MARK MACKINNON

SENIOR INTERNATIONAL CORRESPONDENT

LONDON PUBLISHED AUGUST 5, 2020

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/tgam/LZN3CBALERIGDBU7UKBMAJJBBM.jpg)

A survivor is taken out of the rubble after a massive explosion in Beirut, Lebanon.

HASSAN AMMAR/THE ASSOCIATED PRESS

1 of 19 https://www.theglobeandmail.com/world/article-how-an-abandoned-ship-became-a-ticking-time-bomb-in-beirut/

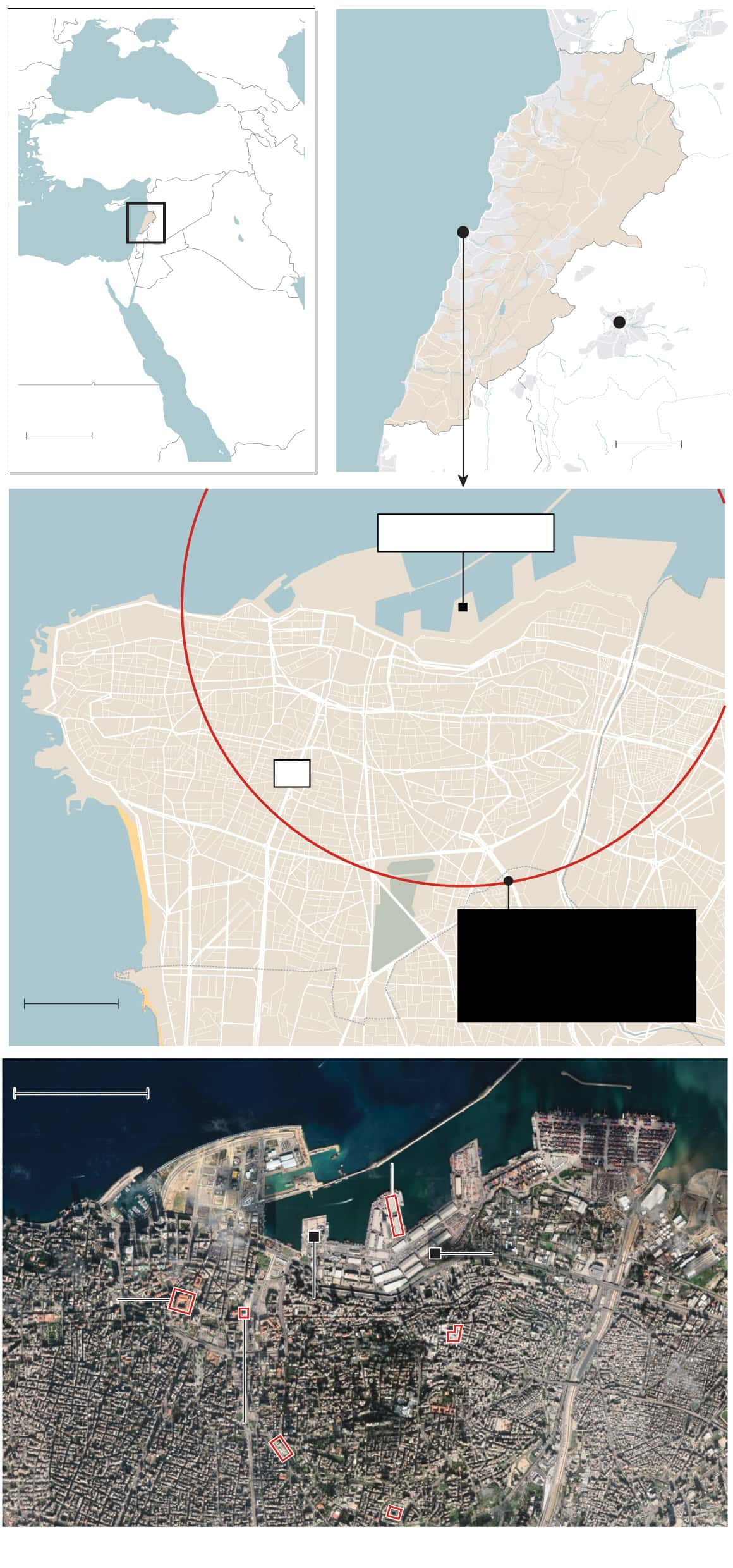

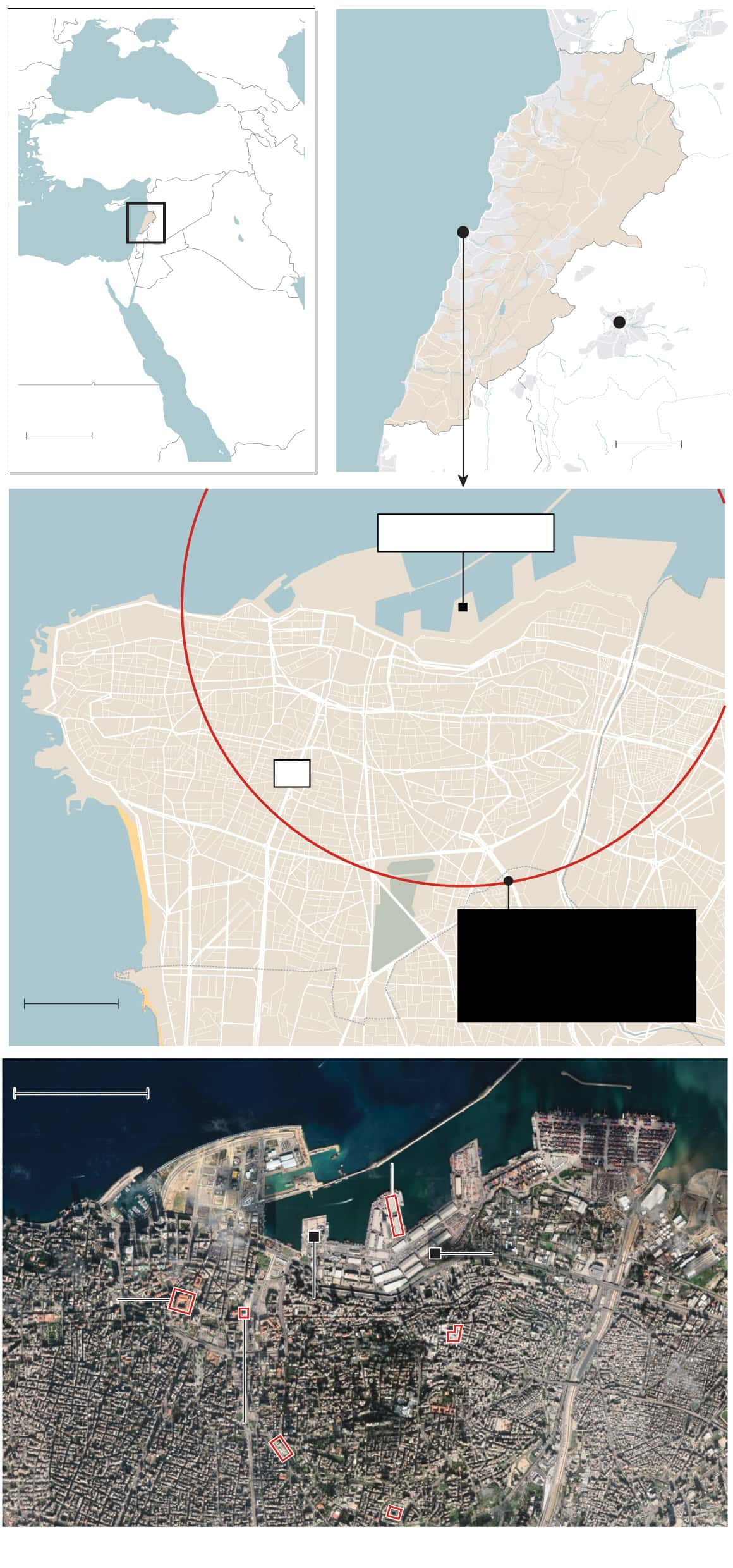

The series of events that led to Tuesday’s catastrophic explosion in Beirut appears to have begun in late 2013, when technical problems forced a cargo ship to make an unscheduled stop in the city’s port.

Lebanon’s port authorities were shocked when they boarded the vessel to inspect it. Not only was the merchant vessel Rhosus, flying a Moldovan flag, unfit to continue on its journey – it was carrying an astonishing 2,750 tons of ammonium nitrate in its hold.

That ammonium nitrate – which was eventually taken off the ship and stored in a warehouse at the port – is believed to have been responsible for Tuesday’s massive blast. Lebanon’s health ministry said Wednesday that the death toll had risen to 135 with about 5,000 wounded, according to a report from Reuters.

The death toll is expected to rise further as rescue workers continue to search through the rubble of Beirut’s devastated port district, where the explosion left little standing.

Explosion in Beirut: What we know so far about Lebanon’s disaster, and what caused it

Across the city, an estimated 250,000 people were made homeless by the disaster.

Ammonium nitrate, which is most commonly used as fertilizer, becomes explosive when it mixes with fuel oil. Videos of the Beirut explosion show a fire at a port warehouse just before the blast, which sent an orange-tinged mushroom cloud high into the sky, and caused injuries and damage across much of the densely populated Lebanese capital.

The owner of the Rhosus was a Russian national, Igor Grechushkin, whose last known address was Cyprus. He did not answer calls to his mobile phone on Wednesday. His LinkedIn page appeared to have been deleted.

Shipping records show the Rhosus began its fateful journey at the Black Sea port of Batumi, in Georgia, on Sept. 23, 2013. The intended destination for its cargo was Mozambique, but the ship only made it as far as Beirut, where it was impounded on Nov. 21, 2013.

“Upon inspection of the vessel by Port State Control, the vessel was forbidden from sailing. Most crew except the Master and four crew members were repatriated and shortly afterwards the vessel was abandoned by her owners after charterers and cargo concern lost interest in the cargo. The vessel quickly ran out of stores, bunker and provisions,” reads a note posted online by Baroudi & Associates, a Lebanese law firm that, acting on behalf of “various” unnamed creditors, obtained an order to have the ship arrested.

Lebanese Canadians suffer anxious wait for news after tragedy in Beirut

The ship’s captain (or “master”) and the four unfortunate crew members – all of them Ukrainian nationals – were forced to remain on board the Rhosus to keep the ship and its volatile cargo afloat. They became causes célebre in their native Ukraine, where local media regularly reported on the “hostages” who were trapped on board a derelict ship in the port of Beirut.

“The owner, Igor Grechushkin, actually abandoned the ship and the remaining crew,” the ship’s captain, Boris Prokoshev, said in a June 2014 statement he gave, while still aboard the Rhosus, to a Ukrainian legal aid organization. “He says that he went bankrupt. I don’t believe him, but that doesn’t matter. The fact is that he abandoned the ship and the crew, just like he abandoned his cargo, ammonium nitrate, which is on the ship.”

Finally, almost exactly a year after the ship was first detained, a Lebanese judge allowed the seamen to leave the ship and return home. “Emphasis was placed on the imminent danger the crew was facing given the ‘dangerous’ nature of the cargo still stored in ship’s holds,” reads the account by Baroudi & Associates, who said they took on the sailors’ case on compassionate grounds.

The lawyers’ note, published in a shipping industry journal called The Arrest News, which tracks ships that have been impounded, ends on an ominous note. “Owing to the risks associated with retaining the ammonium nitrate on board the vessel, the port authorities discharged the cargo onto the port’s warehouses. The vessel and cargo remain to date in port awaiting auctioning and/or proper disposal.”

Six years later, that same cargo was still in a Hangar 12 at Beirut’s port. It’s a situation that explosives experts have referred to as a “ticking time bomb.”

Lebanon’s Supreme Defense Council, which met following the blast, said the explosion appeared to have occurred during welding work at Hangar 12.

LONDON PUBLISHED AUGUST 5, 2020

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/tgam/LZN3CBALERIGDBU7UKBMAJJBBM.jpg)

A survivor is taken out of the rubble after a massive explosion in Beirut, Lebanon.

HASSAN AMMAR/THE ASSOCIATED PRESS

1 of 19 https://www.theglobeandmail.com/world/article-how-an-abandoned-ship-became-a-ticking-time-bomb-in-beirut/

The series of events that led to Tuesday’s catastrophic explosion in Beirut appears to have begun in late 2013, when technical problems forced a cargo ship to make an unscheduled stop in the city’s port.

Lebanon’s port authorities were shocked when they boarded the vessel to inspect it. Not only was the merchant vessel Rhosus, flying a Moldovan flag, unfit to continue on its journey – it was carrying an astonishing 2,750 tons of ammonium nitrate in its hold.

That ammonium nitrate – which was eventually taken off the ship and stored in a warehouse at the port – is believed to have been responsible for Tuesday’s massive blast. Lebanon’s health ministry said Wednesday that the death toll had risen to 135 with about 5,000 wounded, according to a report from Reuters.

The death toll is expected to rise further as rescue workers continue to search through the rubble of Beirut’s devastated port district, where the explosion left little standing.

Explosion in Beirut: What we know so far about Lebanon’s disaster, and what caused it

Across the city, an estimated 250,000 people were made homeless by the disaster.

Ammonium nitrate, which is most commonly used as fertilizer, becomes explosive when it mixes with fuel oil. Videos of the Beirut explosion show a fire at a port warehouse just before the blast, which sent an orange-tinged mushroom cloud high into the sky, and caused injuries and damage across much of the densely populated Lebanese capital.

The owner of the Rhosus was a Russian national, Igor Grechushkin, whose last known address was Cyprus. He did not answer calls to his mobile phone on Wednesday. His LinkedIn page appeared to have been deleted.

Shipping records show the Rhosus began its fateful journey at the Black Sea port of Batumi, in Georgia, on Sept. 23, 2013. The intended destination for its cargo was Mozambique, but the ship only made it as far as Beirut, where it was impounded on Nov. 21, 2013.

“Upon inspection of the vessel by Port State Control, the vessel was forbidden from sailing. Most crew except the Master and four crew members were repatriated and shortly afterwards the vessel was abandoned by her owners after charterers and cargo concern lost interest in the cargo. The vessel quickly ran out of stores, bunker and provisions,” reads a note posted online by Baroudi & Associates, a Lebanese law firm that, acting on behalf of “various” unnamed creditors, obtained an order to have the ship arrested.

Lebanese Canadians suffer anxious wait for news after tragedy in Beirut

The ship’s captain (or “master”) and the four unfortunate crew members – all of them Ukrainian nationals – were forced to remain on board the Rhosus to keep the ship and its volatile cargo afloat. They became causes célebre in their native Ukraine, where local media regularly reported on the “hostages” who were trapped on board a derelict ship in the port of Beirut.

“The owner, Igor Grechushkin, actually abandoned the ship and the remaining crew,” the ship’s captain, Boris Prokoshev, said in a June 2014 statement he gave, while still aboard the Rhosus, to a Ukrainian legal aid organization. “He says that he went bankrupt. I don’t believe him, but that doesn’t matter. The fact is that he abandoned the ship and the crew, just like he abandoned his cargo, ammonium nitrate, which is on the ship.”

Finally, almost exactly a year after the ship was first detained, a Lebanese judge allowed the seamen to leave the ship and return home. “Emphasis was placed on the imminent danger the crew was facing given the ‘dangerous’ nature of the cargo still stored in ship’s holds,” reads the account by Baroudi & Associates, who said they took on the sailors’ case on compassionate grounds.

The lawyers’ note, published in a shipping industry journal called The Arrest News, which tracks ships that have been impounded, ends on an ominous note. “Owing to the risks associated with retaining the ammonium nitrate on board the vessel, the port authorities discharged the cargo onto the port’s warehouses. The vessel and cargo remain to date in port awaiting auctioning and/or proper disposal.”

Six years later, that same cargo was still in a Hangar 12 at Beirut’s port. It’s a situation that explosives experts have referred to as a “ticking time bomb.”

Lebanon’s Supreme Defense Council, which met following the blast, said the explosion appeared to have occurred during welding work at Hangar 12.

No comments:

Post a Comment