Viral Biopolitics

COVID-19 and the Living Dead

By Rachel Nelson

Field Notes

“As soon as power gave itself the function of administering life, its reason for being and the logic of its exercise—and not the awakening of humanitarian feelings—made it more difficult to apply the death penalty. How could power exercise its highest prerogatives by putting people to death, when its main role was to ensure, sustain, and multiply life, to put this life in order? For such a power, execution was at the same time a limit, a scandal, and a contradiction. Hence capital punishment could not be maintained except by invoking less the enormity of the crime itself than the monstrosity of the criminal, his incorrigibility, and the safeguard of society. One had the right to kill those who represented a kind of biological danger to others.”— Michel Foucault, The History of Sexuality, Volume 1: An Introduction (1976)

“It seems likely that we will come to see in the next year a painful scenario in which some human creatures assert their rights to live at the expense of others, re-inscribing the spurious distinction between grievable and ungrievable lives, that is, those who should be protected against death at all costs and those whose lives are considered not worth safeguarding against illness and death. –”— Judith Butler, “Capitalism has its Limits.”

A letter from Tim Young, written in late March from San Quentin State Prison’s death row details his fears of the spread of COVID-19.1 According to Tim, one of the people in an adjacent cell was recently given a long swab through the meal tray slot on his cell door and told to insert it up his nostril. He was also instructed to do a throat swab. The next day, the man was taken to the Hole for quarantine—for the flu, according to the staff.2

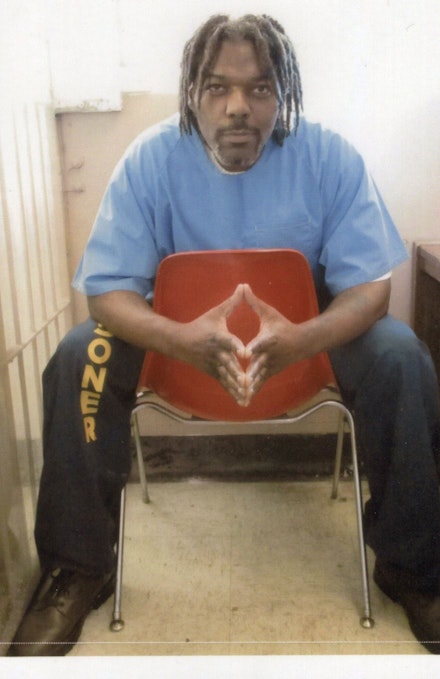

Tim Young. Photo: San Quentin Prison.

Tim Young. Photo: San Quentin Prison.

Tim writes that dozens of people in his unit have been similarly tested and quarantined, all diagnosed with the flu. In the letter, Tim’s frustration and fear is palpable. He writes about staff handling his food trays without gloves and sneezing and coughing as they walk along the walkway, stopping at each cell to unlock the slot in the door and push the food through the narrow spaces. The flu diagnoses and the cavalier attitudes of the staff towards hygiene have left Tim oscillating between concerns about the inadequacy of medical care in San Quentin and possible cover-ups. While, Tim explains, he is filing a legal request/complaint to be provided masks and gloves, and to require staff to wear them, the pervasive sense in his letter is that anything he does will be futile. This is most apparent when at the end of the letter he writes, "I feel like they are actually trying to spread the virus to us . . . it would be a solution on death row, after all."3

The coronavirus pandemic places in stark relief the complicated relationship, in the United States and globally, between the state and public health. The current conditions of what Michel Foucault named bio-power—the exercise of power through "the administration of bodies and the calculated management of life"—is called into question in the US as hospitals run out of ventilators and protective gear for their workers and as mass unemployment sweeps the nation, leaving people unsure of how they are going to keep feeding themselves and their families, or whether they will have housing in which to shelter-in-place.4 If power is, as Foucault defines it, the ability to "foster life or disallow it to the point of death," what happens within the relationships of power and biological life when death runs rampant?5

Clearly, taking heed of the changing nature of power at such a time is of utmost importance. Some are already reckoning with emergent biopolitical forms. Giorgio Agamben, for instance, fears that the medical emergency will allow state power to implement measures that can become permanent tools of governmental tyranny once the crisis is over.6 Today’s harsh emergency powers supposedly justified by the pandemic could become tomorrow’s "apparatuses of oppression."7

Tim’s letter, however, with his apprehension that, in the US, COVID-19 could be construed on death row as a governmental solution, implies that there is something else happening within this biopolitical shakeup. The conditions he refers to—the extreme of shoddy management of life (and death) captured in his description of swabs passed through slots, the coughing staff distributing food trays through locked gates, and the sick quarantined in the Hole—force the question of what can be learned about what we can call emergent viral biopolitics through the conditions endured by those who have been condemned to die.

Tim’s letter is a stark reminder that, even without a pandemic, death row has an uneasy relationship to bio-power. With state power wielded through the ability to “make live or let die,” those whom the legal apparatus of the state have condemned to die, but whose lives are instead maintained by the state, exist in an odd limbo.8 These are the living dead. They live only to be made to die, and they do so for years. The average time that people spend on death row in most of the US, kept alive by the state, is 15 years. In California, where Tim has been on death row for over 16 years, Governor Gavin Newsom has imposed a moratorium on the death penalty. The 737 people currently on death row in that state, including Tim, are now the living dead indefinitely, with the state charged with maintaining their lives—letting them live, in a reversal of Foucault’s terms—until it can make them die.9

Given this contradiction, a mass die-off from COVID-19 would seem to be a solution, to use Tim’s word, to a glitch in the biopolitical mechanisms of state governance. But this is too easy a conclusion. The death penalty has, after all, a strategic significance within the genealogy of bio-power, as Foucault outlines it in History of Sexuality, Volume I. Instead of a malfunction or an anomaly, it has always been a solution, within the changing forms of governance Foucault describes, if to a shifting problem.

To rehearse this history briefly, in the pre-modern exercise of power, the death penalty was the central means through which sovereign rulers exercised their authority. “Power in this instance was essentially a right of seizure: of things, time, bodies, and ultimately life itself; it culminated in the privilege to seize hold of life in order to suppress it."10 Governing power was administered through death and the threat of death, made manifest through the "elaborate ceremonials of monarchical sovereignty from the court to the scaffold; from the coronation to the fields of war."11

In modernity—roughly, since the 18th century—as power begins to operate through the management of life, capital punishment took on a different role. Foucault points out a seeming paradox: "How could power exercise its highest prerogatives by putting people to death, when its main role was to ensure, sustain and multiply life, to put this life in order?"12 The incongruity is resolved as execution becomes a social sorting mechanism. As Foucault explains, the death penalty comes to invoke “less the enormity of the crime itself than the monstrosity of the criminal, his incorrigibility, and the safeguard of society. One had the right to kill those who represented a kind of biological danger to others."13

This is the real paradox; the death penalty provides the answer for how power can hold authority without an ever-present threat of death. People now adhere to the workings of power thanks to more nuanced methods of coercion. This is the key to the most essential aspect of bio-power. When power becomes management—the ordering of life—it is exercised through the production of classifications that come to feel natural to people. Those condemned to death are the subjects of the ultimate classification within this system; they are those who are so monstrous they must die, even if their death is deferred.14 They serve as the end limit to all other classifications.

If this is how death row has served power in the U.S., and I believe it an apt description, the question returns: Within emergent viral biopolitics, how is death row being repositioned—made, as Tim fears, another solution—within the changing relations of power and biological life? What roles will the living dead, those made monsters and left to molder in modernity’s cages, play as the end limits of the social order necessarily adjust to a pandemic? Tim details the odd perversities of this shifting ordering. Although the governor of California issued a statewide shelter-in-place order on March 19, until March 27, when Tim and hundreds of others on death row received notice that a guard had tested positive for COVID-19, they were still given the option to go to the yard each day. When he describes the process of how people are taken to the yard, Tim moves into writing in third person as he explains why he has been choosing to stay in his cell for 24 hours a day and forgo going outside:

The protocol for yard release is as follows. The officer unlocks the tray slot, and instructs the prisoner to strip completely naked. They have the prisoner open his mouth, stick out his tongue, run his fingers through his hair, and after that, lift up his genitals. They instruct the prisoner to turn around, show the bottom of each foot, and then squat and cough. After the strip search, the prisoner is instructed to hand over any clothing or items that they are wearing or taking to the yard. The officers do a manual search of the prisoner’s property. After the inspection they return the prisoner's property back through the tray slot and instruct the prisoner to get dressed. Once the prisoner is dressed he is handcuffed through the tray slot. At that point the cell door is opened up. The prisoner is physically escorted downstairs to where he is scanned with a handheld metal detector, and his belongings are trolled through an x-ray machine.15

Tim notes that neither the guards nor the people being searched wear gloves or masks as they repeat this ritual of debasement. In a time of social distancing, the intimacy is shocking—all that touching. With both the staff and the people on death row ungloved and unmasked as clothing is taken off, passed back and forth, and put back on, the people who talk about COVID-19 as the great equalizer come to mind.16 No one, in what Tim describes, seems safe from the pandemic, regardless of who is clothed and who is made to squat and cough.

When Tim details the procedure that would allow him to leave his 10 by 4 1/2 foot cell, however, he makes it clear that there is nothing equal about the spread of the coronavirus in San Quentin. As he explains, visitation has been cancelled for weeks, and it is only through contact with the staff that the virus could wreak its havoc on the lockdown unit. This means the elaborate performance of safety, with the strip search enacted through a slot in the cell door, the handcuffs, and even the final extra step of the metal detectors, is a charade of security. The ritual of control actually fosters the spread of the virus from staff member to prisoner, staff member to prisoner, all the way down the long metal walkway of his 54-person tier and through the 540-person unit. Who is safe from whom?

In the time of COVID-19, what Tim recounts is not the procedures of security made ridiculous, or obsolete. It is, rather, the viral remaking of the death penalty. The intricate measures ensure that death row and its inhabitants are not immune from the pandemic. With each strip search—that extreme enactment of biological intimacy—they are instead centered within it, made probable carriers of the virus. If the death penalty delineates those at the end limits of the system supposedly serving the care and maintenance of life, the seemingly inept technologies of power that Tim describes ensures that those end limits are still operational within viral biopolitics. As the maximal variance within the social order, Tim and the other 736 people on California’s death row continue to make more palatable the vast inequities of that ordering, including normalizing who lives and who dies within the pandemic.

The emergent viral biopolitics encapsulated in Tim's letters is not entirely new. In 2003 Achille Mbembe challenged Foucault's idea that the maintenance of life is central to modern biopolitics by pointing to power’s propensity for killing and maiming.17 This could be seen in European colonial projects and slavery in the United States, and in "the contemporary ways in which the political, under the guise of war, of resistance, or of the fight against terror, makes the murder of the enemy its primary and absolute objective."18 Mbembe argued that the maintenance of life is certainly not always the object of power. Instead, "the ultimate expression of sovereignty resides, to a large degree, in the power and the capacity to dictate who may live and who must die."19

While this seemed a vital revision of Foucault’s ideas at the beginning of the 21st century, the pandemic now brings into question the first part of Mbembe's definition of power. The ability to "dictate who may live" is becoming more and more fraught. As death is rampant, with bodies piling up in morgues and hospitals, social and political structures all around us are being revealed to be incapable not only of the maintenance and care of life but even of the ability to allow persons to live—the “letting live” at the crux of biopower in all its forms. The US healthcare system is crumbling, with insufficient beds, respirators, and testing capacity. Millions and millions of people file for unemployment each week. And the estimated 550,000 people who are unhomed remain unable to shelter-in-place. The government is not "dictating" life in these conditions. COVID-19 reveals that all that is left in the US of technologies of power that once could either “make live or let die" or prescribe "who may live and who must die" is social ordering—the ability to make sense out of the lives and deaths in a pandemic. In emergent viral biopolitics, whether by design or inability, political power no longer maintains life, something the coronavirus has not caused but instead reveals. The maintenance of life falls now entirely within the realm of economics, decided by capital’s investment decisions; the socio-political serves primarily to demarcate those who can die without social remorse. And, with more and more statistics revealing the racialized and class paradigms of who is dying in the US, the system is hard at work.

In late March, Judith Butler warned that the coronavirus was sure to be another opportunity for "re-inscribing the spurious distinction between grievable and ungrievable lives, that is, those who should be protected against death at all costs and those whose lives are considered not worth safeguarding against illness and death."20 Those who are already the living dead—who can already be made dead within the social imaginary—are an obvious place to start the sorting. Of course it takes weeks for guards in San Quentin to be supplied with masks and gloves.

By the beginning of April, after Tim had spent 27 days without the yard or visitation and an uninterrupted 648 hours in his tiny cell, his hesitation to talk on the phone came up in a letter.21 Tim prefers writing letters; making a call in San Quentin is always frustrating. He has to first sign up for a time slot. Once his day and time come up, a guard wheels an ancient phone booth to his cell and passes the receiver through the slot in the door. The call is processed by GTL, a private corporation and "Corrections Innovations Leader," and the system makes it difficult and costly to accept his collect call.22 When calls do get through, Tim has 15 minutes to have a conversation that is closely monitored. An automated message breaks through the call every few minutes to explain the monitoring process, and the person doing the monitoring will sometimes end the call randomly. The bars of the prison never recede very far during these brief and fragmented conversations.23

With the severe social distancing that Tim is now subjected to, however, phone calls are a necessity. Mail service is more disrupted in San Quentin by the day, letters are taking longer and longer to get through, and the isolation is extreme. But now the phone has become perilous. As Tim explains, next to contact with staff, the phone is sure to be the biggest conduit of the virus.

"The phone is not being cleaned and sterilized between uses," Tim writes. "I would guess it never has been really cleaned, in all the years it's been pushed around the unit. And, we aren't being given gloves to handle it with. Instead, they have a towel attached to it now. We are supposed to use the towel to wipe the receiver before we use it." Tim continues, "I have no intentions of touching that shared towel."24

He has instead come up with his own method to clean the phone and a plan to avoid touching it with his bare hands. He also has a makeshift mask to wear when he uses the phone. Meanwhile, the towel hangs off the phone as a warning—or a message in code. What it is saying is that it does not matter if Tim touches the towel. And, although this is no reassurance to Tim, no one needs to die on death row from COVID-19. Tim and the rest of the living dead are already playing their role within emergent viral biopolitics. Those squatting and coughing to go into the yard, those who swipe the towel across the mouthpiece of the phone, and, even those who refuse to do this, have been remade once again as biological dangers, monsters who fall outside of structures of empathy and care. They are made to perform their monstrosity and normalize the shifting parameters of viral biopolitics.25 In fact, maybe it is better for those who exercise power that no one on death row does die because of the coronavirus. The living dead, remember, are monstrous because they do not die.

Tim does not mention his innocence claim often in the letters he writes. Only once did he note briefly that there is a witness who identified another shooter in the crime for which he has been sentenced to die. Another time, he wrote about the appellate court system, describing the difficulties of procuring a full reversal once one has been convicted of a crime. Instead, his letters usually are about strategies for organizing against the death penalty.

Tim well knows that the position he inhabits—a monster who will not die—is necessary to power in a time in which socio-political systems are no longer in place to maintain lives. So Tim, in what he calls his tiny "coffin-like cell," is made to both embody and hide the workings of emergent US biopolitics.26 This is a horrific position even outside the daily tortures of solitary confinement. To be the one who acts as the end limit of society’s ability to care is to be the proxy through which huge swathes of the population are made to join Tim as the living dead: the two million Palestinian people who have been imprisoned in Gaza under full military blockade with US backing for 12 years; the over 50,000 children detained by US immigration agencies; the US-imposed sanctions on Iran that are crippling the country’s ability to respond to COVID-19; the 15 million children (21 percent) living in poverty in the US; to name just some examples. Tim has been forced to figure within all of this suffering.27 His small cell gets crowded indeed.

When Tim organizes against the death penalty instead of around his own claims, this is not selflessness. It is instead an acknowledgment that against the potency of this power, even those deemed innocent within this system are still subject to its sorting. This means that what is required now is not organizing on any one person's behalf. Instead, as Tim demonstrates, we must act on behalf of all those whose lives will not be maintained by power, even as their deaths will certainly be made instrumental. We must fight back against both the impending waves of death and also resist the reanimation of the living dead.

Since August 2019, I have been corresponding with Tim Young, who has been on death row in San Quentin since 2006, as part of an art project by jackie sumell called Solitary Garden. Tim is a prolific writer and is very much my thought and writing partner on this essay, which could not have been conceived without him. Many of Tim’s letters and essays can be read at https://ias.ucsc.edu/timothyjamesyoung. Tim Young, “Letter to Rachel Nelson,” March 23, 2020. See also Tim’s recent essay: “Tim Young, Coronavirus: The Invisible Enemy Behind Enemy Lines,” SF Bay View National Black Newspaper, April 2020. https://sfbayview.com/2020/04/coronavirus-the-invisible-enemy-behind-enemy-lines/

What Tim calls the "Hole" is officially named the Adjustment Center (AC). It is the highest security unit at San Quentin and typically used to house people who have been found or alleged to have broken the rules of the institution. Tim Young, “Letter to Rachel Nelson,” April 2, 2020.

Tim Young, “Letter to Rachel Nelson,” March 23, 2020.

Michel Foucault, History of Sexuality: Volume 1, An Introduction, translated by Robert Hurley (New York: Random House, 1978), 140.

Ibid. 138.

In an article written at the very first stages of the COVID-19 epidemic in Italy, Agamben characterized the measures implemented in response to the COVID-19 pandemic as an exercise in the biopolitics of the “state of exception.” In an argument that was both polemical and dangerous as more and more people succumbed to the virus, Agamben wrote that the “invention of an epidemic offered the ideal pretext” for further limitations to basic freedoms. Recognizing that despite the problematic framework of the argument, that question about the biopolitical regime emerging in response to the coronavirus did warrant attention, the European Journal of Psychoanalysis put together a special section on “Coronavirus and philosophers” with a translation of Agamben’s polemic and the responses to it (February-March, 2020): http://www.journal-psychoanalysis.eu/coronavirus-and-philosophers/.

See also Panagiotis Sotiris’s reading, and rebuttal, of Agamben’s writings on COVID-19, which includes some examples of biopolitics within this current state of exception. Panagiotis Sotiris, “Against Agamben: Is a Democratic Biopolitics Possible?,” Viewpoint Magazine, March 20, 2020 https://www.viewpointmag.com/2020/03/20/against-agamben-democratic-biopolitics/.

Michel Foucault, “Society Must Be Defended”: Lectures at the College de France, 1975-76 (New York: Picador, 2003).

As I will discuss below, this is related to what Achille Mbembe calls necropolitics, the form of biopolitics born of colonization and slavery that takes its authority from “the capacity to dictate who may live and who must die.” There is a difference, however, that will be discussed subsequently. Achille Mbembe “Necropolitics.” Transl. Libby Meintjes. Public Culture15, no. 1 (Winter 2003): 11-40.

Foucault, History of Sexuality, 136

Michael Meranze, “Michel Foucault, the Death Penalty and the Crisis of Historical,” Historical Reflections / Réflexions Historiques 29, no. 2 (Summer 2003): Interpreting the Death Penalty: Spectacles and Debates, (Brooklyn: Berghahn 2003), 191-209.

Foucault. History of Sexuality. 138

Ibid.

It is imperative to note that in the lectures he gives towards the end of his life, Foucault names racism as another technology aimed at permitting the “sovereign right of death.” And, this is an interlocking point. In the US, not only are people of color disproportionately incarcerated, studies spanning more than 30 years covering virtually every state that uses capital punishment have found that race is a significant factor in death penalty cases.

Tim Young, “Letter to Rachel Nelson,” March 25, 2020.

Politicians and people insulated by wealth, including NY governor Andrew M. Coumo, have been seemingly impressed that celebrities, wealthy people, and politicians of different races and ethnicities—including elite White people—also contract the virus, leading some to call it the great equalizer. Of course, access to medical care and the ability to socially distance is clearly unequal, with employed poor people and people of color largely working as "essential workers" in food service, transportation, etc, with vastly different rates of contraction and mortality: Bethany L. Jones and Jonathan S. Jones, “Gov. Cuomo is Wrong, COVID-19 is Anything but an Equalizer,” Washington Post, April 5, 2020 https://www.washingtonpost.com/outlook/2020/04/05/gov-cuomo-is-wrong-covid-19-is-anything-an-equalizer/ and Akilah Johnson and Talia Buford, “Early Data Shows African Americans Have Contracted and Died of Coronavirus at an Alarming Rate,”ProPublica, April 3, 2020 https://www.propublica.org/article/early-data-shows-african-americans-have-contracted-and-died-of-coronavirus-at-an-alarming-rate.

Achille Mbembe. “Necropolitics.” Transl. Libby Meintjes. Public Culture 15, no. 1 (Winter 2003): 11-40. See also Jasbir Puar, The Right to Maim: Debility, Capacity, Disability. (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2017).

Mbembe 11

Ibid.

Butler also wrote, "Social and economic inequality will make sure that the virus discriminates. The virus alone does not discriminate, but we humans surely do, formed and animated as we are by the interlocking powers of nationalism, racism, xenophobia, and capitalism." Judith Butler, “Capitalism has its Limits," Verso Blog, March 30, 2020, https://www.versobooks.com/blogs/4603-capitalism-has-its-limits,

Tim Young, “Letter to Rachel Nelson,” April 2, 2020.

https://www.gtl.net/

Tim related this process both through a letter postmarked April 2 and a phone call on April 4. Tim Young, “Letter to Rachel Nelson,” April 2, 2020.

Ibid.

The racialized history of this kind of politics of performance is key here with much that could be said about the relationship to the performances forced from people enslaved. See Saidiya V. Hartman, Scenes of Subjection: Terror, Slavery, and Self-Making in Nineteenth Century America (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1997).

Tim Young, “Letter to Rachel Nelson,” August 8, 2019.

National Center for Children in Poverty, “Child Poverty,” http://www.nccp.org/topics/childpoverty.html.

“It seems likely that we will come to see in the next year a painful scenario in which some human creatures assert their rights to live at the expense of others, re-inscribing the spurious distinction between grievable and ungrievable lives, that is, those who should be protected against death at all costs and those whose lives are considered not worth safeguarding against illness and death. –”— Judith Butler, “Capitalism has its Limits.”

A letter from Tim Young, written in late March from San Quentin State Prison’s death row details his fears of the spread of COVID-19.1 According to Tim, one of the people in an adjacent cell was recently given a long swab through the meal tray slot on his cell door and told to insert it up his nostril. He was also instructed to do a throat swab. The next day, the man was taken to the Hole for quarantine—for the flu, according to the staff.2

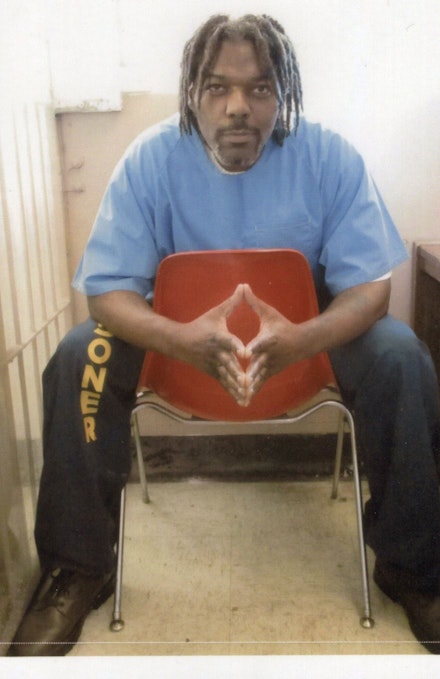

Tim Young. Photo: San Quentin Prison.

Tim Young. Photo: San Quentin Prison.Tim writes that dozens of people in his unit have been similarly tested and quarantined, all diagnosed with the flu. In the letter, Tim’s frustration and fear is palpable. He writes about staff handling his food trays without gloves and sneezing and coughing as they walk along the walkway, stopping at each cell to unlock the slot in the door and push the food through the narrow spaces. The flu diagnoses and the cavalier attitudes of the staff towards hygiene have left Tim oscillating between concerns about the inadequacy of medical care in San Quentin and possible cover-ups. While, Tim explains, he is filing a legal request/complaint to be provided masks and gloves, and to require staff to wear them, the pervasive sense in his letter is that anything he does will be futile. This is most apparent when at the end of the letter he writes, "I feel like they are actually trying to spread the virus to us . . . it would be a solution on death row, after all."3

The coronavirus pandemic places in stark relief the complicated relationship, in the United States and globally, between the state and public health. The current conditions of what Michel Foucault named bio-power—the exercise of power through "the administration of bodies and the calculated management of life"—is called into question in the US as hospitals run out of ventilators and protective gear for their workers and as mass unemployment sweeps the nation, leaving people unsure of how they are going to keep feeding themselves and their families, or whether they will have housing in which to shelter-in-place.4 If power is, as Foucault defines it, the ability to "foster life or disallow it to the point of death," what happens within the relationships of power and biological life when death runs rampant?5

Clearly, taking heed of the changing nature of power at such a time is of utmost importance. Some are already reckoning with emergent biopolitical forms. Giorgio Agamben, for instance, fears that the medical emergency will allow state power to implement measures that can become permanent tools of governmental tyranny once the crisis is over.6 Today’s harsh emergency powers supposedly justified by the pandemic could become tomorrow’s "apparatuses of oppression."7

Tim’s letter, however, with his apprehension that, in the US, COVID-19 could be construed on death row as a governmental solution, implies that there is something else happening within this biopolitical shakeup. The conditions he refers to—the extreme of shoddy management of life (and death) captured in his description of swabs passed through slots, the coughing staff distributing food trays through locked gates, and the sick quarantined in the Hole—force the question of what can be learned about what we can call emergent viral biopolitics through the conditions endured by those who have been condemned to die.

Tim’s letter is a stark reminder that, even without a pandemic, death row has an uneasy relationship to bio-power. With state power wielded through the ability to “make live or let die,” those whom the legal apparatus of the state have condemned to die, but whose lives are instead maintained by the state, exist in an odd limbo.8 These are the living dead. They live only to be made to die, and they do so for years. The average time that people spend on death row in most of the US, kept alive by the state, is 15 years. In California, where Tim has been on death row for over 16 years, Governor Gavin Newsom has imposed a moratorium on the death penalty. The 737 people currently on death row in that state, including Tim, are now the living dead indefinitely, with the state charged with maintaining their lives—letting them live, in a reversal of Foucault’s terms—until it can make them die.9

Given this contradiction, a mass die-off from COVID-19 would seem to be a solution, to use Tim’s word, to a glitch in the biopolitical mechanisms of state governance. But this is too easy a conclusion. The death penalty has, after all, a strategic significance within the genealogy of bio-power, as Foucault outlines it in History of Sexuality, Volume I. Instead of a malfunction or an anomaly, it has always been a solution, within the changing forms of governance Foucault describes, if to a shifting problem.

To rehearse this history briefly, in the pre-modern exercise of power, the death penalty was the central means through which sovereign rulers exercised their authority. “Power in this instance was essentially a right of seizure: of things, time, bodies, and ultimately life itself; it culminated in the privilege to seize hold of life in order to suppress it."10 Governing power was administered through death and the threat of death, made manifest through the "elaborate ceremonials of monarchical sovereignty from the court to the scaffold; from the coronation to the fields of war."11

In modernity—roughly, since the 18th century—as power begins to operate through the management of life, capital punishment took on a different role. Foucault points out a seeming paradox: "How could power exercise its highest prerogatives by putting people to death, when its main role was to ensure, sustain and multiply life, to put this life in order?"12 The incongruity is resolved as execution becomes a social sorting mechanism. As Foucault explains, the death penalty comes to invoke “less the enormity of the crime itself than the monstrosity of the criminal, his incorrigibility, and the safeguard of society. One had the right to kill those who represented a kind of biological danger to others."13

This is the real paradox; the death penalty provides the answer for how power can hold authority without an ever-present threat of death. People now adhere to the workings of power thanks to more nuanced methods of coercion. This is the key to the most essential aspect of bio-power. When power becomes management—the ordering of life—it is exercised through the production of classifications that come to feel natural to people. Those condemned to death are the subjects of the ultimate classification within this system; they are those who are so monstrous they must die, even if their death is deferred.14 They serve as the end limit to all other classifications.

If this is how death row has served power in the U.S., and I believe it an apt description, the question returns: Within emergent viral biopolitics, how is death row being repositioned—made, as Tim fears, another solution—within the changing relations of power and biological life? What roles will the living dead, those made monsters and left to molder in modernity’s cages, play as the end limits of the social order necessarily adjust to a pandemic? Tim details the odd perversities of this shifting ordering. Although the governor of California issued a statewide shelter-in-place order on March 19, until March 27, when Tim and hundreds of others on death row received notice that a guard had tested positive for COVID-19, they were still given the option to go to the yard each day. When he describes the process of how people are taken to the yard, Tim moves into writing in third person as he explains why he has been choosing to stay in his cell for 24 hours a day and forgo going outside:

The protocol for yard release is as follows. The officer unlocks the tray slot, and instructs the prisoner to strip completely naked. They have the prisoner open his mouth, stick out his tongue, run his fingers through his hair, and after that, lift up his genitals. They instruct the prisoner to turn around, show the bottom of each foot, and then squat and cough. After the strip search, the prisoner is instructed to hand over any clothing or items that they are wearing or taking to the yard. The officers do a manual search of the prisoner’s property. After the inspection they return the prisoner's property back through the tray slot and instruct the prisoner to get dressed. Once the prisoner is dressed he is handcuffed through the tray slot. At that point the cell door is opened up. The prisoner is physically escorted downstairs to where he is scanned with a handheld metal detector, and his belongings are trolled through an x-ray machine.15

Tim notes that neither the guards nor the people being searched wear gloves or masks as they repeat this ritual of debasement. In a time of social distancing, the intimacy is shocking—all that touching. With both the staff and the people on death row ungloved and unmasked as clothing is taken off, passed back and forth, and put back on, the people who talk about COVID-19 as the great equalizer come to mind.16 No one, in what Tim describes, seems safe from the pandemic, regardless of who is clothed and who is made to squat and cough.

When Tim details the procedure that would allow him to leave his 10 by 4 1/2 foot cell, however, he makes it clear that there is nothing equal about the spread of the coronavirus in San Quentin. As he explains, visitation has been cancelled for weeks, and it is only through contact with the staff that the virus could wreak its havoc on the lockdown unit. This means the elaborate performance of safety, with the strip search enacted through a slot in the cell door, the handcuffs, and even the final extra step of the metal detectors, is a charade of security. The ritual of control actually fosters the spread of the virus from staff member to prisoner, staff member to prisoner, all the way down the long metal walkway of his 54-person tier and through the 540-person unit. Who is safe from whom?

In the time of COVID-19, what Tim recounts is not the procedures of security made ridiculous, or obsolete. It is, rather, the viral remaking of the death penalty. The intricate measures ensure that death row and its inhabitants are not immune from the pandemic. With each strip search—that extreme enactment of biological intimacy—they are instead centered within it, made probable carriers of the virus. If the death penalty delineates those at the end limits of the system supposedly serving the care and maintenance of life, the seemingly inept technologies of power that Tim describes ensures that those end limits are still operational within viral biopolitics. As the maximal variance within the social order, Tim and the other 736 people on California’s death row continue to make more palatable the vast inequities of that ordering, including normalizing who lives and who dies within the pandemic.

The emergent viral biopolitics encapsulated in Tim's letters is not entirely new. In 2003 Achille Mbembe challenged Foucault's idea that the maintenance of life is central to modern biopolitics by pointing to power’s propensity for killing and maiming.17 This could be seen in European colonial projects and slavery in the United States, and in "the contemporary ways in which the political, under the guise of war, of resistance, or of the fight against terror, makes the murder of the enemy its primary and absolute objective."18 Mbembe argued that the maintenance of life is certainly not always the object of power. Instead, "the ultimate expression of sovereignty resides, to a large degree, in the power and the capacity to dictate who may live and who must die."19

While this seemed a vital revision of Foucault’s ideas at the beginning of the 21st century, the pandemic now brings into question the first part of Mbembe's definition of power. The ability to "dictate who may live" is becoming more and more fraught. As death is rampant, with bodies piling up in morgues and hospitals, social and political structures all around us are being revealed to be incapable not only of the maintenance and care of life but even of the ability to allow persons to live—the “letting live” at the crux of biopower in all its forms. The US healthcare system is crumbling, with insufficient beds, respirators, and testing capacity. Millions and millions of people file for unemployment each week. And the estimated 550,000 people who are unhomed remain unable to shelter-in-place. The government is not "dictating" life in these conditions. COVID-19 reveals that all that is left in the US of technologies of power that once could either “make live or let die" or prescribe "who may live and who must die" is social ordering—the ability to make sense out of the lives and deaths in a pandemic. In emergent viral biopolitics, whether by design or inability, political power no longer maintains life, something the coronavirus has not caused but instead reveals. The maintenance of life falls now entirely within the realm of economics, decided by capital’s investment decisions; the socio-political serves primarily to demarcate those who can die without social remorse. And, with more and more statistics revealing the racialized and class paradigms of who is dying in the US, the system is hard at work.

In late March, Judith Butler warned that the coronavirus was sure to be another opportunity for "re-inscribing the spurious distinction between grievable and ungrievable lives, that is, those who should be protected against death at all costs and those whose lives are considered not worth safeguarding against illness and death."20 Those who are already the living dead—who can already be made dead within the social imaginary—are an obvious place to start the sorting. Of course it takes weeks for guards in San Quentin to be supplied with masks and gloves.

By the beginning of April, after Tim had spent 27 days without the yard or visitation and an uninterrupted 648 hours in his tiny cell, his hesitation to talk on the phone came up in a letter.21 Tim prefers writing letters; making a call in San Quentin is always frustrating. He has to first sign up for a time slot. Once his day and time come up, a guard wheels an ancient phone booth to his cell and passes the receiver through the slot in the door. The call is processed by GTL, a private corporation and "Corrections Innovations Leader," and the system makes it difficult and costly to accept his collect call.22 When calls do get through, Tim has 15 minutes to have a conversation that is closely monitored. An automated message breaks through the call every few minutes to explain the monitoring process, and the person doing the monitoring will sometimes end the call randomly. The bars of the prison never recede very far during these brief and fragmented conversations.23

With the severe social distancing that Tim is now subjected to, however, phone calls are a necessity. Mail service is more disrupted in San Quentin by the day, letters are taking longer and longer to get through, and the isolation is extreme. But now the phone has become perilous. As Tim explains, next to contact with staff, the phone is sure to be the biggest conduit of the virus.

"The phone is not being cleaned and sterilized between uses," Tim writes. "I would guess it never has been really cleaned, in all the years it's been pushed around the unit. And, we aren't being given gloves to handle it with. Instead, they have a towel attached to it now. We are supposed to use the towel to wipe the receiver before we use it." Tim continues, "I have no intentions of touching that shared towel."24

He has instead come up with his own method to clean the phone and a plan to avoid touching it with his bare hands. He also has a makeshift mask to wear when he uses the phone. Meanwhile, the towel hangs off the phone as a warning—or a message in code. What it is saying is that it does not matter if Tim touches the towel. And, although this is no reassurance to Tim, no one needs to die on death row from COVID-19. Tim and the rest of the living dead are already playing their role within emergent viral biopolitics. Those squatting and coughing to go into the yard, those who swipe the towel across the mouthpiece of the phone, and, even those who refuse to do this, have been remade once again as biological dangers, monsters who fall outside of structures of empathy and care. They are made to perform their monstrosity and normalize the shifting parameters of viral biopolitics.25 In fact, maybe it is better for those who exercise power that no one on death row does die because of the coronavirus. The living dead, remember, are monstrous because they do not die.

Tim does not mention his innocence claim often in the letters he writes. Only once did he note briefly that there is a witness who identified another shooter in the crime for which he has been sentenced to die. Another time, he wrote about the appellate court system, describing the difficulties of procuring a full reversal once one has been convicted of a crime. Instead, his letters usually are about strategies for organizing against the death penalty.

Tim well knows that the position he inhabits—a monster who will not die—is necessary to power in a time in which socio-political systems are no longer in place to maintain lives. So Tim, in what he calls his tiny "coffin-like cell," is made to both embody and hide the workings of emergent US biopolitics.26 This is a horrific position even outside the daily tortures of solitary confinement. To be the one who acts as the end limit of society’s ability to care is to be the proxy through which huge swathes of the population are made to join Tim as the living dead: the two million Palestinian people who have been imprisoned in Gaza under full military blockade with US backing for 12 years; the over 50,000 children detained by US immigration agencies; the US-imposed sanctions on Iran that are crippling the country’s ability to respond to COVID-19; the 15 million children (21 percent) living in poverty in the US; to name just some examples. Tim has been forced to figure within all of this suffering.27 His small cell gets crowded indeed.

When Tim organizes against the death penalty instead of around his own claims, this is not selflessness. It is instead an acknowledgment that against the potency of this power, even those deemed innocent within this system are still subject to its sorting. This means that what is required now is not organizing on any one person's behalf. Instead, as Tim demonstrates, we must act on behalf of all those whose lives will not be maintained by power, even as their deaths will certainly be made instrumental. We must fight back against both the impending waves of death and also resist the reanimation of the living dead.

Since August 2019, I have been corresponding with Tim Young, who has been on death row in San Quentin since 2006, as part of an art project by jackie sumell called Solitary Garden. Tim is a prolific writer and is very much my thought and writing partner on this essay, which could not have been conceived without him. Many of Tim’s letters and essays can be read at https://ias.ucsc.edu/timothyjamesyoung. Tim Young, “Letter to Rachel Nelson,” March 23, 2020. See also Tim’s recent essay: “Tim Young, Coronavirus: The Invisible Enemy Behind Enemy Lines,” SF Bay View National Black Newspaper, April 2020. https://sfbayview.com/2020/04/coronavirus-the-invisible-enemy-behind-enemy-lines/

What Tim calls the "Hole" is officially named the Adjustment Center (AC). It is the highest security unit at San Quentin and typically used to house people who have been found or alleged to have broken the rules of the institution. Tim Young, “Letter to Rachel Nelson,” April 2, 2020.

Tim Young, “Letter to Rachel Nelson,” March 23, 2020.

Michel Foucault, History of Sexuality: Volume 1, An Introduction, translated by Robert Hurley (New York: Random House, 1978), 140.

Ibid. 138.

In an article written at the very first stages of the COVID-19 epidemic in Italy, Agamben characterized the measures implemented in response to the COVID-19 pandemic as an exercise in the biopolitics of the “state of exception.” In an argument that was both polemical and dangerous as more and more people succumbed to the virus, Agamben wrote that the “invention of an epidemic offered the ideal pretext” for further limitations to basic freedoms. Recognizing that despite the problematic framework of the argument, that question about the biopolitical regime emerging in response to the coronavirus did warrant attention, the European Journal of Psychoanalysis put together a special section on “Coronavirus and philosophers” with a translation of Agamben’s polemic and the responses to it (February-March, 2020): http://www.journal-psychoanalysis.eu/coronavirus-and-philosophers/.

See also Panagiotis Sotiris’s reading, and rebuttal, of Agamben’s writings on COVID-19, which includes some examples of biopolitics within this current state of exception. Panagiotis Sotiris, “Against Agamben: Is a Democratic Biopolitics Possible?,” Viewpoint Magazine, March 20, 2020 https://www.viewpointmag.com/2020/03/20/against-agamben-democratic-biopolitics/.

Michel Foucault, “Society Must Be Defended”: Lectures at the College de France, 1975-76 (New York: Picador, 2003).

As I will discuss below, this is related to what Achille Mbembe calls necropolitics, the form of biopolitics born of colonization and slavery that takes its authority from “the capacity to dictate who may live and who must die.” There is a difference, however, that will be discussed subsequently. Achille Mbembe “Necropolitics.” Transl. Libby Meintjes. Public Culture15, no. 1 (Winter 2003): 11-40.

Foucault, History of Sexuality, 136

Michael Meranze, “Michel Foucault, the Death Penalty and the Crisis of Historical,” Historical Reflections / Réflexions Historiques 29, no. 2 (Summer 2003): Interpreting the Death Penalty: Spectacles and Debates, (Brooklyn: Berghahn 2003), 191-209.

Foucault. History of Sexuality. 138

Ibid.

It is imperative to note that in the lectures he gives towards the end of his life, Foucault names racism as another technology aimed at permitting the “sovereign right of death.” And, this is an interlocking point. In the US, not only are people of color disproportionately incarcerated, studies spanning more than 30 years covering virtually every state that uses capital punishment have found that race is a significant factor in death penalty cases.

Tim Young, “Letter to Rachel Nelson,” March 25, 2020.

Politicians and people insulated by wealth, including NY governor Andrew M. Coumo, have been seemingly impressed that celebrities, wealthy people, and politicians of different races and ethnicities—including elite White people—also contract the virus, leading some to call it the great equalizer. Of course, access to medical care and the ability to socially distance is clearly unequal, with employed poor people and people of color largely working as "essential workers" in food service, transportation, etc, with vastly different rates of contraction and mortality: Bethany L. Jones and Jonathan S. Jones, “Gov. Cuomo is Wrong, COVID-19 is Anything but an Equalizer,” Washington Post, April 5, 2020 https://www.washingtonpost.com/outlook/2020/04/05/gov-cuomo-is-wrong-covid-19-is-anything-an-equalizer/ and Akilah Johnson and Talia Buford, “Early Data Shows African Americans Have Contracted and Died of Coronavirus at an Alarming Rate,”ProPublica, April 3, 2020 https://www.propublica.org/article/early-data-shows-african-americans-have-contracted-and-died-of-coronavirus-at-an-alarming-rate.

Achille Mbembe. “Necropolitics.” Transl. Libby Meintjes. Public Culture 15, no. 1 (Winter 2003): 11-40. See also Jasbir Puar, The Right to Maim: Debility, Capacity, Disability. (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2017).

Mbembe 11

Ibid.

Butler also wrote, "Social and economic inequality will make sure that the virus discriminates. The virus alone does not discriminate, but we humans surely do, formed and animated as we are by the interlocking powers of nationalism, racism, xenophobia, and capitalism." Judith Butler, “Capitalism has its Limits," Verso Blog, March 30, 2020, https://www.versobooks.com/blogs/4603-capitalism-has-its-limits,

Tim Young, “Letter to Rachel Nelson,” April 2, 2020.

https://www.gtl.net/

Tim related this process both through a letter postmarked April 2 and a phone call on April 4. Tim Young, “Letter to Rachel Nelson,” April 2, 2020.

Ibid.

The racialized history of this kind of politics of performance is key here with much that could be said about the relationship to the performances forced from people enslaved. See Saidiya V. Hartman, Scenes of Subjection: Terror, Slavery, and Self-Making in Nineteenth Century America (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1997).

Tim Young, “Letter to Rachel Nelson,” August 8, 2019.

National Center for Children in Poverty, “Child Poverty,” http://www.nccp.org/topics/childpoverty.html.

Contributor

Rachel Nelson

is interim director of UC Santa Cruz Institute of the Arts and Sciences. Nelson has curated and organized numerous exhibitions and programs and has published exhibition catalogues, journal articles, book chapters, and reviews, including in the forthcoming Under the Skin (Oxford University Press).

is interim director of UC Santa Cruz Institute of the Arts and Sciences. Nelson has curated and organized numerous exhibitions and programs and has published exhibition catalogues, journal articles, book chapters, and reviews, including in the forthcoming Under the Skin (Oxford University Press).

No comments:

Post a Comment