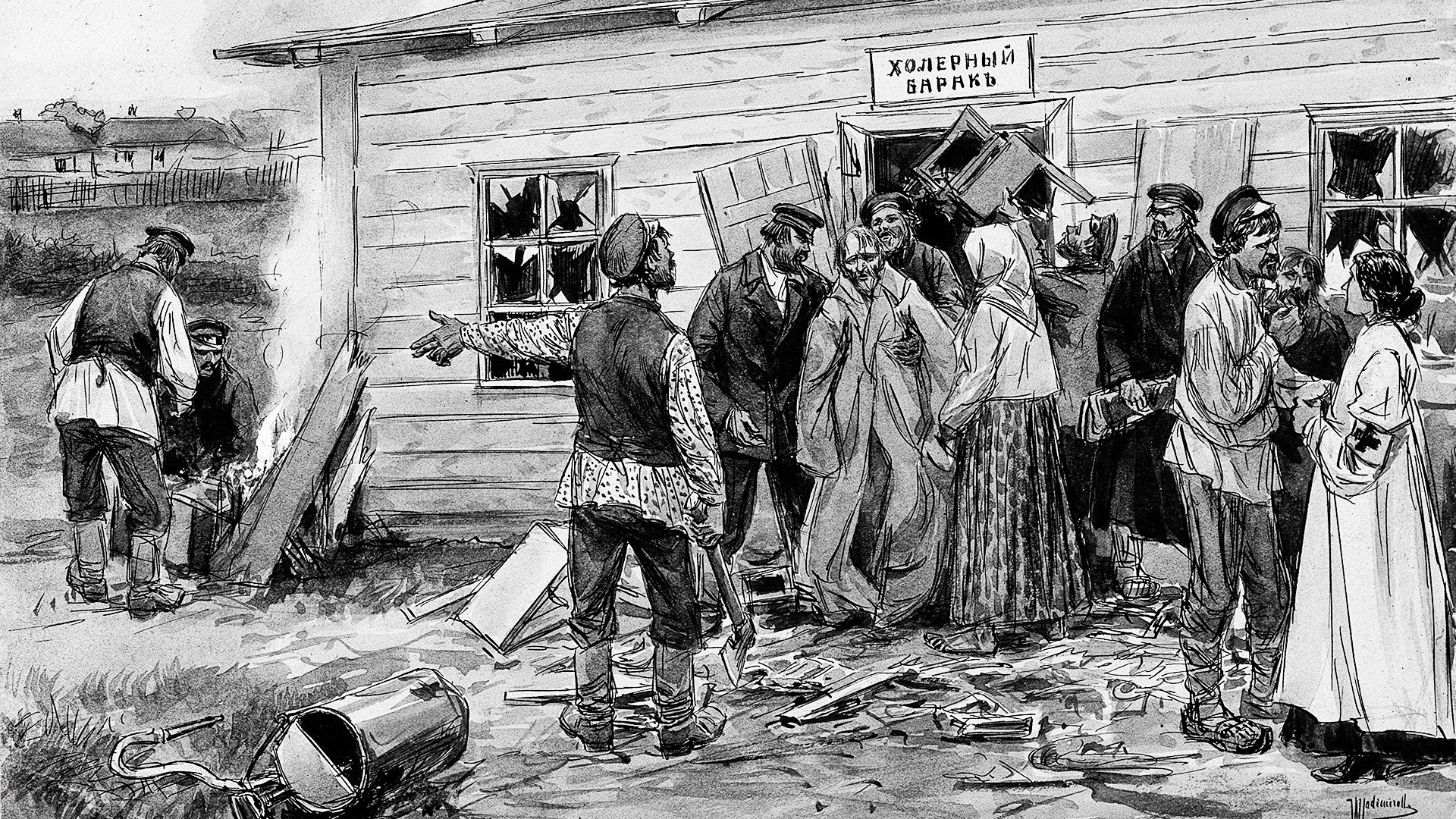

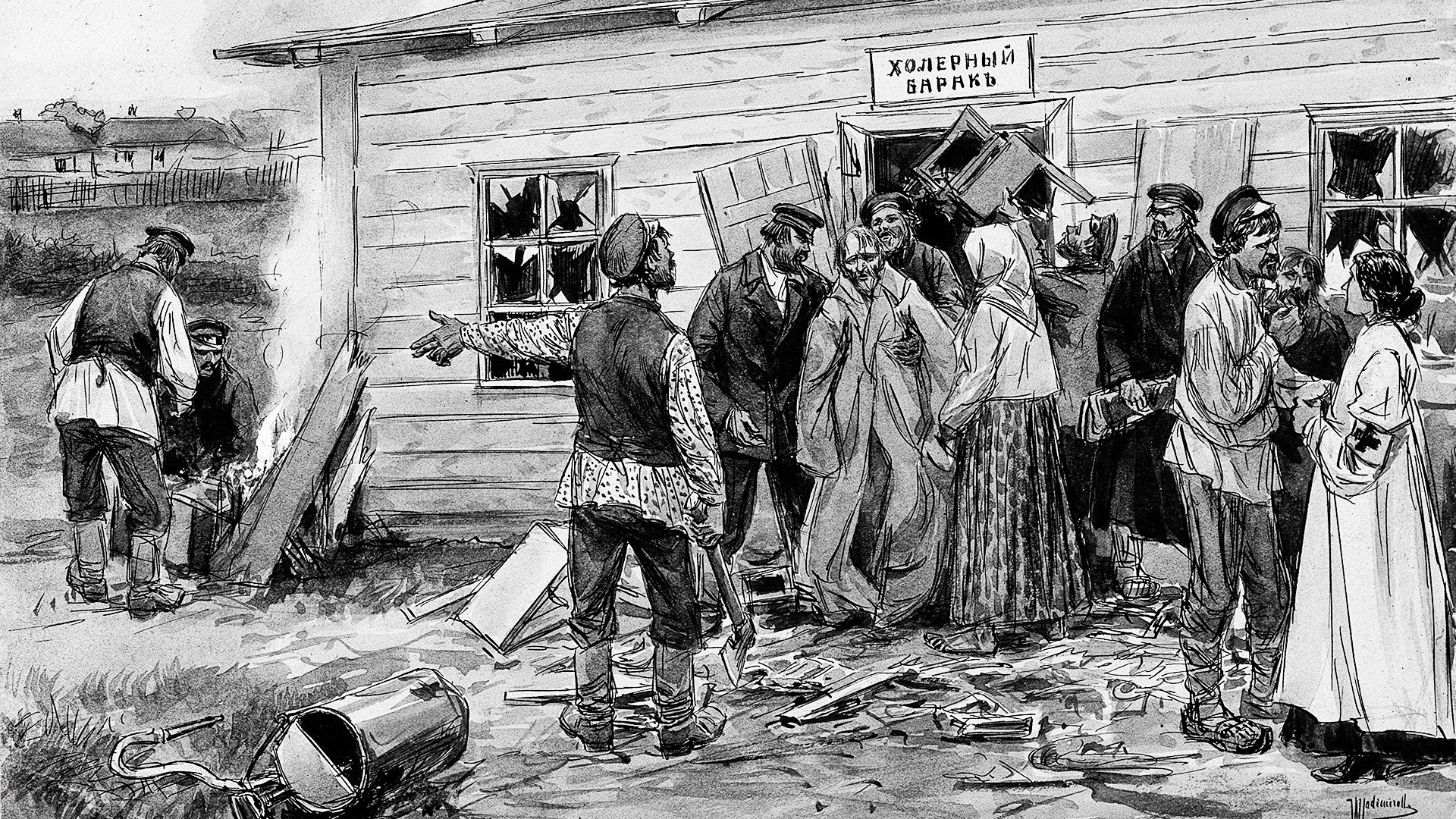

2. Cholera (1830-1831)

Getty Images

The deadliest disease of the 19th century first raised its ugly head in the southern regions of the Russian Empire in the 1820s, but only ten years later did it reveal its full destructive force.

In 1830, the epidemic — which had already devastated Georgia and the Volga region and would ultimately claim 200,000 lives in Russia — was viewed nonchalantly from afar in Moscow. Muscovites believed that their more northerly climate would protect them from misfortune.

“We’ll drive it away it with smoke, and take advice from doctors,” wrote the magazine Moscow Telegraph: “The best cure is a bold, lively spirit, carefulness not timidity, precaution not fearfulness.”

However, in the fall, the cheerful mood gave way to horror. As the number of victims climbed exponentially, the authorities closed universities and public places, banned all forms of public entertainment, and set up quarantine zones everywhere.

The early winter that year prevented the epidemic from entering the capital, but in April 1831 the first outbreaks of the disease were recorded in St. Petersburg, and in summer it spread like wildfire.

“This hellish malady is rampant,” wrote Alexander Nikitenko, a resident of the city on the Neva: “Go outside and you’ll see dozens of coffins on the way to the cemetery... It’s like the apocalypse has arrived, people wander among the coffins as if condemned to death, not knowing if their death knell has already sounded.”

General discontent with the quarantines and cordons (which badly affected trade) led to the so-called “cholera riots” that swept through the cities of the Russian Empire. Moreover, the Polish uprising was in full swing, giving rise to anti-Polish sentiment in society. It was rumored that Poles went around poisoning kitchen gardens and wells by night. Many innocent victims were lynched in the street by angry mobs.

3. Spanish flu (1918-1919)

Getty Images

The Spanish flu pandemic that followed WWI killed up to 100 million people worldwide (about 5% of the global population), making it one of the worst outbreaks in history. Nor did it spare post-revolutionary Russia.

Having penetrated the civil war-torn country in August 1918, the Spanish flu swept through Belarus and Ukraine, hitting Kiev especially hard, and onwards to Moscow and Petrograd, where one in two residents fell ill.

A nationwide catastrophe, the Spanish flu buried up to 2.7 million people in the space of just 18 months, which amounted to 3% of the country’s total population.

In Odessa, one victim was the silent movie star Vera Kholodnaya. The pandemic made no exception for the country’s new leadership either. In March 1919, Yakov Sverdlov, the “black devil of the Bolsheviks,” succumbed to the fatal contagion.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

1. Plague (1654-1655)

Global Look Press

The plague spread to the capital of the Russian state from either Persia or Crimea. According to contemporary accounts, it came “like a flame driven by the wind.” In the summer of 1654, when the body count began to number in the thousands, the tsar’s court, the boyars, and all wealthy townspeople fled the city. By moving to Moscow’s suburbs and other cities, they in fact helped spread the infection throughout the land.

The mad stampede of Streltsy officers and prison guards plunged the city into chaos, looting, and banditry. “The once crowded streets became deserted ... dogs and pigs devoured the dead and went wild, so no one dared to venture out alone for fear of being gnawed to death,” wrote Patriarch Macarius III of Antioch, who was then in the Russian state.

In the end, the authorities had no choice but to fight the epidemic. Quarantines were established in the infected areas, which were surrounded by outposts and blocked off by soldiers. The houses and homesteads of those killed by the plague were ruthlessly burned down. The smoke of burning wormwood and juniper was used to fumigate objects and clothing. Troops restored order to the capital.

By the fall of 1654, the epidemic had been largely contained. The plague did not penetrate westwards, where the army of Tsar Alexei Mikhailovich was laying siege to the then Polish-Lithuanian city of Smolensk; the northern territories (Novgorod and Pskov) remained untouched.

Although January of the following year saw some further outbreaks, the scale was nothing like as bad, and Moscow was not affected. The exact number of victims of the epidemic will never be known for sure, but researchers put the figure at between 25,000 and 700,000. It is believed that more than 85% of the population of Moscow perished.

2. Cholera (1830-1831)

Getty Images

The deadliest disease of the 19th century first raised its ugly head in the southern regions of the Russian Empire in the 1820s, but only ten years later did it reveal its full destructive force.

In 1830, the epidemic — which had already devastated Georgia and the Volga region and would ultimately claim 200,000 lives in Russia — was viewed nonchalantly from afar in Moscow. Muscovites believed that their more northerly climate would protect them from misfortune.

“We’ll drive it away it with smoke, and take advice from doctors,” wrote the magazine Moscow Telegraph: “The best cure is a bold, lively spirit, carefulness not timidity, precaution not fearfulness.”

However, in the fall, the cheerful mood gave way to horror. As the number of victims climbed exponentially, the authorities closed universities and public places, banned all forms of public entertainment, and set up quarantine zones everywhere.

The early winter that year prevented the epidemic from entering the capital, but in April 1831 the first outbreaks of the disease were recorded in St. Petersburg, and in summer it spread like wildfire.

“This hellish malady is rampant,” wrote Alexander Nikitenko, a resident of the city on the Neva: “Go outside and you’ll see dozens of coffins on the way to the cemetery... It’s like the apocalypse has arrived, people wander among the coffins as if condemned to death, not knowing if their death knell has already sounded.”

General discontent with the quarantines and cordons (which badly affected trade) led to the so-called “cholera riots” that swept through the cities of the Russian Empire. Moreover, the Polish uprising was in full swing, giving rise to anti-Polish sentiment in society. It was rumored that Poles went around poisoning kitchen gardens and wells by night. Many innocent victims were lynched in the street by angry mobs.

3. Spanish flu (1918-1919)

Getty Images

The Spanish flu pandemic that followed WWI killed up to 100 million people worldwide (about 5% of the global population), making it one of the worst outbreaks in history. Nor did it spare post-revolutionary Russia.

Having penetrated the civil war-torn country in August 1918, the Spanish flu swept through Belarus and Ukraine, hitting Kiev especially hard, and onwards to Moscow and Petrograd, where one in two residents fell ill.

A nationwide catastrophe, the Spanish flu buried up to 2.7 million people in the space of just 18 months, which amounted to 3% of the country’s total population.

In Odessa, one victim was the silent movie star Vera Kholodnaya. The pandemic made no exception for the country’s new leadership either. In March 1919, Yakov Sverdlov, the “black devil of the Bolsheviks,” succumbed to the fatal contagion.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

No comments:

Post a Comment