UPDATED

US Supreme Court rules half of Oklahoma is Native American land

TO BLACK AMERICANS.

SHUTTERSTOCK

SHUTTERSTOCK

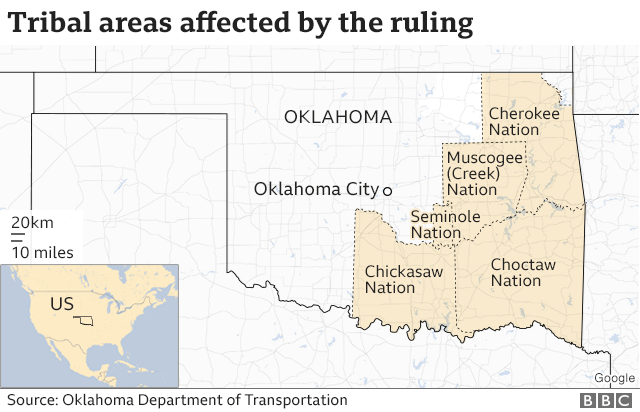

The US Supreme Court has ruled about half of Oklahoma belongs to Native Americans, in a landmark case that also quashed a child rape conviction.

The justices decided 5-4 that an eastern chunk of the state, including its second-biggest city, Tulsa, should be recognised as part of a reservation.

Jimcy McGirt, who was convicted in 1997 of raping a girl, brought the case.

He cited the historical claim of the Muscogee (Creek) Nation to the land where the assault occurred.

What does the ruling mean?

Thursday's decision in McGirt v Oklahoma is seen as one of the most far-reaching cases for Native Americans before the highest US court in decades.

The ruling means some tribe members found guilty in state courts for offences committed on the land at issue can now challenge their convictions.

Only federal prosecutors will have the power to criminally prosecute Native Americans accused of crimes in the area.

Tribe members who live within the boundaries may also be exempt from state taxes, according to Reuters news agency.

Some 1.8 million people - of whom about 15% are Native American - live on the land, which spans three million acres.

What did the justices say?

Justice Neil Gorsuch, a conservative appointed by US President Donald Trump, sided with the court's four liberals and also wrote the opinion.

He referred to the Trail of Tears, the forcible 19th Century relocation of Native Americans, including the Creek Nation, to Oklahoma.

The US government said at the time that the new land would belong to the tribes in perpetuity.

Justice Gorsuch wrote: "Today we are asked whether the land these treaties promised remains an Indian reservation for purposes of federal criminal law.

"Because Congress has not said otherwise, we hold the government to its word."

What about the rape case?

The ruling overturned McGirt's prison sentence. He could still, however, be tried in federal court.

McGirt, now 71, was convicted in 1997 in Wagoner County of raping a four-year-old girl.

He did not dispute his guilt before the Supreme Court, but argued that only federal authorities should have been entitled to prosecute him.

McGirt is a member of the Seminole Nation.

His lawyer, Ian Heath Gershengorn, told CNBC: "The Supreme Court reaffirmed today that when the United States makes promises, the courts will keep those promises."

How might Oklahoma's criminal justice system be affected?

In a dissenting opinion, Chief Justice John Roberts said the decision would destabilise the state's courts.

He wrote: "The State's ability to prosecute serious crimes will be hobbled and decades of past convictions could well be thrown out.

"The decision today creates significant uncertainty for the State's continuing authority over any area that touches Indian affairs, ranging from zoning and taxation to family and environmental law."

An analysis by The Atlantic magazine of Oklahoma Department of Corrections records found that 1,887 Native Americans were in prison as of the end of last year for offences committed within the boundaries of the tribal territory.

But fewer than one in 10 of those cases would qualify for a new federal trial, according to the research.

Jonodev Chaudhuri, a former chief justice of the Muscogee Nation's Supreme Court, dismissed talk of legal mayhem.

He told the Tulsa World newspaper: "All the sky-is-falling narratives were dubious at best.

"This would only apply to a small subset of Native Americans committing crimes within the boundaries."

How did other tribal leaders react?

In a joint statement, the Five Tribes of Oklahoma - Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw and Seminole and Muscogee Nation - welcomed the ruling.

They pledged to work with federal and state authorities to agree shared jurisdiction over the land.

"The Nations and the state are committed to implementing a framework of shared jurisdiction that will preserve sovereign interests and rights to self-government while affirming jurisdictional understandings, procedures, laws and regulations that support public safety, our economy and private property rights," the statement said.

SCOTUS Refuses to Sanction the Robbery of Tribal Lands

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/67040981/1051514332.jpg.0.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment