Nuclear Fusion Will Not Save Us

Yessenia Funes

Wednesday August 6, 2020

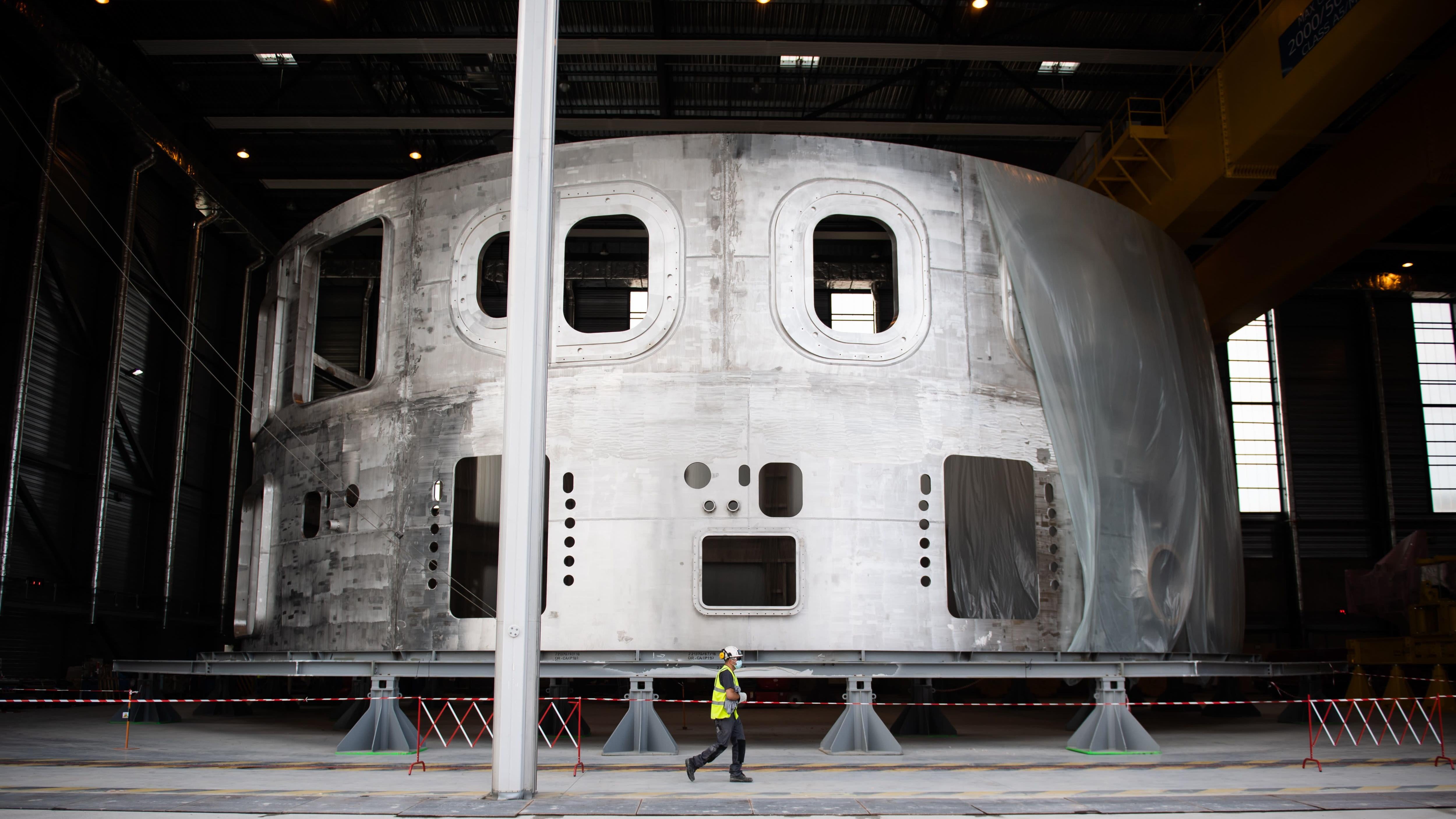

Last week, construction kicked off on the world’s largest experimental nuclear fusion reactor. It marked the start of a new era in the energy sector: The fossil fuel industry has historically dominated this arena, but renewable energy is quickly taking over. Now, nuclear scientists are hoping that the International Thermonuclear Experimental Reactor, or ITER, the experimental power plant under construction in southern France, can play a role alongside already-established technologies like solar and wind.

All the nuclear power plants that exist today rely on nuclear fission. ITER, however, will rely on nuclear fusion. The two are dramatically different, and scientists have struggled to recreate nuclear fusion—the process that makes stars shine—in a lab setting. ITER is the world’s first true attempt at this on a large scale.

The Promise and Peril of Nuclear Power

Temperatures are rising, the Antarctic is melting, and a million animal and plant species face the…Read more

“The difference between nuclear fission and nuclear fusion is the reason why we’ve developed a nuclear fission reactor in a matter of years, and still after more than six decades, we still don’t have a nuclear fusion reactor,” said Eugenio Schuster, a mechanical engineering and mechanics professor at Lehigh University who is working on ITER.

Around the world, 450 nuclear reactors were operating last year, all using nuclear fission, which involves splitting heavy atoms of elements such as uranium and plutonium. The process produces tons of highly radioactive waste, the ingredients to create nuclear weapons, potential instability that could lead to a destructive nuclear meltdown, and other concerning issues.

This process also requires uranium. In the U.S., the mining of this resource has contaminated the waters of the Navajo Nation and left countless individuals sick. President Donald Trump wants to see more uranium mining, and he doesn’t care where. The Grand Canyon? It can be mined. Bears Ears National Monument? That, too. Nuclear fission has proven destructive to both human health and the environment. There’s a reason many environmental advocates are highly opposed.

“We have a horrible legacy of uranium contamination in our communities,” said Carol Davis, the executive director of Diné C.A.R.E., an environmental organization that supports the Navajo people. “Water was contaminated with uranium, and it’s never been cleaned, and people are using that and drinking that.”

Davis and other advocates worry nuclear power is just another false promise that creates radioactive waste while taking time and money away from developing renewable energy technologies. The United States alone has 90,000 metric tons of nuclear waste with nowhere to go. Nuclear fusion doesn’t create the same level of long-lived radioactive waste as the more popular process of nuclear fission, but it isn’t waste-free, either.

The process begins with the breaking down of lighter atoms into a state of matter called plasma. It requires more than 270 million degrees Fahrenheit of heat to get going, though. When you’re comparing it to fission, of course, fusion is better. It can’t cause the nuclear meltdowns that we’ve seen at other sites. It doesn’t need any uranium; all it needs is lithium and water. If greenhouse gas emissions are the concern, fusion doesn’t have any evidence of contributing there. But the process does still produce some waste, and advocates are worried that their communities will be forced to deal with that waste for the greater good.

“This whole notion of endless power with little to no waste, it just sounds too good to be true. We really need to examine what are the true costs and who are the people who will be impacted,” said Leona Morgan, a Diné activist and coordinator of the Nuclear Issues Study Group, a New Mexico-based volunteer organization against nuclear power. “It seems like we should really learn from what we have already experienced with the loss of human rights and loss of water resources from contamination.”

If scientists want communities to fully embrace nuclear energy, they need to figure out what the hell to do with this toxic trash. In the U.S., decision-makers have historically dumped this stuff near tribal or low-income rural communities. History is bound to repeat itself if leaders don’t take proper action to prevent these injustices.

This Town Didn't Want to Be a Radioactive Waste Dump. The Government Is Giving Them No Choice.

PIKETON, OHIO—David and Pam Mills have grown tomatoes, peppers, cucumbers, and okra on their…Read more

“The reason we’re investing in fusion is because the promise is big,” Schuster said. “We’re going to have the benefits of renewables in terms of greenhouse gas emissions, but at the same time, we’re going to reduce the area we need to produce the same amount of energy while eliminating the risk of nuclear accidents and the generation of long-lived radioactive waste.”

That’s the thing, though. Intense attention on the climate crisis allows other ecological crises to happen alongside it. No one wants to see the world burn from rising temperatures, but disenfranchised communities don’t want to keep being sacrificed for the sake of human progress, either. Lithium extraction primarily happens in Argentina and Chile, where Indigenous advocates worry about the amount of water the mining requires, as well as the potential for contamination of their lands. Water is going to become even more valuable as we see droughts dry out lakes, rivers, and streams. Fusion simply doesn’t come without a cost.“This whole notion of endless power with little to no waste, it just sounds too good to be true.”

Proponents of ITER note that the amount of lithium and water needed is minimal, especially compared to the extractive industries that exist today. The plant is expected to need only 550 pounds of fuel a year, half from the isotopes they need from water and half from the isotopes they need from lithium. Schuster notes that most of the water needed for this process would be returned to its source. That’s because researchers need only a specific molecule from the water. These materials won’t be the main issue with nuclear fusion, said Egemen Kolemen, an assistant professor of mechanical and aerospace engineering at Princeton University who is also working on the plant.

“The real issue is going to be the nuclear safety issues,” Kolemen said. “Even though it doesn’t have this runaway type of [reaction], there is still going to be some sort of nuclear reactions… that are going to have low levels, but still some, nuclear waste of sorts.”

The construction of ITER certainly does mark a new chapter in the world’s energy sector. It marks a moment of technological breakthrough and scientific accomplishment, but it won’t save us by itself. No new energy source can. At the heart of the climate crisis is human behavior. If we’re to survive it—and, more importantly, solve it—we need to take a long, hard look in the mirror. Reducing emissions will require more than finding the perfect clean energy source; it will need a massive shift in human behavior, lowering our emissions through energy efficiency and less consumption.

Then again, emissions aren’t everything. If we’re lowering our carbon footprint without protecting the health of vulnerable communities, what good is it after all? A nuclear future needs a justice and equity lens if it’s to actually be successful. Otherwise, it’ll be another damaging industry. The world already has enough of those.

Yessenia Funes

PostsEmailTwitter

Yessenia Funes is a senior staff writer with Earther. She loves all things environmental justice and dreams of writing children's books.

No comments:

Post a Comment