STONEHENGE’S UNREAL, REAL LIFE ACOUSTICS WOULD HAVE IMPRESSED THE GUYS OF SPINAL TAP

Credit: MGM

Contributed by

Sep 9, 2020,

Maybe the model of Stonehenge that materialized in the haze of a fog machine onstage in This is Spinal Tap was just a piece of spray-painted Styrofoam that almost got crushed, but a similar model has revealed the Neolithic monument probably had much better acoustics than that theater the band was playing.

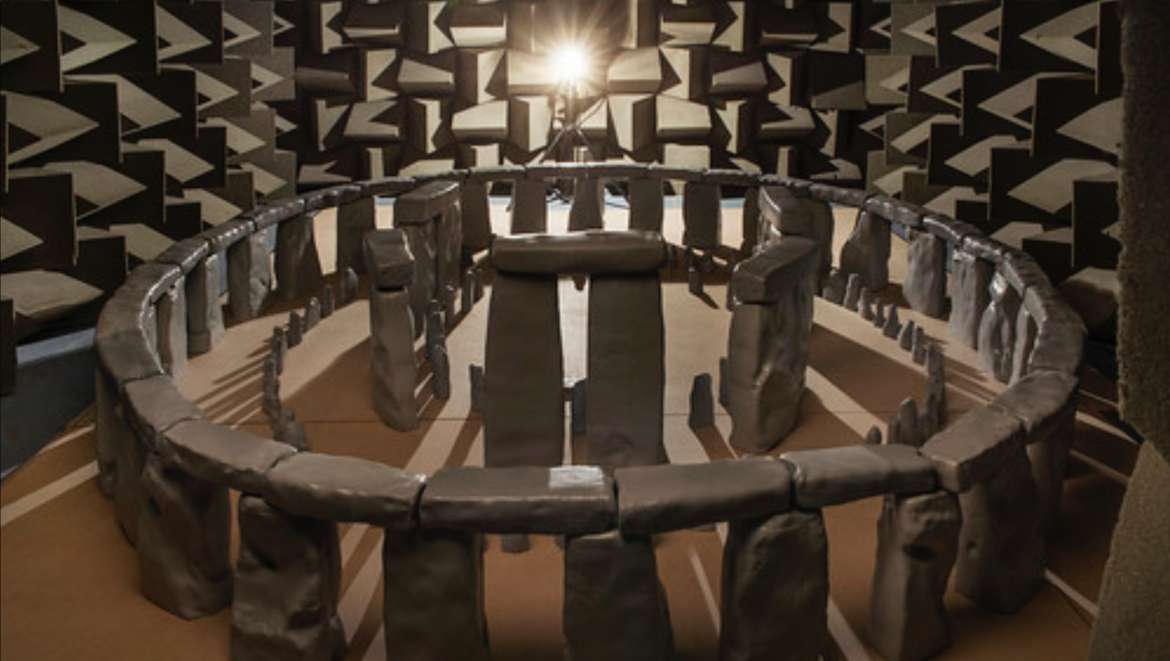

Stonehenge might have not actually been an arena to watch guys in hooded robes and glitter eyeshadow act all otherworldly, but it did have killer acoustics. At least the way it was recently found to have been configured to amplify sound but still keep it inside defies the notion that no one knew how to achieve special effects during the Stone Age. University of Salford professor Trevor Cox and his research team worked backwards — instead of building a scale model of a future concert hall, they used the prehistoric gathering place to create such a model. The Spinal Tap-size Stonehenge they created could literally speak (or sing) of its secrets.

“Getting the size, shape and location of the stones right is the most important aspect,” Cox, who led a study recently published in Journal of Arachaeological Science, told SYFY WIRE. “To do that we used a computer reconstruction from Historic England that follows the best current archaeological evidence. The stones themselves were made hard and impervious so sound readily reflected off them as happens with stones.”

Credit: Trevor Cox

There were no such things as mics and amps 5,000 years ago. People who had something to say to others, or to their gods, needed to be in a place that was made for their voices to be heard. The reverse building of Stonehenge needed sound frequencies to be 12 times what they were estimated to have been in the original monument. While the actual rituals that took place at Stonehenge can only be guessed at, the way it is constructed to let light in at a particular angle during the the winter and summer solstice suggests ancient Pagan ceremonies. This could be why it was constructed to keep intonations or music inside the scared circle.

To create what could pass as a much more accurate Spinal Tap prop, Cox and his team 3D-printed versions of the 27 types of megalithic stones found at Stonehenge. They then used these replicas to make molds and cast enough to create a scaled-down version of what was once a 157-stone monument. The replicas were filled various materials meant to come as close as possible to the texture and density of the actual stones. Only 63 complete and 12 fragmented stones exist today, and most have suffered from erosion and other ravages of time. However, Cox was careful to note that despite his findings on the acoustics at Stonehenge, sound was only a secondary consideration in how Stonehenge was built.

Credit: Trevor Cox

“I doubt that they built Stonehenge for the sound,” he said. “other considerations like astronomical alignments are much more likely to have determined the construction. More likely they built it, and then found it helped enhance speech and musical sounds, which then could have influenced how they used the site."

Since its construction, Stonehenge is obviously not as it used to be. Missing stones and the wear of thousands of years has affected how sound is heard within. Stone reflections create the reverberation that amplifies sound. An incomplete monument means that there are not as many stones to give an accurate representation of what that reflection must have once sounded like. Surprisingly, the recreation showed that the original was lacking in echoes that had been hypothesized before. Reflections were obscured and scattered by the inner sanctum of bluestones and trilithons, or structures consisting of two upright sarsen stones with a third lying horizontally across them. The stones were rearranged several times during the Neolithic age, but Cox argues the acoustic changes resulting from this were inaudible.

The scale model revealed that most sounds made within Stonehenge were probably not heard well by outsiders, and the same goes for sounds occurring outside the circle, which must have not been heard well by anyone on the inside. Whether it was the builders’ intention to keep sacred incantations from escaping hallowed ground, or to prevent outside noise from interfering with rituals — or both — remains unknown.

"When we get together for a ceremony we make sounds: speaking, singing or playing music," Cox said. "It is reasonable to assume similar sounds were being made in Stonehenge in prehistory. What our results show is that the amplification of sound via stone reflections happens only within the stone circles, and sound does not readily pass from inside to outside the circle. Consequently, if you're holding a ceremony there, it works best if everyone is inside the circle."

More may be demystified in the future, but some things that emerge from shadows of the past may forever keep their mystery.

No comments:

Post a Comment