Post Magazine / Books

Review | The Road: new book shines a light on Indonesia’s 50-year forgotten war in West Papua as it flares again

Australian journalist John Martinkus documents West Papuan indigenous tribes’ fight to recover ancestral lands annexed by Indonesia

Construction of a controversial highway sparked an escalation last year with Indonesia deploying troops and chemical weapons

Tom Fawthrop 6 Jun, 2020

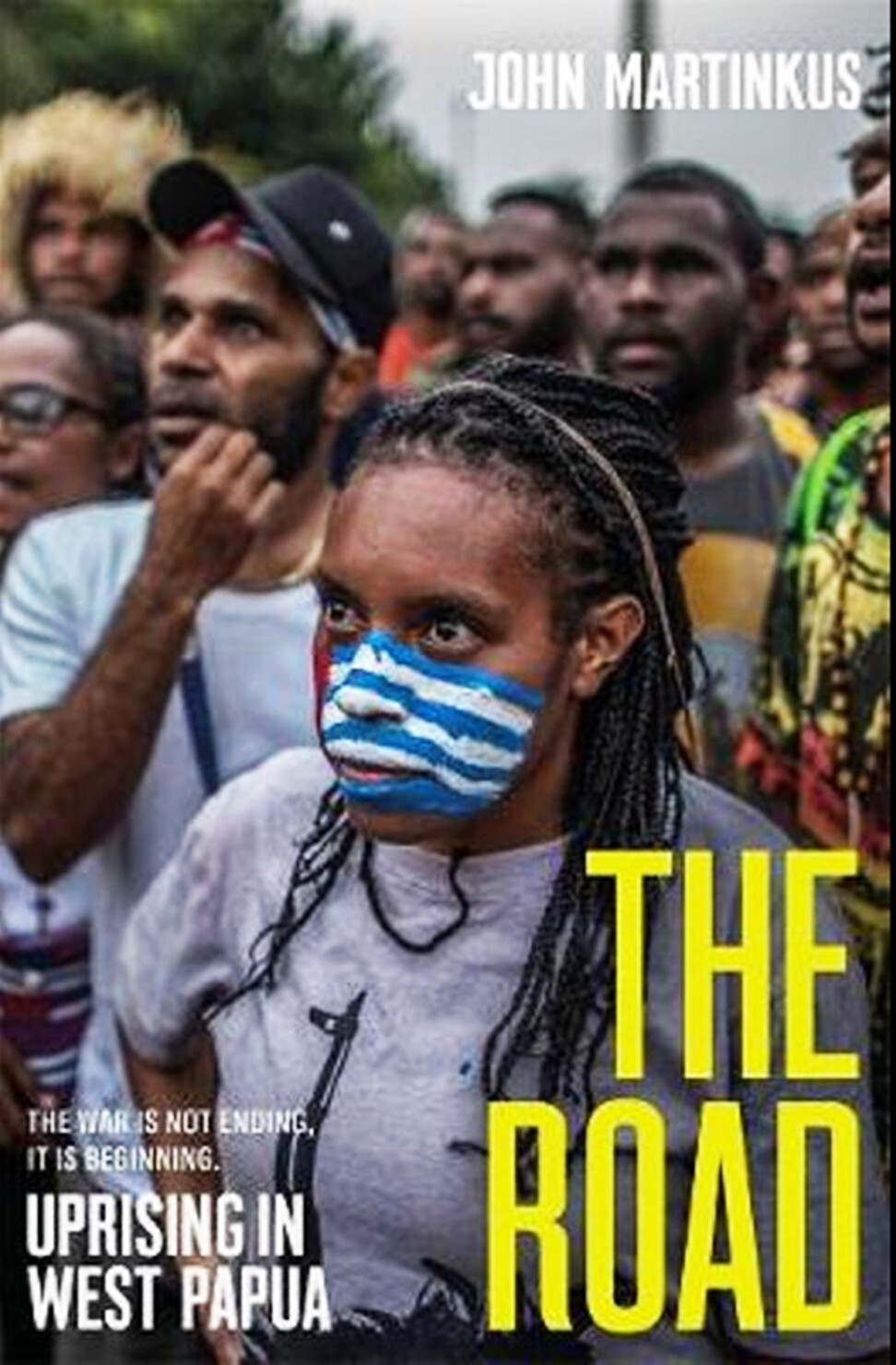

Central Highlands villagers, shown here with the Morning Star flag in the West Papua capital, have been fighting to recover their ancestral lands for 50 years. Picture: Getty Images

The Road: Uprising in West Papua

by John Martinkus

Black Inc

3.5/5 stars

Australian journalist John Martinkus documents West Papuan indigenous tribes’ fight to recover ancestral lands annexed by Indonesia

Construction of a controversial highway sparked an escalation last year with Indonesia deploying troops and chemical weapons

Tom Fawthrop 6 Jun, 2020

Central Highlands villagers, shown here with the Morning Star flag in the West Papua capital, have been fighting to recover their ancestral lands for 50 years. Picture: Getty Images

The Road: Uprising in West Papua

by John Martinkus

Black Inc

3.5/5 stars

After 50 years of popular resistance to Indonesian rule in West Papua, this forgotten war is flaring up again.

The indigenous movement, led by the United Liberation Movement for West Papua (ULMWP), has never lost hope of recovering ancestral lands dating back centuries before their annexation by Indonesia.

Military operations intensified in the Central Highlands region of Nduga last year as the uprising spread. Another 16,000 troops were dispatched to protect the construction of a controversial Trans-Papua Highway. Helicopters dropped bombs and strafed villages. About 45,000 refugees fled across the border into Papua New Guinea.

“It is the helicopters that are the worst. They are used as platforms to shoot or drop white phosphorous grenades or bomblets that inflict horrible injuries on the populace,” John Martinkus writes in his new book, The Road: Uprising in West Papua.

Martinkus depicts a dirty little war far removed from the glittering shopping malls of Jakarta, in a distant outpost of the vast Indonesian archipelago, hidden from the world. The Indonesian military denies it uses white phosphorus, a banned agent of chemical warfare. But photos of the Papuan victims in the book display gruesome wounds consistent with this chemical.

The Australian journalist has risked his life many times bringing news from the front lines in East Timor and Aceh, and is now committed to lifting the veil of secrecy over West Papua. At least eight foreign journalists – including Australian, Dutch and Swiss – have died reporting from these Indonesian war zones.

Martinkus writes: “After seeing the violence and knowing people the Indonesian security forces have killed, tortured and jailed in East Timor, Aceh and Papua, I cannot, as a human being and a journalist, walk away from this story and let the lies, obfuscations and outright atrocities against the people of those three Indonesian conflicts go unreported.”

The Indonesian government has a different narrative. It says it wants to bring development to a remote province by building an ambitious road – the 4,300km Trans-Papua Highway, costing US$1.4 billion – through the jungle to bring “wealth, development and prosperity” to the isolated regions of West Papua.

But that is not how West Papuans see it, according to Martinkus. “The road would bring the death of their centuries-old way of life. The highway brings military occupation by Indonesian troops, exploitation by foreign companies, environmental destruction and colonisation by Indonesian transmigrants from other provinces.” This mineral-rich region hosts the world’s largest gold mine and second largest copper mine.

The Suharto-era transmigrasi policy involved organising a massive migration of farmers from overpopulated Java to become settlers in West Papua. Many believe the highway will increase the number of settlers and the Melanesian tribes are convinced this will pave the way for their cultural extinction.

Author John Martinkus. Photo: Handout

When East Papua celebrated its independence, in 1975, as Papua New Guinea, the western part of the island was saddled with a shoddy United Nations-brokered deal (1969) awarding de facto sovereignty to Indonesia. Papuans passionately believe they were cheated.

While the book draws many parallels between the East Timor and West Papua conflicts, it does not give enough coverage to the major differences between the two liberation struggles. In the case of West Papua, Indonesia steadfastly claims the 1969 UN agreement granted it eternal sovereignty over West Papua.

Key Western governments – the United States, Britain and France on the UN Security Council, and Australia, Indonesia’s closest neighbour – all have substantial business investment, trade and military ties with Jakarta. They are only too happy to support Jakarta’s narrative that it is fighting a “separatist rebellion” and defending its sovereign territory.

By appointing a controversial general, Wiranto – who goes by one name – as the senior minister dealing with West Papua, Indonesian President Joko Widodo has tied himself to a militarist policy. Wiranto was indicted for crimes against humanity in East Timor by a UN court in 2003, but Jakarta declined to hand him over.

Two decades later, Wiranto has rejected all Papuan demands to end the war by agreeing to a referendum with the words: “The door is closed to any referendum.”

Indonesian President Joko Widodo (second right) with his delegation to look at the Trans-Papua Highway. Photo: AFP

The big difference with East Timor was that the UN never recognised Jakarta’s annexation and, together with former colonial power Portugal, pushed for the referendum that delivered independence.

In 2019, after years of isolation, a diplomatic campaign by the ULMWP took off. The group was granted observer status at the Pacific Islands Forum and its call for a referendum was backed at the UN General Assembly by several Melanesian governments.

Last year, the exiled West Papuan leader and ULMWP chairman, Benny Wenda, delivered a historic petition with 1.8 million signatures to Michelle Bachelet, director of the UN Human Rights Council. It was smuggled out from the West Papua jungles on a long, perilous journey to her office in Geneva, Switzerland. Bachelet has expressed grave concern over the situation in West Papua but, predictably, Jakarta has denied her requests to allow a UN human rights mission access to the region.

With no referendum or international effort to restrain the Indonesian army, this book serves as grim reminder that another genocide could be in the making and, like the Rohingya in Myanmar, another outpouring of refugees.

No comments:

Post a Comment