Some crimes have seen drastic decreases during coronavirus, but not homicides in the United States

by Terry Goldsworthy, The Conversation

Credit: Shutterstock

The various restrictions put in place to combat the spread of coronavirus in recent months have disrupted life for everyone—including criminals.

More than six months into the pandemic, it is clear the pandemic has had a major effect on crime rates. Certain crimes, such as robberies and sexual offenses, have declined dramatically, while others, such as online fraud, have been on the rise.

Of course, it is difficult to firmly establish a direct causal relationship between coronavirus restrictions and crime rates, but the statistics reveal some common themes.

Reductions in burglaries and assaults

Lockdown policies in Australia and many other countries around the world have significantly altered the environment in which criminal activity can take place.

The broad view in the early days of the pandemic was some crimes would naturally decrease—those requiring access to public space, for instance, and human contact.

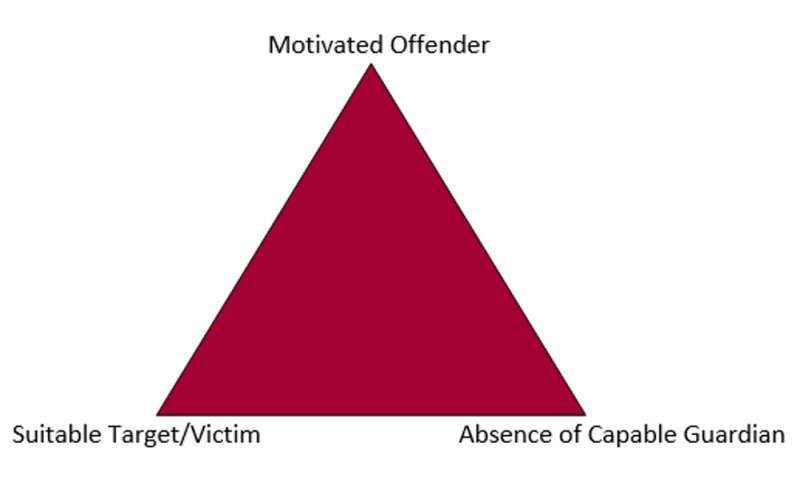

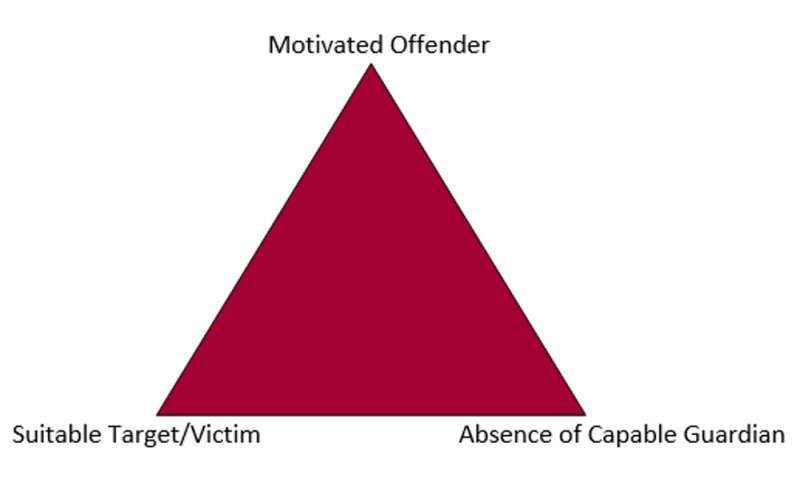

For example, under the routine activity theory in criminology, which focuses on the criteria that must be present for crimes to occur, the lockdown should have led to a significant decline in burglaries of homes. There were fewer suitable targets for burglaries (unoccupied houses) and an increase in capable guardians who could intervene (families staying at home).

The same theory can apply to violent crimes and sexual assaults—if you limit the ability of people to commit these crimes through lockdowns, it's reasonable to expect crime rates would decrease.

The statistics in Australia suggest these theories may be correct.

The NSW Bureau of Crime Statistics and Research found that in April, crime across many categories declined sharply compared to the same month for the past five years: robberies (down 42%), non-domestic assault (down 39%), sexual offenses (down 32%), break and enter of dwellings (down 29%), break and enter of non-dwellings (down 25%), stealing from motor vehicles (down 34%) and car theft (down 24%).

A similar pattern was noticeable in Queensland, comparing crime data for April to the same month in 2019—a 28% decline in unlawful entry of dwellings, 45% reduction in robberies and a 7% drop in sexual offenses.

Increases in crimes committed in private

Conversely, offenses that could be committed in private settings or remotely, such as cybercrimes, rose dramatically during the pandemic.

In Queensland, for instance, computer fraud was up 76% in April compared to the year before, while drug offenses increased by 13%.

There was also great concern that domestic violence would also increase during lockdown periods.

NSW police did not see an increase in domestic violence reports in April, compared to the previous year, and Queensland crime data shows breaches of domestic violence orders have remained stable since the start of the pandemic. The NSW Bureau of Crime Statistics and Research, however, said police could not rule out an increase in unreported domestic violence.

In contrast to this, police data for the Northern Territory showed a 25% spike in domestic violence-related assaults in parts of central Australia during the first months of the COVID-19 lockdown.

Routine activity theory (or the crime triangle). Credit: UN Office on Drugs and Crime

Routine activity theory (or the crime triangle). Credit: UN Office on Drugs and Crime

A study by the Australian Institute of Criminology (AIC) surveyed 15,000 Australian women to gage the prevalence of domestic violence during the lockdown period from February to May. It found 4.6% of women experienced physical or sexual violence from a partner and 11.6% reported experiencing emotionally abusive, harassing or controlling behavior.

The report noted more research was needed to understand the problem.

"Given the majority of women experiencing violence and abuse within their relationships do not engage with police or government or non-government agencies—particularly while they remain in a relationship with their abuser—this is a significant gap in knowledge."

Crime also down overseas, but homicides on the rise

Other countries reported similar decreases in crime. In England and Wales, crime dropped consistently by an average of 24% per month over a three-month period from April to June compared to the same period for 2019.

These figures, however, did not include fraud offenses, which increased during the pandemic. In March, reported frauds in the UK increased by 400%.

Scotland also saw an 18% decrease in overall crime in April compared to the same month in 2019. One of the few exceptions to this was a 38% rise in fraud.

In the US, however, the findings have been mixed. One study that looked at crime in 16 large cities from January to May (when lockdowns were coming into force) found reductions in residential burglaries and car thefts in some cities, but little to no change to non-residential burglaries and serious assaults (including homicides).

Another study looking at the effect of social distancing on crime in two cities, Los Angeles and Indianapolis, found it "had a statistically significant impact on a few specific crime types. However, the overall effect is notably less than might be expected given the scale of the disruption to social and economic life."

Finally, a major study by the University of Pennsylvania found overall crime across 25 cities in the US declined by 23% in the first month of the pandemic, compared to the average over five years of data for the same time period.

Notably, the study found crime declined even before stay-at-home orders were issued as people changed their normal routines and spent more time at home. Drug crimes saw the biggest decline of any crime category, while home burglaries, assaults and robberies were also down across the 25 cities.

However, the study found little change to homicide rates or shootings in the first month after stay-at-home orders. One possible reason for this, the authors note, is people committing these types of crime are unlikely to be concerned with stay-at-home orders.

In a separate analysis of crime data conducted by The New York Times, murders were up 21.8% in the 36 US cities it studied through at least May, compared to data for the same time period last year.

Other academics have said it is difficult to draw conclusions on homicide rates during the pandemic due to a lack of long-term data.

Further study of the impact of COVID-19 on crime will be required. In the UK, Leeds University has just been awarded funding to conduct such a study over the next 18 months.

Future challenges

Not only will law enforcement be required to adapt to the effect of COVID-19 responses on criminal behavior, the role of law enforcement is also being expanded to take on non-traditional roles in the pandemic.

And the full economic impact of the pandemic has yet to be seen. Many economies have been insulated to some degree by government assistance programs, but the extent to which a severe economic downturn could affect crime rates is still not known.

Explore furtherStudy shows domestic violence reports on the rise as COVID-19 keeps people at home

Provided by The Conversation

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

6 shares

The various restrictions put in place to combat the spread of coronavirus in recent months have disrupted life for everyone—including criminals.

More than six months into the pandemic, it is clear the pandemic has had a major effect on crime rates. Certain crimes, such as robberies and sexual offenses, have declined dramatically, while others, such as online fraud, have been on the rise.

Of course, it is difficult to firmly establish a direct causal relationship between coronavirus restrictions and crime rates, but the statistics reveal some common themes.

Reductions in burglaries and assaults

Lockdown policies in Australia and many other countries around the world have significantly altered the environment in which criminal activity can take place.

The broad view in the early days of the pandemic was some crimes would naturally decrease—those requiring access to public space, for instance, and human contact.

For example, under the routine activity theory in criminology, which focuses on the criteria that must be present for crimes to occur, the lockdown should have led to a significant decline in burglaries of homes. There were fewer suitable targets for burglaries (unoccupied houses) and an increase in capable guardians who could intervene (families staying at home).

The same theory can apply to violent crimes and sexual assaults—if you limit the ability of people to commit these crimes through lockdowns, it's reasonable to expect crime rates would decrease.

The statistics in Australia suggest these theories may be correct.

The NSW Bureau of Crime Statistics and Research found that in April, crime across many categories declined sharply compared to the same month for the past five years: robberies (down 42%), non-domestic assault (down 39%), sexual offenses (down 32%), break and enter of dwellings (down 29%), break and enter of non-dwellings (down 25%), stealing from motor vehicles (down 34%) and car theft (down 24%).

A similar pattern was noticeable in Queensland, comparing crime data for April to the same month in 2019—a 28% decline in unlawful entry of dwellings, 45% reduction in robberies and a 7% drop in sexual offenses.

Increases in crimes committed in private

Conversely, offenses that could be committed in private settings or remotely, such as cybercrimes, rose dramatically during the pandemic.

In Queensland, for instance, computer fraud was up 76% in April compared to the year before, while drug offenses increased by 13%.

There was also great concern that domestic violence would also increase during lockdown periods.

NSW police did not see an increase in domestic violence reports in April, compared to the previous year, and Queensland crime data shows breaches of domestic violence orders have remained stable since the start of the pandemic. The NSW Bureau of Crime Statistics and Research, however, said police could not rule out an increase in unreported domestic violence.

In contrast to this, police data for the Northern Territory showed a 25% spike in domestic violence-related assaults in parts of central Australia during the first months of the COVID-19 lockdown.

Routine activity theory (or the crime triangle). Credit: UN Office on Drugs and Crime

Routine activity theory (or the crime triangle). Credit: UN Office on Drugs and CrimeA study by the Australian Institute of Criminology (AIC) surveyed 15,000 Australian women to gage the prevalence of domestic violence during the lockdown period from February to May. It found 4.6% of women experienced physical or sexual violence from a partner and 11.6% reported experiencing emotionally abusive, harassing or controlling behavior.

The report noted more research was needed to understand the problem.

"Given the majority of women experiencing violence and abuse within their relationships do not engage with police or government or non-government agencies—particularly while they remain in a relationship with their abuser—this is a significant gap in knowledge."

Crime also down overseas, but homicides on the rise

Other countries reported similar decreases in crime. In England and Wales, crime dropped consistently by an average of 24% per month over a three-month period from April to June compared to the same period for 2019.

These figures, however, did not include fraud offenses, which increased during the pandemic. In March, reported frauds in the UK increased by 400%.

Scotland also saw an 18% decrease in overall crime in April compared to the same month in 2019. One of the few exceptions to this was a 38% rise in fraud.

In the US, however, the findings have been mixed. One study that looked at crime in 16 large cities from January to May (when lockdowns were coming into force) found reductions in residential burglaries and car thefts in some cities, but little to no change to non-residential burglaries and serious assaults (including homicides).

Another study looking at the effect of social distancing on crime in two cities, Los Angeles and Indianapolis, found it "had a statistically significant impact on a few specific crime types. However, the overall effect is notably less than might be expected given the scale of the disruption to social and economic life."

Finally, a major study by the University of Pennsylvania found overall crime across 25 cities in the US declined by 23% in the first month of the pandemic, compared to the average over five years of data for the same time period.

Notably, the study found crime declined even before stay-at-home orders were issued as people changed their normal routines and spent more time at home. Drug crimes saw the biggest decline of any crime category, while home burglaries, assaults and robberies were also down across the 25 cities.

However, the study found little change to homicide rates or shootings in the first month after stay-at-home orders. One possible reason for this, the authors note, is people committing these types of crime are unlikely to be concerned with stay-at-home orders.

In a separate analysis of crime data conducted by The New York Times, murders were up 21.8% in the 36 US cities it studied through at least May, compared to data for the same time period last year.

Other academics have said it is difficult to draw conclusions on homicide rates during the pandemic due to a lack of long-term data.

Further study of the impact of COVID-19 on crime will be required. In the UK, Leeds University has just been awarded funding to conduct such a study over the next 18 months.

Future challenges

Not only will law enforcement be required to adapt to the effect of COVID-19 responses on criminal behavior, the role of law enforcement is also being expanded to take on non-traditional roles in the pandemic.

And the full economic impact of the pandemic has yet to be seen. Many economies have been insulated to some degree by government assistance programs, but the extent to which a severe economic downturn could affect crime rates is still not known.

Explore furtherStudy shows domestic violence reports on the rise as COVID-19 keeps people at home

Provided by The Conversation

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

6 shares

No comments:

Post a Comment